University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of States Parties Distr.: General 14 June 2017 English Original: English/French/Spanish

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea SPLOS /INF/31 Meeting of States Parties Distr.: General 14 June 2017 English Original: English/French/Spanish my anam r Twenty-seventh Meeting New York, 12 to 16 June 2017 List of Delegations Liste de Délégations Lista de Delegaciones SPLOS/INF/31 Albania Representatives H.E. Mrs. Besiana Kadare, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative to the United Nations ( Chair of the delegation ) Mr. Arben Idrizi, Minister Counsellor, Permanent Mission Mrs. Ingrid Prizreni, First Secretary, Permanent Mission Algeria Representatives H.E. Mr. Sabri Boukadoum, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative to the United Nations ( Chair of the delegation ) H.E. Mr. Mohammed Bessedik, Ambassador, Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations Mr. Mehdi Remaoun, First Secretary, Permanent Mission Angola Representatives H.E. Mr. Ismael Gaspar Martins, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative to the United Nations ( Chair of the delegation ) Vice-Admiral Martinho Francisco António, Technical Coordinator, Inter-Ministerial Commission of Delimitation and Maritime Demarcation of Angola Mrs. Anisabel Verissimo da Costa, Director of the International Exchange Directorate, Ministry of Justice and Human Rights Mrs. Claudete de Sousa, Director, Legal Office of the Ministry of Fisheries Mr. Marió Von Haff, Head, United Nations Department, Multilateral Affairs Directorate, Ministry of External Relations Col. Mário Simão, Military Counsellor, Permanent Mission Mr. Miguel Dialamicua, Counsellor, Permanent Mission Mrs. Vezua Paiva, Second Secretary, Permanent Mission Eng. José Januário da Conceição, Expert, Geographic and Cartographic Institute of Angola Eng. Lúmen Sebastião, Sonangol Expert Eng. Domingos de Carvalho Viana Moreira, Expert, Inter-Ministerial Commission of Delimitation and Maritime Demarcation Mr. -

D Tel: (260-1) 250800/254417 P.O

n •-*•—*-r .?-• «i Office of th UN Common Premises Alick Nkhata Road Tel: (260-1) 250800/254417 P.O. Box 31966 Fax: (260-1)253805/251201 Lusaka, Zambia E-mail: [email protected] D «f s APR - I 2003 bv-oSHli i EX-CUilVtMtt-I'Jt To: Iqbal Riza L \'. •^.ISECRETAR^-GEN Chef de Cabinet Office of the Secretary General Fax (212) 963 2155 Through: Mr. Mark MallochBrown UNDGO, Chair Attn: Ms. Sally Fegan-Wyles Director UNDGO Fax (212) 906 3609 Cc: Nicole Deutsch Nicole.DeutschfaUJNDP.oru Cc: Professor Ibrahim Gambari Special Advisor on Africa and Undersecretary General United N£ From: Olub^ Resident Coordinator Date: 4th Febraaiy 2003 Subject: Zambia UN House Inauguration Reference is made to the above-mentioned subject. On behalf of the UNCT in Zambia, I would like to thank you for making available to us, the UN Under Secrets Specia] Advisor to Africa, Professor Gambari, who played a critical role in inauguration oftheUN House. We would also like to thank the Speechwriting Unit, Executive Office of the Secretary-General for providing the message Jrom the Secretary General that Professor Gambari gave on his behalf. The UNCT_took advantage of his_ presence and_ asked .him.. to also launch the Dag Hammarskjold Chair of Peace, Human Rights and Conflict Management, which is part of to conflict prevention in the sub region. The Inauguration of the UN House was a success, with the Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs; Honourable Newstead Zimba representing the Government while members of the Diplomatic Corps and Civil Society also attended this colourful and memorable occasion. -

UNN Post UTME Past Questions and Answers for Arts and Social Science

Get more news and educational resources at readnigerianetwork.com UNN Post UTME Past Questions and Answers for Arts and Social Science [Free Copy] Visit www.readnigerianetwork.com for more reliable Educational News, Resources and more readnigerianetwork.com - Ngeria's No. 1 Source for Reliable Educational News and Resources Dissemination Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com Get more latest educational news and resources @ www.readnigerianetwork.com Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com 10. When we woke up this morning, the sky ENGLISH 2005/2006 was overcast. A. cloudy ANSWERS [SECTION ONE] B. clear C. shiny 1. C 2. A 3. B 4. B 5. A 6. C 7. B 8. D 9. C D. brilliant 10. C 11. D 12. B 13. C 14. B 15. C 11. Enemies of progress covertly strife to undermine the efforts of this administration. A. secretly B. boldly C. consistently D. overtly In each of questions 12-15, fill the gap with the most appropriate option from the list following gap. 12. The boy is constantly under some that he is the best student in the class. A. elusion B. delusion C. illusion D. allusion 13. Her parents did not approve of her marriage two years ago because she has not reached her ______. A. maturity B. puberty C. majority D. minority 14. Our teacher ______ the importance of reading over our work before submission. A. emphasized on B. emphasized C. layed emphasis on D. put emphasis 15. Young men should not get mixed ______politics. A. in with B. up with C. up in D. on with 2 Get more latest educational news and resources @ www.readnigerianetwork.com Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com ENGLISH 2005/2006 QUESTIONS [SESSION 2] COMPREHENSION 3. -

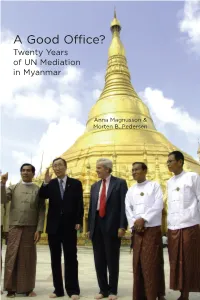

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

MB 29Th July 2019-V13.Cdr

RSITIE VE S C NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES COMMISSION NI O U M L M A I S N S O I I O T N A N T E HO IC UG ERV HT AND S MONDAA PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Y www.nuc.edu.ng Bulletin 0795-3089 5th August, 2019 Vol. 14 No. 30 Nigeria Must Elevate Education for its Survival - Prof Gambari ormer Minister of Foreign development that engaged the He condemned the practice Affairs and Ambassador e f f o r t s a n d a t t e n t i o n o f whereby students were trained only Ft o U n i t e d N a t i o n s , government and all segments of to be able to provide for their daily Professor Ibrahim Gambari, has the society. bread, while negating the holistic advised that with the present challenges confronting Nigeria, what was required for survival a n d c o m p e t i v e n e s s i n a globalising world was elevation of education as principal tool for p e a c e , c i t i z e n s h i p a n d entrepreneurship. This was contained in his Commencement lecture entitled “The place of university E d u c a t i o n i n G l o b a l Development” delivered at the 5 t h undergraduate and 1 s t postgraduate convocation ceremony of Adeleke University, Ede. Convocation Lecturer, Adeleke University, Prof. -

Major Research Paper Uhuru Kenyatta Vs. The

1 Major Research Paper Uhuru Kenyatta vs. The International Criminal Court: Narratives of Injustice & Solidarity Stefanie Hodgins Student Number: 5562223 Supervisor: Professor Rita Abrahamsen University of Ottawa Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Date: July 23rd, 2015 2 Abstract The intent of this paper is to explore the dominant narratives used by Uhuru Kenyatta to discredit the legitimacy of the International Criminal Court within Kenya and Africa. Using a framing analysis as a theoretical approach, this paper identified four primary arguments, which pertained to issues of neo-colonialism, sovereignty, ethnic polarization, and national reconciliation. This paper argues that these arguments supported narratives of injustice and solidarity and were evoked by Kenyatta in order to mobilize a domestic and regional support base throughout the course of his trial at The Hague. This paper examines how these narratives were used in the context of the 2013 Kenyan election and at Kenyatta's various appearances at the African Union. Overall, this analysis offers new insights into the effectiveness of global criminal justice and considers the importance of addressing local perceptions and realities. 3 Table of Contents 1.0 - Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 - Theoretical and Methodological Approach ..................................................................................... 7 3.0 - Kenya's 2007-08 Post-Election -

Making Power Sharing Work: Kenya's Grand Coalition Cabinet, 2008–2013

MAKING POWER SHARING WORK: KENYA’S GRAND COALITION CABINET, 2008–2013 SYNOPSIS Leon Schreiber drafted this case Following Kenya’s disputed 2007 presidential election, fighting based on interviews conducted in broke out between supporters of incumbent president Mwai Kibaki Nairobi, Kenya in September 2015. Case published March 2016. and opposition leader Raila Odinga. Triggered by the announcement that Kibaki had retained the presidency, the violence ultimately This series highlights the governance claimed more than 1,200 lives and displaced 350,000 people. A challenges inherent in power sharing February 2008 power-sharing agreement between the two leaders arrangements, profiles adaptations helped restore order, but finding a way to govern together in a new that eased these challenges, and unity cabinet posed a daunting challenge. Under the terms offers ideas about adaptations. negotiated, the country would have both a president and a prime minister until either the dissolution of parliament, a formal withdrawal by either party from the agreement, or the passage of a referendum on a new constitution. The agreement further stipulated that each party would have half the ministerial portfolios. Leaders from the cabinet secretariat and the new prime minister’s office worked to forge policy consensus, coordinate, and encourage ministries to focus on implementation. The leaders introduced a new interagency committee system, teamed ministers of one party with deputy ministers from the other, clarified practices for preparing policy documents, and introduced performance contracts. Independent monitoring, an internationally mediated dialogue to help resolve disputes, and avenues for back-channel communication encouraged compromise between the two sides and eased tensions when discord threatened to derail the work of the executive. -

ICC-01/09-02/11 Date: 23 March 2011 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER II Before

ICC-01/09-02/11-13 23-03-2011 1/7 CB PT Original: English No.: ICC‐01/09‐02/11 Date: 23 March 2011 PRE‐TRIAL CHAMBER II Before: Judge Ekaterina Trendafilova, Presiding Judge Judge Hans‐Peter Kaul, Judge Judge Cuno Tarfusser, Judge SITUATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF KENYA IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR v. FRANCIS KIRIMI MUTHAURA, UHURU MUIGAI KENYATTA AND MOHAMMED HUSSEIN ALI Public Document Defence Submissions on the Variation of Summons Conditions for Francis Kirimi Muthaura, Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta and Mohammed Hussein Ali Source: Defence No. ICC‐01/09‐02/11 1/7 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/7959a5/23 March 2011 ICC-01/09-02/11-13 23-03-2011 2/7 CB PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Mr. Luis Moreno‐Ocampo, Prosecutor Counsel for Francis Kirimi Muthaura: Ms. Fatou Bensouda, Deputy Prosecutor Karim Khan and Kennedy Ogetto Counsel for Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta: Steven Kay QC and Gillian Higgins Counsel for Mohammed Hussein Ali: Evans Monari and Gershom Otachi Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Ms. Silvana Arbia, Registrar Deputy Registrar Mr. Didier Daniel Preira, Deputy Registrar Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section No. ICC‐01/09‐02/11 2/7 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/7959a5/23 March 2011 ICC-01/09-02/11-13 23-03-2011 3/7 CB PT I. -

National Assembly

February 23, 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Tuesday, 23rd February, 2016 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR DISCHARGE OF MEMBERS FROM COMMITTEES Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, I want to encourage you to pay attention to what is happening. Hon. Members, I have this Communication from the Chair which is on discharge of Members from Committees. I wish to report to the House that I am in receipt of a letter dated 16th February 2016, from the Minority Party Whip notifying me that the CORD Coalition has discharged the following Members from Committees: (i) Hon. Khatib Mwashetani, MP, who is discharged from the Departmental Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. (ii) Hon. Salim Idd Mustafa, MP, who is discharged from the Departmental Committee on Labour and Social welfare and the Joint Committee on Parliamentary Broadcasting and Library. He is the Vice-Chairperson of the latter Committee. (iii) Hon. Gideon Mung’aro, MP, who is discharged from the Departmental Committee on Lands. Hon. Members, the letter which is written pursuant to the provisions of Standing Order No. 176 also intends to discharge Hon. Khatib Mwashetani, MP, from the House Business Committee (HBC) and the Budget and Appropriations Committee. However, it is a fact that the Member for Lungalunga Constituency is not a Member of the HBC which was constituted by this House on 9th February 2016. You are also aware that the Budget and Appropriations Committee is yet to be reconstituted. This, therefore, implies that the intended discharge of the Member for Lungalunga from these two Committees was inadvertent. -

Kenya: Impact of the ICC Proceedings

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°84 Nairobi/Brussels, 9 January 2012 Kenya: Impact of the ICC Proceedings convinced parliamentarians. Annan consequently transmit- I. OVERVIEW ted the sealed envelope and the evidence gathered by Waki to the ICC chief prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, on 9 Although the mayhem following the disputed December July 2009. Four months later, on 5 November 2009, the pro- 2007 elections seemed an exception, violence has been a secutor announced he intended to request authorisation to common feature of Kenya’s politics since the introduction proceed with an investigation to determine who bore of a multiparty system in 1991. Yet, the number of people greatest responsibility for crimes committed during the killed and displaced following that disputed vote was un- post-election violence. precedented. To provide justice to the victims, combat per- vasive political impunity and deter future violence, the In- When Moreno-Ocampo announced, on 15 December 2010, ternational Criminal Court (ICC) brought two cases against the names of the six suspects, many of the legislators who six suspects who allegedly bore the greatest responsibility had opposed the tribunal bill accused the court of selec- for the post-election violence. These cases have enormous tive justice. It appears many had voted against a Kenyan political consequences for both the 2012 elections and the tribunal on the assumption the process in The Hague would country’s stability. During the course of the year, rulings be longer and more drawn out, enabling the suspects with and procedures will inevitably either lower or increase com- presidential ambitions to participate in the 2012 election. -

High Commissioner's Strategic Management Plan 2010-2011

High Commissioner’s Strategic Management Plan 2010-2011 High Commissioner’s Strategic Management Plan 2010-2011 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mission Statement The mission of the Office of the United Nations High General Assembly in resolution 48/141, the Charter Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is to work of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of for the promotion and protection of all human rights Human Rights and subsequent human rights for all people; to help empower people to realize instruments, the 1993 Vienna Declaration and their rights and to assist those responsible for Programme of Action, and the 2005 World Summit upholding such rights in ensuring that they are Outcome Document. implemented. In carrying out its mission OHCHR will: u Give priority to addressing the most pressing Operationally, OHCHR works with governments, human rights violations, both acute and chronic, legislatures, courts, national institutions, civil society, particularly those that put life in imminent peril. regional and international organizations, and the u Focus attention on those who are at risk and United Nations system to develop and strengthen vulnerable on multiple fronts. capacity, particularly at the national level, for the u Pay equal attention to the realization of civil, promotion and protection of human rights in cultural, economic, political, and social rights, accordance with international norms. -

Special Focus

Fall/Winter 2014, Vol. XXVI No.3-4 Table of Contents SPECIAL FOCUS: 1 SPECIAL FOCUS Family Planning Policy: a case study of FAMILY PLANNING POLICY: China and India A CASE STUDY OF CHINA AND INDIA 5 HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENT The Implementation of Incineration for Waste Reduction Environmental Links to Breast Cancer Tackling the Fresh Water Crisis: a shared responsibility 12 FOOD FOR THOUGHT Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns 14 MORE FOOD FOR THOUGHT Implementing Renewable Sources of Energy in Developing Countries 16 DID YOU KNOW? Carbon Emissions: how the world’s worst offenders are making a change Granite Walls of Grand Central Station 17 GOOD NEWS Increase of Tiger Population in Nepal Approved Leukemia Drug: makes waves in cancer research KWIBUKA 20: remember. reunite. renew. Children are Finally Eating their: fruits and vegetables Panthera Programme Makes Strides to: save indigenous lives in ghana SOURCE: www.Census.Gov, 2012 19 MORE DID YOU KNOW? World Food Supply at Risk CHINA AND INDIA POPULATION GROWTH 19 VOICES 2026: CHINA GROWTH PEAKS AND INDIA OVERTAKES AS 23rd International Conference on LARGEST POPULATION IN THE WORLD Health and Enviroment: GLOBAL PARTNERS FOR GOBAL SOLUTIONS UN DPI/NGO Conference The linkages between contraception, climate change and human popula- UN General Assembly 69th Session tion with the environment are increasingly surfacing. From an era when such UN Climate Change Summit 2014 NY Climate Week discussions were disregarded during negotiations, they are now being met NERC Worshops in Environmental Science at Oxford University with interest. Finding evidence in reports, speeches and articles, synergies Nelson Mandela International Day 2014 between human health, population growth and the environment is gradually 22 POINT OF VIEW: approaching the status of a political priority.