College and Research Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SRRT 6I a Publicationof the Socialresponsibilities Round T of the Americanlibrary Association

SRRT 6I A Publicationof the SocialResponsibilities Round T of the AmericanLibrary Association June1990 Number96 lssN0749-1670 INTERNATIONAL REI.ATIONS COMMITTEE AND COMMITTEEON ISRAELICENSORSHIP CAMPAIGN SOUTHAFRICA by DavidL. Williams,Coordinator, Committee on lsraeli Censorship The Executive Board of the American Library Associationhas transmitted to the InternationalRelations As the lsraelimilitary occupation of the West Committee (lRC) the report authored by Robert Bank and Gaza enters its 23rd year, Palestinians Wedgeworthand ElizabethDrew on their trip to South continueto resistthe occupationregime and to press Africa on behalf of the American Association of theirdemands for self-determinationand basicpolitical Publishersand the Fundfor FreeExpression. [For more freedoms. As the death toll continuesto mount,this on the report,entitled 'The Starvationof Young Black thornyissue has come up withinthe AmericanLibrary Mirds: The Effectof Book Boycottsin SouthAfrica,' see Associationthrough the campaign launchedby the AmericanLibraries Jan. 1990,p. 9.1 The IRC will hold newly-formedCommittee on lsraeli Censorship (ClC) hearings at the Al-A Annual Conference in Chicago [not affiliatedwith the AmericanLibrary Association]. on Sunday, June 24 at 4:30 p.m. at the Chicago Thisis not the firsttime that the issuehas been Hihon. debatedin Al-A. In 1984a letterfrom a librarianwho is Personswho are interestedin commentingon also a prime mover in the current campaignresulted in the repoft are invited to attend the hearings. Please the formation of a joint subcommittee of the indicateyour interestby sending a notice to Robert lnternationalRelations Committee (lRC) and the Doyle,the IRC liaison,at ALA headquartersin Chicago lntellectualFreedom Committee (lFC) to look into or telephone him at 1-800-545-2433to indicate your allegationsof lsraelicensorship and reportback at the intentionof speakingat the hearings.Those who opt to June 1984ALA conference. -

Ideas for Celebrating Banned Books Week

Ideas for Celebrating Banned Books Week Banned Books Week is an annual national event celebrating the freedom to read and the importance of the First Amendment. (The 2015 celebration will be held from September 27 – October 3, 2015.) Banned Books Week highlights the benefits of free and open access to information while drawing attention to the dangers of censorship by spotlighting actual or attempted banning of books throughout the United States. The ideas below can be used to celebrate Banned Books Week, or integrated throughout the school year to ensure student understanding of the freedom to read. (For more information about Banned Books Week, go to http://www.bannedbooksweek.org/) For lesson plans on teaching about banned books, related themes, and numerous additional topics, visit the Carolina K-12’s (www.carolinak12.org) Database of K-12 Resources at: k12database.unc.edu Creation of this curriculum was funded by the Freedom to Read Foundation’s Judith F. Krug Memorial Fund. For more information about the Freedom to Read Foundation, go to http://www.ftrf.org/. Banned Books Trading Cards Each year, the Chapel Hill Public Library celebrates Banned Books Week by hosting an art contest in which local artists submit small scale (trading card size) works of art inspired by a banned/challenged book or author. The cards contain interpretive artwork on the front and the artist’s statement and information about the highlighted book and/or author on the back. • Utilize the cards as discussion pieces for learning about the freedom to read: Provide -

Racism and “Freedom of Speech”: Framing the Issues

Al Kagan Editorial Racism and “Freedom of Speech”: Framing the Issues The production and distribution of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom’s 1977 film was one of the most controversial and divisive issues in ALA history. The Speaker: A Film About Freedom was introduced at the 1977 ALA Annual Conference in Detroit, and was revived on June 30th, 2014, for a program in Las Vegas titled, “Speaking about ‘The Speaker.’” ALA Council’s Intellectual Freedom Committee (IFC) developed the program, which was cosponsored by the Freedom to Read Foundation (FTRF), the Library History Round Table and the ALA Black Caucus (BCALA). 4 Some background is necessary for context. This professionally made 42- minute color film was sponsored by the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom in 1977 and made in virtual secret without oversight by the ALA Executive Board or even most of the Intellectual Freedom Committee members. In fact, requests for information about the film, for copies of the script from members of these two bodies were repeatedly rebuffed. Judith Krug (now deceased), Director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom, was in charge with coordination from a two- member IFC subcommittee and ALA Executive Director Robert Wedgeworth. The film was made by a New York production company, and was envisioned by Krug as an exploration of the First Amendment in contemporary society. The film’s plot is a fictionalized account of real events. A high school invites a famous scientist (based on physicist and Nobel prizewinner William Shockley) to speak on his research claiming that black people are genetically Al Kagan is Professor of Library Administration and African Studies Bibliographer Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. -

Vol. 37, No. 2 June 2012

FREEDOM TO READ FOUNDATION NEWS 50 EAST HURON STREET, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60611 PHONE (312) 280-4226 www.ftrf.org ● [email protected] ● www.ftrf.org/ftrfnews Barbara M. Jones, Executive Director ● Kent Oliver, President Vol. 37, No. 2 June 2012 Utah: Fed. Judge rules for Inside this issue of FTRF News… • Eight Krug Fund Banned Books Week grants FTRF in Net content case announced, p. 2 • FTRF trustee election results, p. 3 On May 16, U.S. District Judge Dee Benson entered an • order in favor of FTRF and our co-plaintiffs in Florence Steven Booth is 2012 Conable conference v. Shurtleff, the long-standing suit concerning a Utah law scholar, p. 4 • that would have criminalized the posting of content con- Michael Bamberger named Roll of Honor stitutionally protected for adults on generally-accessible receipient, p. 5 websites. The court further held that those publishing constitutionally-protected material on the Internet are not required by law to rate or label that material. “Member Get a Member”: Media Coalition’s Michael Bamberger, lead counsel for Help make FTRF stronger! the plaintiffs (and recipient of FTRF’s 2012 Roll of By Barbara M. Jones, Executive Director Honor Award, see p. 5) worked out an agreement with the state attorney general the law’s implementation. Per As part of our ongoing initiative to increase the the agreement, only those who intentionally send membership of the Freedom to Read Foundation, in "harmful to minors" material to a minor having furtherance of our strategic plan, I’m pleased to announce negligently failed to determine the age of the recipient a new version of a tried-and-true program: “Member Get can be prosecuted under the law. -

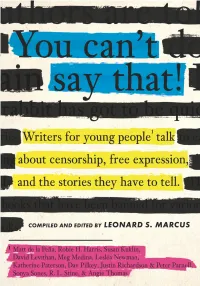

Read a Sample Chapter

YOU CAN’T SAY THAT YOU CAN’T SAY THAT Writers for Young People Talk About Censorship, Free Expression, and the Stories ey Have to Tell COMPILED AND EDITED BY LEONARD S. MARCUS Text copyright © by Leonard S. Marcus Photographs copyright © by Sonya Sones except: page , photograph copyright © by Randolph T. Holhut; page , photograph copyright © by Kai Suzuki; page , photograph copyright © by Justin Richardson (top); photograph copyright © by Peter Parnell (bottom) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number pending ISBN ---- CCP Printed in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China is book was typeset in Minion Pro. Candlewick Press Dover Street Somerville, Massachusetts www.candlewick.com FOR MY UNCLE ABE FREEDMAN, who owned one of the fi rst copies of Ulysses to reach New York and who always said what he pleased IN MEMORY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ix MATT DE LA PEÑA 1 ROBIE H. HARRIS 17 SUSAN KUKLIN 41 DAVID LEVITHAN 61 MEG MEDINA 75 LESLÉA NEWMAN 89 KATHERINE PATERSON 107 DAV PILKEY 126 JUSTIN RICHARDSON AND PETER PARNELL 142 SONYA SONES 159 R. L. STINE 173 ANGIE THOMAS 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 203 SOURCE NOTES 205 SELECTED READING 209 INDEX 213 INTRODUCTION censor: to examine in order to suppress or delete anything considered objectionable —Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary It’s hard being a person. We all know that. —from “Runaway Teen” by William Staff ord At the age of ten, it thrilled me to learn that history had once been made in Mount Vernon, New York, the quiet, tree- lined suburban town where my parents had chosen to raise their family. -

Lisnews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly Dan Kleinman

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons West Bend Community Memorial Library Archive of Challenges to Library Materials (Wisconsin), 2009 4-20-2009 LISNews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly Dan Kleinman Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/west_bend_library_challenge Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Kleinman, Dan, "LISNews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly" (2009). West Bend Community Memorial Library (Wisconsin), 2009. 333. https://dc.uwm.edu/west_bend_library_challenge/333 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Bend Community Memorial Library (Wisconsin), 2009 by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Monday, April 20, 2009 LISNews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly LISNews is an excellent news source for those interested in libraries. In addition to its daily activities, it podcasts weekly on library issues. Unwittingly, but justifiably, it mocked the American Library Association's [ALA] former de facto leader in the very publication dedicated to that leader. The most recent podcast was "dedicated to recently departed freedom crusader Judith Krug." See "LISTen: An LISNews.org Podcast -- Episode #68," by Stephen Michael Kellat, LISNews, 19 April 2009. Judith Krug was the de facto leader of the ALA for about 40 years. Thanks in part to her ACLU heritage, she single-handedly changed libraries so they no longer protect children from inappropriate material like they used to. For example, she alone created "Banned Books Week," ostensibly to decry censorship, even though no books have been banned in the USA for half a century and it is nearly impossible to do so now for reasons that have nothing to do with the ALA. -

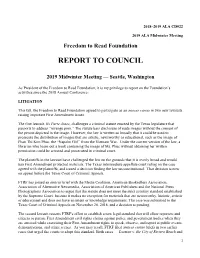

Freedom to Read Foundation

2018–2019 ALA CD#22 2019 ALA Midwinter Meeting Freedom to Read Foundation REPORT TO COUNCIL 2019 Midwinter Meeting — Seattle, Washington As President of the Freedom to Read Foundation, it is my privilege to report on the Foundation’s activities since the 2018 Annual Conference: LITIGATION This fall, the Freedom to Read Foundation agreed to participate as an amicus curiae in two new lawsuits raising important First Amendment issues. The first lawsuit, Ex Parte Jones, challenges a criminal statute enacted by the Texas legislature that purports to address “revenge porn.” The statute bars disclosure of nude images without the consent of the person depicted in the image. However, the law is written so broadly that it could be used to prosecute the distribution of images that are artistic, newsworthy or educational, such as the image of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the “Napalm Girl” from the Vietnam War. Under the current version of the law, a librarian who loans out a book containing the image of Ms. Phuc without obtaining her written permission could be arrested and prosecuted in criminal court. The plaintiffs in the lawsuit have challenged the law on the grounds that it is overly broad and would ban First Amendment protected materials. The Texas intermediate appellate court ruling on the case agreed with the plaintiffs, and issued a decision finding the law unconstitutional. That decision is now on appeal before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. FTRF has joined an amicus brief with the Media Coalition, American Booksellers Association, Association of Alternative Newsmedia, Association of American Publishers and the National Press Photographers Association to argue that the statute does not meet the strict scrutiny standard established by the Supreme Court, because it makes no exception for materials that are newsworthy, historic, artistic or educational and does not have an intent or knowledge requirement. -

2008 Box 1: Benton Foundati

6/1/6 Office for Intellectual Freedom Director Office for Intellectual Freedom Subject Files, 1965 - 2008 Box 1: Benton Foundation, 1988 Bibliographies, 1970, 1975, 1977 Edwin Castagna’s Response to an Article in “Let Freedom Ring” about Communist Influence in ALA, 1965 Dealing with Complaints about Resources, 1978 Intellectual Freedom Caucus Announcement, 1973 LeRoy C. Merritt Humanitarian Fund Fact Sheets, 1973 Policies, Pamphlets, Resolutions, Guidelines, 1969-85 Program Planning Workbook, 1975 Promotional Literature and Materials Price Lists, 1969, 1978-81 The Speaker (1977 film): Materials, 1977 Contract and Treatments, 1975 Film Chronology, 1975-77 Subject Treatment, 1976 The Speaker (OIF-IFC), 1977-78 Box 2: The Speaker: A Film About Freedom, Discussion Guide, 1977 The Speaker, Brochure The Speaker, Evaluation Forms, 1977 [4 folders] Box 3: Standing Committee on Review, Inquiry, and Mediation (SCRIM) [RESTRICTED] 1987 - 93 [4 folders] Strategic Long Range Planning, 1985 [2 folders] ALA Planning Document, April 1986 ALA Planning Committee Meeting, October 1986 Strategic Long Range Planning (SLRP), Priority Area C: Intellectual Freedom, 1986 SLRP, 1987-88 [2 folders] SLRP Planning Meeting, August 1987 ALA in Action: A Current Inventory by Priority Areas, Sept 1987 SLRP Planning Documents: Observation and Strategies, June 1988 [2 folders] SLRP Planning Documents: Observation and Strategies, 1988 aka 1988-89 Council Document #5 Office for Library Personnel Resources, Accountability Review, 1988 SLRP, Memo and Statements, Intellectual -

6/3/13 Office of Intellectual Freedom Publications Audiovisual File, 1974-2009

6/3/13 Office of Intellectual Freedom Publications Audiovisual File, 1974-2009 Box 1: Audio recordings It Can Happen Here, 1975 (slide presentation with audiocassette) Freedom in America 1977 (2 filmstrips, 2 audio cassettes, a slide show, and a discussion guide on freedom of expression) Colloquium on School and School Library Censorship and Litigation, 1981 (12 magnetic audio tapes) Pornography on the Internet: A New Reality, AALL Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, 2001 (audiocassette) Video recordings Dave Baum Media Training for Judith Krug (2 videocassettes) Tell It Like It Is! On censorship of children’s books with Judy Blume & others (videocassette, 15 minutes) PEN Awards Ceremony, 2003 (videocassette) The Open Mind, Host: Richard D. Heffner, guest: Judith Krug, “Intellectual Freedom and America’s Libraries”, 2004 (videocassette) Box 2: “Books on Trial”, Camera at Large series, WCAU-TV Philadelphia, Charles Shaw, moderator, discussion of Tropic of Cancer censorship, c. 1961 (film cannister) The Speaker, 1977 (2 film cannisters) Box 3: “Controlling the Confrontation,” 1989 and Interviews with Barney Rossett and Allen Ginsberg, VHS “Reading Your Rights” and “Of Rights and Wrongs, ” VHS “The Speaker” and “Caught in the Crossfire,” VHS “Presentation of Karen Schneider on Internet Filtering,” 1998 and Presentations of Anne Kappler on the Internet and the Law, VHS, 1998 (two folders) “Tell It Like it Is!” ca. 2000s and “Child Pornography?” VHS, 2000 “Live Free,” DVD, 2004 Acapulco 7-8-2000 (two parts) and Ethics, 6-26-2006 (two parts), cassette Memorial-Judith Krug, 2009 (DVD has been digitized) Academic Freedom Workshop, David Staver, “Community Relations,” March 18, 1978 Academic Freedom Workshop, Bill North and Pat Ferguson, “The Legal Scene and Education,” March 18, 1978 Academic Freedom Workshop, Midge Miller and Charlotte Zietlow, “The Legislative Process,” March 18, 1978 “Are You Being Screwed Electronically?”, COPE, (two cassettes), 1987 “Citizens for Decency Through Law,” Raymond P. -

ALKI: the Washington Library Association Journal

ALKI: The Washington Library Association Journal July 1997 Volume 13, Number 2 Table of Contents Features Wired and Inspired! WLA/OLA Conference, Portland Awards Funny Bid'nis, a conversation with Molly Ivins Jennifer Reynolds, The Evergreen State College The Ethics of Affordability: Community, Compassion, and the Public Trust Theodore Roszak, California State University Cultural Rage and Computer Literacy, a response to Theodore Roszak Michelle Kendrick, Washington State University Outsource the Routines, Retain the Expertise Jim Dwyer, Chico State University Columns Upfront - Getting Connected--On An Equal Footing Joan Weber, Yakima Valley Community College From the Editor - Use the Filter You Were Born With Vince Kueter, Alki Editor WLA Communiqué - Legislative Day was a Rousing Success! The Vertical File - News from around Libraryland Focus on Youth - Collecting Memories and Remembering Collections Thom Barthelmess, Spokane County Library District Your Best Face - Washington Libraries Respond Creatively to Internet Access Issues Mary Kelly, Sno-Isle Library System Who's On First - Unrestricted Internet Access at Public Libraries...Or Not? Tom Reynolds, Sno-Isle Library System Only Connect - Don't Overlook the Human Factor James J. Kopp, University of Portland I'd Rather Be Reading - My Own Private "Dui" Nancy Pearl, Seattle Public Library VERSO - The Primal Shush--Don't Fight It! Cameron Johnson, Everett Public Library ALKI: The Washington Library Association Journal July 1997 Vol 13 No 2 Awards WLA Awards Martha Parsons WSU Energy Program Library President's Award Michael Hedges Pierce County Library Merit Award Outstanding Performance in a Special Area (awarded posthumously) Michael Schuyler Kitsap Regional Library Merit Award Advances in Library Services Phelps Shepard Mid-Columbia Library Merit Award Advances in Library Services Laura M. -

Social Media Privacy: a Rallying Cry to Librarians

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY School of Law 2015 Social Media Privacy: A Rallying Cry to Librarians Sarah Lamdan CUNY School of Law How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/52 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Social Media Privacy: A Rallying Cry to Librarians Sarah Shik Lamdan ABSTRACT As information technology advances at a rapid pace, librarians must take action to continue their traditional roles as champions of privacy and intellectual freedom into the digital age. So- cial media is quickly becoming a major source of information and center for information seek- ing, and librarians have an opportunity to promote and help shape social media policies that protect users’ privacy and assure that users can seek information without inhibition. This article recalls librarians’ historical privacy campaigns, investigates the impact of social media on pri- vacy, and offers librarians a plan for joining the social media user rights movement by advocat- ing terms-of-use agreements that protect information seekers. ocial media is the most prevalent Internet activity, overtaking even pornography as q1 the most popular online pastime (Fontecilla 2013). Social media has become people’s S primary source for news, opinions, and the human connection. It fosters social movements and catalyzes political change around the world. Facebook, Twitter, and other social media companies are quickly becoming ingrained in society as information portals. -

Your Library Campaign Launch Compilation Reel, TRT 4:50, VHS, C

12/3/63 Public Relations Publications Audiovisual Material, 1969-ca. 1970, 1977, 1984-1993, 1996-1999, 2003-2006 Box 1: @ Your Library Campaign Launch Compilation Reel, TRT 4:50, VHS, c. 2002 @ Your Library: “Cindylou, the Singing Librarian,” VHS Dub from SVHS Edit Master, 3/26/2002 @ Your Library “Teen Services,” VHS dub from SVHS Edit Master, 2/26/2002 9 Clips (with Betty Turock: Internet), 10:58, VHS, 5/15/1996 100th Anniversary, New York Public Library, 14:00, 6/4/95, VHS, 7/27/1995 1993 Summer Reading Club PSA, 0:30, VHS, 1993 AASL General Session, Portland, Oregon, 97:54, VHS, 4/18/97 Achieving Breakthrough Service in Libraries, VHS, 5/12/1994 [2 copies] Ad Council/Benton Foundation, Connect for Kids, “Parent Teacher Conference, “ 0:30; “Pouting Teacher,” 0:30, VHS, 3/5/1999 "Adult Basic Education Spots" Johnny Cash Award, 3/4" U-Matic, 20:15, n. d. The Agenda #157, Interview with the American Library President, VHS, n. d. ALA Annual Conference, Tape 1, Libraries Build Community, 7/8/2002, 10" Betacam SP ALA Atlanta Rally 1991, 1:01:35, VHS ALA Atlanta Rally 1991, 60:00, VHS, 4/26/95 “ALA/Barbara Ford,” 6 News Today, WDSU-TV (NBC) New Orleans, 5:30-7AM, 4:55,VHS, 1/8/1998 ALA, CBS Evening News, CBS Television Network, 6/16/2003, 6-7, 2:37; (ii) Live from the Headlines, CNN Cable Network, 6/16/2003, 7-9pm, 3:54, VHS ALA Demo Tape - computer catalog, 1/2" VHS, 10/29/82 ALA Goal 2000 - A Nation Connected, 2/20/1996 1/2" VHS Summit, Panel 1, 1:51:00 [2 copies] Panel 1B Panel 2, 1:40:00 Panel 3, 1:26:00, [2 copies] 6 audio cassettes Box