Cabbage and Onion Maggot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Aspects of the Biology of a Predaceous Anthomyiid Fly, Coenosia Tigrina

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 22 Number 1 - Spring 1989 Number 1 - Spring 1989 Article 2 April 1989 Some Aspects of the Biology of a Predaceous Anthomyiid Fly, Coenosia Tigrina Francis A. Drummond University of Maine Eleanor Groden University of Maine D. L. Haynes Michigan State University Thomas C. Edens Michigan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Drummond, Francis A.; Groden, Eleanor; Haynes, D. L.; and Edens, Thomas C. 1989. "Some Aspects of the Biology of a Predaceous Anthomyiid Fly, Coenosia Tigrina," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 22 (1) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol22/iss1/2 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Drummond et al.: Some Aspects of the Biology of a Predaceous Anthomyiid Fly, <i>Co 1989 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 11 SOME ASPECTS OF THE BIOLOGY OF A PREDACEOUS ANTHOMYIID FLY. COENOSIA TIGRINAI 2 2 3 3 Francis A. Drummond , Eleanor Groden , D.L. Haynes , and Thomas C. Edens ABSTRACT The results of a two-year study in Michigan on the incidence of Coenosia tigrina adults under different onion production practices is presented. In Michigan, C. tigrina has three generations and is more abundant in organic agroecosystems than chemically-intensive onion production systems. Adults of the tiger fly, Coenosia tigrina (F.), are primarily predators of Diptera. -

Onion Maggot, Onion Fly

Pest Profile Photo credit: Left and middle adult, right image pupae. Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License. Common Name: Onion Maggot, Onion Fly Scientific Name: Delia antiqua Order and Family: Diptera: Anthomyiidae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg I.25 mm Eggs are white and elongated. Can be found on the soil near the stem and occasionally on the young leaves and neck of the onion plant. Larva 8-10 mm Larvae are tapered and creamy white in color. Adult 3-6 mm Greyish, looks similar to a housefly, except they have a narrower abdomen, longer legs and overlap their wings when at rest. Pupae 7 mm They are chestnut brown and elongated, found in the soil at a depth of 5-10 cm. Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Chewing (hooked mouthparts) Host plant/s: Serious pest of onion and related Allium crops such as garlic and leeks. Description of Damage (larvae and adults): Only the larva causes damage. Larvae use their hooked mouth parts to enter the base of the plant and then feed on the internal plant tissues. The kind of damage varies depending on time of year and which of three generations is causing the damage. All three generations can be destructive, but the first generation is the most damaging because it can routinely reduce unprotected plant stands by over 50%. First generation: Younger plants are more vulnerable to larval feeding and damage than older plants because as the plants grow the underground portion of the plant and bulb become more difficult for the larvae to penetrate. -

The De Novo Transcriptome and Its Analysis in the Worldwide Vegetable Pest, Delia Antiqua (Diptera: Anthomyiidae)

INVESTIGATION The de novo Transcriptome and Its Analysis in the Worldwide Vegetable Pest, Delia antiqua (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) Yu-Juan Zhang, Youjin Hao, Fengling Si, Shuang Ren, Ganyu Hu, Li Shen, and Bin Chen1 Institute of Entomology and Molecular Biology, College of Life Sciences, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China ABSTRACT The onion maggot Delia antiqua is a major insect pest of cultivated vegetables, especially the KEYWORDS onion, and a good model to investigate the molecular mechanisms of diapause. To better understand the onion maggot biology and diapause mechanism of the insect pest species, D. antiqua, the transcriptome was sequenced high-throughput using Illumina paired-end sequencing technology. Approximately 54 million reads were obtained, trimmed, RNA and assembled into 29,659 unigenes, with an average length of 607 bp and an N50 of 818 bp. Among sequencing these unigenes, 21,605 (72.8%) were annotated in the public databases. All unigenes were then compared de novo against Drosophila melanogaster and Anopheles gambiae. Codon usage bias was analyzed and 332 simple assembly sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected in this organism. These data represent the most comprehensive codon usage bias transcriptomic resource currently available for D. antiqua and will facilitate the study of genetics, genomics, simple sequence diapause, and further pest control of D. antiqua. repeat The onion maggot Delia antiqua is a major insect pest of cultivated in a selected tissue and species of interest and generates quantitative vegetables, especially onions, and is widely distributed in the northern expression scores for each transcript (Wilhelm and Landry 2009). hemisphere. It can be induced into summer and winter diapauses, Such transcriptome analysis will likely replace large-scale microarray both happening at the pupal stage and just after head evagination approaches (Marioni et al. -

Notification of an Emergency Authorisation Issued by Belgium

Notification of an Emergency Authorisation issued by Belgium 1. Member State, and MS notification number BE-Be-2020-02 2. In case of repeated derogation: no. of previous derogation(s) None 3. Names of active substances Tefluthrin - 15.0000 g/kg 4. Trade name of Plant Protection Product Force 1.5 GR 5. Formulation type GR 6. Authorisation holder KDT 7. Time period for authorisation 01/04/2020 - 29/07/2020 8. Further limitations Generated by PPPAMS - Published on 04/02/2020 - Page 1 of 7 9. Value of tMRL if needed, including information on the measures taken in order to confine the commodities resulting from the treated crop to the territory of the notifying MS pending the setting of a tMRL on the EU level. (PRIMO EFSA model to be attached) / 10. Validated analytical method for monitoring of residues in plants and plant products. Source: Reasoned opinion on the setting of maximum residue levels for tefluthrin in various crops1 EFSA Journal 2015;13(7):4196: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4196 1. Method of analysis 1.1.Methods for enforcement of residues in food of plant origin Analytical methods for the determination of tefluthrin residues in plant commodities were assessed in the DAR and during the peer review under Directive 91/414/EEC (Germany, 2006, 2009; EFSA, 2010). The modified multi-residue DFG S 19 analytical method using GC-MSD quantification and its ILV were considered as fully validated for the determination of tefluthrin in high water content- (sugar beet root), high acid content- (orange), high oil content- (oilseed rape) and dry/starch- (maize grain) commodities at an LOQ of 0.01 mg/kg. -

Phytophagous Entomofauna Occurring on Onion Plantations in Poland in Years 1919-2007

2009 vol. 71, 5-14 DOI: 10.2478/v10032-009-0021-z ________________________________________________________________________________________ PHYTOPHAGOUS ENTOMOFAUNA OCCURRING ON ONION PLANTATIONS IN POLAND IN YEARS 1919-2007 Jerzy SZWEJDA, Robert WRZODAK Research Institute of Vegetable Crops Konstytucji 3 Maja 1/3, 96-100 Skierniewice, Poland Received: February 6, 2009; Accepted: September 21, 2009 Summary In years 1919-2007 on domestic onion plantations 37 phytophagous spe- cies taxons belonging to 7 insect orders: Thysanoptera, Homoptera, Heterop- tera, Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera and Orthoptera were noted. Among these groups 22 species were stated as phytophagous, additional taxons were indentified to 5 genus (Thrips, Mamestra, Polia, Agrotis, Agriotes) and 3 fami- lies: fungus gnats (Sciaridae), march flies (Bibionidae), crane flies (Tipulidae). Furthermore 7 species of saprophagous Diptera were collected from damaged onions during harvest. The most common dominant species occurring in all regions of onion production were: onion fly (Delia antiqua Meig.), onion thrips (Thrips tabaci Lind.), onion weevil (Ceutorhynchus suturalis Fabr.), leek moth (Acrolepiospis assectella Zell.) and cutworms (Noctuidae). The population density of: onion beetle (Lilioceris merdigera L.), garlic fly (Suillia lurida Meig.) and leek miner fly (Napomyza gymnostoma Loew) were only a seasonal danger, especially in southern regions of Poland. On wet and rich in organic matter soils some soil dwelling insects such as larvae of Melolontha species (Scarabaeidae), larvae of Agriotes (Elateridae), flies (Diptera) from Tipulidae and Bibionidae families were also occurring periodically. The species and population changes of above mentioned pests allowed to elaborate effective pest control methods of onion plantations. The pest control was performed after field monitoring on the basis of constantly updated short - and long-term forecasting. -

Global Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Molecular Profiles of Summer Diapause Induction Stage of Onion Maggot, Delia Antiqua

INVESTIGATION Global Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Molecular Profiles of Summer Diapause Induction Stage of Onion Maggot, Delia antiqua (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) Shuang Ren,*,† You-Jin Hao,† Bin Chen,† and You-Ping Yin*,1 *Key Lab of Genetic Function and Regulation in Chongqing, School of Life Sciences, Chongqing University, 401331, China and †Institute of Entomology and Molecular Biology, College of Life Sciences, Chongqing Normal University, 401331, China ABSTRACT The onion maggot, Delia antiqua, is a worldwide subterranean pest and can enter diapause KEYWORDS during the summer and winter seasons. The molecular regulation of the ontogenesis transition remains Delia antiqua largely unknown. Here we used high-throughput RNA sequencing to identify candidate genes and process- transcriptome es linked to summer diapause (SD) induction by comparing the transcriptome differences between the most sequencing sensitive larval developmental stage of SD and nondiapause (ND). Nine pairwise comparisons were per- diapause formed, and significantly differentially regulated transcripts were identified. Several functional terms related induction to lipid, carbohydrate, and energy metabolism, environmental adaption, immune response, and aging were genes and enriched during the most sensitive SD induction period. A subset of genes, including circadian clock genes, pathways were expressed differentially under diapause induction conditions, and there was much more variation in circadian clock the most sensitive period of ND- than SD-destined larvae. These expression variations probably resulted in a deep restructuring of metabolic pathways. Potential regulatory elements of SD induction including genes related to lipid, carbohydrate, energy metabolism, and environmental adaption. Collectively, our results suggest the circadian clock is one of the key drivers for integrating environmental signals into the SD induction. -

Onion Maggot

2014 VEGETABLES www.nysipm.cornell.edu/factsheets/vegetables/onion_maggot.pdf Department of Entomology Onion maggot The greyish-brown adult looks almost identical to the Delia antiqua Meigen onion maggot adult, except that it is approximately half to three-quarters its size (~3 mm / ~0.1 in). Seedcorn maggot Erik Smith and Brian Nault may also damage onion seedlings and infest damaged bulbs Department of Entomology, Cornell University, NYSAES, later in the season. Geneva, NY Eggs: Adult onion maggots deposit white elongated Introduction eggs (Fig. 1B) ~I.25 mm in length (~0.05 in) on the soil near the stem and occasionally on the young leaves and neck of Onion maggot, Delia antiqua, is a serious pest of onion the onion plant. and related Allium crops (i.e., garlic and leek) in northern temperate regions throughout the world including North Larvae: Larvae are tapered, creamy-white in color, and America. Although onion maggot will also attack wild relatives reach a length of ~8 mm (~0.3 in) (Fig. 1C). of onion, it is not capable of maintaining high populations Pupae: When fully-grown, the larva leaves the onion on wild hosts. Onion maggot completes three generations plant and enters the soil to pupate at a depth of 5-10 cm. The per year in northern regions. All three generations can be pupa is chestnut brown and ~7 mm long (~0.3 in) (Fig. 1D). destructive, but the first generation is the most damaging because it can routinely reduce plant stands by over 50% if Life cycle crops are not protected1,2. -

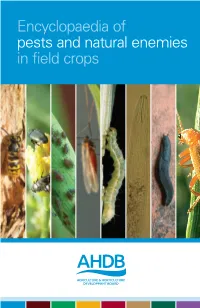

Encyclopaedia of Pests and Natural Enemies in Field Crops Contents Introduction

Encyclopaedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops Contents Introduction Contents Page Integrated pest management Managing pests while encouraging and supporting beneficial insects is an Introduction 2 essential part of an integrated pest management strategy and is a key component of sustainable crop production. Index 3 The number of available insecticides is declining, so it is increasingly important to use them only when absolutely necessary to safeguard their longevity and Identification of larvae 11 minimise the risk of the development of resistance. The Sustainable Use Directive (2009/128/EC) lists a number of provisions aimed at achieving the Pest thresholds: quick reference 12 sustainable use of pesticides, including the promotion of low input regimes, such as integrated pest management. Pests: Effective pest control: Beetles 16 Minimise Maximise the Only use Assess the Bugs and aphids 42 risk by effects of pesticides if risk of cultural natural economically infestation Flies, thrips and sawflies 80 means enemies justified Moths and butterflies 126 This publication Nematodes 150 Building on the success of the Encyclopaedia of arable weeds and the Encyclopaedia of cereal diseases, the three crop divisions (Cereals & Oilseeds, Other pests 162 Potatoes and Horticulture) of the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board have worked together on this new encyclopaedia providing information Natural enemies: on the identification and management of pests and natural enemies. The latest information has been provided by experts from ADAS, Game and Wildlife Introduction 172 Conservation Trust, Warwick Crop Centre, PGRO and BBRO. Beetles 175 Bugs 181 Centipedes 184 Flies 185 Lacewings 191 Sawflies, wasps, ants and bees 192 Spiders and mites 197 1 Encyclopaedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops Encyclopaedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops 2 Index Index A Acrolepiopsis assectella (leek moth) 139 Black bean aphid (Aphis fabae) 45 Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid) 61 Boettgerilla spp. -

(Diptera: Anthomyiidae) in Onion

Bangladesh J. Zool. 47(2): 325-332, 2019 ISSN: 0304-9027 (print) 2408-8455 (online) BIOLOGICAL TRAITS AND SUSCEPTIBILITY OF DELIA ANTIQUA (MEIGEN, 1826) (DIPTERA: ANTHOMYIIDAE) IN ONION Kamrun Nahar, Shanjida Sultana, Tangin Akter and Shefali Begum* Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Abstract: The pre-oviposition period of mated and unmated female reared on Bangladeshi and Indian onion was 4.5 ± 0.5, 4.37 ± 0.6 days and 4.11 ± 0.09, 4.45 ± 0.32 days, respectively. The oviposition period of mated and unmated female was 5.6 ± 0.6, 6.03 ± 0.6 days and 6.48 ± 0.39, 6.5 ± 0.34 days reared on Bangladeshi and Indian onion, respectively. The life cycle of Delia antiqua consisted of four definite stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. The incubation period was1.38 ± 0.11 and 1.25 ± 0.05 days; larval period was 5.7 ± 0.7 and 5.4 ± 0.05 days; pupal period was 6.8 ± 0.2 and 6.08 ± 0.2 days, respectively. There were three larval instars in D. antiqua. To complete the total life cycle it required shorter period in Indian than in Bangladeshi onion. The total life cycle of female was 16.73 ± 0.89 and 15.29 ± 0.45 days, respectively on Bangladeshi and Indian onion. The difference between the life cycle of female was significant (p < 0.05) in Bangladeshi and Indian onion. Fecundity was higher in Indian than in Bangladeshi onion. The fecundity of female D. antiqua reared in Bangladeshi and Indian onion was 75.2 ± 4.09 and 89.2 ± 2.39, respectively and it was significantly (p < 0.05) varied. -

Managing Onion Maggot (Delia Platura)

Managing Onion Maggot (Delia platura) Onion maggot, also known as seed corn maggot, is The maggots have a preference for seeds that are a species of fly belonging to the family Anthomyiidae. damaged, partially decayed or diseased, which in some Several species within this family, including Delia platura, cases means onion maggots are not considered to be a are agricultural pests, and are commonly referred to primary pest. as “root-maggots”. Damage to seeds and seedlings associated with Delia platura has been recorded in a Life Cycle wide range of crops including corn, beans, onions, garlic, There are approximately four generations of onion brassicas, potatoes and spinach. maggots a year, with the life cycle of one generation Originating in Europe, Delia platura has spread to most between 16 – 40 days, depending on temperature. temperate areas of the world, including Australia. It is The white coloured eggs are 1mm long and laid in loose important not to confuse Delia platura with Delia antiqua, clusters on soil that is moist and rich in organic matter. which is also commonly known as onion fly or onion Females lay an average of 250 eggs, which hatch after maggot in other parts of the world. two or three days. The maggots then burrow down looking for food. Larvae are yellowish white and typical maggot shape, they have no legs and a pointed head with black mouth parts. The maggots grow from 0.7mm to 7mm before pupating in the soil. The larval stage lasts for about 20 days and development occurs over a temperature range of 11°C to 33°C. -

EPPO Standards

EPPO Standards GUIDELINES ON GOOD PLANT PROTECTION PRACTICE ALLIUM CROPS PP 2/4(2) English oepp eppo European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization 1, rue Le Nôtre, 75016 Paris, France APPROVAL EPPO Standards are approved by EPPO Council. The date of approval appears in each individual standard. REVIEW EPPO Standards are subject to periodic review and amendment. The next review date for this set of EPPO Standards is decided by the EPPO Working Party on Plant Protection Products. AMENDMENT RECORD Amendments will be issued as necessary, numbered and dated. The dates of amendment appear in each individual standard (as appropriate). DISTRIBUTION EPPO Standards are distributed by the EPPO Secretariat to all EPPO Member Governments. Copies are available to any interested person under particular conditions upon request to the EPPO Secretariat. SCOPE EPPO guidelines on good plant protection practice (GPP) are intended to be used by National Plant Protection Organizations, in their capacity as authorities responsible for regulation of, and advisory services related to, the use of plant protection products. REFERENCES All EPPO guidelines on good plant protection practice refer to the following general guideline: OEPP/EPPO (1994) EPPO Standard PP 2/1(1) Guideline on good plant protection practice: principles of good plant protection practice. Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin 24, 233-240. OUTLINE OF REQUIREMENTS For each major crop of the EPPO region, EPPO guidelines on good plant protection practice (GPP) cover methods for controlling pests (including pathogens and weeds). The main pests of the crop in all parts of the EPPO region are considered. For each, details are given on biology and development, appropriate control strategies are described, and, if relevant, examples of active substances which can be used for chemical control are mentioned. -

An Introduction to the Immature Stages of British Flies

Royal Entomological Society HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS To purchase current handbooks and to download out-of-print parts visit: http://www.royensoc.co.uk/publications/index.htm This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Copyright © Royal Entomological Society 2013 Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects Vol. 10, Part 14 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMATURE STAGES OF BRITISH FLIES DIPTERA LARVAE, WITH NOTES ON EGGS, PUP ARIA AND PUPAE K. G. V. Smith ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON Handbooks for the Vol. 10, Part 14 Identification of British Insects Editors: W. R. Dolling & R. R. Askew AN INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMATURE STAGES OF BRITISH FLIES DIPTERA LARVAE, WITH NOTES ON EGGS, PUPARIA AND PUPAE By K. G. V. SMITH Department of Entomology British Museum (Natural History) London SW7 5BD 1989 ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON The aim of the Handbooks is to provide illustrated identification keys to the insects of Britain, together with concise morphological, biological and distributional information. Each handbook should serve both as an introduction to a particular group of insects and as an identification manual. Details of handbooks currently available can be obtained from Publications Sales, British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD. Cover illustration: egg of Muscidae; larva (lateral) of Lonchaea (Lonchaeidae); floating puparium of Elgiva rufa (Panzer) (Sciomyzidae). To Vera, my wife, with thanks for sharing my interest in insects World List abbreviation: Handbk /dent. Br./nsects. © Royal Entomological Society of London, 1989 First published 1989 by the British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD.