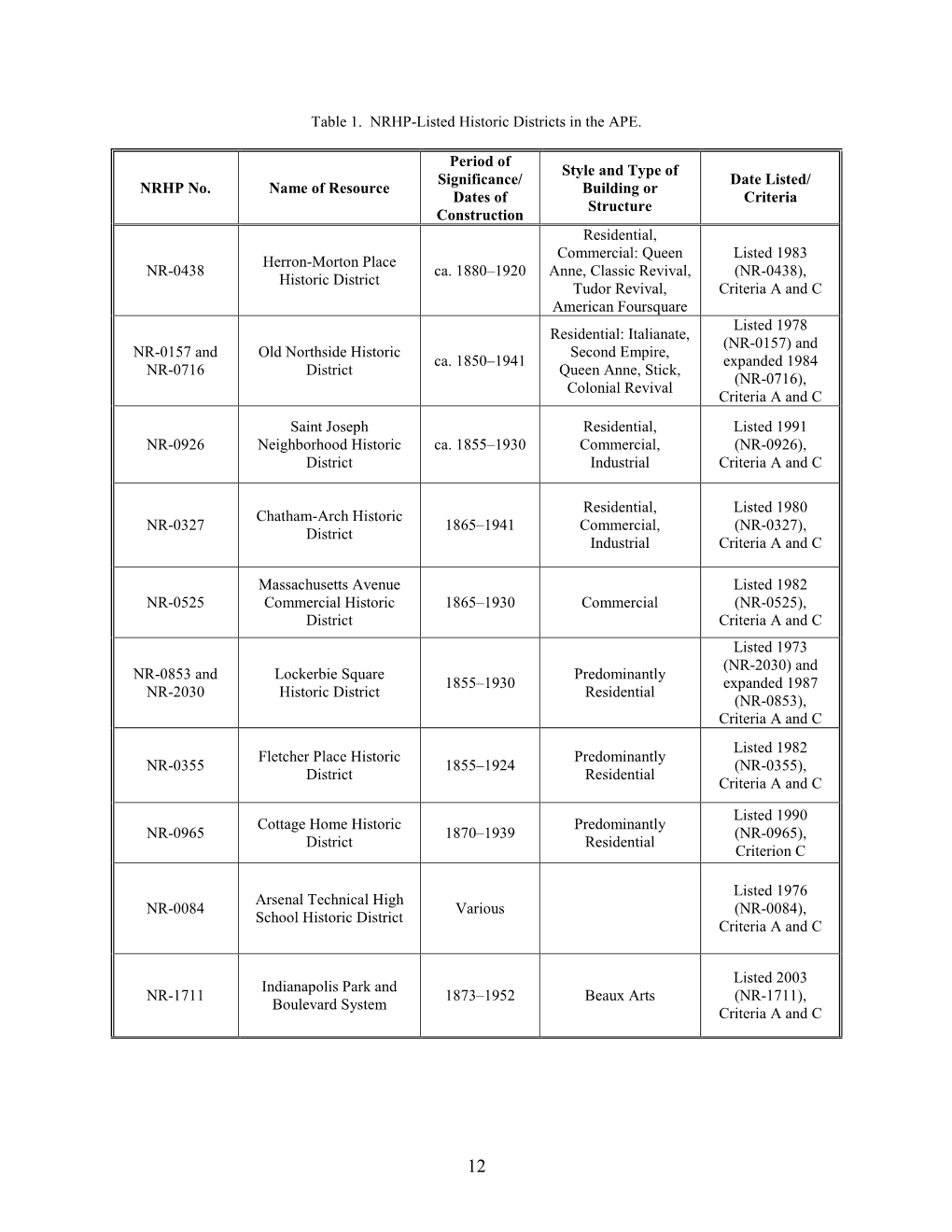

Tables and Historic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crown Hill Cemetery Notables - Sorted by Last Name

CROWN HILL CEMETERY NOTABLES - SORTED BY LAST NAME Most of these notables are included on one of our historic tours, as indicated below. Name Lot Section Monument Marker Dates Tour Claim to Fame Achey, David (Dad, see p 440) 7 5 N N 1838-1861 Skeletons Gambler who met his “just end” when murdered Achey, John 7 5 N N 1840-1879 Skeletons Gambler who was hung for murder Adams, Alice Vonnegut 453 66 Y 1917-1958 Authors Kurt Vonnegut’s sister Adams, Justus (more) 115 36 Y Y 1841-1904 Politician Speaker of Indiana House of Rep. Allison, James (mansion) 2 23 Y Y 1872-1928 Auto Allison Engineering, co-founder of IMS Amick, George 723 235 Y 1924-1959 Auto 2nd place 1958 500, died at Daytona Armentrout, Lt. Com. George 12 12 Y 1822-1875 Civil War Naval Lt., marble anchor on monument Armstrong, John 10 5 Y Y 1811-1902 Founders Had farm across Michigan road Artis, Lionel 1525 98 Y 1895-1971 African American Manager of Lockfield Gardens 1937-69 Aufderheide’s Family, May 107 42 Y Y 1888-1972 Musician She wrote ragtime in early 1900s (her music) Ayres, Lyman S 19 11 Y Y 1824-1896 Names/Heritage Founder of department stores Bacon, Hiram 43 3 Y 1801-1881 Heritage Underground RR stop in Indpls Bagby, Robert Bruce 143 27 N 1847-1903 African American Ex-slave, principal, newspaper publisher Baker, Cannonball 150 60 Y Y 1882-1960 Auto Set many cross-country speed records Baker, Emma 822 37 Y 1885-1934 African American City’s first black female police 1918 Baker, Jason 1708 97 Y 1976-2001 Heroes Marion County Deputy killed in line of duty Baldwin, Robert “Tiny” 11 41 Y 1904-1959 African American Negro Nat’l League 1920s Ball, Randall 745 96 Y 1891-1945 Heroes Fireman died on duty Ballard, Granville Mellen 30 42 Y 1833-1926 Authors Poet, at CHC ded. -

PX Call for Offers Dec 2020.Indd

11,075 SF BUILDING FOR SALE CALL FOR OFFERS: “PX BUILDING” ORIGINAL OFFICER’S QUARTERS AT HISTORIC FORT BEN 5745 Lawton Loop East Drive The Fort Harrison Reuse Authority (FHRA) is excited to announce that the PX building is now available for sale and redevelopment for a creative reuse project that is sensitive to the historic surroundings - including offi ce, retail, restaurant or other allowed use. Located in the historical Lawton Loop district of “Fort Ben,” the PX building was originally built in 1908 as the Fort Benjamin Harrison Army Base PX (Post Exchange store) and featured a basement gymnasium for soldiers. Later, when a new PX was built, the building was converted to a non- 5745 Lawton Loop East Drive on 0.8-acres commissioned offi cers club. Today it is a brick and beam historic shell waiting for a new life. LAST OPPORTUNITY TO OWN A PIECE OF FORT BEN HISTORY! Since the base closure, the former military post has become a vibrant residential, offi ce, retail and business campus that is widely recognized as a model for reuse and redevelopment of a former military installation. Fort Ben continues to grow and is nearing its fi nal leg in its redevelopment journey - with less than 20-acres available. The PX is the fi nal historic building owned by the FHRA available for reuse. Fort Ben Campus • Tax Increment Finance (TIF) District and federal Opportunity Zone • New city center for Lawrence, IN only 20 minutes northeast of downtown Indianapolis • Walkable, green campus with abundant on-street parking central to major employee hubs • 2020 -

Medical Mobilization and the War and Later at Other Depots and Camps

the arm, or vasomotor or vasa vasorum disturbances at the government prices. Samples of cloths with the issue prices will be kept on hand by all camp, cantonment and post quartermasters and to modified nutritional conditions in the wall may be examined by officers on request after the date mentioned. For leading the present stock will be carried at the following depots only, but this of the vessel. Halsted is inclined to reject these list will be extended from time to time as cloth becomes available: New York depot, Washington depot, Atlanta depot, Sam Houston explanations. He believes that what he describes as depot, San Francisco depot, Chicago depot, St. Louis depot. the abnormal, of the blood in the 3. The quartermaster general will determine by thorough investiga¬ whirlpool-like play tion a schedule of fair prices for making uniforms, including all neces¬ relatively dead pocket just below the site of the con¬ sary trimmings, linings, etc., but not including the cloths, and prepare a list of responsible tailors who agree to make uniforms for officers striction, and the lowered pulse pressure may be the at the schedule rates, the quartermaster general guaranteeing to the chief in tailors the collection of bills for all uniforms ordered through the repre¬ factors concerned the production of the dilata¬ sentatives of the quartermaster general. The schedule of prices, the tion. The of this conclusion must be estab¬ list of tailors agreeing to make uniforms at these prices and the regula¬ validity tions governing the sale to officers of the standard cloths, the placing lished before a rational method of cure can be insti¬ of orders, the acceptance of uniforms ordered and the payment of bills will then be published to the service. -

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: a Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick 334 N. Senate Avenue, Suite 300 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick March 2015 15-C02 Authors List of Tables .......................................................................................................................... iii Jessica Majors List of Maps ............................................................................................................................ iii Graduate Assistant List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv IU Public Policy Institute Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Key findings ....................................................................................................................... 1 Sue Burow An eye on the future .......................................................................................................... 2 Senior Policy Analyst Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 IU Public Policy Institute Background ....................................................................................................................... 3 Measuring the Use of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene -

SPRING 2020, Vol. 34, Issue 1 SPRING 2020 1

SPRING 2020, Vol. 34, Issue 1 SPRING 2020 1 MISSION NAWJ’s mission is to promote the judicial role of protecting the rights of individuals under the rule of law through strong, committed, diverse judicial leadership; fairness and equality in the courts; and ON THE COVER 19 Channeling Sugar equal access to justice. Innovative Efforts to Improve Access to Justice through Global Judicial Leadership 21 Learning Lessons from Midyear Meeting in New Orleans addresses Tough Cases BOARD OF DIRECTORS ongoing challenges facing access to justice. Story on page 14 24 Life After the Bench: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Honorable Sharon Mettler PRESIDENT 2 President's Message Hon. Bernadette D'Souza 26 Trial Advocacy Training for Parish of Orleans Civil District Court, Louisiana 2 Interim Executive Director's Women by Women Message PRESIDENT-ELECT 29 District News Hon. Karen Donohue 3 VP of Publications Message King County Superior Court, Seattle, Washington 51 District Directors & Committees 4 Q&A with Judge Ann Breen-Greco VICE PRESIDENT, DISTRICTS Co-Chair Human Trafficking 52 Sponsors Hon. Elizabeth A. White Committee Superior Court of California, Los Angeles County 54 New Members 5 Independent Immigration Courts VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLICATIONS Hon. Heidi Pasichow 7 Resource Board Profile Superior Court of the District of Columbia Cathy Winter-Palmer SECRETARY Hon. Orlinda Naranjo (ret.) 8 Global Judicial Leadership 419th District Court of Texas, Austin Doing the Impossible: NAWJ work with the Pan-American TREASURER Commission of Judges on Social Hon. Elizabeth K. Lee Rights Superior Court of California, San Mateo County IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT 11 Global Judicial Leadership Hon. Tamila E. -

50 Properties Listed in Or Determined Eligible for the NRHP Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6

Properties Listed In or Determined Eligible for the NRHP Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 (NR-2410; IHSSI # 098-296-01173), 1801 Nowland Avenue The Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 was listed in the NRHP in 2016 under Criteria A and C in the areas of Architecture and Education for its significance as a Carnegie Library (Figure 4, Sheet 8; Table 20; Photo 43). Constructed in 1911–1912, the building consists of a two-story central block with one-story wings and displays elements of the Italian Renaissance Revival and Craftsman styles. The building retains a high level of integrity, and no change in its NRHP-listed status is recommended. Photo 43. Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 (NR-2410; IHSSI # 098-296-01173), 1801 Nowland Avenue. Prosser House (NR-0090; IHSSI # 098-296-01219), 1454 E. 10th Street The Prosser House was listed in the NRHP in 1975 under Criterion C in the areas of Architecture and Art (Figure 4, Sheet 8; Table 20; Photo 44). The one-and-one-half-story cross- plan house was built in 1886. The original owner was a decorative plaster worker who installed 50 elaborate plaster decoration throughout the interior of the house. The house retains a high level of integrity, and no change to its NRHP-listed status is recommended. Photo 44. Prosser House (NR-0090; IHSSI # 098-296-01219), 1454 E. 10th Street. Wyndham (NR-0616.33; IHSSI # 098-296-01367), 1040 N. Delaware Street The Wyndham apartment building was listed in the NRHP in 1983 as part of the Apartments and Flats of Downtown Indianapolis Thematic Resources nomination under Criteria A and C in the areas of Architecture, Commerce, Engineering, and Community Planning and Development (Figure 4, Sheet 1; Table 20; Photo 45). -

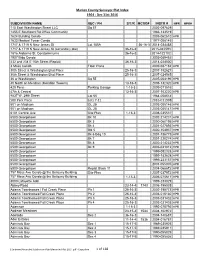

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave -

ORGANIZED CHARITY and the CIVIC IDEAL in INDIANAPOLIS 1879-1922 Katherine E. Badertscher Submitted to the Faculty of the Univers

ORGANIZED CHARITY AND THE CIVIC IDEAL IN INDIANAPOLIS 1879-1922 Katherine E. Badertscher Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Indiana University May 2015 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Dwight F. Burlingame, Ph.D., Chair Doctoral Committee ______________________________ Robert G. Barrows, Ph.D. March 6, 2015 ______________________________ Nancy Marie Robertson, Ph.D. ______________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgments My thanks begin with my doctoral committee. Dwight Burlingame advised me throughout my entire program, chose the perfect readings for me in our dissertation seminar, helped me shape the project, and read each chapter promptly and thoughtfully. His steadfast belief in my scholarship and his infinite kindness have been invaluable. Phil Scarpino and Bob Barrows led the seminars during which my dissertation idea took shape. Nancy Robertson challenged me to look at the work from many different angles and suggested a veritable treasure trove of scholarship upon which to draw. All their questions, comments, guidance, and encouragement have helped my work more than mere words can express. My colleagues in the doctoral program and students in the undergraduate program provided unwavering support as I lovingly talked about my research, “my organization,” and “my time period.” I especially thank Barbara Duffy, who chose the Charity Organization Society of Indianapolis (1879-1883) for her History of Philanthropy doctoral seminar research project. I enjoyed talking about “our women,” sharing our emerging ideas, swapping sources, and basking in one another’s “Eureka!” moments as we made one connection after another. -

Appendix A1 Copy of Master Dataset 1

1 Copy of Master Dataset Date Title Citation Street # Appendix5/3/08 A1 None None 5/10/08 None None 5/17/08 None None 5/24/08 None None 5/31/08 None None 6/7/08 None None 6/14/08 None None 6/21/08 None None 6/28/08 None None 7/5/08 None None 7/12/08 None None 7/19/08 None None 7/26/08 None None 9/6/08 None Plan Advert 9/13/08 None Plan Advert 1 9/20/08 None None 9/27/08 None None 10/4/08 None None 10/11/08 None None 10/18/08 None Plan Advert 10/25/08 None None 11/1/08 None None 11/8/08 None None 11/15/08 None None 11/22/08 None None 11/29/08 None None 5/2/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_May_2_1909_.pdf 4001 5/9/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_May_9_1909_.pdf 2823 5/16/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_May_16_1909_.pdf 45 5/23/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_May_23_1909_.pdf 3620 5/30/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_May_30_1909_.pdf 3121 6/6/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jun_6_1909_.pdf 2809 6/13/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jun_13_1909_.pdf 3339 6/20/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jun_20_1909_.pdf 5442 Copy of Master 6/27/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jun_27_1909_.pdf 3806 7/4/09 Dataset How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jul_4_1909_.pdf 1405 7/11/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jul_11__1909_.pdf 1306 7/18/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun_Jul_18__1909_.pdf 5404 7/25/09 How Others Have Built The_Indianapolis_Star_Sun__Jul_25__1909_.pdf -

Fort Benjamin Harrison: from Military Base to Indiana State

FORT BENJAMIN HARRISON: FROM MILITARY BASE TO INDIANA STATE PARK Melanie Barbara Hankins Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University April 2020 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D., Chair ____________________________________ Rebecca K. Shrum, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Anita Morgan, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements During my second semester at IUPUI, I decided to escape the city for the day and explore the state park, Fort Benjamin Harrison State Park. I knew very little about the park’s history and that it was vaguely connected to the American military. I would visit Fort Harrison State Park many times the following summer, taking hikes with my dog Louie while contemplating the potential public history projects at Fort Harrison State Park. Despite a false start with a previous thesis topic, my hikes at Fort Harrison State Park inspired me to take a closer look at the park’s history, which eventually became this project. Finishing this thesis would have been nearly impossible without the encouragement and dedication of many people. First, I need to thank my committee: Dr. Philip Scarpino, Dr. Rebecca Shrum, and Dr. Anita Morgan for their criticism, support, and dedication throughout my writing process. I would especially like to thank my chair, Dr. Scarpino for his guidance through the transition of changing my thesis topic so late in the game. -

Special Free

PAGE 2 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES JAN. 2, 193 PAY DEBTS OF BOOZE IS GIVEN SAD FAREWELL LEISURE CLUBS GIVE HER THIS HAND AND SHE’LL BE HAPPY' SOUTH WILL BE NEW SCHEDULE BRITISH PLEA Dazed Nation Conducts Rites Over John Barleycorn IS ANNOUNCED Th lams durk rnn*rx, xfitr iber'x dreixirf.dnl*ir(, if informal, wetwot referen- dum. i ronxiderin* action on the first rlear-rutir-rut nationalnational expressionexprexxlnn xinresince thethr , Defaulted Loans to Eight piasuer issue of ho. when or if the plain 1 rilfirncitiren mav quench himselfhimxelf alro-aUo- Various Groups Will ( preiedent holicallv arose hark in the IfttQ's. What to. expect?r\ prri ’ Consulting;onMi.tin* pavtpast precedent, Resume ~~ we ma look for more agitation, propaganda,ila and political turmoil overo\er one of ! States to Be Aired Again the easily social Activities After Halt for most simplified of problems.n> if , The Volstead art mav be swep away; thethr national honr-rtrvbone-dry prohibition Soon. amendment repealed, but rum, as u seeminglyinghi irrrcpressibleirrreprex*ible issue,ixxur. bidsbid* fairfair toto JBf Axltif Christmas. rema in. BY WILLIAM SIMMS I.EISI RF HOt R CALENDAR PHILIP In any event, the people manifestly ares*re on the wav toward anew phasephxxe In Scrlppt-Howard Editor MONDAY Forrl*n their political relationship with strop* beveragesbrirragr* afteraf.rr twelveluel'e vrjnyears of an rx-ex- sfr&S \ and Ohio. WASHINGTON. Jan. 2.—A vig- periment onre regarded as noble, sensible • and asa fixedfixed asa thethr starsxtarx in thrirtheir Delaware 21'i East Ohio rourses. What of the incredible twelve years—thear—the Vplsteadian\i;Meadian reign,reign thethe riserise ofof- street. -

F 521 148 Vol 16

'BLICATION OF THE INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY • F- 521 - 148- VOL 16- N02 INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES SARAH EVANS BARKER, Indianapolis f\.liCHAEI A. BucKMAN. Indianapolis, Second Vice Chajr MARY ANN BRADLFY, Indianapolis EDWARD E. BREEN, f\·farion, First Vice Chair DIANNEJ. C.'\RT).JI::L, Brown'ilOWll PATRICIA D. CURRAN, Indianapolis EDGAR CLtNN o,wrs, Indianapolis DANIEL M. EN'"I, lndiHnapolis RJCIIARD D. fELDMAN, Indianapolis RJCIIARD E. FORD, Wabash R. R-wI I AWKINS, Cannel THO�IA5 G. HOBACK, Indianapolis, Secretary lVlARTIN LAK•:, Marion LARRY S. LU'IOJS,Indianapolis POLLYjON TZ LENNON, Indianapolis jAMES H. MADISON, Bloomington MARYj ANE MEE.KER, Carmel ANUR£W \V. NICKLE, South Bend GEORC:F F. RAPP, Indianapolis BONNIE A. REILLY, indianapolis £VALINE H. RHODEHAMI�L, Indianapolis l.r\N M. ROLLAND, Fort \r\'ayne, Chair jAMES C. SHOOKJR., Indianapolis P. R. SwEENEY, Vincennes, Treasurer RoBERT B. ToOTHAKER, SouLh Bend W!LI.IA·'I I-f. \oVJC,GINS jR., Bloomington ADMINISTRATION SAI.VAJ'ORE G. Cn.ELLAJR., President RAY\·IOND L. SHOEMAKER, Executive Vice President At'\/NAHELLhj. JACKSON, Controller SuSAN P. BROWN, Senior Director, Human Resources STEPHEN 1. Cox, Vice President, Collections, Conservation, and Public Programs TIIOl\IAS A. MASON, Vice President, IHS Press BRENDA MYERS, Vice President, Marketing and Public Relations LINDA L. PRATI, Vice President, Development and Membership DARA BROOKS, Director, Membership CAROLYN S. SMJTII, Membership Coordinator TRACES OF INDIANA AND MIDWESTERN HISTORY RAY E. BOOMHOWER, Managing Editor GEORGE R. H.A.'\'LIN, Assiswnt Editor CONTRIBUTING EDITORS M. TEI<ESA BAER KATHLEEN M. BREEN DOUGU\S E. ClANIN WHAT'S NEXT? PAULA].