La Tène Wagon Models: Where Did They Come from and Where Did They Go?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overland-Cart-Catalog.Pdf

OVERLANDCARTS.COM MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES 2020 CATALOG DUMP THE WHEELBARROW DRIVE AN OVERLAND MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES PH: 877-447-2648 | GRANITEIND.COM | ARCHBOLD, OH TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Need a reason to choose Overland? We’ll give you 10. 8 & 10 cu ft Wheelbarrows ........................ 4-5 10 cu ft Wheelbarrow with Platform .............6 1. Easy to operate – So easy to use, even a child can safely operate the cart. Plus it reduces back and muscle strain. Power Dump Wheelbarrows ........................7 4 Wheel Drive Wheelbarrows ................... 8-9 2. Made in the USA – Quality you can feel. Engineered, manufactured and assembled by Granite Industries in 9 cu ft Wagon ...............................................10 Archbold, OH. 9 cu ft Wagon with Power Dump ................11 3. All electric 24v power – Zero emissions, zero fumes, Residential Carts .................................... 12-13 environmentally friendly, and virtually no noise. Utility Wagon with Metal Hopper ...............14 4. Minimal Maintenance – No oil filters, air filters, or gas to add. Just remember to plug it in. Easy Wagons ...............................................15 5. Long Battery Life – Operate the cart 6-8 hours on a single Platform Cart ................................................16 charge. 3/4 cu yd Trash Cart .....................................17 6. Brute Strength – Load the cart with up to 750 pounds on a Trailer Dolly ..................................................17 level surface. Ride On -

Public Auction

PUBLIC AUCTION Mary Sellon Estate • Location & Auction Site: 9424 Leversee Road • Janesville, Iowa 50647 Sale on July 10th, 2021 • Starts at 9:00 AM Preview All Day on July 9th, 2021 or by appointment. SELLING WITH 2 AUCTION RINGS ALL DAY , SO BRING A FRIEND! LUNCH STAND ON GROUNDS! Mary was an avid collector and antique dealer her entire adult life. She always said she collected the There are collections of toys, banks, bookends, inkwells, doorstops, many items of furniture that were odd and unusual. We started with old horse equipment when nobody else wanted it and branched out used to display other items as well as actual old wood and glass display cases both large and small. into many other things, saddles, bits, spurs, stirrups, rosettes and just about anything that ever touched This will be one of the largest offerings of US Army horse equipment this year. Look the list over and a horse. Just about every collector of antiques will hopefully find something of interest at this sale. inspect the actual offering July 9th, and July 10th before the sale. Hope to see you there! SADDLES HORSE BITS STIRRUPS (S.P.) SPURS 1. U.S. Army Pack Saddle with both 39. Australian saddle 97. U.S. civil War- severe 117. US Calvary bits All Model 136. Professor Beery double 1 P.R. - Smaller iron 19th 1 P.R. - Side saddle S.P. 1 P.R. - Scott’s safety 1 P.R. - Unusual iron spurs 1 P.R. - Brass spurs canvas panniers good condition 40. U.S. 1904- Very good condition bit- No.3- No Lip Bar No 1909 - all stamped US size rein curb bit - iron century S.P. -

Austria As a 'Baroque Nation'. Institutional and Media Constructions

Austria as a ‘Baroque Nation’. Institutional and media constructions Andreas Nierhaus Paris, 1900 When Alfred Picard, General Commissioner of the World Exhibition in Paris 1900, declared that the national pavilions of the ‘Rue des Nations’ along the river Seine should be erected in each country’s ‘style notoire’, the idea of characterizing a ‘nation’ through the use of a specific historical architectural or artistic style had become a monumental global axiom. Italy was represented by a paraphrase of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice, Spain chose the look of the Renaissance Alcazar, the United States selected a triumphant beaux-arts architecture, Germany moved into a castle-like building – in the style of the "German Renaissance", of course – and the United Kingdom built a Tudor country house. However, there were considerable doubts about the seriousness and soundness of such a masquerade: ‘Anyone wanting to study national styles at the Quai d' Orsay would fail to come to any appreciable results – just as the archaeologist who wants to collect material for costume design in a mask wardrobe [would equally fail]. Apart from few exceptions, what we find is prettily arranged festive theatrical decoration (...).’1 Whereas the defenders of modernism must have regarded this juxtaposition of styles as symbolic of an eclecticism that had become almost meaningless, both the organizers and the general public seemed very comfortable with the resulting historical spectacle. It was no coincidence that the Austrian Pavilion was given the form of a Baroque castle. (Fig. 1) Its architect Ludwig Baumann assembled meaningful quotes from the buildings of Johann Bernhard and Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach, Lucas von Hildebrandt and Jean Nicolas Jadot in order to combine them into a new neo-Baroque whole. -

Chapter Rd Roadster Division Subchapter Rd-1 General Qualifications

CHAPTER RD ROADSTER DIVISION SUBCHAPTER RD-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS RD101 Eligibility RD102 Type and Conformation RD103 Soundness and Welfare RD104 Gait Requirements SUBCHAPTER RD-2 SHOWING PROCEDURES RD105 General RD106 Appointments Classes RD107 Appointments RD108 Division of Classes SUBCHAPTER RD-3 CLASS SPECIFICATIONS RD109 General RD110 Roadster Horse to Bike RD111 Pairs RD112 Roadster Horse Under Saddle RD113 Roadster Horse to Wagon RD114 Roadster Ponies © USEF 2021 RD - 1 CHAPTER RD ROADSTER DIVISION SUBCHAPTER RD-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS RD101 Eligibility 1. Roadster Horses: In order to compete all horses must be a Standardbred or Standardbred type. Roadster Ponies are not permitted to compete in Roadster Horse classes. a. All horses competing in Federation Licensed Competitions must be properly identified and must obtain a Roadster Horse Identification number from the American Road Horse and Pony Association (ARHPA). An ARHPA Roadster Horse ID number for each horse must be entered on all entry forms for licensed competitions. b. Only one unique ARHPA Roadster Horse ID Number will be issued per horse. This unique ID number must subsequently remain with the horse throughout its career. Anyone knowingly applying for a duplicate ID Number for an individual horse may be subject to disciplinary action. c. The Federation and/or ARHPA as applicable must be notified of any change of ownership and/or competition name of the horse. Owners are requested to notify the Federation and/or ARHPA as applicable of corrections to previously submitted information, e.g., names, addresses, breed registration, pedigree, or markings. d. The ARHPA Roadster Horse ID application is available from the ARHPA or the Federation office, or it can be downloaded from the ARHPA or Federation website or completed in the competition office. -

KNJIGA Zbornik 58.Indd

FUNERARY PRACTICES DURING THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHEAST EUROPE Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium of Funerary Archaeology in Čačak, Serbia 24th – 27th September 2015 Beograd - Čačak, 2016 University of Belgrade National musem Faculty of Philosophy Čačak International Union for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences (UISPP) – 30th Commission: Prehistoric and Protohistoric Mortuary Practices Association for Studies of Funerary Archaeology (ASFA) – Romania FUNERARY PRACTICES DURING THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHEAST EUROPE Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium of Funerary Archaeology in Čačak, Serbia, 24th – 27th September 2015 Edited by Valeriu Sîrbu, Miloš Jevtić, Katarina Dmitrović and Marija Ljuština Beograd - Čačak, 2016 CONTENT RASTKO VASIĆ, Biography · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 6 RASTKO VASIĆ, Bibliography · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 9 INTRODUCTION · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 23 MIROSLAV LAZIĆ Magura – la Nécropole de l’Âge du Bronze à Gamzigrad à l’Est de la Serbie · · 29 MARIJA LJUŠTINA, KATARINA DMITROVIĆ Between Everyday Life and Eternal Rest: Middle Bronze Age in Western Morava Basin, Central Serbia · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 43 ANTONIU TUDOR MARC Mortuary Practices in the Wietenberg Culture from Transylvania · · · · · 53 CRISTIAN SCHUSTER Burials/Necropoleis vs. Settlements in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages in Wallachia (Romania) · · · · · · · · · · · · · 75 MARIO GAVRANOVIĆ Ladies First? Frauenbestattungen der Späten Bronzezeit und Frühen -

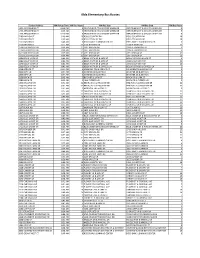

Elda Elementary Bus Routes

Elda Elementary Bus Routes Student Address AM Pickup Time AM Bus Route AM Bus Stop PM Bus Stop PM Bus Route 1399 ARROWHEAD CT 12:18 PM 6 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 1449 ARROWHEAD CT 8:45 AM 5 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 1449 ARROWHEAD CT 12:18 PM 6 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 2189 BANYON CT 8:40 AM 18 ROSS COUNTRY DAY ROSS COUNTRY DAY 18 2204 BANYON CT 8:40 AM 18 ROSS COUNTRY DAY ROSS COUNTRY DAY 18 2207 BANYON CT 8:48 AM 6 ROSS EARLY LEARNING CENTER ROSS EARLY LEARNING CENTER 6 2216 BANYON CT 8:11 AM 23 3738 HERMAN RD 3738 HERMAN RD 23 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 3 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 3 2251 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2397 BRENDA DR 21 2251 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2397 BRENDA DR 21 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 3 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 16 2270 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 2270 BELLA VISTA DR 16 2363 BELLA VISTA DR 8:43 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & CYPRESS LN BELLA VISTA DR & CYPRESS LN 3 2234 BERGER CT 12:13 PM 6 LEHMANN TRL & BERGER CT LEHMANN TRL & BERGER CT 5 2939 BETH LN 8:44 AM 6 JENNIFER DR & BETH LN JENNIFER DR & BETH LN 6 2939 BETH LN 8:44 AM 6 JENNIFER DR & BETH LN JENNIFER DR & BETH LN 6 2196 BIRCH DR 8:42 AM 3 BIRCH DR & LARK ST BIRCH DR & LARK ST 3 2283 BIRCH DR 8:43 AM 3 4016 CYPRESS LN BIRCH DR & CYPRESS -

History & STEM Fun with the Campbell County Rockpile Museum Wagons, Wagons, Wagons

History & STEM Fun with the Campbell County Rockpile Museum Wagons, Wagons, Wagons Covered wagons on Gillette Avenue - Campbell County Rockpile Museum Photo #2007.015.0036 To learn more about pioneer travels visit these links: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=4&v=GdbnriTpg_M&feature=emb_logo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fJFUYKIVKA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XmWtLrfR-Y Most wagons on the Oregon Trail were NOT Conestoga wagons. These were slow, heavy freight wagons. Most Oregon Trail pioneers used ordinary farm wagons fitted with canvas covers. The expansion of the railroad into the American West in the mid to late 1800s led to the end of travel across the nation in wagons. Are a Prairie Schooner and a Conestoga the same wagon? No. The Conestoga wagon was a much heavier wagon and often pulled by teams of up to six horses. Such wagons required reasonably good roads and were simply not practical for moving westward across the plains. The entire wagon was 26 feet long and 11 feet wide. The front wheels were 3 ½ feet high, rear wheels 4 to 4 ½ feet high. The empty wagon weighed 3000 to 3500 lbs. The Prairie schooner was the classic covered wagon that carried settlers westward across the North American plains. It was a lighter wagon designed to travel great distances on rough prairie trails. It stood 10-foot-tall, was 4 ft wide, and was 10 to 12 feet long, When the tongue and yoke were attached it was 23 feet long. The rear wheels were 50 inches in diameter and the front wheels 44 inches in diameter. -

Wagon Trains

Name: edHelper Wagon Trains When we think of the development of the United States, we can't help but think of those who traveled across the country to settle the great lands of the West. What were their travels like? What images come to your mind when you think of this great migration? The wagon train is probably one of those images. What exactly was a wagon train? It was a group of covered wagons, usually around 100 of them. These carried people and their supplies to the West before there was a transcontinental railroad. From 1837 to 1841, many people were in frustrating economic situations. Farmers, businessmen, and fur traders were looking for new opportunities. They hoped for a better climate, good crops, and better conditions. They decided to travel to the West. Missionaries wanted to convert American Indians to Christianity. They decided to head to the West. Why would these groups head out together? First of all, the amount of traveling was incredible. Much of the country they were traveling through was not settled and was difficult to travel. The trip could be confusing because of other trails made by Indians and buffalos. To get there safely, they went together. Second of all, there was a real danger that a wagon would be attacked by Native Americans. In order to have protection, it made sense to travel together. Wagon trains were very organized. People signed up to join one. There was a contract that stated the goals of the group's trip, terms to join, rules, and the details for electing officers. -

Taking Covered Wagons East a New Innovation Theory for Energy and Other Established Technology Sectors

William B. Bonvillian and Charles Weiss Taking Covered Wagons East A New Innovation Theory for Energy and Other Established Technology Sectors Frederick Jackson Turner, historian of the American frontier, argued that the always-beckoning frontier was the crucible shaping American society.1 He retold an old story, arguing that it defined our cultural landscape: when American settlers faced frustration and felt opportunities were limited, they could climb into covered wagons, push on over the next mountain chain, and open a new frontier. Even after the frontier officially closed in 1890, the nation retained more physical and social mobility than other societies. While historians debate the importance of Turner’s thesis, they still respect it. The American bent for technological advance shows a similar pattern. Typically, we find new technologies and turn them into innovations that open up new unoccupied territories—we take “covered wagon” technologies into new tech- nology frontiers. Information technology is an example. Before computing arrived, there was nothing comparable: there were no mainframes, desktops, or Internet before we embarked on this innovation wave. IT landed in a relatively open technological frontier. This has been an important capability for the U.S. growth economics has made it clear that technological and related innovation is the predominant factor driv- ing of growth.2 The ability to land in new technological open fields has enabled the U.S. economy to dominate every major Kondratiev wave of worldwide innovation William B. Bonvillian directs MIT’s Washington office and was a Senior Adviser in the U.S. Senate. He teaches innovation policy on the Adjunct Faculty at Georgetown University. -

The Struggle of Becoming Established in a Deprived Inner-City Neighbourhood David May NOTA DI LAVORO 101.2003

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics The Struggle of Becoming Established in a Deprived Inner-City Neighbourhood David May NOTA DI LAVORO 101.2003 NOVEMBER 2003 KNOW – Knowledge, Technology, Human Capital David May, Aalborg University, Aalborg Ø This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Note di Lavoro Series Index: http://www.feem.it/web/activ/_wp.html Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=XXXXXX The opinions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the position of Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei The special issue on Economic Growth and Innovation in Multicultural Environments (ENGIME) collects a selection of papers presented at the multidisciplinary workshops organised by the ENGIME Network. The ENGIME workshops address the complex relationships between economic growth, innovation and diversity, in the attempt to define the conditions (policy, institutional, regulatory) under which European diversities can promote innovation and economic growth. This batch of papers has been presented at the third ENGIME workshop: Social dynamics and conflicts in multicultural cities. ENGIME is financed by the European Commission, Fifth RTD Framework Programme, Key Action Improving Socio-Economic Knowledge Base, and it is co-ordinated by Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM). Further information is available at www.feem.it/engime. Workshops • Mapping Diversity Leuven, -

The Future of Polish – Ukrainian Relations

The Future of Polish – Ukrainian Relations Piotr Naimski Higher School of Business-National Louis University, Nowy S¹cz Speaking about the future gives me a certain freedom, a possibility to speculate, get carried away with one’s imagination. In order to do so, however, one should first start with a brief description of the present. During the last decade of the 20th century, Poland and Ukraine found themselves a part of Senior British Diplomat Robert Cooper’s post-colonial chaos. Although Cooper usually makes reference to the post-colonial territories of Africa, the Pacific region and Asia, this term might just as successfully describe the post-Soviet Eastern-Central Europe. There is a wide spectrum of possibilities, beginning with the former East Germany, which was externally overtaken by the Bonn-based Republic, thus joining the Fatherland of Germany. Moving further, one encounters the states as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, all facing difficulties, yet still having distinct successes to show for. When these three joined NATO in 1999, it was an undisputable turning point, as well as actual proof of the establishing ties forming with the ‘normality’ of the West. However, there are also critical cases that might qualify for the ‘failed states’ category. How else would one describe the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina or Kosovo? And yet somewhere in-between, one finds other Balkan states that are struggling to surpass the crisis. The spectrum also has place to encompass states created with the collapse of the Soviet empire, particularly the ones that were directly incorporated. Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova – the Brussels-based Europeans, with a typical dose of political correctness, and perhaps sarcasm as well, would come to refer to those as the Newly Independent States (NIS). -

PARS PRO TOTO.Qxd

Goran Tren~ovski PARS PRO TOTO Izdava ULIS DOOEL & Skopje Direktor Serjo`a Nedelkoski Likovno-grafi~ki dizajn ULIS DOOEL Pe~at †Van Gog# & Skopje CIP & Katalogizacija vo publikacija Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka †Sv. Kliment Ohridski#, Skopje 791.43(049.3) TREN^OVSKI, Goran Pars pro toto : Studija za kratkiot film i drugi tekstovi / Goran Tren~ovski. - Skopje : Ulis, 2008. - 156 str. : ilustr. ; 20 sm Fusnoti kon tekstot. - Bele{ka za avtorot: str. 155. - Bibliografija: str. 30-33 ISBN 978-9989-2699-4-3 a) Film - Esei © Site prava na izdanieto gi ima Ulis DOOEL & Skopje. Zabraneto e kopi- rawe, umno`uvawe i objavuvawe na delovi ili celoto izdanie vo pe~ateni ili vo elektronski mediumi bez pismeno odobrenie na izdava~ot ili avtorot. Izdanieto e finansiski pomognato od Ministerstvoto za kultura na Republika Makedonija Studija za kratkiot film i drugi tekstovi ULIS, 2008 Sodr`ina I. EDNO, KRATKO, CELO . 7 Pars pro toto . 9 II. BISTREWE MED-I-UM . 35 Pred i potoa . 37 Akterionstvo . 40 Napi{ano so kamera. 44 Novo i staro . 49 ^evli . 53 @ivot i anti`ivot . 57 ^eli~nata Leni . 61 Tri pogleda kon moralnosta . 66 Poetska vizura na turskiot del od svetot. 71 Integrirawe vo dokumentarnata mapa . 78 Stari yvezdi na novo platno . 82 Velikata skromnost kako metafora . 87 Vpe~atlivata prirodnost na stilot . 91 Bezgrani~nite vidici na Asterfest . 101 Strumica 1918. 103 Alijansa vo kinemati~kiot Tiveriopol. 116 Macedonian documentary circle. 121 I. EDNO, KRATKO, CELO PARS PRO TOTO 9 PARS PRO TOTO STUDIJA ZA KRATKIOT FILM Pars pro toto (pars pro toto) e osnovniot metod za filmsko pretvorawe na ne{tata vo znaci.