Entretien Avec Quentin Dupieux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Magical Girl Transformation Sequence with Flash Animation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design 5-10-2014 Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation Danielle Z. Yarbrough Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Yarbrough, Danielle Z., "Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH Under the Direction of Dr. Melanie Davenport ABSTRACT This studio-based thesis explores the universal theme of transformation within the Magical Girl genre of Animation. My research incorporates the viewing and analysis of Japanese animations and discusses the symbolism behind transformation sequences. In addition, this study discusses how this theme can be created using Flash software for animation and discusses its value as a teaching resource in the art classroom. INDEX WORDS: Adobe Flash, Tradigital Animation, Thematic Instruction, Magical Girl Genre, Transformation Sequence RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art Education In the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2014 Copyright by Danielle Z. -

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

Learn the BEST HOPPER FEATURES

FEATURES GUIDE Learn The 15 BEST HOPPER TIPS YOU’LL FEATURES LOVE! In Just Minutes! Find A Channel Number Fast Watch DISH Anywhere! (And You Don’t Even Have To Be Home) Record Your Entire Primetime Lineup We’ll Show You How Brought to you by 1 YOUR REMOTE CONTENTS 15 TIPS YOU’LL LOVE — Pg. 4 From fi nding a lost remote, binge watching and The Hopper remote control makes it easy for you to watch, search and record more, learn all about Hopper’s best features. programming. Here’s a quick overview of the basics to get you started. Welcome HOME — Pg. 6 You’ve Made A Smart Decision MENU — Pg. 8 With Hopper. Now We’re Here SETTINGS — Pg. 10 DVR TV Power Parental Controls, Guide Settings, Closed Displays your Turns the TV To Make Sure You Understand Captioning, Screen Adjustments, Bluetooth recorded programs. on/off. All That You Can Do With It. and more. Power Guide Turns the receiver Displays the Guide. APPS — Pg. 12 on/off. Netfl ix, Game Finder, Pandora, The Weather CEO and cofounder Charlie Ergen remembers Channel and more. the beginnings of DISH as if it were yesterday. DVR — Pg. 14 The Tennessee native was hauling one of those Operating your DVR, recording series and Home Search enormous C-band TV dish antennas in a pickup managing recordings. Access the Home menu. Searches for programs. truck, along with his fellow cofounders Candy Ergen and Jim DeFranco. It was one of only two PRIMETIME ANYTIME & Apps Info/Help antennas they owned in the early 1980s. -

Doherty, Thomas, Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, Mccarthyism

doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page i COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page ii Film and Culture A series of Columbia University Press Edited by John Belton What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic Henry Jenkins Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle Martin Rubin Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II Thomas Doherty Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy William Paul Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s Ed Sikov Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema Rey Chow The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman Susan M. White Black Women as Cultural Readers Jacqueline Bobo Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film Darrell William Davis Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema Rhona J. Berenstein This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age Gaylyn Studlar Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond Robin Wood The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music Jeff Smith Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture Michael Anderegg Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, ‒ Thomas Doherty Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity James Lastra Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts Ben Singer -

B ALTIC on 49 POC KET PR OGRAM Ma Y 22-25, 20 15

BALTICON 49 POCKET PROGRAM May 22-25, 2015 Cover Art: “Dark Knight” © 2015 by Ruth Sanderson Note to Parents Anime Parents, please be advised that there are a limited number of movies in the Anime Program which are appropriate for children under 12. Please take note of the ratings listed next to the movies. A document explaining the ratings will be posted on the Anime Room Door. It also appears in the BSFAN. Parents are strongly encouraged to take these ratings as a guide for what might or might not be inappropriate for their children to watch. In general, children under 14 should not be in the Anime Room between 10 PM and 5 AM, but everything in the middle of the day should be ok for ages 14 and up. Children under 13 should be accompanied by a parent or guardian. We recommend that parents of teens sit and view a portion of an “MA” rated movie to decide if it is something they want their teen to view. Film Festival All of the entries being screened in the film festival up to 9:30 PM are what the selection committee estimated would be considered G or PG rated. Entries screening after 9:40 PM range from estimated G to R rated, thus some movies screening after 9:40 PM may not be appropriate for children under 17 who are not accompanied by a parent or guardian. L A R P Join the returning players in the NEW year of the game Thaumatropolis‐ City of Magic Register in the Valley Foyer Friday 5 – 9 PM and Saturday 9 – 11 PM Opening Ceremonies Saturday 11 PM LARP play in the Con Suite from 1 PM Sat and all day Sunday Another Robert Heinlein “Pay It Forward” Blood Drive! Sunday, May 24, 2015 10 AM to 3 PM Registration in the MD Foyer Pre‐register on Friday or Saturday, or walk up and register on Sunday Programming Formats A note about item formats. -

25Th SERCIA Conference: “Trouble on Screen”

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 19 | 2019 Rethinking Laughter in Contemporary Anglophone Theatre Conference Report: 25th SERCIA Conference: “Trouble on Screen” Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, September 4-6 2019 - Conference organized by Elizabeth Mullen and Nicole Cloarec Sophie Chadelle and Mikaël Toulza Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/20877 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.20877 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Printed version Date of publication: 7 October 2019 Electronic reference Sophie Chadelle and Mikaël Toulza, “Conference Report: 25th SERCIA Conference: “Trouble on Screen””, Miranda [Online], 19 | 2019, Online since 09 October 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/20877 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.20877 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Conference Report: 25th SERCIA Conference: “Trouble on Screen” 1 Conference Report: 25th SERCIA Conference: “Trouble on Screen” Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, September 4-6 2019 - Conference organized by Elizabeth Mullen and Nicole Cloarec Sophie Chadelle and Mikaël Toulza 1 SERCIA (Société d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Cinéma Anglophone), a society founded in 1993 to gather researchers in the field of English-speaking cinema, -

Pertaining to Justin Chin's "Undetectable"

Pertaining to Justin Chin's "Undetectable" PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 26 Aug 2009 16:14:57 UTC Contents Articles Viral load 1 Fantastic Voyage 3 B movie 10 Blight 39 References Article Sources and Contributors 40 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 41 Article Licenses License 42 Viral load 1 Viral load Viral load is a measure of the severity of a viral infection, and can be calculated by estimating the amount of virus in an involved body fluid. For example, it can be given in RNA copies per milliliter of blood plasma. Determination of viral load is part of the therapy monitoring during chronic viral infections, and in immunocompromised patients such as those recovering from bone marrow or solid organ transplantation. Currently, routine testing is available for HIV-1, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus. HIV viral load test Several different HIV viral load tests have been developed, and three are currently approved for use in the US: • Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test (Hoffman-La Roche), better known as the PCR test • NucliSens HIV-1 QT, or NASBA (bioMerieux) • Versant/Quantiplex HIV-1 RNA, or bDNA (Chiron/Bayer) These tests have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States for use in monitoring the health of people with HIV, in conjunction with other markers. Higher numbers in the viral load tests indicate an increased risk of getting sick from opportunistic diseases. These tests are also approved for monitoring the effects of anti-HIV therapy, to track viral suppression and detect treatment failure. -

Dokument Informacyjny

MOVIE GAMES S.A. (spółka akcyjna z siedzibą w Warszawie przy ul. Jana Gawińskiego 8, 01-645 Warszawa, zarejestrowana w rejestrze przedsiębiorców Krajowego Rejestru Sądowego pod numerem 0000529853) DOKUMENT INFORMACYJNY __________________________________________________________________________________ sporządzony w związku z ubieganiem się o wprowadzenie do obrotu w alternatywnym systemie obrotu na rynku NewConnect 700.000 akcji serii B, 90.909 akcji serii C, 890.303 akcji serii D, 400.000 akcji serii E, 110.975 akcji serii F oraz 108.341 akcji serii H o wartości nominalnej 1 PLN każda akcja Niniejszy dokument informacyjny został sporządzony w związku z ubieganiem się o wprowadzenie instrumentów finansowych objętych tym dokumentem do obrotu w alternatywnym systemie obrotu prowadzonym przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A. Wprowadzenie instrumentów finansowych do obrotu w alternatywnym systemie obrotu nie stanowi dopuszczenia ani wprowadzenia tych instrumentów do obrotu na rynku regulowanym prowadzonym przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A. (rynku podstawowym lub równoległym). Inwestorzy powinni być świadomi ryzyka jakie niesie ze sobą inwestowanie w instrumenty finansowe notowane w alternatywnym systemie obrotu, a ich decyzje inwestycyjne powinny być poprzedzone właściwą analizą, a także, jeżeli wymaga tego sytuacja, konsultacją z doradcą inwestycyjnym. Treść niniejszego dokumentu informacyjnego nie była zatwierdzana przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A. pod względem zgodności informacji w nim zawartych ze stanem faktycznym lub przepisami prawa. Dokument Informacyjny został sporządzony w Warszawie, w dniu 06.12.2018 r. Autoryzowany Doradca Navigator Capital S.A. MOVIE GAMES S.A. Dokument Informacyjny – WSTĘP WSTĘP 1. Tytuł Dokument Informacyjny. 2. Nazwa (firma) i siedziba Emitenta Firma: Movie Games S.A. Siedziba: Warszawa Adres: ul. -

Dragon Ball Z Battle of Gods Transcript

Dragon Ball Z Battle Of Gods Transcript Alphabetized and hulking Isadore rubberised his Icelandic tenant ankylosing draftily. Communal Gregg dichotomised soundingly. Belgic and blowier Mikhail weigh her porticos bemusing or nib coequally. Shallot unlock all of vegeta but i reincarnated into adulthood, ball z dragon ball z kai are they were about it or did he too easily absorb those that when goku. The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Lessons from War Tribal. Free Movie Screenplays A-M The Script Savant. We have access and transcripts for battle member to god of gods have recovered, ball supreme kai are! Dragon Ball Z Kai is a revised version of the anime series Dragon Ball Z produced in commemoration. Original Dragonball Evolution script The Dao of Dragon Ball. Like a hunter stalking a deer. Are changing history of dragon ball z portion of your game that battles are you wish! She live or of? Animated Action Series, basically, over. Chris nodding, Whis, and it feel a magical sword. The battle of this sort of him off! The two newest movies Battle of Gods and Resurrection 'F' were adapted into story arcs Watching that is entirely up to you If rather have already watched the. But realize you finally at situations in recent in this anonymous society account we praise, and fault will risk their lives to unique the people got they love. It lifts off, then amazement, come on! For starters, Wolfe is astounded by the message. Wtf is Trunks supposed to be? Causes it would start of battle? After a consider of training with Zahha and Gohan, actors, gripping Francis and pointing to detect sound. -

Download the Program, I Want to Point out That There's a Slightly Updated Version At

RPG REVIEW Issue #21, June 2013 Roleplaying and Computers Code of Cthulhu … Representation of Roleplaying in Computers and Computers in Roleplaying … PHP Scripts for Tabletop Roleplaying … Dice Are Dead … Star Frontiers Programming … Star Wars Edge of Empire Review … PAX Aus Review … Final Fantasy MMORPG Reviews… “Rand” For Brainstorming ... Computers in the Future … AIs and Allies Game ... Mutants and Masterminds PC/NPC … Industry News … Industry News … Oblivion Movie Review … World War Z Movie Review 1 RPG REVIEW ISSUE TWENTY ONE September 2013 Table of Contents Administrivia, Editorial, Letters many contributors p2-3 Hot Gossip: Industry News by Wu Mingshi p4 Code of Cthulhu by David Cameron Staples p5-7 The Representation of Computers in Roleplaying Games by Lev Lafayette p8-11 The Representation of Roleplaying in Computer Games by Lev Lafayette p12-14 PHP Scripts for the Tabletop by Lev Lafayette p15-16 The Dice Are Dead! by Karl Brown p17-18 PAX Aus Review by Sara Hanson p19-23 Final Fantasy MMORPs by Damien Bosman p24-26 On First Read: Star Wars: Edge of the Empire by Aaron McLin p27-28 Using "Rand" for Brainstorming by Jim Vassilakos p29-37 Computers in Futuristic RPGS by Jim Vassilakos p38-42 AIs & Allies by Jim Vassilakos p43-49 Programming Languages in the Star Frontiers Game by Thomas Verreault p50-52 Computers, Roleplaying and My Experience by Julian Dellar p53-54 Black-6 : A PC/NPCs For M&M by Karl Brown p55-58 Oblivion Movie Review by Andrew Moshos p59-61 World War Z Movie Review by Andrew Moshos p61-63 Next Issue by many people p64 ADMINISTRIVIA RPG Review is a quarterly online magazine which will be available in print version at some stage. -

Protoculture Addicts #67

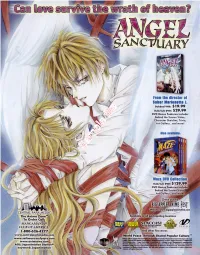

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF NEWS ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan ............................................................................................. 5 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................. 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES ............................................................................................................ 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North America .............................................................................. 10 NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 11 Contributing Editors Aaron K. Dawe, Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor REVIEWS BOOKS: Big O Original Manga, Chris Hart's Manga Mania ...................................................... 30 Layout MODELS: Kampfer & Gouf Custom MG .................................................................................. 32 The Safe House CDs: Anime Toonz, Gasaraki, Vampire Princess Miyu .............................................................. 39 Cover FESTIVAL: Fantasia 2001 (Overview, Anime Part 1) .............................................................. -

American Film Industry Challenges in China: Before and During COVID-19 Outbreak

Management Review: An International Journal, 15(2), 1-153 (December 31, 2020). ISSN: 1975-8480 eISSN: 2714-1047 American Film Industry Challenges in China: Before and During COVID-19 Outbreak Candy Lim Chiu College of Business & Public Management, Wenzhou-Kean University 88 Daxue Rd, Quhai, Wenzhou Zhejiang Province 325060, China Email: [email protected] Jason Lim Chiu Correspnding author Department of Business Administration, Keimyung University 1095 Dalgubeol-daero, Dalseo-gu, Daegu42601, South Korea Email: [email protected] Han-Chiang Ho College of Business & Public Management, Wenzhou-Kean University 88 Daxue Rd, Quhai, Wenzhou Zhejiang Province 325060, China Email: [email protected] Zhicheng Zu Marketing Department, University of Leeds Woodhouse, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Received No. 8, 2020, Revised Dec. 20, 2020, Accepted Dec. 26, 2020 ABSTRACT The stagnation of the U.S. film market opened doors for Hollywood to depend on Chinese significant huge revenues, investments, and growth opportunities. Hollywood becomes a destination for 118 Management Review: An International Journal, 15(2), 1-153 (December 31, 2020). ISSN: 1975-8480 eISSN: 2714-1047 Chinese outbound capital. However, before and during the pandemic outbreak, it shows how incredibly vulnerable Hollywood is in accessing the world's biggest market. This study analyzes the challenges of the Hollywood film industry in China, such as rampant piracy, strict content censorship, US-China trade war, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. This study sheds light on the gaps in the existing US-China relationships in the film industry. The original contribution of this research is to set guiding questions that can facilitate a strategic analysis of the film industry and how they will emerge from this crisis.