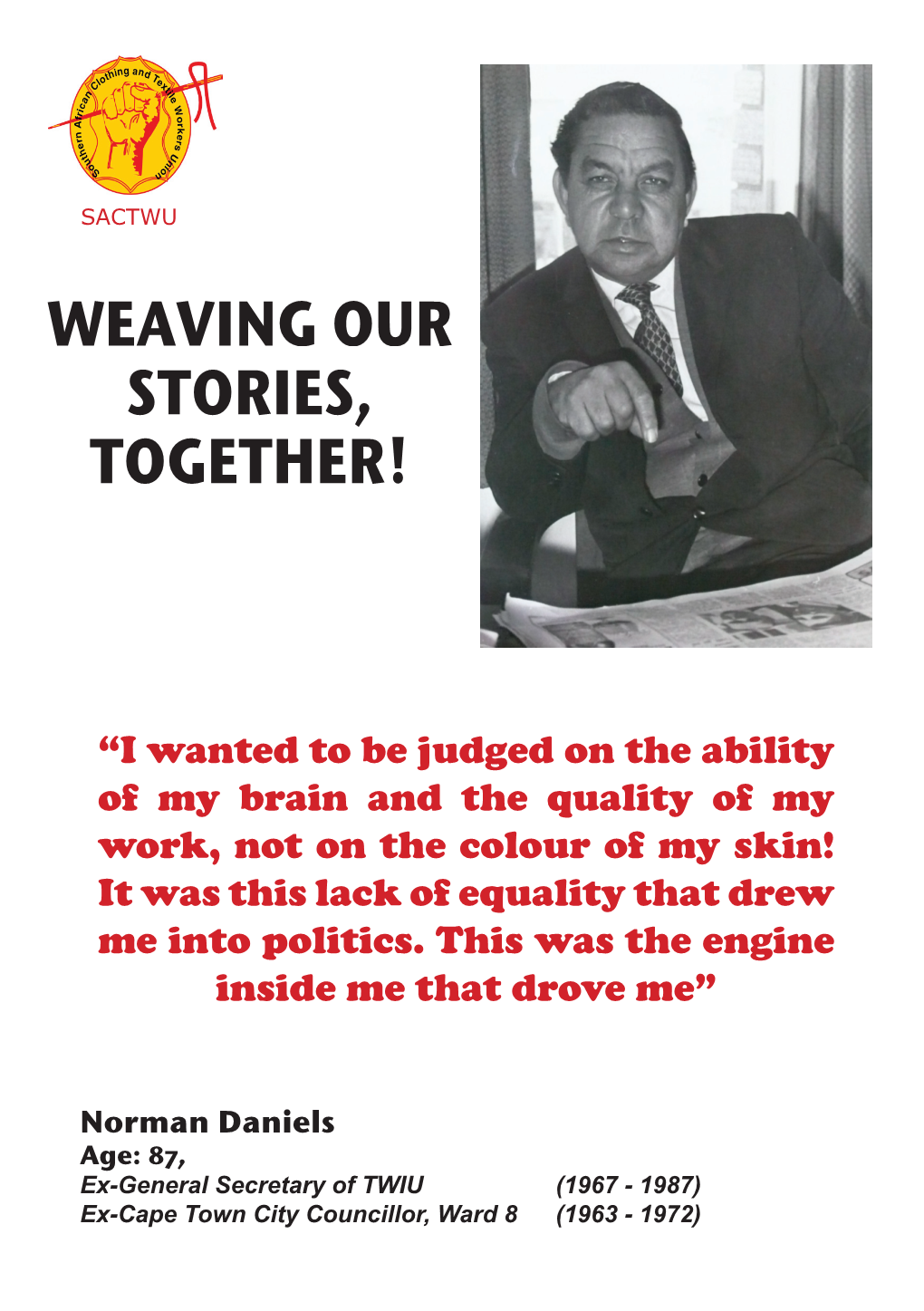

Mr Daniels.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasons Greetings '

Seasons’ Greetings Festive Message 2014 Dear Colleagues and Friends Life goes by so very fast, colleagues, and taking the On behalf of CPS, I would like to wish all of you time to reflect, even once a year, slows things down. that have the privilege of having a break over the We zoom past so many seconds, minutes, hours, with Christmas season a peaceful and joyful time relieved the frantic way we live that it’s important we take at of your rushed life and busy schedules. It was again least time to stop, take stock, and acknowledge our a year that was full of opportunities, which has just place in time before diving back into the frenzy of flown past. We need to sit down and reflect on work our daily lives! 2014 has gone, like the ones before it of the past year. … in a flash! The profession has had some challeng- I sincerely hope that you all have met the goals set es as it will always have and the secret is to look at it out for this year and will be prosperous in 2015 and from the perspective of opportunities and chances be able to utilise all the opportunities coming your that await us! way. Christmas is a very precious time to spend and Many things are thrown our way in this game of enjoy with family and friends. I trust that the mes- life. How you deal with them shows your true char- sage and joy of Christmas will have a special mean- acter. -

The Sanders Story a Family Saga

1 The Sanders Story A Family Saga Researched, compiled and transcribed by Derrick Lewis 2 “The path to strength and prosperity, to success in the future, lies in understanding the past. Know your origins, study the achievements of the generations before you and you will benefit from the wisdom of your ancestors” - The Old Testament 3 Preface I was born in Cape Town, South Africa in 1943, one hundred and one years after the birth of my maternal Great Grandfather, Wulf Sanders. My father, Isidore Lewis was fatally struck down by a massive coronary three years after my birth. Due to difficult financial circumstances at the time, my Mother decided to move in with her parents, Isidore and Bella Israelsohn who lived in the Southern Cape town of George. This is where I grew up, in my Grandparents home, at 72 York Street, George. The story that have compiled is a direct result of the many conversations I had with my Grandmother and listening to her many stories and anecdotes. I felt that as our family story was fascinating, the family having lived on three continents before arriving here in South Africa, I would write down and attempt to record all this fascinating oral history. Later in my adult years I researched these anecdotal facts and discovered most of them to be true! What I have finally written is a record of the life and times of the Sanders family with the assistance and input of the many members of our extended family. Chapter One We were Courlanders! Our story begins in Courland, now known as the provinces of Kurzeme and Zemgale, of modern day Latvia. -

~Llllil'i'11 1916 M 1917

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. .1 ••• f' '" DECO 51911 dI- tional Council ACQUISJ"Y-J'~,l'! if ~_.!'~,~.. e .. ~t '" !NUAl REPORT ~ J1ill!IIII'llllrl ~11!lilllli ~llllil'I'11 1916 M 1917 -.....tiiL ~ __ ... • " i .. NICRO (Registered under the Welfare Organisations Act: No. W.O. 313) provides help and constructive service for prisoners, prisoners' families and ex-prisoners at the foliowinJJ centres: .. Branch Address Tel. Bloemfontein P.O. Box 351. Bloemfontein 7-6678 Cape Town P.O. Box 10034, Cape Town 47-4000 Durban 2nd Floor, Trident Building, 6-6501 58 Field Street, Durban East London P.O. Box 1752, East London 2-4123 Johannesburg P.O. Box 11410. Johannesburg 23-1971 Kimberley Red Cross House, Stockdale Street, 2-6392 Kimberley Pietermaritzb u rg 16 Otto Street, Pietermaritzbu rg 2-5913 • Port Elizabeth 2a Dawson Street. Port Elizabeth 41-1542 Pretoria P.O. Box 468. Pretoria 2-5331 Springs P.O. Box 395. Springs 56-8911 • This essential work is co-ordinated and promoted by the NICRO NATIONAL COUNCIL , Benzal House, 3 Barrack Street, l' P.O. Box 10005, CALEDON SQUARE, " 7905 CAPE TOWN. Branch Reports are available on request 2 NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR CRIME PREVENTION AND REHABILITATION OF OFFENDERS Patron-in-Chief THE STATE PRESIDENT Patron THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE President THE HON. MR. JUSTICE P. J. WESSELS National Chairman , THE HON. MR. JUSTICE M. E. KUMLEBEN J Members of National Council The Hon. Mr. Justice G. Friedman Deputy Chairman Cape Town The Hon. Mr. Justice M. T. -

An Investigation Into Some Aspects of the Location of Clothing Retailers in Metropolitan Cape Town

MR IN LIBRARY C01 1006 9421 II I I I ...... •... AN INVESTIGATION INTO SOME ASPECTS OF THE LOCATION OF CLOTHING RETAILERS IN METROPOLITAN CAPE TOWN. Town Cape A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements -' for the degree of Master of Urban and ofRegional Planning. DAVID DEWAR B.A. (HONS) (CAPE TOWN) University OCTOBER, 1969. The -' .-.- ·---=-,~ _,..,·_ : ... ,.:,_ ;;c-,.-.c~·=::.c_.,:___ , _ _,_,_":::,-c,. -· ...., ·: ---c;~""-'' '-'.-,:· ,;·_::,..: ::_·o-,-"".."":-.:'7<:.:' :,;7'" • .·:.-"-:t' . ·-·;:;.-;.--:+ ...... !-.~:;'::: ~:-:•. -_.'.;\:."::.~-,~- ·- --;.· __ '::~ The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only.Cape of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University The ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i This writer is indebted to the following : Mr. K.S.O. Beaven, for invaluable help in the form of criticism, suggestions and computer programming. i:'· Mr. z.s. Gurzinski for many hours of stimulating discussion. Miss. Gillian Calderwood who gave up many hours of her time to write a computer ·programme for sequential analysis. Mr. Neil Dewar and Miss. M. Merkel who unselfishly offered and gave help in the fields of mapping and field work. Mrs. Hazel Goddard, the typist. To all these, sincere and grateful thanks are tendered. 1 ' .J '· ' .. ,I C 0 N T E N T S CHAPTER PAGE ACKNOWLEDGE~~NTS i LIST OF PLATES ii TABLES AND GRAPHS iii ONE INTRODUCTION 1 TWO THE PATTERN OF CLorHING RETAILERS IN METROPOLITJUi CAPE TOWN 4 ·-· TIIREE--:.~~--- -MICRO.:.ANAL'!s-rs-- OF -THE LOCATION- PATTERN --- IT - -- --- FOUR A STUDY OF SEQUENCES 33 FIVE THE INDIVIDUAL STORE 41 SIX A NEW APPROACH TO THE PROBLEM OF RETAIL LOCATION 54 \ ··-· -- ·- f REFERENCES. -

Capital Expenditure Project Listing

CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROJECT LISTING 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2016 NEDBANK GROUP ECONOMIC UNIT 07 February 2017 NOTES: Definition: The schedule is a listing of capital projects announced in the Republic of South Africa. It includes: Only projects valued at R20 million or more. Projects of an expansionary nature, i.e. capex which allows for an increase in the level of output, rather than pure replacement investment which involves the replacement of worn-out or outdated capital goods necessary for the continued operation and the maintenance of current output levels. The exceptions are: investment in equipment or machinery which reduces the harmful effects of pollution, and technological upgrading of equipment and machinery. Projects funded by both the private and public sectors. Projects reflecting direct foreign involvement. The listing is compiled on a sectoral basis, conforming to the Standard Industrial Classification. Limitations: Any analysis of the data needs to take account of the limitations outlined below: The schedule highlights significant areas of investment expenditure and not the absolute total value of all capital investment undertaken in the country. It serves as a rough guide to the general direction in which investment is moving and as an indication of the level of confidence in the economy. The full extent of replacement capital expenditure is not captured as mainly expansionary capital expenditure are published and recorded. In certain sectors a reliable indication of investment activity is not possible as typical investments are not large enough to be included in the schedule, even though the total capital expenditure in the sector may be substantial. -

The Transformation of the Sacks Futeran Buildings Into the Homecoming Centre of the District Six Museum

From family business to public museum: The transformation of the Sacks Futeran buildings into the Homecoming Centre of the District Six Museum. Hayley Elizabeth Hayes-Roberts 3079780 A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree M.A. in History (with specialisation in Museum and Heritage Studies) University of the Western Cape. Supervisor: Professor Ciraj Rassool Declaration I, Hayley E. Hayes-Roberts, hereby declare that this thesis ‘From family business to public museum: The transformation of Sacks Futeran buildings into the Homecoming Centre of the District Six Museum’ is my own work and that it has not been submitted elsewhere in any form or part, and that I have followed all ethical guidelines and academic principles as expressed by the University of the Western Cape and the District Six Museum. __________________________________________________ Hayley Hayes-Roberts, 23rd November 2012, Cape Town i Acknowledgements With heartfelt thanks to the staff of the District Six Museum: Tina Smith, Chrischené Julius Mandy Sanger, Bonita Bennett, Nicky Ewers, Estelle Fester, Margaux Bergman, Thulani Nxumalo, Dean Jates, Noor Ebrahim, Joe Schaffers, Linda Fortune, ex-residents and many others for your guidance, support, encouragement and friendship. Your work ethic and passion are a source of inspiration to me. I met and engaged with many individuals during my research that informed my thinking and to each and everyone who participated, listened, and provided guidance, I give my appreciative thanks. Mike Scurr, Rennie Scurr Adendorff Architects, Owen Futeran, Adrienne Folb, The Kaplan Centre, University of Cape Town, Melanie Geuftyn and Laddie Mackeshnie, Special Collections South African National Library, Cape Town and Jocelyn Poswell, Jacob Gitlin Library were most helpful and accommodating in my requests for material, interviews and information. -

Fish Hoek Looking Back

FISH HOEK LOOKING BACK by Joy Cobern Printed & Published by Fish Hoek Printing & Publishing cc P.O. Box 22165 Fish Hoek 7975 First Published 2003 1 PREFACE This book is not meant to be a full history of Fish Hoek but is intended for those living here or visiting who wish to know more about the area. I hope you enjoy it and end up knowing a little more about Fish Hoek. There are many people who have helped me and I would particularly like to thank Joe and Simone Frylinck, who really thought I could do it, Ethel may Gillard, for sharing her vast store of local information and fascinating reminiscences, Michael Walker and Clive Wakeford for encouragement and advice. To anyone else who thinks that they ought to be on that list, thank you too! 2 INDEX 1. Peers Cave……………………………………………………… 6 2. The First Explorations of the Fish Hoek Valley………………. 11 3. The Fish Hoek Farm……………………………………………15 4. The Early Days of the Village………………………………….. 23 5. Water and Electricity………………………………………….... 28 6. The Railway Comes to Fish Hoek……………………………... 33 7. Vischoek, Vishoek or Fish Hoek?................................................ 39 8. Beach Development…………………………………………….. 41 9. Beach Controversies……………………………………………. 48 10 Fish Hoek Main Road…………………………………………. 54 11. Early Businesses………………………………………………. 64 12. Local Government…………………………………………….. 70 13. The War Years…………………………………………………. 77 14. The Steps and Lanes…………………………………………... 81 15. Our Local Newspapers………………………………………... 85 16. The Battle of the Bottles………………………………………. 89 3 Fish Hoek 1922 Fish Hoek 1933 Fish Hoek 1947 4 1. Peers Cave Although the first plots in Fish Hoek were only sold in 1918 there have been people in the Fish Hoek Valley for many thousands of years, but it was only in the 1920's that the early history of the valley was uncovered. -

Chapter 13: Codes of Good Practice

Chapter 13 Codes of good practice There are codes of good practice dealing with picketing, sexual harassment, dismissals for operational requirements, and HIV/aids. 89 KNOW YOUR LRA Previously a code of good practice issued under the LRA could only be taken into account when interpreting or applying that Act. Now codes of good practice may be taken into account in interpreting or applying any employment law including: l the Occupational Health and Safety Act, 1993; l the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act, 1993; l the Labour Relations Act, 1995; l the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, 1997; l the Employment Equity Act, 1998; l the Skills Development Act, 1998; l the Unemployment Insurance Act, 2001. NEDLAC has published four codes of good practice. These are on: l picketing; l the handling of sexual harassment cases; l dismissals based on operational requirements; and l key aspects of HIV/aids and employment. Code of Good Practice on Picketing The Code of Good Practice on picketing provides practical guidance on picketing in support of a protected strike or in opposition to a lock-out. (See chapter 7 for more detail on the code.) 90 Codes of good practice Code of Good Practice on the handling of sexual harassment cases Sexual harassment is unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature and may include: l physical conduct; l unwelcome innuendoes; l sexual advances; l unwelcome gestures and indecent exposures; and l quid pro quo treatment (where an employer or supervisor attempts to influence the process of employment or promotion or training or discipline etc in exchange for sexual favours). -

1 September 2018 Dear Residents Spring Equinox in the Southern

September 2018 Dear Residents Spring Equinox in the Southern Hemisphere crept up on us in the wee hours of Sunday 23 September. Though most of us prefer to mark spring on 1 September, nature cares little about our rigid determinations! Spring lifts the spirits and brings wonderful messages of hope and renewal; how famous now are the flowers covering hills and valleys along the West Coast and Namaqualand and the whales arriving in our waters to calve! Media reports have reflected record whale sightings at De Hoop Nature Reserve along the Southern Cape coast. These included an albino calf. Albino calf, photographed by marine conservation photographer Jean Tresfon. Marine conservation photographer Jean Tresfon and whale scientist Chris Wilkinson’s aerial whale survey between Skipskop Point and Lekkerwater at De Hoop showed 1 116 whales, or 558 cow and calf pairs. They duo reports that Koppie Alleen along that coastline is now considered the most important southern right whale nursery along the South African coastline. 1 Colleague Els Vermeulen, who heads the Whale Unit, reported 1 347 southern right whales between Hawson and Witsands in August, a figure thought to be three times the number spotted there in 2017. In an era of shrinking biodiversity, this is good news indeed! A burst of spring colour on The Terrace, the clivia in full bloom. At The St James a fresh, new spring look graces the reception and buffet areas of Gentrys dining room, where the carpets have been replaced by beautiful, non-slip tiles, in keeping with and continuing the welcoming ambience of our entrance hall. -

Ugly Duckling Bmw’S 2000C Odd Ball Developed Into the Jaw-Dropping Cs

LAND ROVER JAGUAR SIMOLA HILLCLIMB DKW MUNGA R47.00 incl VAT • August/September 2014 UGLY DUCKLING BMW’S 2000C ODD BALL DEVELOPED INTO THE JAW-DROPPING CS CHEVROLET APACHE YAMAHA RD350 Stock look, hot under the hood A fast appreciating 2-wheeler BRIAN FERREIRA | MILLE MIGLIA | AL GIBSON FOR BOOKINGS 0861 11 9000 proteahotels.com REV IT UP! TO BOOK THIS & MANY MORE GREAT MOTORING SPECIALS VISIT proteahotels.com DURBAN MOTOR SHOW DURBAN EXHIBITION CENTRE, 7TH-9TH OF NOVEMBER 2014 The Durban Motor Show is back for its 3rd instalment with exciting new features showcasing the best of what the motoring industry has to offer while providing the ultimate family day out. The show was founded in 1992 by the Veteran Car Club and the Durban Early Car Club, first held at Westridge Tennis Stadium but today its hosted by the Durban Exhibition Centre from the 7th-9th of November. What are you waiting for, book your stay now! Remember, if you book 30 days or more before arrival you save 20% on our best available rate. URBAN TRANQUILLITY SET IN THE HUB #COOL #COOLER #COOLEST #FROSTBITE. OF THE UMHLANGA RIDGE We just get consistently cooler each year. After taking the NEW TOWN CENTRE. crown for SA’s coolest hotel group in the Sunday Times Experience urban tranquillity at Protea Hotel Umhlanga Ridge, Generation Next Awards in 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2013, we’re opposite the Gateway Theatre of Shopping and a short drive pleased to have won once again. Now we just wear gloves. to uMhlanga Beachfront. Voted the coolest hotel in 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 & 2014. -

The Application of Multivariate Statistical Techniques in the Analysis of Stock Market Data

UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICAL STATISTICS ************************** THE APPLICATION OF MULTIVARIATE STATISTICAL TECHNIQUES IN THE ANALYSIS OF STOCK MARKET DATA BY J.F, AFFLECK-GRAVES *************************** University of Cape Town A thesis prepared under the supervision of Professor C.G. Troskie and Associate Professor A.H. Money in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematical Statistics *************************** Copyright by the University of Cape Town 1977 - - ., , , '1ef"'1 r'v"ln The Univer~ \ty 0t r.r , '~ ~ , r Vl'P ii a 11 A t1 the rig rt to ren C ~ ' ~ ty t ,~ c.Jt~Qr • or in part. Copyn., 1L • The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town TO RITA C O N T E N T S CHAPTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 1.1 2 THE SELECTION OF CONSTITUENTS FOR A STOCK MARKET INDEX 2.1 Introduction 2.1 2.2 Methods of Constructing Stock 2.2 Market Indices 2.3 Elementary Selection Methods 2.6 2.4 A Cluster Analysis Method for 2.22 Selecting Stock Market Index Constituents 2.5 Conclusions 2.34 3 AN EMPIRICAL COMPARISON OF THE PERFORM ANCE OF DIFFERENT STOCK MARKET INDICES 3.1 Introduction 3.1 3.2 Types of Stock Market Indices 3.2 3.3 The Data 3.5 3.4 Tests and Results 3.10 3.5 Conclusions 3. -

Apexhi Annual Report 2005

APEXHI ANNUAL REPORT 2005 ONE INVESTMENT • TWO OPPORTUNITIES Contents Nature of business 3 Our track record 4 Vision, mission and objectives 5 Year at a glance 7 Highlights 9 Directors review 10 Directorate and administration 33 Profile of directors 34 Corporate governance 35 Report of the independent auditors 39 Certificate by company secretary 39 Directors report and statement of responsibility 40 Financial statements Balance sheet 42 Income statement 43 Statement of changes in equity 44 Cash flow statement 45 Notes to the financial statements 46 Analysis of unit holders 60 Details of property portfolio 61 Unit holders diary 68 Notice of annual general meeting 69 Notice of debenture holders meeting (A and B debentures) 72 Proxy form (annual general meeting) to the members Perforated Proxy form (A and B debenture holders meeting) Perforated ONE INVESTMENT • TWO OPPORTUNITIES 1 Nature of business LISTED PROPERTY COMPANY ApexHi Properties Limited (ApexHi ) is a property loan stock ( PLS ) company, which listed on the JSE Limited ( JSE ) in the Real Estate sector on 5 March 2001. The company offers investors a high-yielding, professionally managed portfolio of commercial, retail and industrial properties and is currently the third largest listed South African property company on the JSE, with a market capitalisation in excess of R4,0-billion. INNOVATIVE UNIT STRUCTURE ApexHi is the first and only listed property company to offer a unique structure with separately listed A and B units, which provides two investment opportunities, within one property portfolio. The A units are entitled to receive the first 102 cents per unit, per annum, or 45% of the distributable income, whichever is greater.