Estate Fraud and Spurious Pedigrees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDWARDS Family.Pdf

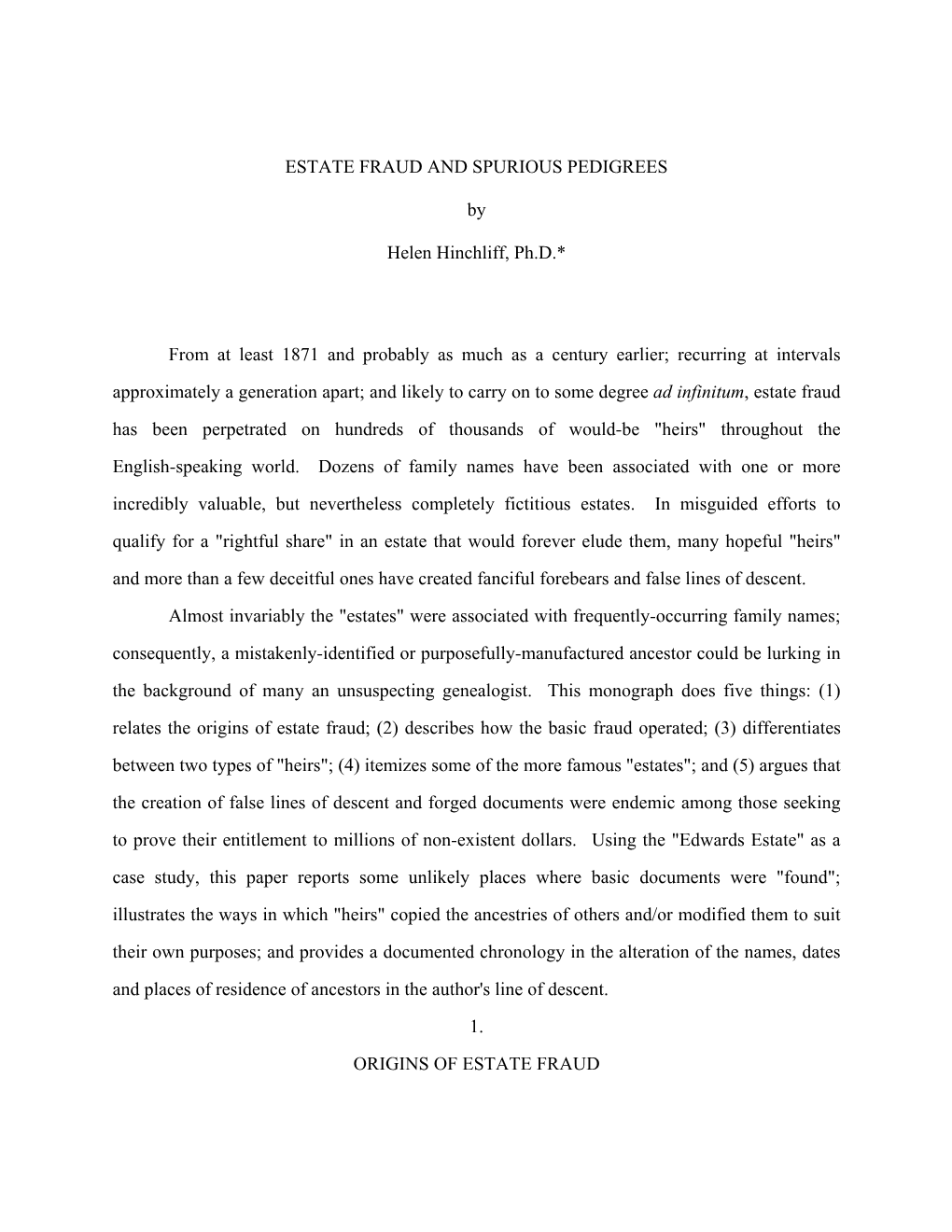

,_~(J ~ '\h~ NJ.""~\ L\,,~ \ vJ.J~ ~i.A~~t 't ?"d_,_J £°"-'\<~ I )\,J\ la<-.J.,c~ 1\).,,,..,1, .... : Xe 5 4-44 E 2G e...2-G. cc~ - -+~6 QCr.~c ~g:cccn:Mt"S:: '°' , The Edwardes Legacy by David D. Edwards ~GATEWAY PRESS, INC. L...::~=-"'-~.=;..._; BALTIMORE 1992 -~o- 1 1 THE MIRROR, TueJday, September 28, 1999 PAGE 15 PIRATE'S HEIRS TO ATAKEMERICA may turn into MANHATTANa when he wa.s about to be sac.ki?d for By ANNE1TE W11HERJDGE modern-day treastre island for cruising Broadway 1n drag. of Edwards Heirs - with 3.200 Trinity Church lawyers · argue more than 5,000 descendants members in America and 2.000 in they know nothing of Edwards. of a 17th century Welsh pirate. Wales - are set to grab 78 prime But after years of delay, a feder They have been given the go acres worth S680billion. al court in Pittsburgh, Pemisylva. aheact. to claim a ch unk of Man The Edwards clan say Queen nia. says there is a claim because hatta.ri worth billions of pounds. Anne gave him 100 acres for raid records show that the pirate owned The relatives of swashbuckling ing treasure-laden Spanish galleons. land in New York in the 1690s. Robert Edwards have battled New Edwards leased lower Manhattan Family spokeswoman Cleoma York's Trinity Church through the to Trinity and the heirs say the Foore said: "This will be our best courts for years. church wardens had to hand it back bite at the Big Apple." ;_ A judge ha.s ruled that the group after 99 years. -

Hamlet (The New Cambridge Shakespeare, Philip Edwards Ed., 2E, 2003)

Hamlet Prince of Denmark Edited by Philip Edwards An international team of scholars offers: . modernized, easily accessible texts • ample commentary and introductions . attention to the theatrical qualities of each play and its stage history . informative illustrations Hamlet Philip Edwards aims to bring the reader, playgoer and director of Hamlet into the closest possible contact with Shakespeare's most famous and most perplexing play. He concentrates on essentials, dealing succinctly with the huge volume of commentary and controversy which the play has provoked and offering a way forward which enables us once again to recognise its full tragic energy. The introduction and commentary reveal an author with a lively awareness of the importance of perceiving the play as a theatrical document, one which comes to life, which is completed only in performance.' Review of English Studies For this updated edition, Robert Hapgood Cover design by Paul Oldman, based has added a new section on prevailing on a draining by David Hockney, critical and performance approaches to reproduced by permission of tlie Hamlet. He discusses recent film and stage performances, actors of the Hamlet role as well as directors of the play; his account of new scholarship stresses the role of remembering and forgetting in the play, and the impact of feminist and performance studies. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS www.cambridge.org THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons, University of Munster ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. -

Publishing Spring 2021

Publishing Spring 2021 It is with great excitement that Royal Museums Greenwich announces the list of publications planned for spring 2021. The list of books presented in this catalogue showcase world-leading expertise, fascinating stories and beautiful artworks inspired by the sea, ships, time and the stars. Every purchase supports the Museum to help fund research, exhibitions and acquisitions. We hope you enjoy reading them as much as we’ve enjoyed producing them. Royal Museums Greenwich Publishing team New titles Stars Planets Pirates Royal Observatory Greenwich Royal Observatory Greenwich Fact and Fiction Illuminates series Illuminates series David Cordingly and John Falconer Dr Greg Brown Dr Emily Drabek-Maunder The image of the pirate is one There are approximately ten-billion- Since ancient times five planets that has never failed to capture trillion stars in the entire observable have been easily visible to the the imagination, but behind the Universe. That’s a little more than naked eye - Mercury, Venus, Mars, melodramatic portrayals of such the number of grains of sand on Jupiter and Saturn. This second villains as Long John Silver lies a all the beaches on Earth. But what book in the Royal Observatory much harsher reality. This book exactly are stars? How long do they Greenwich Illuminates series charts showcases the National Maritime live? How hot are they? The answers humanity’s understanding of our Museum’s vast collection of to these questions and many more neighbouring bodies, from the first artworks and artefacts, charting are answered in the first book in clues established by Galileo Galilei the history of piracy, the popular a series of accessible guides to in the 17th century, through to the portrayal of pirates in literature astronomy, written by astronomers vast amount we do (and much we and cinema, as well as examining at the Royal Observatory Greenwich. -

Tobacco and Its Role in the Life of the Confederacy D

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Spring 1993 Tobacco and Its Role in the Life of the Confederacy D. T. Smith Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Economic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, D. T.. "Tobacco and Its Role in the Life of the Confederacy" (1993). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/25rf-3v69 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/30 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOBACCO AND ITS ROLE IN THE LIFE OF THE CONFEDERACY by D . T . Smith B.A. May 1981, University of Akron, Akron, Ohio A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May, 1993 Approved by: Harbld S. Wilson (Director) Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Copyright by David Trent Smith © 1993 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT TOBACCO AND ITS ROLE IN THE LIFE OF THE CONFEDERACY D . T . Smith Old Dominion University, 1993 Director: Dr. Harold S. Wilson This study examines the role that tobacco played in influencing Confederate policy during the American Civil War. -

Free Trade & Family Values: Kinship Networks and the Culture of Early

Free Trade & Family Values: Kinship Networks and the Culture of Early American Capitalism Rachel Tamar Van Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Rachel Tamar Van All Rights Reserved. ABSTRACT Free Trade & Family Values: Kinship Networks and the Culture of Early American Capitalism Rachel Tamar Van This study examines the international flow of ideas and goods in eighteenth and nineteenth century New England port towns through the experience of a Boston-based commercial network. It traces the evolution of the commercial network established by the intertwined Perkins, Forbes, and Sturgis families of Boston from its foundations in the Atlantic fur trade in the 1740s to the crises of succession in the early 1840s. The allied Perkins firms and families established one of the most successful American trading networks of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and as such it provides fertile ground for investigating mercantile strategies in early America. An analysis of the Perkins family’s commercial network yields three core insights. First, the Perkinses illuminate the ways in which American mercantile strategies shaped global capitalism. The strategies and practices of American merchants and mariners contributed to a growing international critique of mercantilist principles and chartered trading monopolies. While the Perkinses did not consider themselves “free traders,” British observers did. Their penchant for smuggling and seeking out niches of trade created by competing mercantilist trading companies meant that to critics of British mercantilist policies, American merchants had an unfair advantage that only the liberalization of trade policy could rectify. -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade to America, Vol 1

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A. Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXVIII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698--1729 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698-1729 EDITED BY DAVID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1986 ISBN 0 901583 00 00 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction vii Note on transcription xxix List of Abbreviations xxix Text 1 Index 193 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of compiling and editing the information on Bristol trading voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have been fortunate to receive assistance and encouragement from a number of groups and individuals. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice given to me by the staffs of the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Mer chant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to use material from them. My thanks are due also to the British Academy for its generosity in providing me with a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. Finally I am indebted to Miss Mary Williams, the City Archivist in Bristol, and Professor Patrick McGrath, the General Editor of the Bristol Record Society, for their warm response to my initial proposal for this volume and for their guidance and help in bringing it to fruition. -

Links in the Chain: British Slavery, Victoria and South Australia

BEFORE / NOW Vol. 1 No. 1 Links in the Chain: British slavery, Victoria and South Australia By C. J. Coventry KEYWORDS Abstract Slavery; compensation; Beneficiaries of British slavery were present in colonial Victoria and provincial South British West Indies; colonial Victoria; provincial South Australia, a link overlooked by successive generations of historians. The Legacies of Australia; Legacies of British British-slave Ownership database, hosted by University College, London, reveals many Slave-ownership; people in these colonies as having been connected to slave money awarded as compensation place-names. by the Imperial Parliament in the 1830s. This article sets out the beneficiaries to demonstrate the scope of exposure of the colonies to slavery. The list includes governors, jurists, politicians, clergy, writers, graziers and financiers, as well as various instrumental founders of South Australia. While Victoria is likely to have received more of this capital than South Australia, the historical significance of compensation is greater for the latter because capital from beneficiaries of slavery, particularly George Fife Angas and Raikes Currie, ensured its creation. Evidence of beneficiaries of slavery surrounds us in the present in various public honours and notable buildings. Introduction Until recently slavery in Australia was thought to be associated only with the history of Queensland and the practice of ‘blackbirding’. However, the work undertaken by the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership at the University College, London, demonstrates the importance of slavery to the British Empire more generally. The UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-ownership database catalogues the people who sought compensation from the Imperial Parliament for slaves emancipated in the 1830s, in recognition of their loss of property. -

Spring 2021 Unicorn Publishing Group

UNICORN PUBLISHING GROUP SPRING 2021 Welcome to Unicorn Publishing Group’s Spring 2021 catalogue Contents Launched virtually, rather than on our usual stand at the Frankfurt Book Fair, this year’s Spring 2021 catalogue represents not only our nest collection of new titles ever, UK Office Forthcoming Titles but a bold statement of condence in the future of high quality publishing in general 5 Newburgh Street 2 Unicorn and the Unicorn Publishing Group imprints in particular. London W1F 7RG 37 Uniform 40 Universe Six months ago, the cancelled London Book Fair and the subsequent general lockdown UK Design Office 41 Unify presented every business with an existential challenge to survive. We decided to ght Charleston Studio, Client Publisher Titles our way through Covid, keeping the studio open all the time, not furloughing any sta, Meadow Business Centre 42 Notting Hill Editions keeping to our existing marketing commitments and redoubling our eorts to acquire Lewes BN8 5RW 44 Royal Museums Greenwich exciting new titles. e results can be seen in the pages of this catalogue, all acquired Tel: +44 (0)1273 812 066 50 Imperial War Museum during the Covid lockdown. Web: www.unicornpublishing.org 54 e Historic New Orleans Collection 56 Royal Armouries Our visual arts and cultural history imprint Unicorn leads with e Heart of the Rights 57 Unicorn Press Renaissance: Stories of the Art of Florence by Richard Lloyd; John Hassall: e Life and Print Company Verlagsgesellscha m.b.H. Art of the Poster King by Lucinda Gosling; Beauty in Letters: A Selection -

A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803

A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803 by Martha W. McCartney with contributions by Lorena S. Walsh data collection provided by Ywone Edwards-Ingram Andrew J. Butts Beresford Callum National Park Service | Colonial Williamsburg Foundation A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803 by Martha W. McCartney with contributions by Lorena S. Walsh data collection provided by Ywone Edwards-Ingram Andrew J. Butts Beresford Callum Prepared for: Colonial National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cooperative Agreement CA-4000-2-1017 Prepared by: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Marley R. Brown III Principal Investigator Williamsburg, Virginia 2003 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................................................iii Notes on Geographical and Architectural Conventions ..................................................................... v Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2. Research Design ............................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 3. Assessment of Contemporary Literature, BY LORENA S. WALSH .................................................... 5 Chapter 4. Evolution and Change: A Chronological Discussion ...................................................... -

Genealogical Works of Robert M Willis Volume IV

Genealogical Works of Robert M Willis Volume IV Typed for The Lawrence Register website by Oma Griffith RECEIVED: 8/23/71 FROM: Mrs Elizabeth Burwell Manship 59 Fair Crest Rd. Ashville, NC 28804 Wharton, Texas March 17, 1951 Mrs Jas S Beasley Royal Cake Nashville 5, Tennessee Dear Mrs Beasley: Your address was sent to me by Mrs Jackson of Amarillo, with whom I have had correspondence regarding the EDWARDS Family. It seems many of us are descendants of the illustrious EDWARDS Family, but as their descendants are legion, it is a problem to stay on the right line. I have accumulated much EDWARDS data in my search and occasionally have the thrill of passing some on which ties in and helps someone else or put people in touch with each other who are searching the same line, as research is one of my hobbies. Many people have helped me too on my numerous families, for which I am very grateful. Mrs Jacksons and my lines are not the same. Your line and my line could be. Here is my line and if it ties in with yours along the way won’t you please let me hear from you. I go back through a paternal grandmother- Henrietta Randolph M Edwards m Willis McLendon in Talbot Co, GA, 1849. Henrietta the daughter of WILLLIAM POSEY EDWARDS and Winnifred Ann Blow m 1825 in Jones Co, Ga. William Posey Edwaras the only living son of Thomas Lawson Edwards and Mary Heath, m 1798 either in Tenn. or GA and died in Hancock, GA in 1821. -

CIVIL ENGINEERS LICENSES ISSUED PRIOR to 1/1/82 (Numerically Arranged)

CIVIL ENGINEERS LICENSES ISSUED PRIOR TO 1/1/82 (Numerically Arranged) The following list includes licenses issued up to 33,965. As of 1/1/82, civil engineers may practice engineering surveying only. 1 Givan, Albert 80 Volk, Kenneth Quinton 159 Rossen, Merwin 238 Fogel, Swen H. 2 Baker, Donald M. 81 Talbot, Frank D. 160 Hill, Raymond A. 239 Getaque, Harry A. 3 Brunnier, H. J. 82 Blaney, Harry F. 161 Allin, T. D. 240 Welch, Edward E. 4 Bryan, Everett N. 83 Thomas, Franklin 162 Wirth, Ralph J. 241 Ronneburg, Trygve 5 Calahan, Pecos H. 84 Mau, Carl Frederick 163 Plant, Francis B. 242 Hawley, Ralph S. 6 Collins, James F. 85 Taplin, Robert Baird 164 Bates, Francis 243 Gates, Leroy G. 7 Hyatt, Edward 86 Proctor, Asa G. 165 Chalmers, William 244 Phillips, A. W. 8 Hogoboom, William C. 87 Gerdine, Thos. G. 166 Adams, Charles Robert 245 Krafft, Alfred J. 9 Muhs, Frederick Ross 88 Hackley, Robert E. 167 Bonebrake, C. C. 246 Meikle, R. V. 10 Grumm, Fred J. 89 Camp, W. E. 168 Roberts, Joseph Emmet 247 Davies, Donald, Jr. 11 Wirsching, Carl B. 90 Dennis, T. H. 169 Wylie, Paul E. 248 Murray, M. M. 12 Leonard, Jno. B. 91 Clarke, William D. 170 Tripp, J. G. 249 Doolan, Jerome K. 13 Schenck, Harry A. 92 Murray, Warren E. 171 Hasbrouck, Philip B. 250 Salsbury, Markham E. 14 Marx, Charles David 93 Holfelder, Joseph B. 172 Reaburn, DeWitt L. 251 Joyner, Frank Hal 15 Grunsky, Carl Ewald 94 Conway, Clarence D. 173 Wade, Clifford L. -

‗The Dignity of Labor': African-American

‗THE DIGNITY OF LABOR‘: AFRICAN-AMERICAN CONNECTIONS TO THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT, 1868-1915 Elaine Fussell Pinson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2012 ©2012 Elaine Fussell Pinson All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iv PREFACE ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE: 8 ‗The Dignity of Labor‘: Work and Social Reform CHAPTER TWO: 26 ‗Training, Head, Hand, and Heart‘: African-American Industrial Education CHAPTER THREE: 56 Exposure and Influence: African-American Industrial Education Beyond School Walls CHAPTER FOUR: 82 ‗Working with the Hands‘: Objects and the Built Environment at Tuskegee Institute CONCLUSION 97 NOTES 101 BIBLIOGRAPHY 118 ILLUSTRATIONS 129 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people encouraged, assisted, and supported me in all stages of this project. I offer my sincere thanks and appreciation to Cynthia Williams, director and assistant professor, Smithsonian-Mason MA in the History of Decorative Arts for her continued support and understanding. My thesis advisor and first professor at HDA, Heidi Nasstrom Evans, Ph.D, professor of George Mason University, provided encouragement and insightful and diplomatic critiques. My thesis would not have come to fruition without her. Dr. Eileen Boris, Hull Professor and Chair, University of California, Santa Barbara, read and provided incisive comments on my thesis draft. Professor Dorothea Dietrich provided constructive feedback during the thesis proposal process. And thanks to my professors and colleagues in the HDA Program who felt my ―pain‖ and lessened it with their kindness and commiseration.