Chapter 8 the Working Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bottesford Parish Walks (PDF, 1

(Unfortunately, dogs are prohibited from this grassy l2 Continue right through the tunnel of trees and then area. Follow the road around to meet point B). take the track on your left. l3 Cross the stream and continue to follow the track Bottesford l Aiming for the far left hand corner of the green, leave B around to the left, now with the hedge on your left. In This leaflet is one of a series produced to promote by the gate just behind the trees, and turn right up about 200 metres leave the track and turn right onto circular walking throughout the county. You can obtain Easthorpe Road. Bottesford a path with the field edge on your right. Follow this others in the series by visiting your local library, Just past the estate cottages follow the enclosed path hedge to the corner of the field and pass through a Tourist Information Centre or download them from circular indicated to the right. The path comes out at the small gate. www.leics.gov.uk/paths. walks playing fields with an opportunity to have a swing! 2 l4 Turn left and after 50 metres, turn right across the field Bottesford 1 2.7kms/1.7 miles The present village hall was built in 2003 on the site of to another gate in the hedge opposite. Cross three Muston 2 7.4kms/4.6 miles the original Victory Commemoration Hall, a former army fields towards Normanton village. Before the path takes Redmile building. A time capsule has been placed in the fabric you into Normanton, look out for a stile on your left, in of the new hall to preserve the village memories, past the left-hand corner of the field. -

NCA 48: Trent & Belvoir Vales Key Facts & Data

NCA 48: Trent & Belvoir Vales Key Facts & Data T his document provides a correspond to national data. If summary of environmental data you have any questions about collected for the NCA. It is the Key Facts and Data, please intended to help guide anyone contact: making decisions that may [email protected] affect the local environment. .uk. Your feedback will help The information contained here shape the content of the full is collated from the best NCA profiles, which will be available national datasets. It is published from September recognised local information 2012 onwards. may provide additional detail and that this will not always www.naturalengland.org.uk Map of Trent & Belvoir Vales Total Area: 177,604 ha The above map is provided from the Countryside Character Area description pending completion of NCA maps. It is recognised that the content of this map may now be out of date in some cases and is included for general reference only. New maps will include updated content and be provided within the full NCA profiles, due to be completed by 2013. 1. Landscape and Nature Conservation Designations There are no national landscape designations within this NCA. Source: Natural England (2011) 1.1 Designated nature conservation sites The NCA includes the following statutory nature conservation designations: Tier Designation Designated Area in Proportion Site(s) NCA of NCA International n/a n/a 0 ha 0% European Special n/a 0 ha 0% Protection Area (SPA) Special Area of n/a 0 ha 0% Conservation (SAC) National National Nature Muston 20 ha <1% Reserve (NNR) Meadows NNR National Site of Special A total of 33 685 ha <1% Scientific sites wholly or Interest (SSSI) partly within the NCA Source: Natural England (2011) Please Note: (i) Designated areas may overlap (ii) all figures are cut to Mean High Water Line, designations that span coastal areas/views below this line will not be included. -

The Old Windmill 20 the Green, Barkestone Le Vale Leicestershire Ng13 0Hh £250000

11 Market Place Bingham Nottingham NG13 8AR Tel: (01949) 87 86 85 [email protected] THE OLD WINDMILL 20 THE GREEN, BARKESTONE LE VALE LEICESTERSHIRE NG13 0HH £250,000 THE OLD WINDMILL, 20 THE GREEN, BARKESTONE LE VALE, LEICESTERSHIRE NG13 0HH A substantial detached & characterful home 1345 sq ft of deceptively large accommodation Three / four bedrooms Delightful secluded & private garden to the rear Large double driveway A truly fascinating individual detached character property which offers a wealth of accommodation and features, situated at the heart of this pretty Vale of Belvoir village. As the name suggests, The Old Windmill is one of the original Windmills positioned within the Vale of Belvoir. Having fallen out of use at the beginning of the 20th Century, works began in the early 1980s to bring the Old Windmill back to its former glory with a complete overhaul when it was turned over to residential accommodation, with a wonderful homely atmosphere and likely to appeal to a wide audience. The property occupies a delightful plot with two main garden areas, the first to the rear is a sunny and private Courtyard (a perfect place to enjoy a glass of merlot or a G & T), with an archway leading into the second and more established garden area with mature trees and shrubs. This southerly facing Views across the rear garden towards Belvoir Caslte on the distance garden is perfect for those looking for a private and secure area away from the hustle and bustle of City life! HOW TO FIND THE OLD WINDMILL From the 'top room' there are views across the Vale of Belvoir towards Belvoir Castle up on the hill. -

GLEBE FARM BARN WALTHAM LANE EATON MELTON MOWBRAY ! Please Refer to 'Designer Risk Assessment' for Further Information Regarding Mitigation of Hazards

Notes: Copyright retained in accordance with the copyright design and patents act 1988. Dimensions must not be scaled from this drawing. The contractor is to check and verify all building and site dimensions before work is commenced. The Contractor is to check and verify with all Statutory Authories and Employer the local and condition of any underground or overhead services or confirm that none exist A stunning new barn conversion project in a wonderful Vale of Belvoir setting with breathtaking views… prior to work commencing on site. CDM Regulations 2015: Denotes a significant hazard or difficult to manage procedure. GLEBE FARM BARN WALTHAM LANE EATON MELTON MOWBRAY ! Please refer to 'Designer Risk Assessment' for further information regarding mitigation of hazards. LEICESTERSHIRE NG32 1SH CDM Regulations, require all projects to: - Have workers with the correct skills, knowledge, training and experience. - Contractors providing appropriate supervision, instruction and information. - A written Construction Phase Plan. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Swain Architecture are appointed as 'Designer' only, unless appointed by the client in writing to Anticipated completion with NHBC Structural Warranty – late Spring 2021 confirm Swain Architecture's role as 'Principal Designer'. A unique opportunity to acquire a mellow stone and brick period barn conversion in a breathtaking setting on high ground above the highly regarded village of Eaton, in the heart of the Vale of Belvoir, by respected developer Willett Homes. Land & Estate Agents The Country Property Specialists Property Consultants www.smithandpartners.co.uk Visualisation 1 not to scale Client: Mr & Mrs L.Willett Project: Glebe Farm, Walham Lane, Eaton Drawing: Proposed Visualisation 1 revA Number: S03.20.204.08 W: www.swainarchitecture.com Date: March 2020 E: [email protected] T: 0115 972 7685 Paper Size: A3 Scale: N/A Mohan Business Centre, Tamworth Road, Long Eaton, Nottingham, Drawn By: HH Checked By: Rev Description Date NG10 1BE. -

Melton and Rushcliffe Landscape Sensitivity Study 17 August 2014

MBC and RBC Ashfield Landscape Sensitivity and District Capacity Study Gedling District Newark and Amber Valley (B) Sherwood District (B) Broxtowe District District (B) Figure 3.4: Mill Farm Landscapes and Views of windmill Borough-wide Importance 23 Melton and Rushcliffe Borough Councils City of Nottingham Surrounding authorities (B) 25 28 Primary landmark Erewash 28 Secondary landmark District (B) 24 28 Secondary landmark (Church spires & towers) 22 Belvoir South Approximate angle of view 19 Castle Kesteven 20 7 from notable viewpoints 26 District Landscape Character Assessment Unit South Derbyshire 21 1 : Vale of Belvoir District 1 4 2 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Belvoir Scarp 3 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Dalby to Belvoir Wolds 4 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Knipton Bowl 7 16 18 5 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Ragdale to Saltby Wolds Mill Farm 6 2 windmill 3 6 : Kesteven Uplands: Saltby and Sproxton Limestone Edge 17 7 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Belvoir, Stapleford and North West 5 Croxton Parkland Leicestershire 27 8 : High Leicestershire Hills: Great Dalby and Gaddesby District Pastoral Farmland 9 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Wreake Valley 10 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Eye Valley 11 : High Leicestershire Hills: Gaddesby Valley 14 13 5 15 Wymondham 12 : High Leicestershire Hills: Burrough Hills windmill 13 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Freeby, Buckminster and 10 Wymondham Farmland 7 9 10 14 : The Leicestershire Wolds: Asfordby Quarry 15 -

The Haven, 29 Main Street, Muston, Leicestershire Ng13 0Fb

11 Market Place Bingham Nottinghamshire NG13 8AR 01949 87 86 85 [email protected] THE HAVEN, 29 MAIN STREET, MUSTON, LEICESTERSHIRE NG13 0FB £325,000 THE HAVEN, 29 MAIN STREET, MUSTON, LEICESTERSHIRE NG13 0FB A 2 or 3 bedroomed detached BUNGALOW on a substantial plot with a southerly facing and very sunny private rear garden - a rural and picturesque setting, as its name suggests - with professionally landscaped gardens to both front and rear - and with views of Belvoir Castle on the horizon! Set within the colourful gardens are a vegetable patch, a wildlife sanctuary and a 'natural' pond as well as numerous plantings which ensure a colourful view throughout the year. The recent upgrades that have been carried out by the current owners include the brand new kitchen which was fitted in 2020 and the substantial GARDEN ROOM that overlooks the glorious gardens. To the front is an ornate and well planned garden which ensures a rolling pattern of colour throughout the months with neat pathways of lawn separating the plantings. The gardens are completed by a much larger than average GARAGE and a separate GLASS HOUSE which enjoys plenty of sunshine for those green- fingered amongst us. The feeling throughout the bungalow is one of charm and character of a bygone age and yet with the benefits of a new kitchen and bathroom... the perfect combination. The tranquil, unspoilt village of Muston is situated just off the A52 affording excellent road links to Nottingham, Leicester, Grantham and the A1. The high speed rail link from Grantham to London Kings Cross takes just over an hour. -

MELTON • Melton Mowbray Heritage Trail • Aspects of Melton Mowbray MELTON • Gourmet Taste of Leicestershire • What’S on in Melton Mowbray, Events Calendar

. p e t s r o o d s t i n o s e i r e t a e e n i f e h t f o e n o ! o w t . n o i t i t e p m o c . t c e r i d r e g a n a M e r t n e C n i g n i n e v e e h t f f o h s i n i f d n a e s u o h - e r u t c i p . r e f f o o t s a h n o t l e M s e c n e i r e p x e . s y a w e l d i r b f o s e l i m g n o l a k c a b e s r o h r o f 9 0 1 £ t s u j r o f k a e r b t r o h s e r i h s r e t s e c i e L g n i k a b s d n a l d i M t s a E e h t r e t n e d n a r i a F n w o T n o t l e M e h t t c a t n o c e s a e l p , s e c n e i r e p x E a m e n i C l a g e R d e h s i b r u f e r e u q i n u e h t t a 0 1 t a e r g e h t f o e m o s e r o l p x e u o y p l e h l l i w e d i u g n o e d i s y r t n u o c e r i h s r e t s e c i e L e h t e r o l p x E 5 0 1 f o e t s a T t e m r u o G e u l a v t a e r g e h t e c n e i r e p x E y r t n u o C n o t l e M t a d a e r b l a e r e k a b d n a e t s a T e t s a T l a c o l k o o b r o e c i v r e s t e e r g d n a t e e m n o t l e M 5 e c n e i r e p x e c i t a m e n i c l u f r e d n o w a n i t h g i l e D s i h T . -

I .. Eicestersiiire

88 BILTON. I.. EICESTERSIIIRE. [KI!:LLY'S BELTON. Farmer Herbert & Robert, blacksmiths Sutton Joseph. farmer Blakeney Rev. William Newcome B A Field John Michael, George P.R Toone Eliza Jane (Miss), beer retailer (vicar), Vicarage . '/Gibson Elizabeth (Mrs.), shopkeeper, & Upton Thomas, wheelwright llentley Charles, Forest View villa post office Wilson J oseph, beer retailer Gilbert James, baker lit shopkeeper Woulidge Benjamin, farmer, Manor farm COMMERCIAL. Gough Edward, butcher Barker Henry, farmer Husbands ·Wm. frmr. Low. Merrill grnge Barnett Thomas, frmr. Top Merrill grnge Husbands William, jun. farmer GRACE DIEU. Botham Edwin, farmer, Middle Merrill Hyde .John, Queen's Head P.R Booth Rt. Hon. Charles' P.C., F.R.S. grange IKnight Eobert, farmer Grace Dieu Manor house; & 24 Brooks James & Joseph, farmers Parker Joseph, grazier Great Cumberland place, London w Burton Frederick, farmer Room Godfrey, grocer Green Joseph (Mrs.) & Son, farmers Chester George, corn miller (water) Room William, shoe maker Hoult John, farmer, Warren farm Cuffin Jolm, grocer, draper, rate col- Rose John, farmer Pares WiIliam & Herbert, farmers 'lector & assistant overseer ,Shaw Samuel, shoe maker Vesty Richard Handley, farmer BEL VOIR (formerly an extra-parochial liberty) is now Petty Sessions are held at the Peacock hotel, every alter- a parish, and head of an Out-Relief Union, 2 miles south nate monday, at 12 noon. The places in the petty ses- from Redmile station on the Great Northern and London sional division are :-Belvoir, Barkstone, . Bottesford, and North Western joint railways, 7 west-south-west from Branston, Croxton-Kerrial, Eastwell, Eaton, Harby, Grantham, 12 north-east from Melton Mowbray, 125 from Harston, Knipton, Muston, Plungar, Redmile, Saltby & London via MeltQn and 116 via Grantllam, and is the head Stathern. -

Bot129 090 Vv90 2017(4)

Village Voice Issue No. 90 July/August 2ot7 The newsletter of Bottesford, Easthorpe, Muston & Normanton Village Voice photo-competition winners On Sunday 4 June, the Village Voice arranged for a prize-giving ceremony at Bottesford Community Library. The event was hosted by award winning photographer and cinematographer I\4ark Plrgh of IvlP Pledia. lYark opened the ceremony by welcoming the winners, and explaining how high the standard was this year. "This is the 4th year we have run the competition, and each year the quality and creativity of the entries gets better." The winners were Ashley Waterfall, Geoff Foster and Katy Francis. The under 18 category was won by Ben Payne. I4ark presented a plaque to the winners and a certificate to the runners !p. It was good to see family members accompanying our winners. Katy's two boys, .lake and Luke, were very wel behaved and enjoyed the chocolate biscuits. Ben's mum and dad also came a ong to see him receive his prize. Ash ey unfortunately could not make the event as he comrnitted to photographing lhe Bel/es of Belvoir Cyclinq event, but the three remainjng contestants enjoyed a good chat with Mark about all things photographic and are looking forward to next year's competition. Full details will be announced later this year, Winners Ben, Geoff and Katy (recelvlng thetr ceitficates lelt) and Ashley (above). Late news - Village Voice Facebook page has 500 followers A very big thank you to everyone who follows us and contribLrtes to our Facebook page. We now have 501 foilowersl The idea for the page came from one of our previous editors Dilys Shepherd s daughter, Kate. -

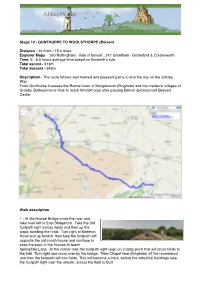

Stage 12. GUNTHORPE to WOOLSTHORPE

Stage 12 - GUNTHORPE TO WOOLSTHORPE (Belvoir) Distance - 24.9 km / 15.4 miles Explorer Maps - 260 Nottingham - Vale of Belvoir , 247 Grantham - Bottesford & Colsterworth Time: 6 - 6.5 hours average time based on Naismith’s rule Total ascent - 313m Total descent - 343m Description - The route follows well marked and pleasant paths to end the day on the Jubilee Way. From Gunthorpe it passes the Roman town of Margidunum (Bingham) and the medieval villages of Granby, Barkestone-le-Vale to reach Woolsthorpe after passing Belvoir (pronounced Beever) Castle Walk description 1 - At Gunthorpe Bridge cross the river and take road left to East Bridgeford. Take the 3rd footpath right across fields and then up the steps avoiding the road. Turn right at Kneeton Road and up Kirkhill, then take the footpath left opposite the old coach house and continue to pass the back of the houses to reach Springdale Lane. At the corner take the footpath right (sign on a lamp post) that will cross fields to the A46. Turn right and cross over by the bridge. Take Chapel lane (Bingham) off the roundabout and then the footpath left into fields. This will become a track, before the industrial buildings take the footpath right over the stream, across the field to Butt Playing Field. Cross the railway line and into the market square. 2 - Turn left in the square, towards the church and right along Cherry Street and across the road to the Byway. Turn right and left public footpath passing to the left of the leisure centre and right round the building to walk past flood-light pitches on the left and the athletics track. -

MEDICINE, POISON and WITCHCRAFT in the VALE of BELVOIR in the SEVENTEENTH CENTURY Ruth Crook

MEDICINE, POISON AND WITCHCRAFT IN THE VALE OF BELVOIR IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY Ruth Crook In seventeenth-century Leicestershire, six women were accused of witchcraft. Their alleged victims were the two sons of the Earl of Rutland. There is a possibility that the children both had symptoms of lead toxicity and porphyria. Henry, Prince of Wales, after staying at their home, also became ill and died. It is possible that he also may have been suffering from lead toxicity and porphyria. Belvoir Castle has overlooked the Vale of Belvoir, and parts of the counties of Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, for over 900 years, dominating an area in which most of the villages belonged to the estate of the lords who lived there. Four hundred years ago it was a place of tragedy, when the Earl of Rutland suffered the loss of two sons, events which eventually had dire consequences for another local family as well as his own. These events are well known, but it has never been suggested before that there may be a link between them and the death of Henry, Prince of Wales, in the weeks following a visit to Belvoir. Seventeenth-century people looked upon illness differently from how we do today. Generally, no-one knew what made them ill and often explained it as a result of the wrath of God, or the work of devils. If someone became ill, usually the women in the household would attempt to treat them with herbs and tinctures. For the literate, books such as Gervase Markham’s Countrey Contentments or the English Huswife, published in 1623, could be referred to. -

B E L V O I R C a S T L

BELVOIR CASTLE; With the SUCCESSION and INTERMARRIAGES of the FAMILY since the Conquest* * THE castle of BELLEVOIRE standith yn the utter Eagle in the county of Lincoln ; and Granby anl part that way of Leircesterfhir', on the very knape of Sutton, in the county of Nottingham. The duke has a highe hille, stepe up eche way, partely by nature, also in this neighbourhood the patronage of almost: partely by working of mennes handes, as it may as many churches, and a landed property of more evidently be perceyvid V Carhden describes it as in than 2o,oco/. a year. Lincolnshire; where he fays, " In the West part of This castle has been called by the different names Kelteven, on the edge of this county and Leicester- of Belvar, Beauvoir 6, Behidere % Bever, Bellovero, shire, stands Belvoir castle, so called (whatever was Belloviso, he.; and the etymology is easy, for few its antfent name) from the fine prospect on a steep places have so extensive a command of the country7* hill, which seems the work of arti."—" It stands up- It is situated upon the confines of Lincolnshire, at the on the top of a very lofty hill, containing from the termination of a, branch of the Leicestershire wolds^ foot to the top about 200 steps 5 yielding every way extending into the Vale of Belvoir to the North; a most delicious and pleasing prospect, being accounted and not only takes iti the Vale, but reaches over a one of the best prospects in the land : 1 have often rich and amazingly extensive country; which, front viewed this castle from the place where I dwell at Falde the elevation of the castle, appears in the several 8 near Tutbury, in the county of Stafford, with the help Views a dead flat .