WACA HSR.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accessory Structure Permit

City of Port St. Lucie Building Department ACCESSORY STRUCTURE 121 S.W. Port St. Lucie Blvd Port St. Lucie, Fl. 34953 PERMIT APPLICATION Ph: 772 - 871 - 5132 Website: www.cityofpsl.com/building Shed Detached garage Tiki hut Pergola Gazebo Permit #: _____________________ Pin: _____________ Detached carport Detached workshop Other accessory structure CONSTRUCTION UNDER THIS PERMIT SHALL BE DONE IN ACCORDANCE WITH FBC 2020 7TH EDITION Site Address: Legal Description (Section/Block/Lot): Parcel ID: Owner’s Information Name: Email: Phone: Address: Contractor’s Information Name: Email: Phone: Address: PSL Comp no. State License no. PROJECT INFORMATION Commercial Residential Size of accessory structure: ________ x ________ Type of accessory structure: Prefab Constructed on site Manufacturer: _____________________________ Type of pad: Concrete Wood Size of slab: ________ x ________ Footing size: ________ x ________ Anchoring kit: Yes No Existing accessory structures: Are there any other accessory structures on this property? Yes No If yes, how many? _____ Footing size: ________ x ________ Size: ________ x ________ Total Valuation $_________________ APPLICATION MUST BE SIGNED AND NOTARIZED BY THE CONTRACTOR AND OWNER ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Contractor Signature Date Owner or Owner’s Authorized Representative Signature Date ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Miami-Dade County Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources Permit Exemptions

Miami-Dade County Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources Permit Exemptions Please note that the exemptions listed in this section for unincorporated Miami-Dade County are from Florida Building Code permit requirements only, unless otherwise noted. Other State and County regulatory departments and agencies may require approvals or permits. I. Buildings and Structures II. Items Not Regulated by the Florida Building Code III. Single-Family Residences, Duplexes, Townhouses, and Condominiums IV. Minor Repairs - Residential and Commercial Properties V. Satellite Antennas I. Buildings and Structures A. Under Section 553.73(10) of the Florida Statutes, the following buildings and structures are exempt from compliance with the Florida Building Code: a) Buildings and structures specifically regulated and preempted by the federal government. b) Railroads and ancillary facilities associated with the railroad. c) Non-residential farm buildings on farms (Requires Zoning Improvement Permit). d) Temporary buildings or sheds used exclusively for construction purposes (Requires Zoning Improvement Permit). e) Mobile or modular structures used as temporary offices, except that the provisions of Part II relating to accessibility by persons with disabilities shall apply to such mobile or modular structures. f) Electric utilities' structures or facilities, as defined in Section 366.02, Florida Statutes, which are directly involved in the generation, transmission or distribution of electricity. g) Temporary sets, assemblies, or structures used in commercial motion picture or television production, or any sound-recording equipment used in such production, on or off the premises. h) Chickees constructed by the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians or the Seminole Tribe of Florida. The term "chickee" means an open-sided wooden hut that has a thatched roof or palmetto or other traditional materials, and that does not incorporate any electrical, plumbing, or other non- wood features (Requires Zoning Improvement Permit). -

Wooda Barn V2

Wooda Barns Kings Nympton, Umberleigh, Devon. EX37 9EY A beautifully presented barn conversion offering spacious living accommodation with separate Grade II listed cottage, outbuildings, gardens and land, in all extending to approximately 3 acres. Kings Nympton: 0.5 miles ● South Molton: 6 miles ●Barnstaple: 17 miles ●Exeter: 27 miles (all distances are approximate) ● Vaulted Living/Dining Room ● Kitchen ● Si8ng Room , Utility 9 Office , 4 Bedrooms , 1 Bathrooms , 1 Bedroom Co=age , Outbuildings , Gardens 9 5and • Immaculately presented 4 bedroom family home • 1 bedroom holiday cottage • Near to the popular village of Kings Nympton • Outbuildings • Paddocks, fruit cage and fruit trees • Swimming pool • Sizeable driveway A parking for a number of cars • In all, about 3 acres Geoffrey Clapp Associates 10 Broad Street South .olton Devon EX36 3AB Tel: 01769 571111 Email: infoCgeoffreyclappassociates.com Location The popular and award winning village of Kings Nympton, which is set in the beautiful Devonshire countryside is a short distance away from the property and offers a well renowned public house along with a primary school, village hall and church. The property occupies a convenient position due to its close pro(imity to the train station at Kings Nympton providing good transport links to Barnstaple and E(eter via the Tarka 5ine and good transport links to further afield. The large village of Chulmleigh is approximately 4 miles to the North and provides everyday essentials: shops, dentists, doctors, restaurants, primary and secondary education. The market town of South Molton with its popular twice weekly panier market offers a further range of shops, social and educational amenities. -

Building Advisory Notes(PDF, 218KB)

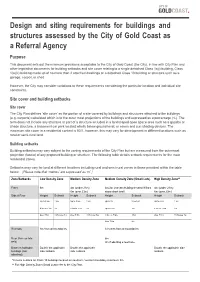

Design and siting requirements for buildings and structures assessed by the City of Gold Coast as a Referral Agency Purpose This document sets out the minimum provisions acceptable to the City of Gold Coast (the City), in line with City Plan and other legislative documents for building setbacks and site cover relating to a single detached Class 1a(i) building, Class 1(a)(ii) building made up of no more than 2 attached dwellings or a detached Class 10 building or structure such as a garage, carport or shed. However, the City may consider variations to these requirements considering the particular location and individual site constraints. Site cover and building setbacks Site cover The City Plan defines ‘site cover’ as the portion of a site covered by buildings and structures attached to the buildings (e.g. carports) calculated which is to the outer most projections of the buildings and expressed as a percentage (%). The term does not include any structure or part of a structure included in a landscaped open space area such as a gazebo or shade structure, a basement car park located wholly below ground level, or eaves and sun shading devices. The maximum site cover in a residential context is 50%, however, this may vary for development in different locations such as rural or semi-rural land. Building setbacks Building setbacks may vary subject to the zoning requirements of the City Plan but are measured from the outermost projection (fascia) of any proposed building or structure. The following table details setback requirements for the main residential zones. -

Higher Barn Farm

Higher Barn Farm The Farm is 19.41 Acres and 7.8 hectares set on a north facing field with magnificent views towards the Quantock Hills, Exmoor and the Welsh Brecon Beacon. The soil is silty clay loam, with almost 5% organic matter and a high level of Microbial activity. It is made up of two fields. The small farm has been farmed industrially for cereal crops via contractors for some years. The farm is just inside the Exmoor National Park area. Cerys, Amer, Bob and Anne are living there as an extended multi generational family with the two children Olive and Oak, and two further brothers and their families that might join in the project. The overall aim of the farm is to create a place where the whole family can live sustainably, where the children can be raised to learn about food and crafts. Whilst the aim is not to be 100% self sufficient the family would like to primarily provide for themselves and then sell surplus, and added value food like bread, and run courses to generate an income. This report and drawing is to suggest how the farm can be developed and managed to create a sustainable and abundant home, and livelihood for the family and for many other creatures. The Functions of the Farm have been identified as; To produce food To produce craft materials To produce fuel crops To be a learning centre for Ecology and regenerative agriculture and “Field to Fork courses” To generate income To provide a safe space for the family To support biodiversity To sequester carbon and be resilient in the face of climate change For play and recreation of the whole family THE SOIL The soil is a silty clay loam, with almost 5% organic matter. -

PERGOLAS 44 Design a Wood Pavilion 8 Urbana Vinyl Pergola

p e r g o l a s pav i l i o n s g a z e b o s 1 1 1 Contents 3 Living Our Values 36 Vinyl Pavilion Gallery 4 It’s Your Choice 38 Wood Pavilion Gallery 42 Design a Vinyl Pavilion PERGOLAS 44 Design a Wood Pavilion 8 Urbana Vinyl Pergola 10 Outback Wood Pergola GAZEBOS 12 Mendoza Wood Pergola 48 Vinyl Octagon Gazebo 14 Riviera Wood Pergola 50 Vinyl Oblong Gazebo 16 Alcove Wood Pergola 52 Vinyl Rectangular Gazebo 18 Vinyl Pergola Gallery 54 Wood Octagon Gazebo 20 Wood Pergola Gallery 56 Wood Oblong Gazebo 22 Design a Vinyl Pergola 58 Wood Rectangular Gazebo 23 Design a Wood Pergola 60 Gazebo Gallery 62 Vinyl Gazebo Standard Features PAVILIONS 63 Wood Gazebo Standard Features 26 Victoria Vinyl Pavilion 64 Design a Gazebo 28 Hampton Wood Pavilion 66 Accessories 30 Cascade Wood Pavilion 32 Breckenridge Wood Pavilion 34 Prairie Wood Pavilion Kit 2 Living Our Values At Berlin Gardens, our first goal is to bring honor and glory to our creator God in everything we do. We do this by manufacturing the highest quality products, delivering our products on time and going beyond your expectations with our customer service. All of this starts by living by our Core Values of honesty, efficiency, attitude, respect and trust. We not only say this, but we believe it. We hope our products help you take life outdoors™. –The Yoder Family 2 It’s Your Choice Classic, Carefree Vinyl Durable and beautiful, vinyl requires very little attention. Regular cleaning with a mild dish detergent or similar product is normally all that’s required to keep your structure looking its best. -

Western Timber Frame™ SCAPE

Made by: Western Timber Frame™ SCAPE TM ® The Ultimate Pergola & Pavilion Guide Everything you wanted to know about: Pergolas • Pavilions • Arbors • Trellises & More Coauthored by: Steven Bunker & Marilynn Thompson SCAPE TM ® Table of Contents Coauthored by: Steven Bunker and Marilynn Thompson Ultimate Pergola and Pavilion Guide Table of Contents ------------------------------ 6 What is a Pergola? ----------------------------- 8 What are Pavilions and Gazebos? ------------ 9 What is an Arbor or Trellis? ------------------ 10 Other Structures ----------------------------- 11 The Dovetail Difference™ -------------------- 12 Benefits of the Dovetail Difference™ --------- 14 Conventional Timber Framing --------------- 15 What makes us different -------------------- 16 Features and Benefits ----------------------- 17 Heavy Timber Kits ---------------------------- 18 Douglas Fir -------------------------------- 19 Douglas Fir Cont... Free Of Heart --------- 20 Vinyl --------------------------------------- 21 Aluminum ---------------------------------- 21 Customized Design --------------------------- 22 Choose your Style ---------------------------- 23 Tuscany Style -------------------------------- 26 Southwest Style ------------------------------ 26 ShadeScape™ series -------------------------- 27 Attached Kits - Extend your Home ---------- 38 Standard Options ----------------------------- 39 Color Selection ------------------------------- 49 Concept to Creation -------------------------- 76 Meet your Design Manager ------------------ 77 3D -

DIY Pergola Guide

DIY Pergola Guide Planning your Project Easy Step by Step Guide Simple Illustrations Maintainence The specifications contained within this brochure are for guideline purposes only. For further information contact a registered consulting engineer and or your local shire council. By following a straight forward programme you can build an attractive and long lasting pergola with the minimum of effort and using only a few basic wood-working tools. Tanalised® timber is the ideal material for all garden structures. Strong yet light and easy to handle it is pressure treated with either Tanalith® or Vacsol® wood preservative to give it life time durability. Planning your Project General Hints: When you have planned your pergola it is advisable to consult your local council to ensure the structure conforms to local government regulations. Refer to local government regulations for requirements regarding pergola’s. It is strongly recommended that a competent professional builder be engaged to construct pergola’s. It is also important to make sure that the pergola does not interfere with existing drainage, plumbing or electricity services. Where footings are in proximity to council sewer and or stormwater it may be necessary to complete a build over or near a sewer or stormwater application. Check with your local shire council, certifier or engineer for further details. Timber Selection Guide: Hazard Typical Uses Tools checklist: Class Tape measure, Square, Decking, fencing, cladding, fascia, H3 window joinery, exterior structural Pencil timber -

Zoning Ordinance County of Riverside

/f ZONING ORDINANCE COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE ORDINANCE NO. 348 AS AMENDED SEPTEMBER 22, 1960 ""Kg? TABLE OF CONTENTS Article Page I Intent and Purposes 1 II (Reserved for future legislation) 1 III M-3 Zone (Regulated Industrial) 1 IV Zoning Districts - Official Zoning Plans 4 V Zone Districts 5 VI R-l Zone (One Family Dwellings) - 6 Via R-l A Zone (One Family Dwellings - Mountain Resort) 7 VII R-2 Zone (Multiple Family Dwellings) 7 Vila R-2A Zone (Limited Multiple Family Dwellings) 7 VIII R-3 Zone (General Residential) 8 Villa R-3A Zone (General Residential - Mountain Resort) - 8 IX C-l Zone (General Commercial) - 8 IXa C-2 Zone (Limited Commercial) - 9 X C-P Zone (Restricted Commercial) 9 Xa I-P Zone (Industrial Park) - 10 XI M-l Zone (Light Manufacturing) 13 XIa M-4 Zone (Limited Industrial) 14 XII M-2 Zone (Heavy Industrial) 14 XIII A-l Zone (Light Agriculture) 15 XIV A-2 Zone (Heavy Agriculture) 17 XV W Zones - (Watercourse, Watershed, Conservation, and Recreational Areas). W-l Zone (Watercourse Areas). W-2 Zone (Watershed, Conservation, and Recreational Areas) 18 XVI I Zone (Interim) 19 XVII Public Functions or Uses 21 XVIII General Provisions 21 XIX Variances - 24 XX Amendments and Change of Zone 26 XXI Definitions 26 XXII Enforcement, Legal Procedure and 30 Penalties - 31 XXIII Validity 31 XXIV Authentication - ORDINANCE NO. 348 An Ordinance providing for the creation and establishment of zones In the unincorporated area of the County of Riverside, defining, classifying, restricting and regulating land uses and pre scribing area requirements and classes of uses of buildings, structures, improvements and premises in the several zones; repealing Ordinances No. -

DESIGN REVIEW BOARD City Hall Conference Room 214 W

CITY OF LITCHFIELD PARK Regular Meeting Thursday, June 7, 2018 7:00 p.m. DESIGN REVIEW BOARD City Hall Conference Room 214 W. Wigwam Boulevard Litchfield Park, Arizona 85340 Members of the Litchfield Park Design Review Board may attend either in person or by telephone conference call. I. Call to Order II. Pledge of Allegiance III. Call to the Community Information (This is the time for citizens who would like to address the Commission on any non-agenda item. Action taken as a result of public comment will be limited to asking Staff to review the matter, asking that the matter be put on a future agenda, or responding to criticism.) IV. Business A. Design Plans for an Addition/Remodel Proposed for 4869 Village Parkway Information Action Discussion and possible action on the design plans for an addition/remodel proposed for 4869 Village Parkway. B. Design Plan for a New Pergola and Rear Yard Wall Proposed for 390 E. Bird Information Lane Action Discussion and possible action on the design plans for a new pergola and rear yard wall proposed for 390 E. Bird Lane. C. Design Plans for an Addition/Remodel Proposed for 1069 Vista Verde Information Action Discussion and possible action on the design plans for an addition/remodel proposed for 1069 Vista Verde. D. Design Plans for a New Custom Home Proposed for 508 E. Fairway Drive Information Action Discussion and possible action on the design plans for a new custom home proposed for 508 E. Fairway Drive. E. Design Plans for a Roof Mounted Solar Panel Installation Proposed for 964 Information Castillo Drive East Action Discussion and possible action on the design plans for a roof mounted solar panel installation proposed for 964 Castillo Drive East. -

No Meeting Agenda There Is No Agenda Available for This Meeting

1. No Meeting Agenda There is no agenda available for this meeting. Please view the minutes. 2. Consent, Consent With Conditions Documents: 26 GOLDFINCH DR- OUTDR SHWR.PDF 31 WOODBURY LN - REV 3161 RFWLK CLR CHG.PDF 17 CLARENDON ST- RETAINING WALL.PDF 3. Consent, Consent With Conditions Documents: 1 BOUCHER WAY - GARAGE ADDITION.PDF 1 DOC RYDER DRIVE - SHED.PDF 1 FALMOUTH AVE - SHED.PDF 2 MAYFLOWER CIRCLE - POOL AND HARDSCAPE.PDF 3 WEYMOUTH ST - FENCE.PDF 4 BATHING BEACH ROAD - REMOVE AWNING.PDF 5 GARDNER PERRY LANE - ADD SHED DORMER.PDF 5 GREY LADY LANE - REV 01-2564 WINDOW CHNG.PDF 5 OLD MILL COURT - REV 3035 FENES ODS.PDF 6 DEER RUN ROAD - REV 12-2638 MOVE ON.PDF 6 HEDGE ROW - POOL AND HARDSCAPE.PDF 6 WOODLAND DRIVE - REV 03-3250 RELOCATE POOL.PDF 8 BUNKER HILL ROAD - ARBOR W GATE.PDF 8 MACLEAN LANE - POOL AND HARDSCAPE.PDF 10R GOLFVIEW DRIVE - POOL AND HARDSCAPE.PDF 11.5 GRAY AVE - SHED.PDF 13 NEW MILL ST - REV 12-2502 PORCH ROOF.PDF 15 ELLENS WAY - HARDSCAPE.PDF 15 PLEASANT STREET - DOOR COLOR CHANGE.PDF 16 LYONS LANE - POOL AND HARDSCAPE.PDF 19A W CHESTER ST - FENCE.PDF 20 GARDNER ST - ROOF CHANGE.PDF 20 SCONSET AVE - SPA AND HARDSCAPE.PDF 22 MILK STREET - OUTDOOR SHOWER.PDF 24 AMELIA DRIVE - SHED MOVE ON FROM 8 CRESTWOOD.PDF 25B WASHINGTON ST - LK PORCH AND DOOR COLOR.PDF 26 MONOMOY-RMVE SOLAR - ROOF CHANGE.PDF 26 PINE CREST DRIVE - PATIO AND FIREPIT.PDF 27 BREWSTER ROAD - GARAGE.PDF 27 BREWSTER ROAD - SHED.PDF 29 COFFIN ST- ODS EXPAND DECK.PDF 30 DEVON ST - SHED.PDF 32 CHUCK HOLLOW ROAD - 2ND DWELLING.PDF 33 NONANTUM AVE - SPA