The Temple Mount Is in Our Hands!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B'tselem" Representatives; We Will Therefore Address This Claim in Short

מרכז המידע הישראלי לזכויות האדם בשטחים (ע.ר.) B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories -DRAFT- Take No Prisoners The Fatal Shooting of Palestinians by Israeli Security Forces during “Arrest Operations” May 2005 Researched and written by Ronen Shnayderman Data coordination by Suhair ‘Abdi, Antigona Ashkar, Shlomi Swissa, Sohad Sakalla Fieldwork by `Atef Abu a-Rob, Salma Deba’i, Musa Abu Hashhash Translated by Shaul Vardi Edited by Zvi Shulman רחוב התעשייה 8, ת.ד. 53132, ירושלים 91531, טלפון 6735599 (02), פקס 6749111 (02) 8 Hata’asiya St. (4th Floor), P.O.Box 53132, Jerusalem 91531, Tel. (02) 6735599, Fax (02) 6749111 [email protected] http://www.btselem.org Introduction In the early morning of Friday, 3 December 2004, IDF soldiers killed Mahmud `Abd a-Rahman Hamdan Kmeil in Raba, a village southeast of Jenin. The press release by the IDF Spokesperson stated that during an operation to arrest Kmeil, he was shot and killed while attempting to escape from the house in which he was hiding. However, testimonies collected by B’Tselem from eyewitnesses raise grave concerns that the IDF soldiers executed Kmeil as he lay injured on the ground, after his weapon had been taken from him. During the course of the second intifada, Israel officially adopted a policy of assassinating Palestinians suspected of belonging to the armed Palestinian organizations.1 Israel argues that the members of these organizations are combatants and are, therefore, a legitimate target of attack. However, Israel does not grant them the rights given to combatants by international humanitarian law, primarily the right to be recognized as a prisoner of war when captured, which entails immunity from criminal prosecution. -

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

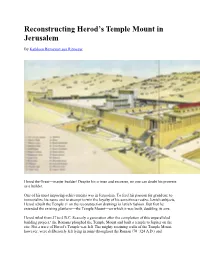

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

UNDER COVER of DARKNESS Night Arrests of Palestinian Minors by Israeli Security Forces in the West Bank

UNDER COVER OF DARKNESS Night Arrests of Palestinian Minors by Israeli Security Forces in the West Bank UNDER COVER OF DARKNESS 1 UNDER COVER OF DARKNESS Night Arrests of Palestinian Minors by Israeli Security Forces in the West Bank October 2020 UNDER COVER OF DARKNESS Night Arrests of Palestinian Minors by Israeli Security Forces in the West Bank Research and writing: Shelly Cohen Editing, writing and research assistance: Andrea Szlecsan Data coordination: Orly Bermack, Morad Muna, Yarin Szachter Affidavits taken by Adv. Tagrid Shabita Legal advice: Adv. Nadia Daqqa, Adv. Daniel Shenhar Translation: MJ Translations Copy editing: Shelly Cohen Cover illustration: Noa Finkelstein Graphic design: Sofi Cooperative Typesetting and layout: Debora Pollak October 2020 HaMoked wishes to thank the hundreds of individuals and institutions in Israel and around the world that support its activities. Over half of our funding is provided by foreign government entities. A full list of donors appears on the website of the Israeli Registrar of Non-Profit Organizations and HaMoked's website. ISBN 978-965-7625-05-7 Contents 6 Introduction 8 Night arrests: A routine affair 10 Systemic violation of minorsˈ rights in night arrests 23 Summoning minors for interrogation: The appropriate alternative to pre-planned night arrests 26 Conclusions and recommendations Introduction Hundreds of times a year, Israeli troops invade Palestinian 1 Figures provided to HaMoked homes in the West Bank in the middle of the night, sow fear in response to a Freedom of and panic among household members – children and adults Information application alike – and take a teenager from the family into custody.1 indicate that Israeli security forces arrested 970 The arrests are a violent affair: the soldiers often break Palestinian minors from the down the front door and sometimes forcefully drag the West Bank in 2018 and 855 in teenagers out of bed. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (May 9-15, 2018)

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ה ש ל מ ( למ מ" ) רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ה ש ל מ ( למ מ" ) News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (May 9-15, 2018) Overview Events this past week focused on the violent, pre-planned demonstrations of the "great return march" on May 14, 2018. They were accompanied by mass riots along the Gaza Strip border. They were held on the same day the ceremony was held marking the relocation of the United States embassy to Jerusalem. In the Gaza Strip about 40,000 people demonstrated and rioted at 13 locations along the security fence. During the riots 60 Palestinians were killed (their organizational identities are currently being examined by the ITIC). IDF sources stressed the violence on the Palestinian side, noting it was higher than the violence of the past weeks. Under cover of the riots, terrorist operatives carried out and attempted to carry out attacks, placing IEDs and shooting at IDF forces. Hamas and the other terrorist organizations called on the residents of Judea and Samaria to join the demonstrations. Response was poor. Prominent was a large demonstration near the Qalandia crossing, attended by about 1,800 people, some of whom clashed with Israeli security forces. In the political sphere, the Palestinian Authority (PA) announced a number of measures, including joining international organizations (which the United States threatens to leave if the Palestinians are granted membership); submitting legal suits against Israel in the International Criminal Court in the The Hague (ICC) for its conduct (a "senior Palestinian source" claimed a case was being prepared against several IDF commanders, accusing them of "war crimes" against Palestinians in the Gaza Strip); and calling for emergency meetings of the UN Security Council and the UN Human Rights Council to appoint a committee to investigate Israel's actions. -

Boundaries, Barriers, Walls

1 Boundaries, Barriers, Walls Jerusalem’s unique landscape generates a vibrant interplay between natural and built features where continuity and segmentation align with the complexity and volubility that have characterized most of the city’s history. The softness of its hilly contours and the harmony of the gentle colors stand in contrast with its boundar- ies, which serve to define, separate, and segregate buildings, quarters, people, and nations. The Ottoman city walls (seefigure )2 separate the old from the new; the Barrier Wall (see figure 3), Israelis from Palestinians.1 The former serves as a visual reminder of the past, the latter as a concrete expression of the current political conflict. This chapter seeks to examine and better understand the physical realities of the present: how they reflect the past, and how the ancient material remains stimulate memory, conscious knowledge, and unconscious perception. The his- tory of Jerusalem, as it unfolds in its physical forms and multiple temporalities, brings to the surface periods of flourish and decline, of creation and destruction. TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOGRAPHY The topographical features of Jerusalem’s Old City have remained relatively con- stant since antiquity (see figure ).4 Other than the Central Valley (from the time of the first-century historian Josephus also known as the Tyropoeon Valley), which has been largely leveled and developed, most of the city’s elevations, protrusions, and declivities have maintained their approximate proportions from the time the city was first settled. In contrast, the urban fabric and its boundaries have shifted constantly, adjusting to ever-changing demographic, socioeconomic, and political conditions.2 15 Figure 2. -

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.)

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.) Leen Ritmeyer • 08/03/2018 This post was originally published on Leen Ritmeyer’s website Ritmeyer Archaeological Design. It has been republished with permission. Visit the website to learn more about the history of the Temple Mount and follow Ritmeyer Archaeological Design on Facebook. Following on from our previous drawing, the Temple Mount during the Hellenistic and Hasmonean periods, we now examine the Temple Mount during the Herodian period. This was, of course, the Temple that is mentioned in the New Testament. Herod extended the Hasmonean Temple Mount in three directions: north, west and south. At the northwest corner he built the Antonia Fortress and in the south, the magnificent Royal Stoa. In 19 B.C. the master-builder, King Herod the Great, began the most ambitious building project of his life—the rebuilding of the Temple and the Temple Mount in lavish style. To facilitate this, he undertook a further expansion of the Hasmonean Temple Mount by extending it on three sides, to the north, west and south. Today’s Temple Mount boundaries still reflect this enlargement. The cutaway drawing below allows us to recap on the development of the Temple Mount so far: King Solomon built the First Temple on the top of Mount Moriah which is visible in the center of this drawing. This mountain top can be seen today, inside the Islamic Dome of the Rock. King Hezekiah built a square Temple Mount (yellow walls) around the site of the Temple, which he also renewed. -

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museu

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museum Tower of David Herod’s Palace Temple Mount The Temple Mount, in Hebrew: Har HaBáyit, "Mount of the House of God", known to Muslims as the Haram esh-Sharif, "the Noble Sanctuary and the Al Aqsa Compound, is a hill located in the Old City of Jerusalem that for thousands of years has been venerated as a holy site in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike. The present site is a flat plaza surrounded by retaining walls (including the Western Wall) which was built during the reign of Herod the Great for an expansion of the temple. The plaza is dominated by three monumental structures from the early Umayyad period: the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock and the Dome of the Chain, as well as four minarets. Herodian walls and gates, with additions from the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods, cut through the flanks of the Mount. Currently it can be reached through eleven gates, ten reserved for Muslims and one for non-Muslims, with guard posts of Israeli police in the vicinity of each. According to Jewish tradition and scripture, the First Temple was built by King Solomon the son of King David in 957 BCE and destroyed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE – however no substantial archaeological evidence has verified this. The Second Temple was constructed under the auspices of Zerubbabel in 516 BCE and destroyed by the Roman Empire in 70 CE. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

ISRAEL Israel Is a Multiparty Parliamentary Democracy with A

ISRAEL Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy with a population of approximately 7.7 million, including Israelis living in the occupied territories. Israel has no constitution, although a series of "Basic Laws" enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a "State of Emergency," which has been in effect since 1948. The 120-member, unicameral Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The February 2009 elections for the Knesset were considered free and fair. They resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Israeli security forces reported to civilian authorities. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.) Principal human rights problems were institutional, legal, and societal discrimination against Arab citizens, Palestinian residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (see annex), non-Orthodox Jews, and other religious groups; societal discrimination against persons with disabilities; and societal discrimination and domestic violence against women, particularly in Bedouin society. While trafficking in persons for the purpose of prostitution decreased in recent years, trafficking for the purpose of labor remained a serious problem, as did abuse of foreign workers and societal discrimination and incitement against asylum seekers. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life The government or its agents did not commit politically motivated killings. The petitioners withdrew their appeal to the High Court against the closure of the inquiry by the Department for Investigations against Police Officers' (DIPO) into the 2008 beating and subsequent coma and death of Sabri al-Jarjawi, a Bedouin.