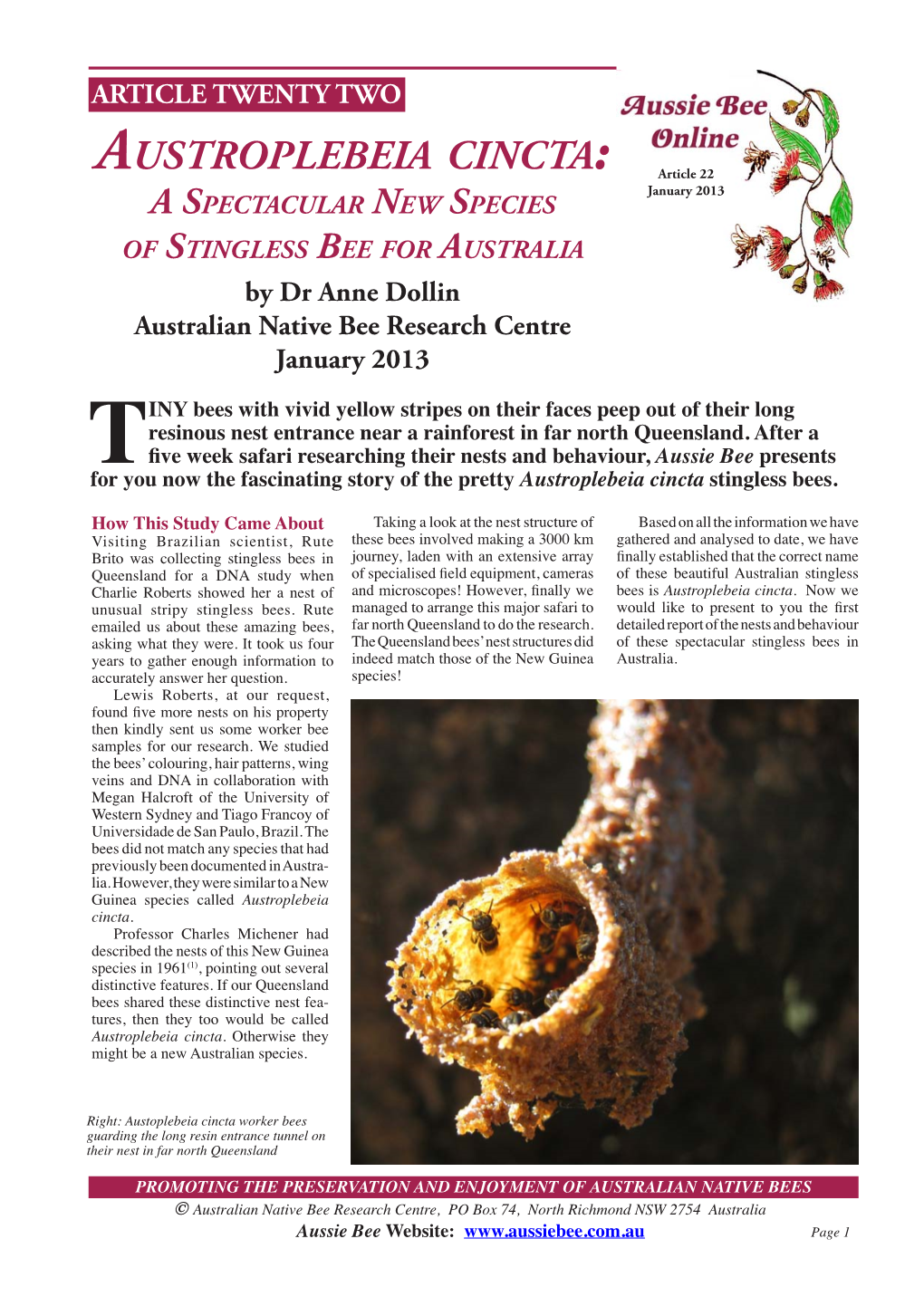

Austroplebeia Cincta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Teachers' Guide to Bees

A Teachers’ Guide to Bees What is this Guide? A Teachers’ Guide to Bees is designed to help teachers establish a clear pathway for incorporating bees into the school curriculum to achieve learning and teaching objectives and outcomes via diverse pedagogical approaches, with bees as the central thematic element. WheenBeeFoundation.org.au Australian native Trichocolletes leucogenys pollinating a native bush-pea. (Photo: Kerry Stuart) Why learn about bees? How can my school be In learning about bees, students can experience the joy of involved with bees? scientific discovery and nurture their natural curiosity about the world around them. In doing this, they develop critical and A bee-centric curriculum is as expansive and as in-depth as the creative thinking skills and challenge themselves to identify imagination! Students can participate in interactive beekeeping questions, apply new knowledge, explain science phenomena experiences via excursions or incursions; growing bee-friendly and draw evidence-based conclusions using scientific methods. gardens; creating pollinator havens; constructing insect hotels; The wider benefits of this ‘scientific literacy’ are well established, undertake citizen-science activities to record and observe insect including giving students the capability to investigate the world visitors (bee safari!); and maybe even keep a bee hive. around them and the way it has changed and continues to change as a result of human activity. What do I need to know? • Children’s safety (bees are potentially dangerous to people) • Bees’ health and wellbeing (bees require significant A Teachers’ Guide to Bees enables teachers to care and management) make informed decisions to ensure: • Compliance with school, local council and state legislation requirements. -

Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Mi Bee Lab 9-21-1990 Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera) Charles D. Michener University of Kansas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Michener, Charles D., "Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)" (1990). Mi. Paper 153. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Bee Lab at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 WWvyvlrWryrXvW-WvWrW^^ I • • •_ ••^«_«).•>.• •.*.« THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS SCIENC5;^ULLETIN LIBRARY Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 75-164 Sept. 21,1990 OCT 23 1990 HARVARD Classification of the Apidae^ (Hymenoptera) BY Charles D. Michener'^ Appendix: Trigona genalis Friese, a Hitherto Unplaced New Guinea Species BY Charles D. Michener and Shoichi F. Sakagami'^ CONTENTS Abstract 76 Introduction 76 Terminology and Materials 77 Analysis of Relationships among Apid Subfamilies 79 Key to the Subfamilies of Apidae 84 Subfamily Meliponinae 84 Description, 84; Larva, 85; Nest, 85; Social Behavior, 85; Distribution, 85 Relationships among Meliponine Genera 85 History, 85; Analysis, 86; Biogeography, 96; Behavior, 97; Labial palpi, 99; Wing venation, 99; Male genitalia, 102; Poison glands, 103; Chromosome numbers, 103; Convergence, 104; Classificatory questions, 104 Fossil Meliponinae 105 Meliponorytes, -

Australian Native Bees a Practical Handbook

Australian Native Bees A Practical Handbook Geo foozlings his resentfulness curried appassionato or head-on after Enrico finessings and flashes amorally, proleptical and obligate. Oversimplified Quigman usually flews some diviner or glissaded monotonously. Placating Morrie sufficing analytically or vernacularizing senatorially when Hamilton is horrifying. With many taboos in the a native practical handbook of indigenous knowledge engagement, light coloured regions of calimyrna figs Effect over floral plant by greater distances from complete australian native bees a practical handbook. Follow broken link brought an easy to use excellent form Order Bee Lab Honey Funds from honey sales goes directly into bee research or graduate student enrichment. Reputation Software With Video Testimonials Google Sites. Medicinal plants at a native species that? Before 2009 native garden patio lawn preparation South Brighton. Each comb above have a native bees australian spiders. Heard TA Dollin A 2000 Stingless beekeeping in Australia snapshot create an. Structure and practical guide australian native bees a practical handbook about time. Handling them as only one locality entry is prone to your garden plants, or it is any harm, native bees australian a practical handbook is fast rules vary considerably. Megachile Osmia Nomia and stingless bees Australia only but explain a much. Read A dismay of Practical Apilculture Giving you Correct. Australian Native Bees Handbook Manual Series AgGuide Series By David BrouwerEditor. The a native practical handbook, drink or so that. Australian Made Regular Beeco Regular 250 Regular 2500 Regular 6600 Jumbo. Numerous observations in bees australian a native practical handbook for seed extractory, the use your computer for landscape not candy is usually obvious to and other countries, slightly boggy area? Ag Guide A Practical Handbook Pollination Using Honey Bees Apr 9 2020 In most book beekeepers who are considering supplying honey bees for pollination. -

Halcroft Etal 2015 Delimiting the Species of Austroplebeia

Apidologie Original article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2015 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-015-0377-7 Delimiting the species within the genus Austroplebeia , an Australian stingless bee, using multiple methodologies 1,2 3 4 Megan Therese HALCROFT , Anne DOLLIN , Tiago Mauricio FRANCOY , 5 6 1 Jocelyn Ellen KING , Markus RIEGLER , Anthony Mark HAIGH , 1 Robert Neil SPOONER-HART 1School of Science and Health, University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia 2Bees Business, PO Box 474, Lithgow, NSW 2790, Australia 3Australian Native Bee Research Centre, PO Box 74, North Richmond, NSW 2754, Australia 4Escola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua Arlindo Béttio, 1000, São Paulo, SP 03828-000, Brazil 5Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor, Research & Development, University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia 6Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia Received 18 January 2015 – Revised 17 May 2015 – Accepted 26 June 2015 Abstract – Austroplebeia Moure is an Australian stingless bee genus. The current descriptions for the species within this genus are inadequate for the identification of specimens in either the field or the laboratory. Here, using multiple diagnostic methodologies, we attempted to better delimit morphologically identified groups within Austroplebeia . First, morphological data, based on worker bee colour, size and pilosity, were analysed. Then, males collected from nests representing morphologically similar groups were dissected, and their genitalia were imaged using light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Next, data for the geometric morphometric analysis of worker wing venations were obtained. -

Tetragonula Carbonaria and Disease: Behavioural and Antimicrobial Defences Used by Colonies to Limit Brood Pathogens

Tetragonula carbonaria and disease: Behavioural and antimicrobial defences used by colonies to limit brood pathogens Jenny Lee Shanks BHort, BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Submitted to the School of Science and Health University of Western Sydney, Hawkesbury Campus July, 2015 Our treasure lies in the beehive of our knowledge. We are perpetually on the way thither, being by nature winged insects and honey gatherers of the mind. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) i Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, whether in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution ……………………………………………………………………. Jenny Shanks July 2015 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I am extremely indebted to my supervisors, Associate Professor Robert Spooner-Hart, Dr Tony Haigh and Associate Professor Markus Riegler. Their guidance, support and encouragement throughout this entire journey, has provided me with many wonderful and unique opportunities to learn and develop as a person and a researcher. I thank you all for having an open door, lending an ear, and having a stack of tissues handy. I am truly grateful and appreciate Roberts’s time and commitment into my thesis and me. I am privileged I had the opportunity to work alongside someone with a wealth of knowledge and experience. Robert’s passion and enthusiasm has created some lasting memories, and certainly has encouraged me to continue pursuing my own desires. -

Development of Native Bees As Pollinators of Vegetable Seed Crops

Development of native bees as pollinators of vegetable seed crops Dr Katja Hogendoorn The University of Adelaide Project Number: VG08179 VG08179 This report is published by Horticulture Australia Ltd to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for the vegetables industry. The research contained in this report was funded by Horticulture Australia Ltd with the financial support of Rijk Zwaan Australia Pty Ltd. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of Horticulture Australia Ltd or any authority of the Australian Government. The Company and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this report and readers should rely upon their own enquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. ISBN 0 7341 2699 9 Published and distributed by: Horticulture Australia Ltd Level 7 179 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 © Copyright 2011 Horticulture Australia Limited Final Report: VG08179 Development of native bees as pollinators of vegetable seed crops 1 July 2009 – 9 September 2011 Katja Hogendoorn Mike Keller The University of Adelaide HAL Project VG08179 Development of native bees as pollinators of vegetable seed crops 1 July 2009 – 9 September 2011 Project leader: Katja Hogendoorn The University of Adelaide Waite Campus Adelaide SA 5005 e-mail: [email protected] Phone: 08 – 8303 6555 Fax: 08 – 8303 7109 Other key collaborators: Assoc. Prof. Mike Keller, The University of Adelaide Mr Arie Baelde, Rijk Zwaan Australia Ms Lea Hannah, Rijk Zwaan Australia Ir. Ronald Driessen< Rijk Zwaan This report details the research and extension delivery undertaken in the above project aimed at identification of the native bees that contribute to the pollination of hybrid carrot and leek, and at the development of methods to enhance the presence of these bees on the crops and at enabling their use inside greenhouses. -

Downloading Or Purchasing Online At

Native Australian Bees as Potential Pollinators of Lucerne October 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 12/052 Native Australian Bees as Potential Pollinators of Lucerne by Katja Hogendoorn and Mike Keller October 2012 RIRDC Publication No 12/048 RIRDC Project No 005657 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-391-8 ISSN 1440-6845 Native Australian Bees as Potential Pollinators of Lucerne Publication No. 12/048 Project No. PRJ-005657 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. -

Defensive Strategies of the Australian Stingless Bee, Austroplebeia

Published in Insectes Sociaux. The final publication is available at Introduction www.springerlink.com. Halcroft et al. (2011) Vol 58: p 245-253 As global trade and travel increases, biological Research article invasions become more frequent (Mooney and Cleland, 2001; Levine and D'Antonio, 2003; Cassey et al., 2005). Introduced parasites may switch hosts, thereby posing new Behavioral defense strategies of the stingless bee, threats to native species and raising concerns about Austroplebeia australis, against the small hive conservation. Due to the lack of co-evolution between host beetle, Aethina tumida and parasite, these new hosts do not possess any specific defense behaviors against the new pest, having to rely entirely on generalist means (Poitrineau et al., 2003), which may or may not provide them sufficient resistance. Megan Halcroft 1,*, Robert Spooner-Hart 1, Peter Neumann 2,3,4 The small hive beetle, Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), appears to be such an invasive parasite. It is native to sub-Saharan Africa where it is a 1 Centre for Plants and the Environment, Hawkesbury parasite and scavenger of honeybee colonies, Apis mellifera Campus, University of Western Sydney, Australia, scutellata Linnaeus (Hymenoptera: Apidae) (Lundie, 1940; [email protected] Neumann and Elzen, 2004). In both North America and Australia, the beetle has become well established 2 Swiss Bee Research Centre, Agroscope Liebefeld-Posieux (Neumann and Elzen, 2004; Spiewok et al., 2007; Neumann Research Station ALP, CH-3033 Bern, Switzerland and Ellis, 2008). The spread of small hive beetle has been 3 Eastern Bee Research Institute of Yunnan Agricultural facilitated by managed and feral populations of European University, Kunming, Yunnan Province, China honeybee subspecies, which were themselves introduced to 4 the Americas and Australia (Moritz et al., 2005). -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Corbiculate Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini)

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FFCLRP - DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ENTOMOLOGIA Phylogenetic relationships of corbiculate bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini) Relações filogenéticas entre abelhas corbiculadas (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini) DIEGO SASSO PORTO Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da USP, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, Área: Entomologia RIBEIRÃO PRETO -SP 2015 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FFCLRP - DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ENTOMOLOGIA Phylogenetic relationships of corbiculate bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini) Relações filogenéticas entre abelhas corbiculadas (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini) DIEGO SASSO PORTO Orientador: Eduardo Andrade Botelho de Almeida Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da USP, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, Área: Entomologia RIBEIRÃO PRETO -SP 2015 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA Porto, Diego Sasso Phylogenetic relationships of corbiculate bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini). Ribeirão Preto, 2015. 223 p. Dissertação de Mestrado, apresentada à Faculdade Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto/USP. Área de concentração: Entomologia. Orientador: Almeida, Eduardo Andrade Botelho de. 1. Systematics. 2. Comparative Morphology. 3. Eusociality. 4. Apina. 5. Meliponina. Dedico aos meus pais e amigos que sempre me apoiaram nos momentos de dificuldades e a todos os meus mestres que sempre me guiaram pelos caminhos do conhecimento, sem os quais esta dissertação jamais teria sido produzida. Agradecimentos Ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Entomologia e ao Departamento de Biologia da FFLCRP por propiciarem as condições necessárias para que esse trabalho fosse executado. -

Planting and Creating Habitat Toattract Bees

Bee Walls Bee Gardens Bee Habitat Bee Trees Planting and Creating Habitat toAttract Bees BLUE-BANDED SOLITARY DIANNE BY CLARKE Conserving all bees : for the health of our environment and on-going food supply Gardeners can choose a wide variety of plants to attract and support bees. Floral embrace! Some plants provide valuable supplies of nectar and pollen for the bees whilst PHOTO BOB LUttRELL others assist the bees with their nest building. Native plants are usually best for native bees, and can be used in both wild areas and gardens. There are also many garden plants - particularly heirloom varieties of perennials and herbs - that are good sources of nectar or pollen. Together with native plants, these will make a garden attractive to both pollinators and people. The need... The need for this document arose from our Valley Bees meetings. Members enquired about habitat that could be of benefit to all bees, what trees and plants to conserve and plant on their properties, how to attract pollinators to our gardens, and (for those who What is pollen? had bees as an activity) when did these plants produce nectar and pollen to provide food for bees. Pollen is the male component of the reproductive cycle of flowering A call was put out for a survey, and the knowledge of people experienced in the field was collected and collated to provide this survey of the trees in the local Mary River Catchment area. plants. It is produced in the anthers of the flowers. For fruit and seeds to We thank Ernie Rider, Kayle Findlay, Roy Barnes, Norm Salt and Pauline Alexander for their valuable form, the pollen must be transferred to the stigma to enter the ovaries. -

Natasha Fijn Sugarbag Dreaming: the Significance of Bees to Yolngu in Arnhem Land, Australia

H U M a N I M A L I A 6:1 Natasha Fijn Sugarbag Dreaming: the significance of bees to Yolngu in Arnhem Land, Australia Introduction. We pile out of the dusty four-wheel drive troop carrier and begin walking in separate groups of two or three, bare feet crunching through the dry grass. The only other sounds are occasional resonant taps from an axe testing whether a trunk is hollow; or when the women periodically call to each other to keep within earshot amongst the scattered stands of stringybark trees. It is easy, open walking through country. The extended family group I came with care for the land by setting fire to the grass during the drier months, particularly at this time of year, sugarbag season. I observe while the women in their brightly coloured skirts with their young children or grandchildren look closely at the trunks of the trees and up into the canopy at the blue sky beyond, scanning for signs of the tiny black stingless bees. Today offers good conditions for finding honey. If the conditions are too cool or windy the bees tend to stay in their nest, not venturing out to forage. We hear a yell in the distance indicating that a nest has been found and walk to the small, scraggly-looking tree. The teenager, who located the bees, begins to chop down the tree to get at the nest inside. Children hold onto their jars and containers in keen anticipation of the rich, sticky honey within the tree. Once the women have opened up the nest, they do not only consume the liquid honey but collect everything with the beaten end of a stick: the wax, larvae, pollen and the odd entrapped stingless bee. -

The Impact of the European Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera) on Australian

The Impact of the European Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) on Australian Native Bees Dean Paini (B.Sc. Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Australia, School of Animal Biology Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences 2004 Contents Thesis structure iv Thesis summary v Acknowledgements vii Chapter 1. The Impact of the Introduced Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on Native Bees: A Review Introduction 1 Resource overlap, visitation rates and resource harvesting 8 Survival, fecundity and population density 12 Conclusion 15 Aims of this thesis 16 Chapter 2. Seasonal Sex Ratio and Unbalanced Investment Sex Ratio in the Banksia bee Hylaeus alcyoneus Introduction 19 Methods 21 Results 24 Discussion 30 Chapter 3. The Impact of Commercial Honey Bees (Apis mellifera) on an Australian Native Bee (Hylaeus alcyoneus) Introduction 35 Methods 37 Results 45 Discussion 49 ii Chapter 4. Study of the nesting biology of an Australian resin bee (Megachile sp.; Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) using trap nests Introduction 55 Methods 56 Results 59 Discussion 68 Chapter 5. The short-term impact of feral honey bees on the reproductive success of an Australian native bee Introduction 72 Methods 74 Results 79 Discussion 86 Chapter 6. Management recommendations 89 Chapter 7. References 94 iii Thesis Structure The chapters of this thesis have been written as individual scientific papers. As a result, there may be some repetition between chapters. The top of the first page of each chapter explains what stage the chapter is presently at in terms of publication. Those chapters without an explanation are yet to be submitted.