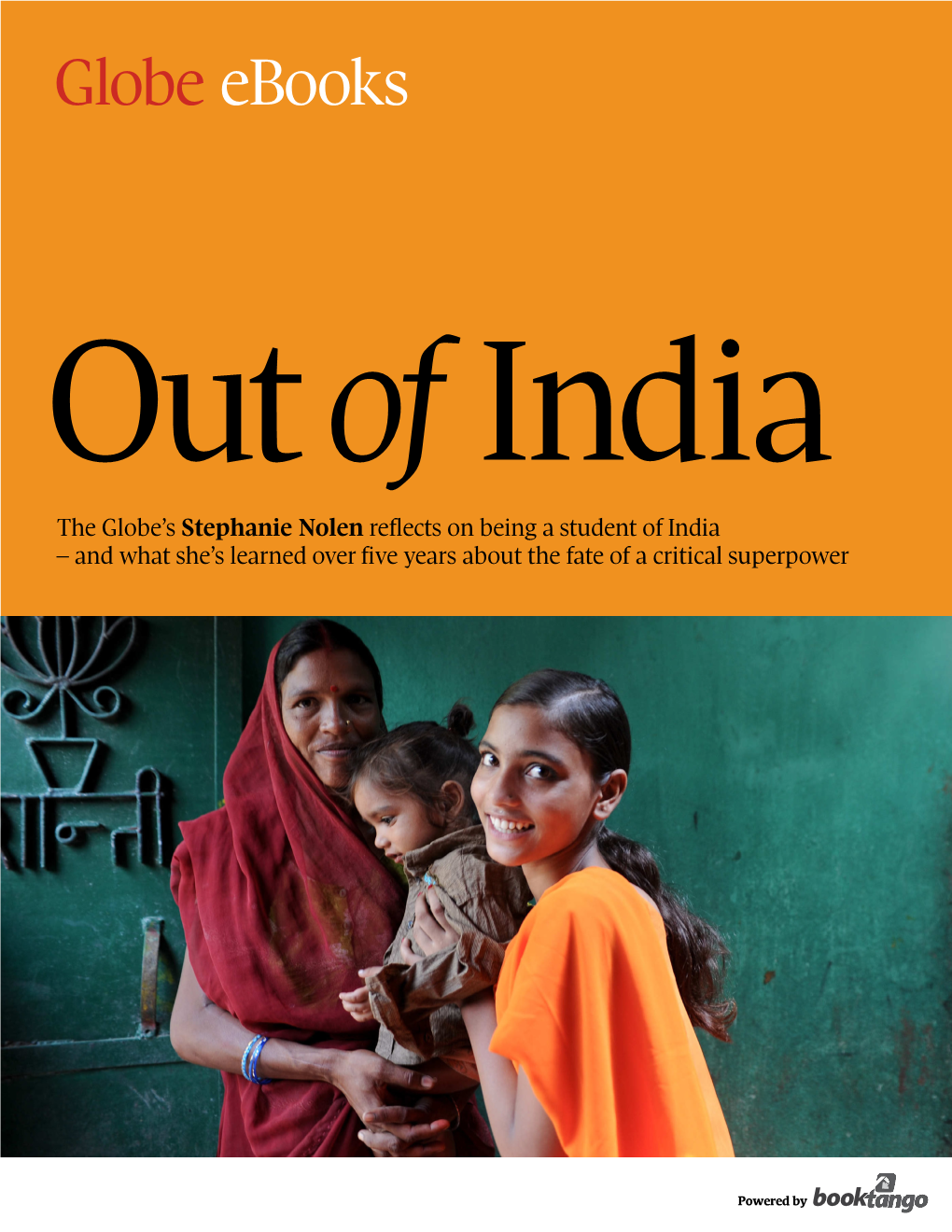

The Globe's Stephanie Nolen Reflects on Being a Student of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PATNA Annual Report 2019-2020 CONTENTS 2 | P a g e Annual Report 2019-2020 DIRECTOR’S ADDRESS Annual reports of an institute depict the stages of progress the institute has made over the years- step by step. These are valuable documents recording the history of an institute. IIT Patna- a member of the group of 2G IITs- was set up in 2008. Institutes of higher learning have intellectual, social, cultural, economic and moral responsibilities. Through academics and extra-curricular activities such institutes do man making and contribute to the wealth of the nation. IIT Patna too has been shouldering and will continue to shoulder the responsibility of nation-building. The highlight of 2019-20 has been the momentum with which infrastructure creation and expansion has been continuing. There is continuous progress with recruitment, R & D funding and construction- new hostels, new workshops, new academic buildings etc.. IIT Patna has always been responsive to and responsible for local needs. The interaction with the state continues to be mutually fulfilling. Many new academic programs have been approved in the senate and the Board including MBA with AI specialization, B.Tech in Engineering Physics, BS in Economics, B.Tech in Mathematics and Computing, B.Tech in AI and Data Sciences and so on. Our aim is to reach the figures of 3000 students, 300 faculty members and 330 staff members in 2 years time. Our parent ministry's- MHRD's- continued support in this growth and expansion endeavour is gratefully acknowledged. As we end the period Apr 19- Mar 20, we face a situation hitherto unseen. -

Unpaid Dividend-17-18-I3 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 696104.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 54.00 23-May-2025 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 23-May-2025 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE ROOM NO 6 G 15 M L CAMP 12044700-01567454- Amount for unclaimed and A ARUNCHETTIYAR AKCHETTIYAR INDIA Maharashtra 400019 10.00 23-May-2025 MATUNGA MUMBAI MI00 unpaid -

November 2020 Jivan | November 2020 in This Issue

JIVAN | NOVEMBER 2020 JIVAN | NOVEMBER 2020 IN THIS ISSUE PUBLISHER & PRINTER November 2020 Antony Pitchai Vedamuthu, SJ EDITOR Vinayak Jadav, SJ COPY EDITOR Mark Barco, SJ EDITORIAL ADMINISTRATOR Dharmesh Barot DESIGNER Vinod Kuriakose EDITORIAL BOARD Astrid Lobo Gajiwala Evelyn Monteiro, SCC Myron Pereira, SJ Job Kozhamthadam, SJ C. Joe Arun, SJ CORRESPONDENTS John Rose, SJ (West Zone) Victor Edwin, SJ (North Zone) A. Irudayaraj, SJ (South Zone) Patrick Pradhan, SJ (North Eastern Zone) Rolphy Pinto, SJ (Overseas) PUBLISHED AT Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, P.B. No. 70, Martyrdom and Jesuits of South Asia 04 St. Xavier’s Road, Anand-388001, Gujarat. Let us together make a diff erence 07 PRINTED AT Anand Press, Gamdi, Anand-388001, Gujarat. Contemplation in Political Action 10 CONTACT FOR PUBLICATION The Editor, JIVAN, St. Xavier’s College Campus Ahmedabad-380009 Blessed Emilio Moscoso, SJ: First Martyr of Ecuador 13 Cell : +91 97234 49213, Ph. : 079 2960 2033. E-mail : [email protected] JRS-South Asia: 40 years of Accompaniment 14 Website: www.jivanmagazine.com CONTACT FOR SUBSCRIPTION & A.T. Thomas: Liberator of the Oppressed and Exploited 18 CIRCULATION The Publisher, Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, P.B. No. 70, Anand-388001, Gujarat. Cell : +91 94084 20847, Thomas Gafney: A Prophet against Corruption and Drugs 20 Ph. : 02692 240161, E-mail : [email protected] Mathew Mannaparambil: A Voice against Dishonesty and Disloyalty 22 SUBSCRIPTION RATES OF JIVAN (Visit jivanmagazine.com for online subscription) James Kottayil: Emancipator from Moneylenders and Bonded-Labour 24 Jesuits: `1000 / yearly Non-Jesuits: Herman Rasschaert: Peacemaker among Religious Communities 26 `750 / yearly Foreign: US $25 (Or `1500) The Heaven I Imagine 27 / yearly Online Edition: `700 / yearly BON APPETIT 28 NEWS 29 GSP AC details A/C Name: GUJARAT SAHITYA PRAKASH SOCIETY IN MEMORIAM 31 CRUCIAL CONVERSATIONS 32 Bank Name: ICICI Bank Address: Flavours, Nr Bhaikaka November is the month of feasts of the Departed. -

Annual Report 2.Indd 1 9/23/2013 6:41:54 PM

Annual Report 2.indd 1 9/23/2013 6:41:54 PM Our Vision NEG-FIRE is a development support organisation that aims to transform lives of marginalised children through appropriate education and by strategic and dynamic partnership with local NGOs and community groups. We see every Dalit, Tribal, girl child and those belonging to vulnerable minority groups, learning to be confident young individuals, enabling them to relate to the world around them and providing the springboard to embark on higher academic or vocational; education in order to build an egalitarian society. Our Mission We enable partners to promote quality education for marginalised children resulting in social transformation in India while upholding the values of transparency, accountability, pluralism, equity, justice, peace and respect for all. 2 Annual Report 2.indd 2 9/23/2013 6:42:01 PM CONTENTS From the Chairperson 4 From the Executive Director 5 Partnership Promotion 7 Research and Documentation 19 Early Childhood Care and Development 25 Programme Monitoring and Evaluation 45 Trainings and Workshops 53 List of Board Members 2012-13 60 Financial Report 61 3 Annual Report 2.indd 3 9/23/2013 6:42:01 PM From the Chairperson It is my pleasure to present to the members of the General Body of NEG and the readers at large -the annual report of NEG-FIRE for the year 2012-13. As we witness the death of 22 children in the public school as a result of poisonous food served in the mid-day meal in Bihar on one hand and the young children hurling stones at the forces on the streets of Kashmir on the other hand, we feel very challenged and cannot escape the guilt of increasingly becoming irrelevant in the field of education. -

Solidarity Statement Against Police Brutality at Jamia Millia Islamia University and Aligarh Muslim University

Solidarity Statement Against Police Brutality at Jamia Millia Islamia University and Aligarh Muslim University We, the undersigned, condemn in the strongest possible terms the police brutality in Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi, and the ongoing illegal siege and curfew imposed on Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. On 15th December 2019 Delhi police in riot-gear illegally entered the Jamia Millia campus and attacked students who are peacefully protesting the Citizenship Amendment Act. The Act bars Muslims from India’s neighboring countries from the acquisition of Indian citizenship. It contravenes the right to equality and secular citizenship enshrined in the Indian constitution. On the 15th at JMIU, police fired tear gas shells, entered hostels and attacked students studying in the library and praying in the mosque. Over 200 students have been severely injured, many who are in critical condition. Because of the blanket curfew and internet blockage imposed at AMU, we fear a similar situation of violence is unfolding, without any recourse to the press or public. The peaceful demonstration and gathering of citizens does not constitute criminal conduct. The police action in the Jamia Millia Islamia and AMU campuses is blatantly illegal under the constitution of India. We stand in unconditional solidarity with the students, faculty and staff of Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University, and express our horror at this violent police and state action. With them, we affirm the right of citizens to peaceful protest and the autonomy of the university as a non-militarized space for freedom of thought and expression. The brutalization of students and the attack on universities is against the fundamental norms of a democratic society. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

Indian Feminist Theology and Women's Concerns Reviews, Resources and Remembrance

Indian Feminist Theology and Women's Concerns Reviews, Resources and Remembrance Pearl Drego Streevani Streevani Pune, 2013 2013 Indian Feminist Theology and Women's Concerns Reviews, Resources and Remembrance © Streevani and the author Published by: Streevani 1 & 2, Lotus Building, Neco Gardens, Viman Nagar, Pune 411 014. email: [email protected] Printed at: Repro Prints, Alok Nagari Building, Shop No. 2 & 3, Kasba Peth, Pune. Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... 5 Forward ............................................................................. 7 Part I 1. Indian Feminist Theology and Women's Concerns Reviews, Resources and Remembrance : Introduction...... 9 2. From survival needs to campaigns .................................... 13 3. Background trends worldwide .......................................... 15 4. Other Feminist Voices ....................................................... 21 5. Other International Locations ........................................... 24 6. Experience - Theory - Action ............................................ 26 7. Indian Women in Previous Decades .................................. 27 8. A Pioneer Publication ....................................................... 30 9. Women in India ................................................................. 30 Part II 10. Women in the Church......................................................... 34 11. Women in the 1970s .......................................................... 41 12. The 1984 Historic -

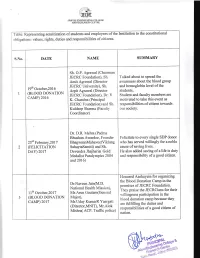

3Trtftl Ii I:: I

a . -j:.ri , . ',,3trtftl ii I:: i JAI PL:l? IiNailII gltl:\- (: tl0 L Ll:G l: ..tl{11 I{LSi:^ft{l fl CIiI-f Iltl Table: Representing sensitization of students and employees of the Institution to the constitutional cbiigations: values, dghts, duties and responsibilities of citizens. S.\o. DATE NAME SUMMARY Sh. O.P. Agrawal (Chairman JECRC Foundation), Sh. Talked about to spread the Amit Agraw'al (Director awareness about the blood group JECRC University), Sh. and hemoglobin level of the i9tr october,2016 Arpit Agrawal (Director students, 1 (BLOOD DONATION JECRC Foundation). Dt. V. Student and faculty members are CAMP) 2016 K. Chandna (Principal motivated to take this event as JECRC Foundation) and Sh. responsibilities of citizen towards Kuldeep Sharma (Facultl' our society. Coordinator) Dr. D.R. Mehta (Padma Bhushan Awardee, For"rnder Felicitate to every single SDP donor 23'd February,2017 B hagwaanMahave erVi kl ang who has served willingly for a noble 2 (FELICITATION SahaytaSamiti) and Sh. cause of saving lives. DAY) 20i7 Devendra Jhajharia( Gold He also added saving of a life is duty Medalist Paralympics 2004 and responsibility of a good citizeru and2016) Honured Aashayein for organizing the Blood Donation Camp in the Dr.Naveen Jain(M.D. premises of JECRC Foundation. National Health Mission), They praise the JECRCians for their Gautam(General 11th October,2Oll Mr.Arun the a uillingness parlicipation in J (BLOOD DONATION Major), blood donation camp because they CAMP) 2017 Mr.Uday KumarR Yaargati are fulfilling the duties and (Director,MNIT), Mr.Alok responsibilities of a good citizen of Mishra( ACP, Traffic police) nation. -

Report of Working Group on National Rural Livelihoods Mission (Nrlm)

REPORT OF WORKING GROUP ON NATIONAL RURAL LIVELIHOODS MISSION (NRLM) September 2011 PLANNING COMMISSION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Contents Acknowledgments 3 Preface 4 Chapter 1: Introduction 6 Chapter 2: Review of NRLM Framework for Implementation 13 Chapter 3: Review of MKSP Guidelines 54 Chapter 4: Framework for working with CSOs in NRLM 57 Chapter 5: Summary of the Recommendations 65 Annexure 1: Members of Working Group 78 Annexure 2: Summary of Regional Consultations 79 Acknowledgements The Working Group on National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) of the Planning Commission would like to thank Dr. Mihir Shah, Member of Planning Commission, for constituting the Working Group with a clear mandate to review NRLM and MKSP and make recommendations for the 12th Plan. We are thankful to the Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, for extending all the necessary support and cooperation for the NRLM Working Group in conducting the regional consultations and e-discussions to enrich the report of the Working Group. We would like to particularly thank Mr. BK Sinha and Mr. T Vijay Kumar for their encouragement, participation and support. The NRLM mission document and framework for implementation were developed through a participatory process engaging diverse stakeholders in the sector. For the Working Group, it has been a real challenge to make useful recommendations on NRLM as NRLM is in the inception phase. The contributions made by the participants of the five regional consultations, those that participated in the UNDP Solution Exchange discussions and also in the roundtables that UNDP and the Working Group jointly organized were of high quality and substantial enabling the Working Group to come up with this report. -

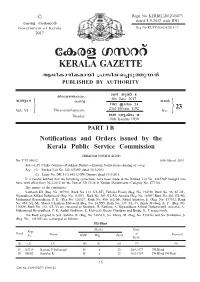

Part 1St B Set 1

© Regn. No. KERBIL/2012/45073 tIcf k¿°m¿ dated 5-9-2012 with RNI Government of Kerala Reg. No. KL/TV(N)/634/2015-17 2017 tIcf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[nImcnIambn {]kn≤s∏SpØp∂Xv PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Xncph\¥]pcw, 2017 Pq¨ 6 hmeyw 6 sNmΔ 6th June 2017 \º¿ 1192 CShw 23 } 23rd Idavam 1192 } 23 Vol. VI Thiruvananthapuram, No. 1939 tPyjvTw 16 Tuesday 16th Jyaishta 1939 PART I B Notifications and Orders issued by the Kerala Public Service Commission ERRATUM NOTIFICATION No. P VI 590/12. 30th March 2015. Sub.—L.D. Clerk—Various—Palakkad District—Erratum Notification—Issuing of —reg. Reg.—(1) Ranked List No. 142/12/DOP dated 30-3-2012. (2) Letter No. DR. I (1) 845/12/GW Dummy dated 19-3-2015. It is hereby notified that the following corrections have been made in the Ranked List No. 142/DOP brought into force with effect from 30-3-2012 for the Post of LD Clerk in Various Departments (Category No. 477/10). The names of the candidates: Santhosh KR (Reg. No. 197991, Rank No. 113, S/L-ST), Fathima Emam (Reg. No. 194728, Rank No. 96, S/L-M), Niyasudheen Alikkal Puthanveetil (Reg. No. 131537, Rank No. 389, S/L-M), Aneesha (Reg. No. 163097 Rank No. 402, S/L-M), Muhmmed Riyasudheen, P. K. (Reg No. 126627, Rank No. 450, S/L-M), Abdul Shukoor, E. (Reg. No. 197302, Rank No. 484, S/L-M), Sheeja Chandran Melveetil (Reg. No. 182995, Rank No. 137, S/L-V), Bindu Pradeep, K. P. -

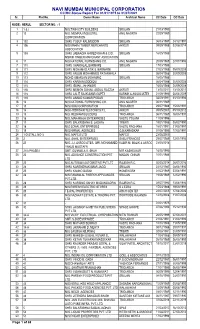

Ccocstatus Nodewise.Rpt

NAVI MUMBAI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION CC/OC Status Report For 01/01/1975 to 31/07/2021 Sr. Plot No. Owner Name Architect Name CC Date OC Date NODE : NERUL SECTOR NO. : 1 1 1 & 3 M/S.TWIN CITY BUILDERS SRUJAN 21/03/1990 2 10 M/S. MEMRAJ INDUSTRIL ANIL NAGRTH 22/09/1989 CORPORATION 3 102 SHRI. YUSUF KALIMUDDIN SRUJAN 06/03/1987 24/12/1991 4 106 M/S MAHIM TIMBER MERCHANTS AKRUTI 09/09/1988 02/06/2014 ASSOCIATION 5 109 SHRI. JABAAGIR AHMED KHAN & C/O. SRUJAN 16/05/1988 MSHIM TIMBER MARCHANT ASOCIATION 6 11 M/S NATIONAL FURNISHING CO., ANIL NAGRTH 20/09/1989 27/07/1993 7 110 SHRI. SHAIKHLAL BARMARE SRUJAN 17/03/1988 8 111 SHRI. MOHAMAD ATIK S. BARMARE 21/03/1988 05/09/2009 9 112 SHRI. ANJUM MOHAMMED PATANWALA 08/04/1988 20/09/2008 10 113 MOHD UMARJAN MOHAMAD SRUJAN 16/05/1988 11 114 SHRI. KARIM M SIDDIQUI 06/04/1988 20/09/2008 12 115 SHRI. ISMAIL JAHANGIR 16/05/1988 20/09/2008 13 116 SHRI. MEMON SUHAIL ABDUL RAZZAK AKRUTI 13/10/2011 13/10/2011 14 118 SHRI. LALIT RAJKUMAR GUPTA KARNIK & ASSOCIATES 21/09/1990 08/04/2009 15 119 SHRI. ANAND KUMAR PODAR TRIO ARCH 02/09/1991 31/10/1994 16 12 M/S NATIONAL FURNISHING CO., ANIL NAGRTH 06/11/1989 17 13 M/S NIKKI GORPORATION TRIO ARCH 29/07/1988 15/03/1991 18 14 M/S.HYDROAIR TECTONICS P.L. AKRUTI 05/05/2007 05/10/2012 19 15 M/S.