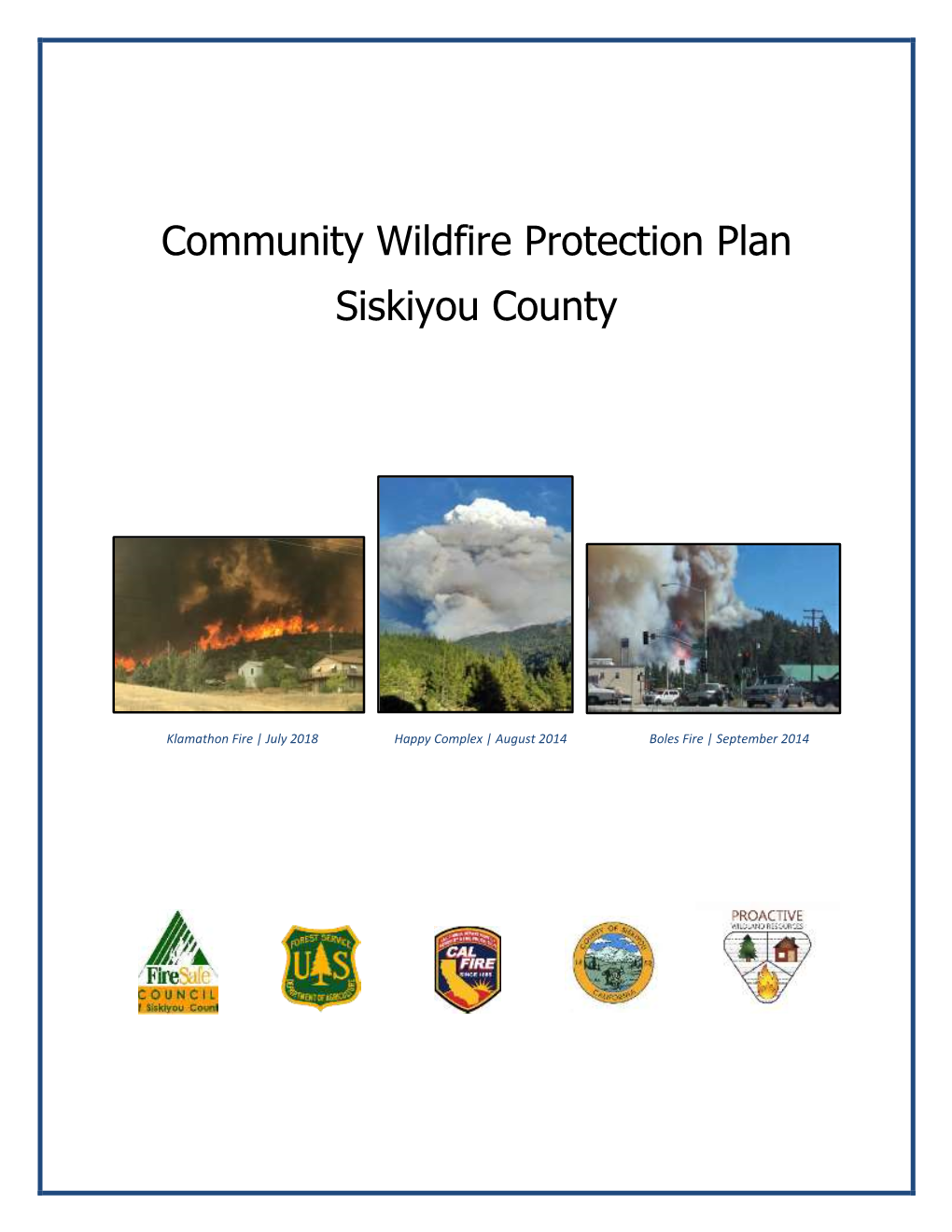

Community Wildfire Protection Plan Siskiyou County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weld County 2011-2013 Annual Wildfire Operating Plan

WELD COUNTY 2011-2013 ANNUAL WILDFIRE OPERATING PLAN Prepared by: Weld County Office of Emergency Management Weld County Fire Chiefs’ Association Colorado State Forest Service, Fort Collins District Pawnee National Grasslands, Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forests This agreement is to remain in effect until the next Annual Operating Plan is modified and signed TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ANNUAL WILDFIRE OPERATING PLAN APPROVALS ............................................. 3 II. JURISDICTIONS / MAP ..................................................................................................... 4 III. AUTHORITIES FOR THIS PLAN ..................................................................................... 4 IV. PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................ 4 V. FIRE MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................................... 4 VI. RESOURCE LIST ............................................................................................................... 4 VII. WILDFIRE READINESS .................................................................................................... 5 A. Planning ................................................................................................................................ 5 B. Training ................................................................................................................................. 5 C. Equipment ........................................................................................................................... -

Fire and Nonnative Invasive Plants September 2008 Zouhar, Kristin; Smith, Jane Kapler; Sutherland, Steve; Brooks, Matthew L

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Ecosystems General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 6 Fire and Nonnative Invasive Plants September 2008 Zouhar, Kristin; Smith, Jane Kapler; Sutherland, Steve; Brooks, Matthew L. 2008. Wildland fire in ecosystems: fire and nonnative invasive plants. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 6. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 355 p. Abstract—This state-of-knowledge review of information on relationships between wildland fire and nonnative invasive plants can assist fire managers and other land managers concerned with prevention, detection, and eradi- cation or control of nonnative invasive plants. The 16 chapters in this volume synthesize ecological and botanical principles regarding relationships between wildland fire and nonnative invasive plants, identify the nonnative invasive species currently of greatest concern in major bioregions of the United States, and describe emerging fire-invasive issues in each bioregion and throughout the nation. This volume can help increase understanding of plant invasions and fire and can be used in fire management and ecosystem-based management planning. The volume’s first part summarizes fundamental concepts regarding fire effects on invasions by nonnative plants, effects of plant invasions on fuels and fire regimes, and use of fire to control plant invasions. The second part identifies the nonnative invasive species of greatest concern and synthesizes information on the three topics covered in part one for nonnative inva- sives in seven major bioregions of the United States: Northeast, Southeast, Central, Interior West, Southwest Coastal, Northwest Coastal (including Alaska), and Hawaiian Islands. -

Fire Management.Indd

Fire today ManagementVolume 65 • No. 2 • Spring 2005 LLARGEARGE FFIRESIRES OFOF 2002—P2002—PARTART 22 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Erratum In Fire Management Today volume 64(4), the article "A New Tool for Mopup and Other Fire Management Tasks" by Bill Gray shows incorrect telephone and fax numbers on page 47. The correct numbers are 210-614-4080 (tel.) and 210-614-0347 (fax). Fire Management Today is published by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication of this periodical is necessary in the transaction of the pub- lic business required by law of this Department. Fire Management Today is for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, at: Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: 202-512-1800 Fax: 202-512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 Fire Management Today is available on the World Wide Web at http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/fmt/index.html Mike Johanns, Secretary Melissa Frey U.S. Department of Agriculture General Manager Dale Bosworth, Chief Robert H. “Hutch” Brown, Ph.D. Forest Service Managing Editor Tom Harbour, Director Madelyn Dillon Fire and Aviation Management Editor Delvin R. Bunton Issue Coordinator The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communica- tion of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TDD). -

Table 10 Papers Not Responding to the ASNE Survey Ranked by Circulation

Table 10 Papers not responding to the ASNE survey Ranked by circulation (DNR = did not report to ASNE last year, too.) Source: Report to the Knight Foundation, May 2004 by Bill Dedman and Stephen K. Doig. The full report is at http://www.asu.edu/cronkite/asne Rank Newspaper, State Weekday Ownership Circulation Staff non-white % circulation area non- for previous year white % (year-end 2002), if paper responded 1 New York Post, New York 652,426 40.3 DNR 2 Chicago Sun-Times, Illinois 481,798 Hollinger International 50.3 DNR (Ill.) 3 The Star-Ledger, Newark, New Jersey 408,672 Advance (Newhouse) 36.8 16.5 (N.Y.) 4 The Columbus Dispatch, Ohio 252,564 17.3 DNR 5 Boston Herald, Massachusetts 241,457 Herald Media (Mass.) 21.1 5.5 6 The Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, 207,538 24.7 21.1 Oklahoma 7 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, 183,343 Wehco Media (Ark.) 22.1 DNR Arkansas 8 The Providence Journal, Rhode Island 167,609 Belo (Texas) 17.3 DNR Page 1 Rank Newspaper, State Weekday Ownership Circulation Staff non-white % circulation area non- for previous year white % (year-end 2002), if paper responded 9 Las Vegas Review-Journal, Nevada 160,391 Stephens Media Group 39.8 DNR (Donrey) (Nev.) 10 Daily Herald, Arlington Heights, 150,364 22.6 5.7 Illinois 11 The Washington Times, District of 102,255 64.3 DNR Columbia 12 The Post and Courier, Charleston, South 98,896 Evening Post Publishing 35.9 DNR Carolina (S.C.) 13 San Francisco Examiner, California 95,800 56.4 18.9 14 Mobile Register, Alabama 95,771 Advance (Newhouse) 33.0 8.6 (N.Y.) 15 The Advocate, -

Station Fire BAER Revisit – May 10-14, 2010

United States Department of Agriculture Station Fire Forest Service Pacific Southwest BAER Revisit Region September 2009 Angeles National Forest May 10-14, 2010 Big Tujunga Dam Overlook May 11, 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to express thanks to the following groups and individuals for their efforts for planning and holding the Revisit. Thanks to all the Resource Specialists who participated; Jody Noiron - Forest Supervisor; Angeles National Forest Leader- ship Team; Lisa Northrop - Forest Resource and Planning Officer; Marc Stamer - Station Fire Assessment Team Leader (San Bernardino NF); Kevin Cooper - Assistant Station Fire Assessment Team Leader (Los Padres NF); Todd Ellsworth - Revisit Facilitator (Inyo NF); Dr. Sue Cannon, US Geological Survey, Denver, CO; Jess Clark, Remote Sensing Application Center, Salt Lake City, UT; Pete Wohlgemuth, Pacific Southwest Research Station-Riverside, Penny Luehring, National BAER Coordinator, and Gary Chase (Shasta-Trinity NF) for final report formatting and editing. Brent Roath, R5, Regional Soil Scientist/BAER Coordinator June 14, 2010 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. -

Caldor Fire Incident Update

CALDOR FIRE z INCIDENT UPDATE Date: 9/9/2021 Time: 7:00 a.m. Information Line: (530) 303-2455 @CALFIREAEU @CALFIRE_AEU @EldoradoNF Media Line: (530) 806-3212 Incident Websites: www.fire.ca.gov/current_incidents @CALFIREAEU https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7801/ @EldoradoNF Email Updates (sign-up): https://tinyurl.com/CaldorEmailList El Dorado County Evacuation Map: https://tinyurl.com/EDSOEvacMap INCIDENT FACTS Incident Start Date: August 14, 2021 Incident Start Time: 6:54 P.M. Incident Type: Wildland Fire Cause: Under Investigation Incident Location: 2 miles east of Omo Ranch, 4 miles south of the community of Grizzly Flats CAL FIRE Unit: Amador – El Dorado AEU Unified Command Agencies: CAL FIRE AEU, USDA Forest Service – Eldorado National Forest Size: 217,946 Containment: 53% Expected Full Containment: September 27, 2021 First Responder Fatalities: 0 First Responder Injuries: 9 Civilian Fatalities: 0 Civilian Injuries: 2 Structures Threatened: 24,647 Structures Damaged: 80 Single Residences Commercial Properties Other Minor Structures 778 18 202 Destroyed: Destroyed: Destroyed: ASSIGNED RESOURCES Engines: 320 Water Tenders: 82 Helicopters: 43 Hand Crews: 59 Dozers: 52 Other: 34 Total Personnel: 4,532 Air Tankers: Numerous firefighting air tankers from throughout the state are flying fire suppression missions as conditions allow. CURRENT SITUATION WEST ZONE The fire continued to be active throughout the night. Minimal growth occurred in the Situation Summary: northeast and southern areas of the fire perimeter. Firefighters worked diligently last night picking up minor spot fires and mitigating threats to structures. Today crews will continue Incident Information: working along the southern edge to secure more control line and keep the fire north of Highway 88. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Risk Management Committee Safety Gram 2018

SAFETY GRAM 2018 Fatalities, Entrapments and Accident Summary for 2018 (http://www.nwcg.gov/committees/risk-management-committee/resources) The following data indicates the fatalities, entrapments, burnovers and fire shelter deployments during calendar year 2018. The information was collected by the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center and verified by the NWCG Risk Management Committee. Fatalities Incident Name Agency/Entity Number # Date Type of Jurisdiction Activity of Personnel of Shelters Fatalities Injuries/Treatment Accident Location Involved People Deployed 1/26 Puerto Rico Pack Test Work Capacity Test Local Government Medical 1 1 Cardiac Arrest Fatality Arduous San Juan Puerto Rico 2/28 Water Tender Accident Initial Attack Local Government Vehicle 3 1 2 injured, 1 fatality Fatality VFD New London TX 3/10 Grass Fire Fatality UNK Local Government UNK 1 1 Incident date: 3/10 Ellinger VFD (Suspected Medical) Deceased: 3/23 TX 3/12 Hazard Tree Mitigation Chainsaw Federal Medical 1 1 Fell unconscious, Fatality Operations USFS transported to Olympic NF hospital. Deceased WA 3/15 Grass Fire Fatality Initial Attack Local Government Medical 1 1 Fell ill and collapsed UNK Heart Attack on 3/16. OH Deceased: 3/16 1 Incident Name Agency/Entity Number # Date Type of Jurisdiction Activity of Personnel of Shelters Fatalities Injuries/Treatment Accident Location Involved People Deployed 4/12 Shaw Fire Initial Attack Local Government Entrapment 2 1 1 fatality; 1 FF with Cheyenne 2nd degree burns. OK 4/18 Rocky Mount Fatality Initial Attack Local Government Medical 1 1 Neck and back pain VA VFD on 4/18. Deceased: 4/19 4/21 Training Hike Fatality Fitness Training State Medical 1 1 Collapsed, treated on CA Dept. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

2012 Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers American Asian Indian American Black Hispanic Multi-racial Total American Asian The News-Times, El Dorado 0.0 0.0 11.8 0.0 0.0 11.8 Indian American Black Hispanic Multi-racial Total Times Record, Fort Smith 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.3 3.3 ALABAMA Harrison Daily Times 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Alexander City Outlook 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Daily World, Helena 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Andalusia Star-News 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Sentinel-Record, Hot Springs National Park 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The News-Courier, Athens 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Jonesboro Sun 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News 0.0 0.0 20.2 0.0 0.0 20.2 Banner-News, Magnolia 0.0 0.0 15.4 0.0 0.0 15.4 The Cullman Times 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Malvern Daily Record 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Decatur Daily 0.0 0.0 13.9 11.1 0.0 25.0 Paragould Daily Press 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Enterprise Ledger 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Pine Bluff Commercial 0.0 0.0 25.0 0.0 0.0 25.0 TimesDaily, Florence 0.0 0.0 4.8 0.0 0.0 4.8 The Daily Citizen, Searcy 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Fort Payne Times-Journal 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Stuttgart Daily Leader 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Valley Times-News, Lanett 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Evening Times, West Memphis 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Press-Register, Mobile 0.0 0.0 8.7 0.0 1.4 10.1 CALIFORNIA Montgomery Advertiser 0.0 0.0 17.5 0.0 0.0 17.5 The Bakersfield Californian 0.0 2.4 2.4 16.7 0.0 21.4 The Selma Times-Journal 0.0 0.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 Desert Dispatch, Barstow 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 -

Staff Summary for April 15-16, 2020

Item No. 30 STAFF SUMMARY FOR APRIL 15-16, 2020 30. SHASTA SNOW-WREATH CESA PETITION Today’s Item Information ☐ Action ☒ Consider and potentially act on the petition, DFW’s evaluation report, and comments received to determine whether listing Shasta snow-wreath (Neviusia cliftonii) as a threatened or endangered species under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) may be warranted. Summary of Previous/Future Actions • Received petition Sep 30, 2019 • FGC transmitted petition to DFW Oct 10, 2019 • Published notice of receipt of petition Nov 22, 2020 • Public receipt of petition Dec 11-12, 2019; Sacramento • Received DFW 90-day evaluation report Feb 21, 2020; Sacramento • Today, determine if petitioned action Apr 15-16, 2020; Teleconference may be warranted Background A petition to list Shasta snow-wreath as endangered under CESA was submitted by Kathleen Roche and the California Native Plant Society on Sep 30, 2019 (Exhibit 1). On Oct 10, 2019, FGC staff transmitted the petition to DFW for review. A notice of receipt of petition was published in the California Regulatory Notice Register on Nov 22, 2019. California Fish and Game Code Section 2073.5 requires that DFW evaluate the petition and submit to FGC a written evaluation with a recommendation, which was received at FGC’s Feb 21, 2020 meeting. The evaluation report (Exhibit 2) delineates each of the categories of information required for a petition, evaluates the sufficiency of the available scientific information for each of the required components, and incorporates additional relevant information that DFW possessed or received during the review period. Today’s agenda item follows the public release and review period of the evaluation report prior to FGC action, as required in Fish and Game Code Section 2074. -

2020 July August September Statewide Fires Situation

State Operations Center Situation Status Report 2020 July/August/September Statewide Fires September 20, 2020 – 1800 hours Report No. 33 Incident Summary The State Operations Center is activated to support and monitor ongoing wildfire activity occurring in multiple areas throughout the state. Confidentiality Notice This document is for the sole use of the intended recipient(s) and may contain confidential and privileged information. Any unauthorized review, use, disclosure, or distribution is prohibited without the express written consent of the Cal OES Executive Office. Situation Report 2020 July/August/September Statewide Fires Report Date: 9/20/2020 Report Time: 1800 Weather Summary – National Weather Service (NWS) Increasing southwest winds gusting up to 30 mph across the Southern California Mountains and much of the Sierra Range Monday through Wednesday. o Elevated to locally critical fire weather conditions are likely each day, especially across Southern California. A few showers could bring light rain to Del Norte and Humboldt Counties on Wednesday. Weather Watches and Warnings Northern California: o NSTR Southern California: o NSTR Northern California Valley Foothills/Mountains Temps: Lows: 55-65°F, Highs: 85-90ºF Temps: Lows 35-50°F, Highs: 65-75ºF Humidity: Night: 75-85%, Day: 20-30% Humidity: Night: 35-45%, Day: 15-25% Winds: Light and variable tonight, shifting south Winds: Terrain-driven 5-10 mph tonight, shifting to southeast 5-15 mph Monday. southwest 10-15 mph with gusts to 25 mph over the Sierra Monday. Winds along the coastal ranges mainly west to northwest 10-15 mph. Precipitation: Dry Precipitation: Dry Southern California Coast Inland Temps: Lows: 60-65°F, Highs: 75-85ºF Temps: Lows 65-75°F, Highs: 90-105ºF Humidity: Night: 90-100%, Day: 60-70% Mtns: Lows 50-60°F, Highs: 75-80ºF Winds: Light and variable tonight, becoming Humidity: Night: 20-40%, Day: 10-25% west to southwest 5-10 mph Monday. -

WUI Program...1

Page 1 Ferguson Fire - Brush Engine 1 Crew INSIDE THIS QUARTER: WUI Program................... 1 Calls & Response Stats.... 2 Mutual Aid Assignments. 2 This year’s WUI program was a success with a total clearance of 235 Prevention Unit Stats...... 3 acres. The crew performed fuels reduction around the residences, tribal buildings, and road system on the reservation. Defensible space Traffic Accidents.............. 4 was maintained up to 100 feet around the homes and tribal buildings. Fireline Medic.................. 4 The program runs each year from June through September with a Training & Testing........... 5 crew between 7 to 10 individuals, including a crew boss and assistant Misc.................................. 6 crew boss. The Bureau of Indian Affairs funded Email the Battalion Chief’s this year’s WUI program by way of [email protected] mkennedy@pechanga -nsn.gov grant at a total of $109,252.00. [email protected] Or Call Pechanga Fire Department at (951)770-6001 Page 2 Pechanga Fire Department Quarterly Report Pechanga Fire Department personnel actively participated in this year’s wildland fires, CALLS both operational and administratively. The following is a breakdown of fire personnel that participated in mutual aid assignments this quarter. EMS Calls 273 Fires 10 . FC Chris Burch: Dispatched to the Klamathon Fire in Siskiyou County on July 5th, and Public Assistance 2 the Carr Fire in Shasta County on July 25th as Planning Section Chief, working closely Good Intent 27 with the Incident Commander to plan and organize the tactics, strategy and False Alarms 3 resources needed to suppress the fire. Hazardous Condition 1 .