Pro Se Patrons in the Law Library: the Case for Privacy in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Director's Report

#EBD 12.35 ALA Executive Director’s Report to ALA Executive Board Prepared by Tracie D. Hall April 5, 2021 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ASSOCIATION UPDATES AND HIGHLIGHTS • ALA Leads Charge on Library Inclusion in American Rescue Plan Act • Membership Committee and Member Relationship Services Propose Membership Retention Strategy • ASGCLA Transition Update • National Library Week • First Widescale Study of Race and LIS workforce Retention • Select Division Events this Quarter • Human Resources/Staffing Update • Financial Update • Pivot Strategy Update • Draft Cross Functional Teams REPORTS OF ALA OFFICES AND UNITS • Chapter Relations Office • Communications And Marketing Office • Conference Services • Development • Governance Office • Information Technology (IT) • International Relations Office • Member Relations & Services • Office for Accreditation • Office for Diversity, Literacy And Outreach Services • Office for Intellectual Freedom • Public Policy and Advocacy • Public Programs Office • Publishing REPORT OF ALA DIVISIONS • American Association of School Librarians • Association of College And Research Libraries • Association For Library Service to Children • Core • Public Library Association • Reference And User Services Association • United for Libraries • Young Adult Library Services Association ASSOCIATION UPDATE The third quarter of FY21 finds the American Library Association busy launching key new programs designed to support libraries nationally that have been adversely impacted by reductions in funding even as their communities turn to them for increasingly urgent information access and digital connectivity needs; and unveiling new initiatives to ensure that the library workers who run them have expanded access to the educational resources, practitioner networks, data and tends analysis, and opportunities to apply for grants and individual financial support needed to ensure that their libraries and careers remain productive and impactful. -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

Saturday Issue 2 V2.Indd

Issue 2 ������������Seattle, WA Saturday, January 20, 2007 Highlights Klein to Present Curley SATURDAY Memorial Lecture oe Klein, senior writer for Seattle Sunrise Time magazine and au- Speaker Series Jthor of several best selling Transforming Yourself: books, will discuss “Islam, Iraq and the War on Terror” at the Reaching New Heights Eighth Annual Arthur Curley 8:00 - 9:00 a.m. Memorial Lecture today at 4:00 Washington State p.m. in the Washington State Convention and Trade Trade and Convention Center, Center, Room 6B/C Room 611-614. Klein’s provocative weekly column, “In the Arena,” covers Council Orientation national and international af- 8:00-10:00 a.m. fairs. He has written lengthy Sheraton Hotel portraits of Barack Obama, Metropolitan A John McCain and Tony Blair, to name a few. In 2004, Klein won ALA President Leslie Burger, right, and President-Elect Loriene Joe Klein Roy, left, cut the ribbon to open the exhibits as the ALA Board Presidential Candidates the National Headliner Award for best magazine column. Continued on page 4 looks on. Forum 11:00 am-12:00 p.m. Washington State Tracie D. Hall to Keynote Convention and Trade Center, Room 6B/6C King Celebration racie D. Hall, and the Black Caucus of the American ALA/FOLUSA Adult recently appointed Assis- Library Association (BCALA), Literature Spotlight Ttant Dean of the GLSIS the Association’s seventh an- 2:00-4:00 p.m. at Dominican University will nual sunrise celebration will be the keynote speaker at the honor the work and life of Dr. Washington State Dr. -

SRRT 6I a Publicationof the Socialresponsibilities Round T of the Americanlibrary Association

SRRT 6I A Publicationof the SocialResponsibilities Round T of the AmericanLibrary Association June1990 Number96 lssN0749-1670 INTERNATIONAL REI.ATIONS COMMITTEE AND COMMITTEEON ISRAELICENSORSHIP CAMPAIGN SOUTHAFRICA by DavidL. Williams,Coordinator, Committee on lsraeli Censorship The Executive Board of the American Library Associationhas transmitted to the InternationalRelations As the lsraelimilitary occupation of the West Committee (lRC) the report authored by Robert Bank and Gaza enters its 23rd year, Palestinians Wedgeworthand ElizabethDrew on their trip to South continueto resistthe occupationregime and to press Africa on behalf of the American Association of theirdemands for self-determinationand basicpolitical Publishersand the Fundfor FreeExpression. [For more freedoms. As the death toll continuesto mount,this on the report,entitled 'The Starvationof Young Black thornyissue has come up withinthe AmericanLibrary Mirds: The Effectof Book Boycottsin SouthAfrica,' see Associationthrough the campaign launchedby the AmericanLibraries Jan. 1990,p. 9.1 The IRC will hold newly-formedCommittee on lsraeli Censorship (ClC) hearings at the Al-A Annual Conference in Chicago [not affiliatedwith the AmericanLibrary Association]. on Sunday, June 24 at 4:30 p.m. at the Chicago Thisis not the firsttime that the issuehas been Hihon. debatedin Al-A. In 1984a letterfrom a librarianwho is Personswho are interestedin commentingon also a prime mover in the current campaignresulted in the repoft are invited to attend the hearings. Please the formation of a joint subcommittee of the indicateyour interestby sending a notice to Robert lnternationalRelations Committee (lRC) and the Doyle,the IRC liaison,at ALA headquartersin Chicago lntellectualFreedom Committee (lFC) to look into or telephone him at 1-800-545-2433to indicate your allegationsof lsraelicensorship and reportback at the intentionof speakingat the hearings.Those who opt to June 1984ALA conference. -

Ideas for Celebrating Banned Books Week

Ideas for Celebrating Banned Books Week Banned Books Week is an annual national event celebrating the freedom to read and the importance of the First Amendment. (The 2015 celebration will be held from September 27 – October 3, 2015.) Banned Books Week highlights the benefits of free and open access to information while drawing attention to the dangers of censorship by spotlighting actual or attempted banning of books throughout the United States. The ideas below can be used to celebrate Banned Books Week, or integrated throughout the school year to ensure student understanding of the freedom to read. (For more information about Banned Books Week, go to http://www.bannedbooksweek.org/) For lesson plans on teaching about banned books, related themes, and numerous additional topics, visit the Carolina K-12’s (www.carolinak12.org) Database of K-12 Resources at: k12database.unc.edu Creation of this curriculum was funded by the Freedom to Read Foundation’s Judith F. Krug Memorial Fund. For more information about the Freedom to Read Foundation, go to http://www.ftrf.org/. Banned Books Trading Cards Each year, the Chapel Hill Public Library celebrates Banned Books Week by hosting an art contest in which local artists submit small scale (trading card size) works of art inspired by a banned/challenged book or author. The cards contain interpretive artwork on the front and the artist’s statement and information about the highlighted book and/or author on the back. • Utilize the cards as discussion pieces for learning about the freedom to read: Provide -

Summer Reading Book Lists

BPL Teen Summer Reading Best of the Best List If you’re not sure what to read, check out the books on this list. The list includes some of the best books published over the last few years. Read one of these books to check off a space on your summer reading bingo sheet or earn five bonus points on your reading log. You might even find a new favorite author. The Buckeye Teen Book Award is an award entirely nominated and voted on by Ohio students. The 2021 nominees are: Be Not Far from Me by Mindy McGinnis Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo The Girl in the White Van by April Henry The Inheritance Games by Jennifer Lynn Barnes The Invincible Summer of Juniper Jones by Daven McQueen Scan to vote starting September 1 Scan to nominate a book for the 2022 award The Teens’ Top Ten is a teen choice list, where teens nominate and choose their favorite books of the previous year. Nominators are members of teen book groups from sixteen school and public libraries around the country selected by the Young Adult Library Services Association to participate. Teens are encouraged to read the nominees throughout the summer to prepare for the national Teens’ Top Ten vote, which will take place Aug. 15 – Oct. 12. The 10 nominees that receive the most votes will be named the official 2021 Teens’ Top Ten. All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson All the Stars and Teeth by Adalyn Grace Atomic Women by Roseanne Montillo The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes by Suzanne Collins The Betrothed by Kiera Cass The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person by Frederick Joseph The Bone Thief by Breeana Shields Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas Chain of Gold by Cassandra Clare Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo Dangerous Secrets by Mari Mancusi The Dark Matter of Mona Starr by Laura Gulledge. -

College and Research Libraries

The Library as a Marketplace of Ideas Ronald J. Heckart Since the late 1930s, intellectual freedom has been a central theme in the professional ethics of librarians. From it has come powerful and inspiring rhetoric, but also confusion and controversy. This paper traces librarianship's notions of intellectual freedom to a widely analyzed concept in law and political science known as the marketplace of ideas, and finds that taking this broad theoretical view of intellectual freedom offers some useful insights into its strengths and weaknesses as an ethical cornerstone of the profession. ntellectual freedom is a com So ingrained and self-evident is this pelling theme in the profes theme that relatively few librarians have sional ethics of librarians. It is felt the need to explore its philosophical expressed in fervent support origins or to examine rigorously the con for the free trade in ideas and in vigorous siderable literature that legal scholars opposition to censorship. The Library Bill and political theorists have developed of Rights and the Freedom to Read state on the topic. The professional literature ments are embodiments of this theme. on this subject is rather sparse. This arti The former states that "all libraries are cle attempts to remedy this situation by forums for information and ideas" and examining the profession's stance on "should provide materials and infor censorship and the free flow of informa mation presenting all points of view on tion in a broad context of political and current and historical issues."1 The lat legal theory. Specifically, the aim will be ter, a spirited and eloquent defense of to make the philosophical links between freedom of expression, proclaims that "it this stance and a concept in constitu is in the public interest for publishers tional law known as the marketplace of and librarians to make available the ideas. -

Racism and “Freedom of Speech”: Framing the Issues

Al Kagan Editorial Racism and “Freedom of Speech”: Framing the Issues The production and distribution of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom’s 1977 film was one of the most controversial and divisive issues in ALA history. The Speaker: A Film About Freedom was introduced at the 1977 ALA Annual Conference in Detroit, and was revived on June 30th, 2014, for a program in Las Vegas titled, “Speaking about ‘The Speaker.’” ALA Council’s Intellectual Freedom Committee (IFC) developed the program, which was cosponsored by the Freedom to Read Foundation (FTRF), the Library History Round Table and the ALA Black Caucus (BCALA). 4 Some background is necessary for context. This professionally made 42- minute color film was sponsored by the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom in 1977 and made in virtual secret without oversight by the ALA Executive Board or even most of the Intellectual Freedom Committee members. In fact, requests for information about the film, for copies of the script from members of these two bodies were repeatedly rebuffed. Judith Krug (now deceased), Director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom, was in charge with coordination from a two- member IFC subcommittee and ALA Executive Director Robert Wedgeworth. The film was made by a New York production company, and was envisioned by Krug as an exploration of the First Amendment in contemporary society. The film’s plot is a fictionalized account of real events. A high school invites a famous scientist (based on physicist and Nobel prizewinner William Shockley) to speak on his research claiming that black people are genetically Al Kagan is Professor of Library Administration and African Studies Bibliographer Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

Vol. 37, No. 2 June 2012

FREEDOM TO READ FOUNDATION NEWS 50 EAST HURON STREET, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60611 PHONE (312) 280-4226 www.ftrf.org ● [email protected] ● www.ftrf.org/ftrfnews Barbara M. Jones, Executive Director ● Kent Oliver, President Vol. 37, No. 2 June 2012 Utah: Fed. Judge rules for Inside this issue of FTRF News… • Eight Krug Fund Banned Books Week grants FTRF in Net content case announced, p. 2 • FTRF trustee election results, p. 3 On May 16, U.S. District Judge Dee Benson entered an • order in favor of FTRF and our co-plaintiffs in Florence Steven Booth is 2012 Conable conference v. Shurtleff, the long-standing suit concerning a Utah law scholar, p. 4 • that would have criminalized the posting of content con- Michael Bamberger named Roll of Honor stitutionally protected for adults on generally-accessible receipient, p. 5 websites. The court further held that those publishing constitutionally-protected material on the Internet are not required by law to rate or label that material. “Member Get a Member”: Media Coalition’s Michael Bamberger, lead counsel for Help make FTRF stronger! the plaintiffs (and recipient of FTRF’s 2012 Roll of By Barbara M. Jones, Executive Director Honor Award, see p. 5) worked out an agreement with the state attorney general the law’s implementation. Per As part of our ongoing initiative to increase the the agreement, only those who intentionally send membership of the Freedom to Read Foundation, in "harmful to minors" material to a minor having furtherance of our strategic plan, I’m pleased to announce negligently failed to determine the age of the recipient a new version of a tried-and-true program: “Member Get can be prosecuted under the law. -

Read a Sample Chapter

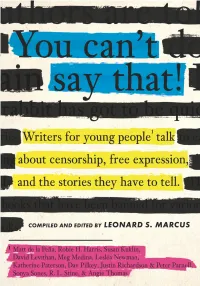

YOU CAN’T SAY THAT YOU CAN’T SAY THAT Writers for Young People Talk About Censorship, Free Expression, and the Stories ey Have to Tell COMPILED AND EDITED BY LEONARD S. MARCUS Text copyright © by Leonard S. Marcus Photographs copyright © by Sonya Sones except: page , photograph copyright © by Randolph T. Holhut; page , photograph copyright © by Kai Suzuki; page , photograph copyright © by Justin Richardson (top); photograph copyright © by Peter Parnell (bottom) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number pending ISBN ---- CCP Printed in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China is book was typeset in Minion Pro. Candlewick Press Dover Street Somerville, Massachusetts www.candlewick.com FOR MY UNCLE ABE FREEDMAN, who owned one of the fi rst copies of Ulysses to reach New York and who always said what he pleased IN MEMORY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ix MATT DE LA PEÑA 1 ROBIE H. HARRIS 17 SUSAN KUKLIN 41 DAVID LEVITHAN 61 MEG MEDINA 75 LESLÉA NEWMAN 89 KATHERINE PATERSON 107 DAV PILKEY 126 JUSTIN RICHARDSON AND PETER PARNELL 142 SONYA SONES 159 R. L. STINE 173 ANGIE THOMAS 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 203 SOURCE NOTES 205 SELECTED READING 209 INDEX 213 INTRODUCTION censor: to examine in order to suppress or delete anything considered objectionable —Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary It’s hard being a person. We all know that. —from “Runaway Teen” by William Staff ord At the age of ten, it thrilled me to learn that history had once been made in Mount Vernon, New York, the quiet, tree- lined suburban town where my parents had chosen to raise their family. -

Lisnews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly Dan Kleinman

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons West Bend Community Memorial Library Archive of Challenges to Library Materials (Wisconsin), 2009 4-20-2009 LISNews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly Dan Kleinman Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/west_bend_library_challenge Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Kleinman, Dan, "LISNews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly" (2009). West Bend Community Memorial Library (Wisconsin), 2009. 333. https://dc.uwm.edu/west_bend_library_challenge/333 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Bend Community Memorial Library (Wisconsin), 2009 by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Monday, April 20, 2009 LISNews Disses Judith Krug Unwittingly LISNews is an excellent news source for those interested in libraries. In addition to its daily activities, it podcasts weekly on library issues. Unwittingly, but justifiably, it mocked the American Library Association's [ALA] former de facto leader in the very publication dedicated to that leader. The most recent podcast was "dedicated to recently departed freedom crusader Judith Krug." See "LISTen: An LISNews.org Podcast -- Episode #68," by Stephen Michael Kellat, LISNews, 19 April 2009. Judith Krug was the de facto leader of the ALA for about 40 years. Thanks in part to her ACLU heritage, she single-handedly changed libraries so they no longer protect children from inappropriate material like they used to. For example, she alone created "Banned Books Week," ostensibly to decry censorship, even though no books have been banned in the USA for half a century and it is nearly impossible to do so now for reasons that have nothing to do with the ALA.