(Ratae Corieltauvorum) 210AD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Leicester Walking Trail

THE FRIENDS OF JEWRY WALL MUSEUM * ROMAN LEICESTER * WALKING TRAIL WELCOME TO ROMAN LEICESTER – RATAE CORIELTAVORUM Archaeologists suspect that a military garrison was established This walking tour takes you through modern Leicester at Leicester soon after the Roman conquest of Britain in AD 43, to the location of key Roman sites and buildings that have been probably on the site of an existing British settlement next to the lost and found (and sometimes lost again) - look out for the east bank of the River Soar. Heritage Panels as you go for more information about different periods in Leicester’s history. The walk will take you near many In Roman times Leicester was known as Ratae Corieltavorum. other sites of interest including the medieval suburb of Ratae comes from the Celtic word ‘ratas’, for the ramparts that The Newarke, Newarke Houses Museum, The Guildhall and we think protected the pre-Roman settlement. It was a capital Leicester Cathedral – final resting place of King Richard III. of the Corieltavi people who controlled the surrounding territory, and much of the East Midlands. The main part of the walking trail should take between an Ratae developed throughout the Roman occupation of Britain hour and 90 minutes to complete, at a moderate pace (stops 1-8). and by the late 3rd Century AD was a successful walled town It has as an extension of three additional sites (stops 9-11) and with trading links across the province and the Roman Empire - a another three a little further afield (stops A-C). We hope that the rectangular street grid featured important public buildings, exploring Leicester’s busy, multi-cultural streets gives you a ornate townhouses, shops, industrial sites and at least one temple. -

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

A Modern History of Britain's Roman Mosaic Pavements

Spectacle and Display: A Modern History of Britain’s Roman Mosaic Pavements Michael Dawson Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 79 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-831-2 ISBN 978-1-78969-832-9 (e-Pdf) © Michael Dawson and Archaeopress 2021 Front cover image: Mosaic art or craft? Reading Museum, wall hung mosaic floor from House 1, Insula XIV, Silchester, juxtaposed with pottery by the Aldermaston potter Alan Gaiger-Smith. Back cover image: Mosaic as spectacle. Verulamium Museum, 2007. The triclinium pavement, wall mounted and studio lit for effect, Insula II, Building 1 in Verulamium 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of figures.................................................................................................................................................iii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................v 1 Mosaics Make a Site ..................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................1 -

EXCAVATIONS at HIGH CROSS 1955 by ERNEST GREENFIELD and GRAHAM WEBSTER

EXCAVATIONS AT HIGH CROSS 1955 by ERNEST GREENFIELD and GRAHAM WEBSTER INTRODUCTION The excavations at High Cross were made necessary by the road widening and diversion scheme across this known Roman site. The work was organised as an emergency by the Ministry of Works (as it was then known), Inspec torate of Ancient Monuments. It was carried out in two stages, the first at Easter 1955, when arrangements were made at short notice under the impres sion that road works were imminent. The initial intention was to examine Area I, but on arrival at the site it was discovered that the landowner was still in possesion and unwilling to allow any work to take place. As the con tractor had already assembled his gang and equipment and it was believed that the road works were due to start within a matter of weeks, the director (Graham Webster) decided faute de mieux to attempt a running line of tren ches along the headland on the south side of the road with the hope at least of finding evidence of buildings and/or civil or military defences which could be developed at a later stage. The whole of the first stage of excavation was thus limited to a stretch of ground not more than ten to twelve feet wide, for which permission was obtained from a different owner. Conditions were not improved by wretched weather and at one stage the trenches were all filled with water to within six inches of ground level. There were no dis coveries of any real significance and the scatter of occupation with its scanty structural elements could not be fully interpreted in the method which it was necessary to adopt. -

8 Water and Decentring Urbanism in the Roman Period: Urban Materiality, Post-Humanism and Identity

Adam Rogers 8 Water and Decentring Urbanism in the Roman Period: Urban Materiality, Post-Humanism and Identity Abstract: In this chapter, the relationship between water and urbanism in the Roman period is examined by looking at the ways in which water formed part of the urban fabric and the implica- tions of this for understanding urban development, urban lives and identities, that decentres approaches to Roman urbanism. Water reminds us that the dualism of ‘natural’ and ‘human- made’ components of settlements and landscapes needs to be studied and brought together through meaningful frameworks of analysis. ‘Decentring’ urbanism draws on different perspec- tives of urbanism and allows us to move away from the top-down Romanocentric approach to urban studies and look for additional perspectives and experiences. The example of water al- lows us to explore urbanism by looking at landscape, religion and ritual, and identity and experience. The paper focuses on the towns of Britain in the Roman era, with case studies of Colchester (Camulodunum), St Albans (Verulamium), London (Londinium), Lincoln (Lindum) and Winchester (Venta Belgarum), and reflects on the way in which provinces across the Em- pire differed in the nature of urban development and urban experience. There was no one Roman world, but many different worlds in the Roman era where there were different identities and experiences. Introduction This paper examines water as a component of towns in the Roman period and how we can look at the implications of water forming part of the urban materiality. Water can be used to develop decentred perspectives on these settlements and the experiences of inhabitants. -

Verulamium, 1949*

We are grateful to St Albans Museums for their permission to re-publish the photographs of the Verulamium excavations. www.stalbanshistory.org May 2015 Verulamium, 1949* BY M. AYLWIN COTTON and R. E. M. WHEELER URING the past decade, field archaeology in Great Britain has been conditioned by certain D obvious factors. Most of it has been emergency work, the hasty salvage of bombed sites or of sites required urgently by the Armed Services, by factories, by housing schemes, or by related operations such as gravel-digging. Owing to the diversion of talent into fieldwork of another kind, and the temporary cessation of archaeological field-training, the demand for skilled supervisors has exceeded the available supply. More trained workers have been needed urgently. There have indeed been certain encouraging responses to this need. In the north, Professor I. A. Richmond and Mr. Eric Birley, have been conducting an annual school at Corbridge in connection with the University of Durham. The University of Nottingham Depart- ment of Adult Education has conducted summer training schools since 1949 under the directorship of Dr. Philip Corder and Mr. M. W. Barley, in which students have been trained on a Roman site of consider- able importance. In the south, the Institute of Archaeology of the University of London, for five weeks in the summer of 1949, organised a course of training by means of excavation, lectures and classes in survey- ing, draftsmanship and photography at Verulamium, where an excellent site-museum, then under the active curatorship of Mrs. Audrey Williams, fortified by a traditional local interest in such matters, provided special facilities within reach of London. -

Excavations at Fordcroft, Orpington

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society POVEREST ROAD •--- 48 ••••••.. \ 21 asp • 34 37 • (// 111 22 49: •, 14 53S 28. .27 • 18 •14a • 30 43 12 1 t 38 51to0 19 i,3-6\ 17'‘64 (35 > •16 cab • 15 42 47 31 d. ( .9 45 - 130 2 0 PH 50 29 *52 r — • 8 41 32 57 7 •••-•-• 40 c/4_•-•/.7.358 4 55 6 „ 2 • 1-- 0 PH 0 70 , --, .-- —. 1, a --""--; ,,.......--- .. - - - - , 60 -- 63 - --. .-- •--- iI % It t.........0 PH I r--- 1 I 64 '` \ 1 '162 „ ROMAN69'9PIT ) BELLEF1ELD ROAD 10 20 FIG. 1. Plan of the Anglo-Saxon. Cemetery at Orpington. [face p. 89 EXCAVATIONS AT FORDCROFT, ORPINGTON CONCLUDING REPORT By P. J. TESTER, F.S.A. THn first part of this report continues the description of the Anglo- Saxon cemetery at Orpington published in the last volume of Arch. Cant., lxxxiii (1968), 125-50, and deals particularly with the discoveries made in the two seasons 1967-68. In Part II the Romano-British features occurring on the same site as the Anglo-Saxon burials are described, and details of the pottery, coins and other finds of Roman age are provided in appendices. At present no further opportunities for excavation are available as digging has been extended as far as the roads forming the north and south limits of the site, and also to the houses on the east and west. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following have given sustained help with the digging during 1967-68: Mesdames M. -

Chickens in the Archaeological Material Culture of Roman Britain, France, and Belgium

Chickens in the Archaeological Material Culture of Roman Britain, France, and Belgium Michael Peter Feider A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bournemouth University April 2017 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 2 Abstract Chickens first arrived in northwest Europe in the Iron Age, but it was during the Roman period that they became a prominent part of life. Previous research on the domestication and spread of chickens has focused on the birds themselves, with little discussion of their impact on the beliefs and symbolism of the affected cultures. However, an animal that people interact with so regularly influences more than simply their diet, and begins to creep into their cultural lexicon. What did chickens mean to the people of Roman Britain, France, and Belgium? The physical remains of these birds are the clearest sign that people were keeping them, and fragments of eggshell suggest they were being used for their secondary products as well as for their meat. By expanding zooarchaeological research beyond the physical remains to encompass the material culture these people left behind, it is possible to explore answers to this question of the social and cultural roles of chickens and their meaning and importance to people in the Roman world. Other species, most notably horses, have received some attention in this area, but little has been done with chickens. -

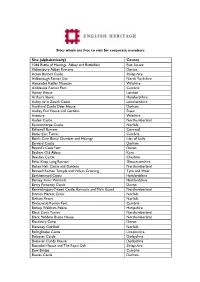

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are FREE TO VISIT for Corporate Members Opening times vary, pre-booking may be required, please check English Heritage website for details. Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Appuldurcombe House Isle of Wight Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham d's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blackfriars, Gloucester Gloucestershire Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire 1 Boscobel House and The -

Lucerna 36, July 2008

Newsletter 36, July 2008 lucerna 36 1 lucerna 36 l u c e r n a Subscriptions 2007/8 Roman Finds Group Thank you to everyone who has paid the Newsletter 36 subscription promptly this year and to those who have paid their outstanding debts. We still have a number of subscriptions outstanding for Contents the current year, so if you are one of the culprits, please send me your cheque, made out Small Finds in the Bigger Picture..............3 to the Roman Finds Group. We do not want to A valedictory forbidding mourning ……10 lose anyone, but postal prices are increasing and A little poser from Einfield …………….11 if subscriptions remain unpaid, members will be Study Day Review ……………………..13 removed from the mailing list. Obituary for John Dore ………………...16 RFG Committee ………………………..17 The subscription remains at £8 for an individual Books …………………………………..18 and £11 for two people at the same address. If News, conferences, study days ………...22 payment by standing order would be more convenient, I can send the form, which can also Notes for contributors be downloaded from the RFG web site. Contributions are always welcome – particularly on Angela Wardle new finds –so please send them to us, and share RFG Treasurer them with the rest of the Roman Finds Group! 1 Stebbing Farm, Fishers Green Stevenage, Herts. SG1 2JB E-mailed text should be sent as either a .doc, .txt or .rtf file. Please use sufficient formatting to make We hope you enjoy this newsletter and please don't the hierarchy of any headings clear, and do not forget to get in touch with any interesting articles or embed illustrations of graphs in the text but send information you'd like to share with other members. -

Volume Two Appendix 1: Catalogue of Known, Suspected and Possible Villa Sites in Britain 4Ppendix 1 Introduction to the Catalogue of Known, Suspected and Possible

Volume Two Appendix 1: Catalogue of Known, Suspected and Possible Villa Sites in Britain 4ppendix 1_ Introduction to the Catalogue of Known, Suspected and Possible Roman Villas in Britain The existence of some villas can be held to be self-evident: they have been at least partially excavated and shown to be rectilinear masonry buildings, perhaps with baths, mosaics arid hypocausts. However, before a site is actually excavated - or given a thorough geophysical or successful aerial survey - it is difficult to discern its exact nature. Any surface scatter of Roman artefacts, particularly building debris, may indicate the presence of a villa. This presents the thorniest of problems to the compiler of a catalogue of possible villa sites, for a field scatter of Roman material may also represent the site of a temple, a mansio, a small town, a 'native settlement' or even a heavily manured field. Yet field scatters must be taken into account, because they may prove to be villas. They are certainly likely to prove to be a settlement of some sort. Even a light field scatter belies a much greater amount of material beneath the surface. Ebcperiments by Ainmerman (1985) and Parker- Pearson (pers. comm.) on the relationship of surface to sub-surface artefact densities have demonstrated that a relatively small amount of material - as little as 2% of the total - is present on the surface at any one time. These results have been confirmed with Roman material in Britain by Gaffney and Tingle (1985) at Maddle Farm (BK27) and by Hayfield at 1harram (NK37)(pers. Comm.).