A Complex Ultimate Reality: the Metaphysics of the Four Yogas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 14 Article 10 January 2001 The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West Thomas A. Forsthoefel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Forsthoefel, Thomas A. (2001) "The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 14, Article 10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1253 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Forsthoefel: The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the Westl Professor Thomas A. Forsthoefel Mercyhurst College WILHELM Halbfass's seminal study of appeal among thinkers and spiritUal adepts the concept of experience in Indian religions in the West. Indeed, such 'meeting at the illuminates the philosophical ambiguities of heart' in interfaith dialogue promises the term and its recent appropriations by communion even in the face of unresolved some neo-Advaitins. to serve apologetic theoretical dilemmas. 2 ends. Anantanand Rambachand's own The life and work of Ramana (1879- study of the process of liberation in Advaita 1950), though understudied, are important Vedanta also critically reviews these for a number of reasons, not the least of apologetic strategies, arguing that in which is the fact that together they represent privileging anubhava, they undervalue or a version of Advaita abstracted from misrepresent the im;ortance given to sruti in traditional monastic structures, thus Sankara's Advaita. -

Comment Fundamentalism and Science

SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Journal of Science Communication ISSN 1824 – 2049 http://jcom.sissa.it/ Comment Fundamentalism and science Massimo Pigliucci The many facets of fundamentalism. There has been much talk about fundamentalism of late. While most people's thought on the topic go to the 9/11 attacks against the United States, or to the ongoing war in Iraq, fundamentalism is affecting science and its relationship to society in a way that may have dire long-term consequences. Of course, religious fundamentalism has always had a history of antagonism with science, and – before the birth of modern science – with philosophy, the age-old vehicle of the human attempt to exercise critical thinking and rationality to solve problems and pursue knowledge. “Fundamentalism” is defined by the Oxford Dictionary of the Social Sciences 1 as “A movement that asserts the primacy of religious values in social and political life and calls for a return to a 'fundamental' or pure form of religion.” In its broadest sense, however, fundamentalism is a form of ideological intransigence which is not limited to religion, but includes political positions as well (for example, in the case of some extreme forms of “environmentalism”). In the United States, the main version of the modern conflict between science and religious fundamentalism is epitomized by the infamous Scopes trial that occurred in 1925 in Tennessee, when the teaching of evolution was challenged for the first time 2,3. That battle is still being fought, for example in Dover, Pennsylvania, where at the time of this writing a court of law is considering the legitimacy of teaching “intelligent design” (a form of creationism) in public schools. -

Recent Biographies of Ramakrishna – a Study

RECENT BIOGRAPHIES OF RAMAKRISHNA – A STUDY RUCHIRA MITRA Research Scholar, PP ENG 0054 Rayalaseema University, Andhra Pradesh (INDIA) [Ex HOD, English, Shadan Degree College for Boys, Hyderabad Ex Lecturer, Post Graduate College, OU, Secunderabad] (AP), INDIA. The spiritual giants are the most tangible form of divinity through which people find solace in difficult times. Their biographies perpetuate their memory as well as promote devoutness and spirituality. Biography of saints is again becoming popular nowadays. It also throws light on the problems in writing a biography of a saint because most of the drama of a saint’s life is lived within; and charting the inner dimensions of a saint has always been a challenging task. Such studies are often inspired by veneration instead of deep understanding. On the other hand, there may be a biography written by a detractor in which sublime ideals and transcendental thoughts are trivialized. This becomes evident if we do critical appreciation of some famous biographies. Ramakrishna, who, more than a century after his death continues to dominate secular Hindu consciousness, was a key figure in what is considered to be the Hindu Renaissance of the 19th century. His biographies will be used to show the wide range of perspectives - from abjectly critical to totally objective to rank idolatry - – taken up by the authors. A big problem in interpreting a person’s character arises when the biographer belongs to a different culture. Two foreign interpreters of Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita Malcolm McLean and Jeffrey Kripal fall under this category. In Kali’s Child Kripal takes to the hermeneutic of suspicion as he claims to reveal the secret that has been hidden for over a century: that Ramakrishna was a conflicted, unwilling homoerotic Tantric. -

Idealism and Realism in Western and Indian Philosophies

IDEALISM AND REALISM IN WESTERN AND INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES —Dr. Sohan Raj Tater Over the centuries the philosophical attitude in the west has never been constant but undulated between Idealism and Realism. The difference between these two appears to be irreconcilable, being more or less bound up with the innate difference of predispositions and tendencies varying from person to person. The result is an uncompromising antagonism. The western scholars, who were brought up in the tradition of Kant and Hegel, and who studied Indian philosophies, were more sympathetic towards the Idealistic systems of India. In the 19 th century, there was a predominant wave of monism and scholars like Max Muller were naturally attracted towards the metaphysical views of Sankara etc. and the uncompromising Monism of Vedanta was much admired as the cream of the oriental wisdom. There have been different Idealistic views in Western and Indian philosophies as follows : Western Idealism (i) Platonic Idealism The Idealism of Plato is objective in the sense that the ideas enjoy an existence in a real world independent of any mind. Mind is not antecedent for the existence of ideas. The ideas are there whether a mind reveals them or not. The determination of the phenomenal world depends on them. They somehow determine the empirical existence of the world. Hence, Plato’s conception of reality is nothing but a system of eternal, immutable and immaterial ideas. (ii) Idealism of Berkeley Berkeley may be said to be the founder of Idealism in the modern period, although his arrow could not touch the point of destination. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

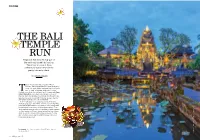

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

The Main Schools of Economic Thought

THE MAIN SCHOOLS OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT Level Initiation 5 Modules EDUCATION GOALS Understand the different schools of economic thought Recognise the key authors of the different schools of economic thought Be able to link the various theories to the school of thought that 3 H developed them Understand the contributions and the limitations of the different schools of economic thought WORD FROM THE AUTHOR « Economic reflections have existed since antiquity, emerging initially in Ancient Greece and then in Ancient China, where market production and an economy first appear to have been developed. Since 1800, different schools of economic thought have succeeded one another: the foundations of economic science first emerged via the two “precursors” of classical economic thought: the schools of mercantilism and physiocracy; the first half of the 19th century saw the birth of the classical school; while The Marxian school emerged during the second half of the 19th century; the neoclassical school is considered to be the fourth main school of economic thought. Finally, the last school of economic thought is the Keynesian school. In this course I invite you to examine these five schools of thought in detail: What are their theories? Who were the key authors of these schools? » ACTION ON LINE / Le Contemporain - 52 Chemin de la Bruyère - 69574 LYON DARDILLY CEDEX Tél : +33 (0) 4 37 64 40 10 / Mail : [email protected] / www.actiononline.fr © All rights reserved MODULES M181 – THE PRECURSORS Objectives education Understand mercantilism and its main authors Understand physiocracy and its main authors Word from the author « The mercantilist and physiocratic schools are often referred to as the precursors of classical economic thought. -

Professors of Paranoia?

http://chronicle.com/free/v52/i42/42a01001.htm From the issue dated June 23, 2006 Professors of Paranoia? Academics give a scholarly stamp to 9/11 conspiracy theories By JOHN GRAVOIS Chicago Nearly five years have gone by since it happened. The trial of Zacarias Moussaoui is over. Construction of the Freedom Tower just began. Oliver Stone's movie about the attacks is due out in theaters soon. And colleges are offering degrees in homeland-security management. The post-9/11 era is barreling along. And yet a whole subculture is still stuck at that first morning. They are playing and replaying the footage of the disaster, looking for clues that it was an "inside job." They feel sure the post-9/11 era is built on a lie. In recent months, interest in September 11-conspiracy theories has surged. Since January, traffic to the major conspiracy Web sites has increased steadily. The number of blogs that mention "9/11" and "conspiracy" each day has climbed from a handful to over a hundred. Why now? Oddly enough, the answer lies with a soft-spoken physicist from Brigham Young University named Steven E. Jones, a devout Mormon and, until recently, a faithful supporter of George W. Bush. Last November Mr. Jones posted a paper online advancing the hypothesis that the airplanes Americans saw crashing into the twin towers were not sufficient to cause their collapse, and that the towers had to have been brought down in a controlled demolition. Now he is the best hope of a movement that seeks to convince the rest of America that elements of the government are guilty of mass murder on their own soil. -

Meningkatkan Mutu Umat Melalui Pemahaman Yang Benar Terhadap Simbol Acintya (Perspektif Siwa Siddhanta)

MENINGKATKAN MUTU UMAT MELALUI PEMAHAMAN YANG BENAR TERHADAP SIMBOL ACINTYA (PERSPEKTIF SIWA SIDDHANTA) Oleh: I Gusti Made Widya Sena Dosen Fakultas Brahma Widya IHDN Denpasar Abstract God will be very difficult if understood with eye, to the knowledge of God through nature, private and personification through the use of various symbols God can help humans understand God's infinite towards the unification of these two elements, namely the unification of physical and spiritual. Acintya as a symbol or a manifestation of God 's Omnipotence itself . That what really " can not imagine it turns out " could imagine " through media portrayals , relief or statue. All these symbols are manifested Acintya it by taking the form of the dance of Shiva Nataraja, namely as a depiction of God's omnipotence , to bring in the actual symbol " unthinkable " that have a meaning that people are in a situation where emotions religinya very close with God. Keywords: Theology, Acintya, Siwa Siddhanta & Siwa Nataraja I. PENDAHULUAN Kehidupan sebagai manusia merupakan hidup yang paling sempurna dibandingkan dengan makhluk ciptaan Tuhan lainnya, hal ini dikarenakan selain memiliki tubuh jasmani, manusia juga memiliki unsur rohani. Kedua unsur ini tidak dapat dipisahkan dan saling melengkapi diantara satu dengan lainnya. Layaknya garam di lautan, tidak dapat dilihat secara langsung tapi terasa asin ketika dikecap. Jasmani manusia difungsikan ketika melakukan berbagai macam aktivitas di dunia, baik dalam memenuhi kebutuhan hidup (kebutuhan pangan, sandang dan papan), reproduksi, bersosialisasi dengan makhluk lainnya, dan berbagai aktivitas lainnya, sedangkan tubuh rohani difungsikan dalam merasakan, memahami dan membangun hubungan dengan Sang Pencipta, sehingga ketenangan, keindahan dan kebijaksanaan lahir ketika penyatuan diantara kedua unsur ini berjalan selaras, serasi dan seimbang. -

Rethinking Advaita: Who Is Eligible to Read Advaita Texts? Anantanand Rambachan

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 22 Article 6 2009 Rethinking Advaita: Who is Eligible to Read Advaita Texts? Anantanand Rambachan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Recommended Citation Rambachan, Anantanand (2009) "Rethinking Advaita: Who is Eligible to Read Advaita Texts?," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 22, Article 6. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1433 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Rambachan: Rethinking Advaita: Who is Eligible to Read Advaita Texts? Rethinking Advaita: Who is Eligible to Read Advaita Texts?1 _Anantanand Rambachan St. Olaf College MY most recent work, The Advaita Worldview: presents us with a number of significant God, World and Humanity, exemplifies two questions centered on eligibility to read Advaita related movements. 2 First, I join the growing texts, the insider-outsider dilemma, and the stream of scholars who are making efforts to Christian theologian as reader of Advaita. Am I distinguish the interpretations of Sankara from as an Advaitin committed to an important stream later Advaita exegetes. The uncritical equation of the Hindu tradition, authorized to speak for of Sankara's views with those of later exegetes and about the tradition in ways that Thatamanil needs to be challenged.3 Second, I contend that cannot? Who are the new conversation partners Advaita reflection and scholarship cannot limit for Advaita? I want to focus my response on itself to the clarification of Sankara's some of these questions through an examination interpretations. -

Original Monotheism: a Signal of Transcendence Challenging

Liberty University Original Monotheism: A Signal of Transcendence Challenging Naturalism and New Ageism A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries by Daniel R. Cote Lynchburg, Virginia April 5, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Cote All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet Dr. T. Michael Christ Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity Dr. Phil Gifford Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Daniel R. Cote Liberty University School of Divinity, 2020 Mentor: Dr. T. Michael Christ Where once in America, belief in Christian theism was shared by a large majority of the population, over the last 70 years belief in Christian theism has significantly eroded. From 1948 to 2018, the percent of Americans identifying as Catholic or Christians dropped from 91 percent to 67 percent, with virtually all the drop coming from protestant denominations.1 Naturalism and new ageism increasingly provide alternative means for understanding existential reality without the moral imperatives and the belief in the divine associated with Christian theism. The ironic aspect of the shifting of worldviews underway in western culture is that it continues with little regard for strong evidence for the truth of Christian theism emerging from historical, cultural, and scientific research. One reality long overlooked in this regard is the research of Wilhelm Schmidt and others, which indicates that the earliest religion of humanity is monotheism. Original monotheism is a strong indicator of the existence of a transcendent God who revealed Himself as portrayed in Genesis 1-11, thus affirming the truth of essential elements of Christian theism and the falsity of naturalism and new ageism. -

Is Ultimate Reality Unlimited Love?

Chapter 1: Stephen Post Sir John’s Biggest Question: An Introduction Sir John wrote me these words in a letter dated August 3, 2001, words that I know he thought deeply about and felt to be crucial for spiritual progress: I am pleased indeed, by your extensive plans for research on human love. I will be especially pleased if you find ways to devote a major part, perhaps as much as one third of the grant from the Templeton Foundation, toward research evidences for love over a million times larger than human love. To clarify why I expect vast benefits for research in love, which does not originate entirely with humans, I will airmail to you in the next few days some quotations from articles I have written on the subject. Is it pitifully self-centered to assume, if unconsciously, that all love originates with humans who are one temporary species on a single planet? Are humans created by love rather than humans creating love? Are humans yet able to perceive only a small fraction of unlimited love, and thereby serve as agents for the growth of unlimited love? As you have quoted in your memorandum, it is stated in John 1 that “God is love and he who dwells in love dwells in God and God in him.” For example, humans produce a very mysterious force called gravity but the amount produced by humans is infinitesimal compared to gravity from all sources. Can evidences be found that the force of love is vastly larger than humanity? Can methods or instruments be invented to help humans perceive larger love, somewhat as invention of new forms of telescopes helps human perceptions of the cosmos? What caused atoms to form molecules? What caused molecules to form cells temporality? Could love be older than the Big Bang? After the Big Bang, was gravity the only force to produce galaxies and the complexity of life on planets? Sir John wanted to devote at least one third of his grant to support investigations into a love “over a million times larger than human love.” Anything less would be an act of human arrogance.