Experiences and Extrapolations from Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Nagasaki. an European Artistic City in Early Modern Japan

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Curvelo, Alexandra Nagasaki. An European artistic city in early modern Japan Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 2, june, 2001, pp. 23 - 35 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100202 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2001, 2, 23 - 35 NAGASAKI An European artistic city in early modern Japan Alexandra Curvelo Portuguese Institute for Conservation and Restoration In 1569 Gaspar Vilela was invited by one of Ômura Sumitada’s Christian vassals to visit him in a fishing village located on the coast of Hizen. After converting the lord’s retainers and burning the Buddhist temple, Vilela built a Christian church under the invocation of “Todos os Santos” (All Saints). This temple was erected near Bernardo Nagasaki Jinzaemon Sumikage’s residence, whose castle was set upon a promontory on the foot of which laid Nagasaki (literal translation of “long cape”)1. If by this time the Great Ship from Macao was frequenting the nearby harbours of Shiki and Fukuda, it seems plausible that since the late 1560’s Nagasaki was already thought as a commercial centre by the Portuguese due to local political instability. Nagasaki’s foundation dates from 1571, the exact year in which the Great Ship under the Captain-Major Tristão Vaz da Veiga sailed there for the first time. -

CORPORATE DIRECTORY (As of June 28, 2000)

CORPORATE DIRECTORY (as of June 28, 2000) JAPAN TOKYO ELECTRON KYUSHU LIMITED TOKYO ELECTRON FE LIMITED Saga Plant 30-7 Sumiyoshi-cho 2-chome TOKYO ELECTRON LIMITED 1375-41 Nishi-Shinmachi Fuchu City, Tokyo 183-8705 World Headquarters Tosu City, Saga 841-0074 Tel: 042-333-8411 TBS Broadcast Center Tel: 0942-81-1800 District Offices 3-6 Akasaka 5-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-8481 Kumamoto Plant Osaka, Kumamoto, Iwate, Tsuruoka, Sendai, Tel: 03-5561-7000 2655 Tsukure, Kikuyo-machi Aizuwakamatsu, Takasaki, Mito, Nirasaki, Toyama, Fax: 03-5561-7400 Kikuchi-gun, Kumamoto 869-1197 Kuwana, Fukuyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Saijo, Oita, URL: http://www.tel.co.jp/tel-e/ Tel: 096-292-3111 Nagasaki, Kikuyo, Kagoshima Regional Offices Ozu Plant Fuchu Technology Center, Osaka Branch Office, 272-4 Takaono, Ozu-machi TOKYO ELECTRON DEVICE LIMITED Kyushu Branch Office, Tohoku Regional Office, Kikuchi-gun, Kumamoto 869-1232 1 Higashikata-cho, Tsuzuki-ku Yamanashi Regional Office, Central Research Tel: 096-292-1600 Yokohama City, Kanagawa 224-0045 Laboratory/Process Technology Center Koshi Plant Tel: 045-474-7000 Sales Offices 1-1 Fukuhara, Koshi-machi Sales Offices Sendai, Nagoya Kikuchi-gun, Kumamoto 861-1116 Utsunomiya, Mito, Kumagaya, Kanda, Tachikawa, Tel: 096-349-5500 Yamanashi, Matsumoto, Nagoya, Osaka, Fukuoka TOKYO ELECTRON TOHOKU LIMITED Tohoku Plant TOKYO ELECTRON MIYAGI LIMITED TOKYO ELECTRON LEASING CO., LTD. 52 Matsunagane, Iwayado 1-1 Nekohazama, Nemawari, Matsushima-machi 30-7 Sumiyoshi-cho 2-chome Esashi City, Iwate 023-1101 Miyagi-gun, Miyagi -

Utility of the 2006 Sendai and 2012 Fukuoka Guidelines for The

® Observational Study Medicine OPEN Utility of the 2006 Sendai and 2012 Fukuoka guidelines for the management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas A single-center experience with 138 surgically treated patients Chih-Yang Hsiao, MD, Ching-Yao Yang, MD, PhD, Jin-Ming Wu, MD, Ting-Chun Kuo, MD, ∗ Yu-Wen Tien, MD, PhD Abstract This study aimed to evaluate the utility of the 2006 Sendai and 2012 Fukuoka guidelines for differentiating malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas from benign IPMN. Between January 2000 and March 2015, a total of 138 patients underwent surgery and had a pathologically confirmed pancreatic IPMN. Clinicopathological parameters were reviewed, and all patients were classified according to both the 2006 Sendai and 2012 Fukuoka guidelines. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used for identifying significant factors associated with malignancy in IPMN. There were 9 high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and 37 invasive cancers (ICs) in the 138 patients. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines for HGD/IC was 35.1%, 43.3%, 100%, and 85.4%, respectively. Of the 36 patients with worrisome features using the Fukuoka guideline, 7 patients had HGD/IC in their IPMNs. According to the multivariate analysis, jaundice, tumors of ≥3cm, presence of mural nodule on imaging, and aged <65 years were associated with HGD/IC in patients with IPMN. The Sendai guideline had a better NPV, but the Fukuoka guideline had a better PPV. We suggest that patients with worrisome features based on the Fukuoka guideline be aggressively managed. -

Learn from Japan's Earthquake and Tsunami Crisis

Learn from Japan’s Earthquake and Tsunami Crisis International Field Experience Spring 2018 TOHOKU TRIP BOOKLET Center for Public Service, Portland State University Contents What to pack? --------------------------------------- 2 Transportation --------------------------------------- 2-7 Cell phone -------------------------------------------- 7 WiFi ---------------------------------------------------- 7 Smartphone Apps ---------------------------------- 8 Restrooms -------------------------------------------- 8 Laundry ----------------------------------------------- 8 Tips ---------------------------------------------------- 8 Smoking and Alcohol ------------------------------ 9 Sales Tax --------------------------------------------- 9 Credit Cards ------------------------------------------ 9 Currency ---------------------------------------------- 10-11 Safety -------------------------------------------------- 11 In case of Emergency ------------------------------ 11 Phrases and Vocabulary -------------------------- 12-14 2 What to pack? While Japan offers most items found in the U.S., consider preparing the following items as listed below: ● Clothing: ○ Prepare for hot & humid weather Average temperature in the Tohoku region is ~72 with humidity. Bringing cotton or other lightweight clothing items for the trip is recommended. ℉ However, please remember to dress appropriately. Avoid open-toed shoes, exposing shoulders/chest, or anything above the knee when visiting shrines/memorial sites. Occasionally you will need to remove your shoes, -

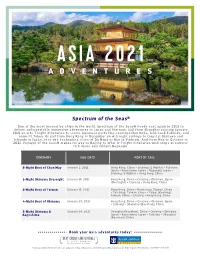

Spectrum of the Seas®

Spectrum of the Seas® One of the most innovative ships in the world, Spectrum of the Seas® heads east again in 2021 to deliver unforgettable immersive adventures to Japan and Vietnam. Sail from Shanghai starting January 2021 on 4 to 7 night itineraries to iconic Japanese ports like cosmopolitan Kobe, laid-back Fukuoka, and neon-lit Tokyo. Or sail from Hong Kong in December on 4-5 night sailings to tropical Okinawa and Ishigaki in Japan, or to the enchanting cities of Da Nang or Hue in Vietnam. And from May to October in 2021, Voyager of the Seas® makes its way to Beijing to offer 4-7 night itineraries with stops at culture- rich Kyoto and vibrant Nagasaki. ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 8-Night Best of Chan May January 2, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising (2 Nights) • Fukuoka, Japan • Kagoshima, Japan • Nagasaki, Japan • Cruising (2 Nights) • Hong Kong, China 5-Night Okinawa Overnight January 10, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising • Okinawa, Japan (Overnight) • Cruising • Hong Kong, China 5-Night Best of Taiwan January 15, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Kaohsiung, Taiwan, China • Taichung, Taiwan, China • Taipei (Keelung), Taiwan, China • Cruising • Hong Kong, China 4-Night Best of Okinawa January 20, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising • Okinawa, Japan • Cruising • Shanghai (Baoshan), China 5-Night Okinawa & January 24, 2021 Shanghai (Baoshan), China • Cruising • Okinawa, Kagoshima Japan • Kagoshima, Japan • Cruising • Shanghai (Baoshan), China Book your Asia adventures today! Features vary by ship. All itineraries are subject to change without -

Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Update Saturday, March 12, 2011

Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Update Saturday, March 12, 2011 Note: New content has been inserted in red, italicized, bold font. Overview A powerful 8.9-magnitude earthquake hit Japan on Friday (March 11) at 1446 local time (0546 GMT), unleashing massive tsunami waves that crashed into Japan’s eastern coast of Honshu, the largest and main island of Japan, resulting in widespread damage and destruction. According to the Government of Japan (GoJ) as of Saturday (March 12), at least 464 1 people have been reported dead and some 725 people are reported to be missing, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported. The GoJ’s chief spokesperson said the death toll could exceed 1,000. Local media put the death toll closer to 1,300 people. As initial assessments come in it is expected that the death toll will rise due to the extensive devastation along the coastline and majority of the casualties are likely to be the result of the tsunami. The earthquake sparked widespread tsunami warnings across the Pacific that stretched from Japan to North and South America. According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), the shallow quake struck at a depth of six miles (10 km) (20 km deep according to Japan’s Meteorological Agency), around 80 miles (125 km) off the eastern coast of Japan, and 240 miles (380 km) northeast of Tokyo. It was reportedly the largest recorded quake in Japan’s history and the fifth largest in the world since 1900. The quake was also felt in Japan’s capital city, Tokyo, located hundreds of miles from the epicenter and was also felt as far away as the Chinese capital Beijing, some 1,500 miles away. -

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN Arrive Yokohama: 0800 Sunday, January 27 Onboard Yokohama: 2100 Monday, January 28 Arrive Kobe: 0800 Wednesday, January 30 Onboard Kobe: 1800 Thursday, January 31 Brief Overview: The "Land of the Rising Sun" is a country where the past meets the future. Japanese culture stretches back millennia, yet has created some of the latest modern technology and trends. Japan is a study in contrasts and contradictions; in the middle of a modern skyscraper you might discover a sliding wooden door which leads to a traditional chamber with tatami mats, calligraphy, and tea ceremony. These juxtapositions mean you may often be surprised and rarely bored by your travels in Japan. Voyagers will have the opportunity to experience Japanese hospitality first-hand by participating in a formal tea ceremony, visiting with a family in their home in Yokohama or staying overnight at a traditional ryokan. Japan has one of the world's best transport systems, which makes getting around convenient, especially by train. It should be noted, however, that travel in Japan is much more expensive when compared to other Asian countries. Japan is famous for its gardens, known for its unique aesthetics both in landscape gardens and Zen rock/sand gardens. Rock and sand gardens can typically be found in temples, specifically those of Zen Buddhism. Buddhist and Shinto sites are among the most common religious sites, sure to leave one in awe. From Yokohama: Nature lovers will bask in the splendor of Japan’s iconic Mount Fuji and the Silver Frost Festival. Kamakura and Tokyo are also nearby and offer opportunities to explore Zen temples and be led in meditation by Zen monks. -

Rail Pass Guide Book(English)

JR KYUSHU RAIL PASS Sanyo-San’in-Northern Kyushu Pass JR KYUSHU TRAINS Details of trains Saga 佐賀県 Fukuoka 福岡県 u Rail Pass Holder B u Rail Pass Holder B Types and Prices Type and Price 7-day Pass: (Purchasing within Japan : ¥25,000) yush enef yush enef ¥23,000 Town of History and Hot Springs! JR K its Hokkaido Town of Gourmet cuisine and JR K its *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. Where is "KYUSHU"? All Kyushu Area Northern Kyushu Area Southern Kyushu Area FUTABA shopping! JR Hakata City Validity Price Validity Price Validity Price International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor 36+3 (Sanjyu-Roku plus San) Purchasing Prerequisite visa may purchase the pass. 3-day Pass ¥ 16,000 3-day Pass ¥ 9,500 3-day Pass ¥ 8,000 5-day Pass Accessible Areas The latest sightseeing train that started up in 2020! ¥ 18,500 JAPAN 5-day Pass *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. This train takes you to 7 prefectures in Kyushu along ute Map Shimonoseki 7-day Pass ¥ 11,000 *Children under the age of 5 are free. However, when using a reserved seat, Ro ¥ 20,000 children under five will require a Children's JR Kyushu Rail Pass or ticket. 5 different routes for each day of the week. hu Wakamatsu us Mojiko y Kyoto Tokyo Hiroshima * All seats are Green Car seats (advance reservation required) K With many benefits at each International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor R Kyushu Purchasing Prerequisite * You can board with the JR Kyushu Rail Pass Gift of tabi socks for customers J ⑩ Kokura Osaka shops of JR Hakata city visa may purchase the pass. -

Explore Shizuoka Explore the Spectacular Natural Environment, Authentic Japanese Culture, Unique History and Renowned Cuisine Of

Explore the spectacular natural environment, authentic Japanese culture, unique history and renowned cuisine of the majestic home of Mount Fuji. Exploreshizuoka.com NATURAL BEAUTY, ON LAND AND SEA From the iconic Mount Fuji in the north to 500km of spectacular Pacific coastline in the south, Shizuoka is a region of outstanding natural beauty, with highlands, rivers and lakes giving way to the white sand beaches and volcanic landscapes of the Izu Peninsula. And all this just one hour from Tokyo by shinkansen (bullet train). Okuoikojo Station MOUNTAINS, FORESTS AND FALLS At 3,776m high, the majestic “Fuji-san” is Japan’s best-known symbol with shrines paying homage to the mountain and paintings illustrating its beauty. Designated a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 2013, the climbing season runs from July to early September. Shizuoka’s central area is dominated by deeply forested mountains that stand over 800 m in height, tea plantations and beautiful waterfalls, such as the Shiraito Falls which, along with the 25m Joren Falls on the Izu Peninsula, is ranked among the 100 most beautiful waterfalls in Japan. The Seven Waterfalls of Kawazu are surrounded by a thick forest of pines, cedars and bamboo with a walking path taking you to all seven in roughly one hour. For a unique and unforgettable experience, visitors can take the historic Oigawa steam railway to visit the beautiful “Dream Suspension Bridge” across the Sumatakyo Gorge. THE IZU PENINSULA Surrounded by ocean on three sides, the Izu Peninsula was designated a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2018. Twenty million years of shifting undersea volcanoes created its dramatic landscapes and natural hot springs. -

KAKEHASHI Project Jewish Americans the 2Nd Slot Program Report

Japan’s Friendship Ties Program (USA) KAKEHASHI Project Jewish Americans the 2nd Slot Program Report 1.Program Overview Under the “KAKEHASHI Project” of Japan’s Friendship Ties Program, 13 Jewish Americans from the United States visited Japan from March 5th to March 12th, 2017 to participate in the program aimed at promoting their understanding of Japan with regard to Japanese politics, economy, society, culture, history, and foreign policy. Through lectures by ministries, observation of historical sites, experiences of traditional culture and other experiences, the participants enjoyed a wide range of opportunities to improve their understanding of Japan and shared their individual interests and experiences through SNS. Based on their findings and learning in Japan, participants made a presentation in the final session and reported on the action plans to be taken after returning to their home country. 【Participating Countries and Number of Participants】 U.S.A. 13 Participants (B’nai B’rith) 【Prefectures Visited】 Tokyo, Hiroshima, Hyogo 2.Program Schedule March 5th (Sun) Arrival at Narita International Airport March 6th (Mon) [Orientation] [Lecture] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, North American Bureau “Japan’s Foreign Policy” [Lecture] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, First Middle East Division, Second Middle East Division “Japan-Middle East Relations” [Courtesy Call] Ambassador Mr. Hideo Sato [Courtesy Call] Mr. Kentaro Sonoura, State Minister for Foreign Affairs [Company Visit] MONEX Inc. March 7th (Tue) Move to Hiroshima by airplane [Historical -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

Hiroshima Hiroshima City Symbol a City of World Significance

Issue No. 46 Spring 2003 DESIGNATED CITY Hiroshima Hiroshima City Symbol A City of World Significance Situated on the Otagawa River Delta and human rights, environmental destruction, and in machinery and metals. Manufacturers facing the Seto Inland Sea, Hiroshima is known other problems that threaten peaceful coexis- account for 13.1% of Hiroshima’s gross munic- as “the City of Water.” Beginning with the con- tence. The mayor of Hiroshima delivers the ipal product, a relatively high figure compared struction of Hiroshima Castle in 1589, the city Peace Declaration at the Peace Memorial to other regional hub cities similar to has flourished as a center of politics, economics, Ceremony on August 6 every year and regularly Hiroshima. and culture for the more than 400 years. issues messages in response to nuclear tests and other related world events. Hiroshima’s knowledge and experience In 1945, the first atomic bombing in history in manufacturing have allowed new industries reduced Hiroshima to rubble. With courage, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are also working to build on existing strengths. HiVEC, the determination and generous support from both to implement Hiroshima-Nagasaki Peace Study Hiroshima Vehicle Engineering Company, is local sources and abroad, Hiroshima has emerged Courses in universities around the world. The a new automotive design firm that will draw as a vibrant city of over 1.13 million that contin- Hiroshima-Nagasaki Courses are designed to on Hiroshima’s wealth of knowledge in the ues to grow and develop into an ideal model for broadly and systematically convey the experi- automobile industry to innovate and invigorate the 21st century.