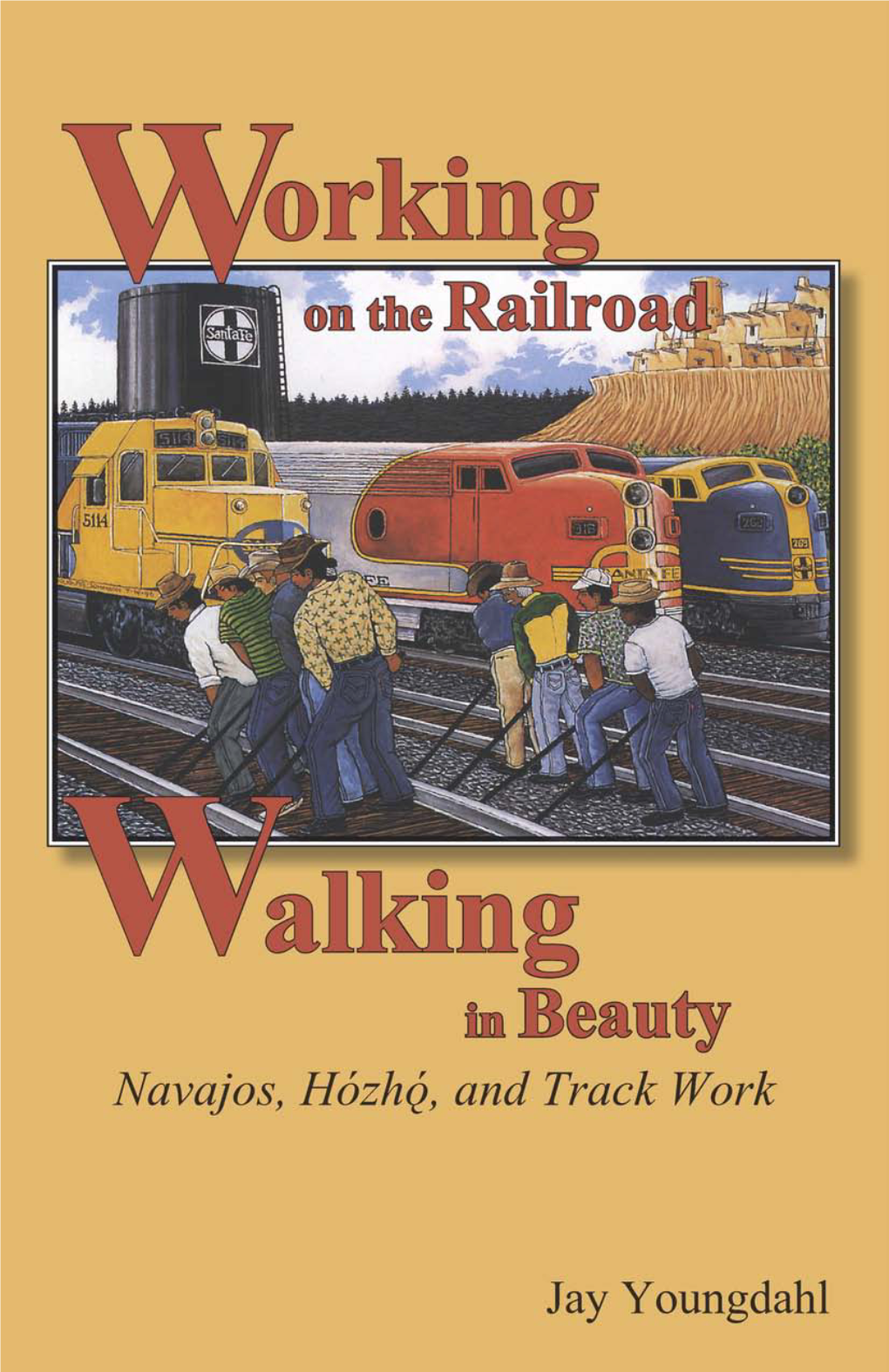

Working on the Railroad, Walking in Beauty: Navajos, Hózho, and Track

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Report

Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report fy2011 annual report 1 Contents Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report 4 Funds: fy2011 permanent fund, revenue and expenditures Cover photos, 6–7 A network of cultural coalitions fosters cultural participation clockwise from top left: Dancer Jonathan Krebs of BodyVox Dance; Vital collaborators – five statewide cultural agencies artist Scott Wayne 8–9 Indiana’s Horse Project on the streets of Portland; the Museum of 10–16 Cultural Development Grants Contemporary Craft, Portland; the historic Astoria Column. Oregonians drive culture Photographs by 19 Tatiana Wills. 20–39 Over 11,000 individuals contributed to the Trust in fy2011 oregon cultural trust board of directors Norm Smith, Chair, Roseburg Lyn Hennion, Vice Chair, Jacksonville Walter Frankel, Secretary/Treasurer, Corvallis Pamela Hulse Andrews, Bend Kathy Deggendorfer, Sisters Nick Fish, Portland Jon Kruse, Portland Heidi McBride, Portland Bob Speltz, Portland John Tess, Portland Lee Weinstein, The Dalles Rep. Margaret Doherty, House District 35, Tigard Senator Jackie Dingfelder, Senate District 23, Portland special advisors Howard Lavine, Portland Charlie Walker, Neskowin Virginia Willard, Portland 2 oregon cultural trust December 2011 To the supporters and partners of the Oregon Cultural Trust: Culture continues to make a difference in Oregon – activating communities, simulating the economy and inspiring us. The Cultural Trust is an important statewide partner to Oregon’s cultural groups, artists and scholars, and cultural coalitions in every county of our vast state. We are pleased to share a summary of our Fiscal Year 2011 (July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011) activity – full of accomplishment. The Cultural Trust’s work is possible only with your support and we are pleased to report on your investments in Oregon culture. -

A Free Emigrant Road 1853: Elijah Elliott's Wagons

Meek’s Cutoff: 1845 Things were taking much longer than expected, and their Macy, Diamond and J. Clark were wounded by musket supplies were running low. balls and four horses were killed by arrows. The Viewers In 1845 Stephen Hall Meek was chosen as Pilot of the 1845 lost their notes, provisions and their geological specimens. By the time the Train reached the north shores of Harney emigration. Meek was a fur trapper who had traveled all As a result, they did not see Meek’s road from present-day Lake, some of the men decided they wanted to drive due over the West, in particular Oregon and California. But Vale into the basin, but rode directly north to find the west, and find a pass where they could cross the Cascade after a few weeks the independently-minded ‘45ers decided Oregon Trail along Burnt River. Mountains. Meek was no longer in control. When they no Pilot was necessary – they had, after all, ruts to follow - Presented by Luper Cemetery Inc. arrived at Silver River, Meek advised them to turn north, so it was not long before everyone was doing their own Daniel Owen and follow the creek to Crooked River, but they ignored his thing. Great-Grandson of Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Owen advice. So the Train headed west until they became bogged down at the “Lost Hollow,” on the north side of Wagontire Mountain. Here they became stranded, because no water could be found ahead, in spite of the many scouts searching. Meek was not familiar with this part of Oregon, although he knew it was a very dry region. -

Have Gun, Will Travel: the Myth of the Frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall

Feature Have gun, will travel: The myth of the frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall Newspaper editor (bit player): ‘This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, we print the legend’. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (dir. John Ford, 1962). Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott): ‘You know what’s on the back of a poor man when he dies? The clothes of pride. And they are not a bit warmer to him dead than they were when he was alive. Is that all you want, Steve?’ Steve Judd (Joel McCrea): ‘All I want is to enter my house justified’. Ride the High Country [a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon] (dir. Sam Peckinpah, 1962)> J. W. Grant (Ralph Bellamy): ‘You bastard!’ Henry ‘Rico’ Fardan (Lee Marvin): ‘Yes, sir. In my case an accident of birth. But you, you’re a self-made man.’ The Professionals (dir. Richard Brooks, 1966).1 he Western movies that from Taround 1910 until the 1960s made up at least a fifth of all the American film titles on general release signified Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, John Wayne and Strother Martin on the set of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance escapist entertainment for British directed and produced by John Ford. audiences: an alluring vision of vast © Sunset Boulevard/Corbis open spaces, of cowboys on horseback outlined against an imposing landscape. For Americans themselves, the Western a schoolboy in the 1950s, the Western believed that the western frontier was signified their own turbulent frontier has an undeniable appeal, allowing the closing or had already closed – as the history west of the Mississippi in the cinemagoer to interrogate, from youth U. -

Jeannette Baum AUGUST STANGE and STANGE

Jeannette Baum AUGUST STANGE AND STANGE MANOR JB: As I recall, Mr. And Mrs. Stange came to La Grande with their two daughters. They lived in a house now occupied by the Chinese restaurant on Fourth Street while they were building their lovely manor on the hill. That was about 1910. I: I believe the Mt. Emily Lumber Company was started by August Stange. JB: That is correct. He bought Bowman Hicks Lumber and renamed it Mt. Emily Lumber. I: Do you know why they came to La Grande specifically? JB: I suppose for lumber. I: Perhaps he learned of the sale of Bowman Hicks through a national advertisement? JB: That could be. The same thing happened with Mr. Hoffman. He was in Tennessee, and came west to take advantage of the timber. He bought a lumberyard in Union. These people came west to take advantage of a more lucrative situation. I: Did you ever hear of a brother who may have been here before August arrived? JB: I was never aware of a brother. I: When did you first meet or learn about the Stanges? JB: We came to La Grande after the war. You didn’t come into La Grande and not know about the Stanges because their house, itself, attracted attention. David, my husband, admired the house so extensively I think that, in the back of his mind, he thought he would own that house. The first time I saw the house inside is when we went to look at it in early 1962, when it went on the market. -

2012 Conference Program

WEDNESDAY 1 IMAGINATION IS THE 21ST CENTURY TECHNOLOGY AUGUST 8-11, 2012 WELCOME Welcome to Columbia College Chicago and the 2012 University Film and Video Association Conference. We are very excited to have Peter Sims, author of Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge From Small Discoveries, as our keynote speaker. Peter’s presentation on the morning of Wednesday August 8 will set the context for the overall conference focus on creativity and imagination in film and video education. The numerous panel discussions and presentations of work to follow will summarize the current state of our field and offer opportunities to explore future directions. This year we have a high level of participation from vendors servicing our field who will present the latest technologies, products, and services that are central to how we teach everything from theory and critical studies to hands-on screen production. Of course, Chicago is one of the world’s greatest modern cities, and the Columbia College campus is ideally placed in the South Loop for access to Lake Michigan and Grant Park with easy connections to the music and theater venues for which the city is so well known. We hope you have a stimulating and enjoyable time at the 2012 Conference. Bruce Sheridan Professor & Chair, Film & Video Department Columbia College Chicago 2 WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY 3 WE WOULD LIKE TO THANK OUR GENEROUS COFFEE BREAKS FOR THE CONFERENCE WILL BE SPONSORS FOR THEIR SUPPORT OF UFVA 2012. HELD ON THE 8TH FLOOR AMONG THE EXHIBIT PLEASE BE SURE TO VISIT THEIR BOOTHS. BOOTHS AND HAVE BEEN GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY ENTERTAINMENT PARTNERS. -

Sun Valley Film Festival Announces Its Awards For

Oct-14 Nov-14 Dec-14 Jan-15 Feb-15 Mar-15 Website Unique Visitors 2607 4029 4611 7549 5327 6313 Website Total Visits 3944 5566 6568 9160 7892 9292 Website Pages 11961 12480 14516 20891 18380 21002 Website Statistics Q2 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 Oct-14 Nov-14 Dec-14 Jan-15 Feb-15 Mar-15 Website Unique Visitors Website Total Visits Website Pages DATE: March 31, 2015 TO: HAILEY CHAMBER OF COMMERCE INVOICE: PR/COMMUNICATIONS SERVICES FOR 2015 SUN VALLEY FILM FESTIVAL November 2014 – March 2015 AMOUNT: $2500.00 Payable net 30 days DETAIL OF SERVICES: STRATEGIC PUBLIC RELATIONS EFFORTS: 1. Media Outreach Actively pursue targeted pitches to key local, regional and national consumer, travel, arts, ski media . Local & regional media/online sites – arrange for media interviews with SVFF staff as feasible . National & Regional consumer travel, arts, ski media (print, online, TV, radio, bloggers, etc) . Develop PR strategic plan and schedule with SVFF marketing director . Press release outreach/distribution to regional/national media outlets (Note: Film & Entertainment consumer/trade media outreach to be handled by BWR PR) SVFF Announcement Party – Boise – Feb 15 . Represent SVFF at the event, work with media on coverage prior, during, post-event 3. Media Assistance Assist with key targeted media invited to attend and cover the SVFF . Identify target list with SVFF/BWR, extend invites, secure ITC funds for media travel & lodging costs, secure in-kind lodging for media with SV Resort, coordinate other arrangements as needed Press Credentialing/Press Materials & Assistance . Set up online press credential application form, review applications, confirm credentials/details . -

Historical Grant Purchases - FY2014-15

17 SW Frazer Ave., Suite 360 PO Box 1689 Pendleton, OR 97801 Phone (541) 276-6449 Historical Grant Purchases - FY2014-15 Item Title Format ISBN Library/Libraries Accidental cowgirl Book Helix PL Accidental cowgirl rides again Book Helix PL All around and the 13th juror / Rick Steber Book 9780945134428 Adams PL American dreamers : how two Oregon farm kids transformed an industry, a community, and a university / Austin Book Echo PL Astoria : John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson’s lost Pacific Empire : a story of wealth, ambition, and survival / Peter Stark Book Echo PL Badger and Coyote were neighbors : Melville Jacobs on Northwest Indian myths and tales / William R. Seaburg Book Umatilla PL Basalt City / Lawrence Hobart Book 1480276081 Hermiston PL Betty Feves : generations / Betty Feves, Namita Gupta Wiggers, Damara Bartlett, et. al. Book Pendleton PL Bigfoot casebook updated : sightings and encounters from 1818 to 2004 / Janet Bord Book Umatilla PL Bound for Oregon / Jean VanLeeuwen Book Helix PL Building the Columbia River Highway : they said it couldn’t be done / Peg Willis Book 9781626192713 Adams PL Burning fences : a western memoir of fatherhood / Craig Lesley Book Stanfield PL Caught in the crosshairs : a true eastern Oregon mystery / Rick Steber Book 9780945134398 Helix PL, Stanfield PL Conrad and the cowgirl next door / Denette Fretz Book 9780310723493 Adams PL Discovering Main Street : travel adventures in small towns in the Northwest / Foster Church Book Umatilla PL Dreams of the West : a history of the Chinese in Oregon 1850-1950 Book 9781932010138 Athena PL, Hermiston PL Finding her way / Leah Banicki Book Ukiah Lib. -

Indigenous Sacred Ways 33

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYS 33 CHAPTER 2 INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYS “Everything is alive” Listen to the Chapter Audio on myreligionlab KEY TOPICS Here and there around the globe, pockets of people still follow local sacred • Understanding ways handed down from their remote ancestors and adapted to contemporary indigenous circumstances. These are the traditional indigenous peoples—descendants sacred ways 34 of the original inhabitants of lands now controlled by larger political systems • Cultural in which they may have little infl uence. Their distribution around the world, diversity 36 suggested in the map overleaf, reveals a fascinating picture with many indigenous • The circle groups surviving in the midst of industrialized societies, but with globalization of right processes altering what is left of their traditional lifeways. relationships 39 Indigenous peoples comprise at least four percent of the world’s population. • Spiritual Some who follow the ancient spiritual traditions still live close to the earth specialists 48 in nonindustrial, small-scale cultures; many do not. But despite the disruption • Group of their traditional lifestyles, many indigenous peoples maintain a sacred way observances 55 of life that is distinctively different from all other religions. These enduring • Globalization 60 ways, which indigenous peoples may refer to as their “original instructions” on how to live, were almost lost under the onslaught of genocidal colonization, • Development conversion pressures from global religions, mechanistic materialism, and the issues 64 destruction of their natural environments by the global economy of limitless consumption. To what extent can [indigenous groups] reinstitute traditional religious values in a world gone mad with development, electronics, almost instantaneous transportation facilities, and intellectually grounded in a rejection of spiritual and mysterious events? Vine Deloria, Jr.1 Much of the ancient visionary wisdom has disappeared. -

Traditional Resource Use of the Flagstaff Area Monuments

TRADITIONAL RESOURCE USE OF THE FLAGSTAFF AREA MONUMENTS FINAL REPORT Prepared by Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 86721 July 19, 2004 TRADITIONAL RESOURCE USE OF THE FLAGSTAFF AREA MONUMENTS FINAL REPORT Prepared by Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle Shawn Kelly Jill Dumbauld with contributions by Nathan O’Meara Kathleen Van Vlack Fletcher Chmara-Huff Christopher Basaldu Prepared for The National Park Service Cooperative Agreement Number 1443CA1250-96-006 R.W. Stoffle and R.S. Toupal, Principal Investigators Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 86721 July 19, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................iv CHAPTER ONE: STUDY OVERVIEW ..................................................................................1 Project History and Purpose...........................................................................................1 Research Tasks...............................................................................................................1 Research Methods..........................................................................................................2 Organization of the Report.............................................................................................7 -

The Biology of Religious Behavior

The Biology of Religious Behavior The Biology of Religious Behavior The Evolutionary Origins of Faith and Religion Edited by Jay R. Feierman PRAEGER An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC Copyright © 2009 by Jay R. Feierman All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The biology of religious behavior : the evolutionary origins of faith and religion / edited by Jay R. Feierman. p. cm. Proceedings of a symposium held in July 2008 at the University of Bologna, Italy. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–313–36430–3 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–313–36431–0 (ebook) 1. Psychology, Religious—Congresses. 2. Human evolution—Religious aspects—Congresses. I. Feierman, Jay R. BL53.B4655 2009 200.1’9—dc22 2009010608 131211109 12345 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To all whose lives have been affected by religion. Contents Preface xi Introduction xv PART ONE: DESCRIPTION OF RELIGIOUS BEHAVIOR 1 Chapter 1: The Evolution of Religious Behavior in Its 3 Socioecological Contexts Stephen K. Sanderson Chapter 2: Toward a Testable Definition of Religious Behavior 20 Lyle B. -

Scms 2017 Conference Program

SCMS 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM FAIRMONT CHICAGO MILLENNIUM PARK March 22–26, 2017 Letter from the President Dear Friends and Colleagues, On behalf of the Board of Directors, the Host and Program Committees, and the Home Office staff, let me welcome everyone to SCMS 2017 in Chicago! Because of its Midwestern location and huge hub airport, not to say its wealth of great restaurants, nightlife, museums, shopping, and architecture, Chicago is always an exciting setting for an SCMS conference. This year at the Fairmont Chicago hotel we are in the heart of the city, close to the Loop, the river, and the Magnificent Mile. You can see the nearby Millennium Park from our hotel and the Art Institute on Michigan Avenue is but a short walk away. Included with the inexpensive hotel rate, moreover, are several amenities that I hope you will enjoy. I know from previewing the program that, as always, it boasts an impressive display of the best, most stimulating work presently being done in our field, which is at once singular in its focus on visual and digital media and yet quite diverse in its scope, intellectual interests and goals, and methodologies. This year we introduced our new policy limiting members to a single role, and I am happy to say that we achieved our goal of having fewer panels overall with no apparent loss of quality in the program or member participation. With this conference we have made presentation abstracts available online on a voluntary basis, and I urge you to let them help you navigate your way through the program. -

Biennial Report 2014-2016

THIRTY-SECOND BIENNIAL REPORT JULY 1, 2014 THROUGH JUNE 30, 2016 NEW MEXICO LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL SERVICE NEW MEXICO LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL SERVICE New Mexico Legislative Council Service 411 State Capitol Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 (505) 986-4600 www.nmlegis.gov 202.204516 TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW The 2014-2016 Biennium in Brief Interims......................................................................................................................... 3 Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 5 THE NEW MEXICO LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Membership ............................................................................................................................. 11 Historical Background ............................................................................................................. 13 Duties .................................................................................................................................... 13 Policy Change.......................................................................................................................... 15 Interim Committees Permanent Legislative Education Study Committee .................................................................... 19 Legislative Finance Committee .................................................................................. 20 Statutory and New Mexico Legislative Council-Created Courts, Corrections and Justice Committee ..............................................................