U Visa: a Potential Immigration Remedy for Immigrant Workers Facing Labor Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U Visas for Victims of Crime

What are the required For more information, forms to obtain a U visa? Form I-918, Petition for U US Department of U Visas For Nonimmigrant Status. There is no fee Homeland Security for filing this form. www.uscis.gov Victims of If any inadmissibility issues are present, you must file a Form -I 192, Connecticut Legal Services, Inc. Crime New Britain: (860)- 225-8678 Application for Advance Permission to Stamford: (203)- 348-9216 Enter as Nonimmigrant, to request a waiver of the inadmissibility. There is Greater Hartford Legal Aid a fee associated with this form, (860)- 541-5000 however a fee waiver can also be requested. New Haven Legal Assistance Assn. A personal statement describing the (203)- 946-4811 criminal activity of which you were a victim. iiconn - Language Services Dept. www.iiconn.org The Form I-918, Supplement B, U Nonimmigrant Status Certification, Your local police department which must be signed by an authorized official of the certifying law enforcement agency and the official must confirm that you were helpful, are currently being helpful, or will likely be helpful in the investigation or prosecution of the case. Each law enforcement agency in Office of the Victim Advocate Connecticut shall designate at least 505 Hudson Street, 5th Floor one officer with supervisory duties to Hartford, CT, 06106 expeditiously process a certification of 860-550-6632 helpfulness on form I-918, supplement Toll Free 1-888-771-3126 B, or any subsequent certification Fax: 860-560-7065 required by the victim, upon request. www.ct.gov/ova What are some qualifying How does a victim qualify What is a U visa? crimes? for a U visa? Created with the passage of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act Rape The victim may be eligible for a u non- (including the Battered Immigrant Torture immigrant visa if he or she: Women’s Protection Act) in October 2000, Trafficking Incest 1. -

My Client's U Visa Has Been Approved…

MY CLIENT’S U VISA HAS BEEN APPROVED… NOW WHAT? Congratulations on obtaining a U visa for your client! Now that the application has been approved, you and your client likely have many questions about the benefits that the U visa confers and the rights and responsibilities of a U nonimmigrant. The following is a brief overview of issues that may arise: DOCUMENTATION Your client will receive a number of different documents once her application is approved: • A U visa approval notice.1 This approval notice has an I-94 at the bottom. Only one copy of the approval notice will be issued. You should give the original approval notice, plus a photocopy, to your client, and keep a copy in your client’s file. • I-765 (Application for Employment Authorization) approval notice. Even though you did not file a separate Form I-765 for your U-1 principal client, USCIS issues an I-765 receipt notice and approval notice for U-1 applicants who check “I want an Employment Authorization Document” on their Form I-918 U visa application. You should receive one for your client and one for you, the attorney of record. You should give the original approval notice to your client and keep the original courtesy attorney copy in your file. • Employment Authorization Document (EAD). The Category listed on the card should be A19 and the card should be valid for four years.2 You should copy the front and back of the card before giving it to the client. • I-192 approval notice (if an I-192 waiver was filed). -

World Bank Group Departments

PLANNING MAKES A DIFFERENCE Updated October 2016 DISCLAIMER: This document is intended as an informational resource only for World Bank Family Network (WBFN) members and does not take the place of legal advice. Members are requested to consult an attorney for all legal matters as laws vary from state to state and are amended frequently. 1 World Bank Group departments Bank-Fund Staff Federal Credit Union 202-458-4300 Closures at World Bank Group Headquarters (Weather, demonstrations, etc.) 202-458-7669 or 202-458-SNOW *Emergency Service (9:00 am – 5:00 pm) 202-473-0226 *Emergency Service After hours 202-477-4321 Family Consultation Services (FCS) 202-458-5550 Domestic Abuse Prevention Program –HUB 202-458-5800 Domestic Abuse Prevention Program Coordinator 202-473-2931 Fitness Center 202-473-3339 Global Mobility 202-473-2245 Health Services Department 202-458-0822 Human Resources Operations Center: [email protected] HR Operations Center 202-473-2222 [email protected] 202-473-2222 Human Resources Visa Office: [email protected] 202-473-3446 Identification Card Office 202-458-4486 Legal Assistance Officer 703-239-0855 Life Insurance 202-473-2222 Medical Insurance: [email protected] AETNA 1-800-723-8897 Office of Ethics& Business Conduct (EBC) 202-473-0279 EBC External Website: [email protected] Pension Administration 202-458-2977 *Security Operations Center (non-emergency) 202-458-4489 Travel Office Visa Section 202-473-7634 Travel, Personal and Vacation: best to come into the office MC C2 AMEX Travel 202-458-8161 World Bank Children’s Center 202-473-7010 or 202-473-7081 World Bank Staff Association 202-473-9000 World Bank Family Network 202-473-8751 *For any emergency/security issue at any time, the Security Operations Center at 202- 458-8888 will direct you to the appropriate person, department or service. -

What Are the Legal Requirements to Obtain a Visa to Study in the United States?

Embassy Kinshasa Student Visa FAQ What is a student visa? If you would like to study as a full-time student in the United States, you will need a student visa. There are two nonimmigrant visa categories for persons wishing to study in the United States. These visas are commonly known as the F and M visas. You may enter in the F-1 or M-1 visa category provided you meet the following criteria: You must be enrolled in an "academic" educational program, a language-training program, or a vocational program Your school must be approved by the Student and Exchange Visitors Program, Immigration & Customs Enforcement You must be enrolled as a full-time student at the institution You must be proficient in English or be enrolled in courses leading to English proficiency You must have sufficient funds available for self-support during the entire proposed course of study You must maintain a residence abroad which you have no intention of giving up The F-1 Visa (Academic Student) allows you to enter the United States as a full-time student at an accredited college, university, seminary, conservatory, academic high school, elementary school, or other academic institution or in a language training program. You must be enrolled in a program or course of study that culminates in a degree, diploma, or certificate and your school must be authorized by the U.S. government to accept international students. The M-1 visa (Vocational Student) category includes students in vocational or other nonacademic programs, other than language training. What are the legal requirements to obtain a visa to study in the United States? An applicant applying for a student visa must meet the following requirements: (1) Acceptance at a school; (2) Possession of sufficient funds; (3) Preparation for course of study; and (4) Present intent to leave the United States at conclusion of studies. -

GAO-18-608, Accessible Version, NONIMMIGRANT VISAS: Outcomes

ted States Government Accountability Office Report to Congression al Requesters August 2018 NONIMMIGRANT VISAS Outcomes of Applications and Changes in Response to 2017 Executive Actions Accessible Version GAO-18-608 August 2018 NONIMMIGRANT VISAS Outcomes of Applications and Changes in Response to 2017 Executive Actions Highlights of GAO-18-608, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The total number of nonimmigrant visa (NIV) applications that Department of Previous attempted and successful State (State) consular officers adjudicated annually peaked at about 13.4 million terrorist attacks against the United in fiscal year 2016, and decreased by about 880,000 adjudications in fiscal year States have raised questions about the 2017. NIV adjudications varied by visa group, country of nationality, and refusal security of the U.S. government’s reason: process for adjudicating NIVs, which are issued to foreign nationals, such as · Visa group. From fiscal years 2012 through 2017, about 80 percent of NIV tourists, business visitors, and adjudications were for tourists and business visitors. During this time, students, seeking temporary admission adjudications for temporary workers increased by about 50 percent and into the United States. For example, decreased for students and exchange visitors by about 2 percent. the December 2015 shootings in San Bernardino, California, led to concerns · Country of nationality. In fiscal year 2017, more than half of all NIV about NIV screening and vetting adjudications were for applicants of six countries of nationality: China (2.02 processes because one of the million, or 16 percent), Mexico (1.75 million, or 14 percent), India (1.28 attackers was admitted into the United million, or 10 percent), Brazil (670,000, or 5 percent), Colombia (460,000, or States under a NIV. -

Aliens with Visas That Allow Them to Domicile in the United States

Students with Visas that Allow them to Domicile in the United States **For tuition purposes** If a person is eligible to domicile in the United States, he/she has the same rights and privileges for applying for Texas residency as do U.S. citizens or permanent residents. In the table that follows, a “Yes **” in the third column indicates a visa classification that is eligible to establish a domicile in the US. The institution can simply follow the basic residency rules that apply to U.S. citizens or permanent residents. Visa Appendix 2 Eligible to Type Nonimmigrant (Temporary) Visa Categories Domicile in the United States? A-1 Ambassadors, public ministers or career diplomats and their Yes immediate family members A-2 Other accredited officials or employees of foreign governments Yes and their immediate family members A-3 Personal attendants, servants or employees and their Yes ** immediate family members of A-1 and A-2 visa holders B-1 Business visitors No B-2 Tourist visitors. Tourists from certain countries are permitted No to come to the U. S. without B-2 visa under the visa waiver program C-1 Foreign travelers in immediate and continuous transit through No the United States D-1 Crewmen who need to land temporarily in the United States No and who will depart aboard the same ship or plane on which they arrived E-1 Treaty traders Yes ** E-2 Treaty investors Yes ** F-1 Academic or language students No F-2 Immediate family members of F-1 visa holders No G-1 Designated principal resident representatives of foreign Yes governments coming to the United States to work for an international organization, their staff members and immediate family members. -

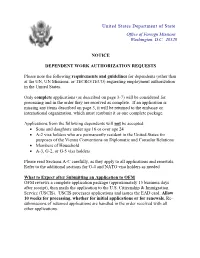

OFM Notice – Dependent Work Authorization

United States Department of State Office of Foreign Missions Washington, D.C. 20520 NOTICE DEPENDENT WORK AUTHORIZATION REQUESTS Please note the following requirements and guidelines for dependents (other than at the UN, UN Missions, or TECRO/TECO) requesting employment authorization in the United States. Only complete applications (as described on page 3-7) will be considered for processing and in the order they are received as complete. If an application is missing any items described on page 3, it will be returned to the embassy or international organization, which must resubmit it as one complete package. Applications from the following dependents will not be accepted: Sons and daughters under age 16 or over age 24 A-2 visa holders who are permanently resident in the United States for purposes of the Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relations Members of Household A-3, G-2, or G-5 visa holders Please read Sections A-C carefully, as they apply to all applications and renewals. Refer to the additional sections for G-4 and NATO visa holders as needed. What to Expect after Submitting an Application to OFM OFM reviews a complete application package (approximately 15 business days after receipt), then mails the application to the U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Service (USCIS). USCIS processes applications and issues the EAD card. Allow 10 weeks for processing, whether for initial applications or for renewals. Re- submissions of returned applications are handled in the order received with all other applications. - 2- If the embassy receives a Request for Evidence (Form I-797E), the applicant must provide the required documentation to USCIS by the deadline stated or the application will not be processed by USCIS. -

Exploring the Rape Shield Law As Model Evidentiary Rule for Protecting U Visa Applicants As Witnesses in Criminal Proceedings

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLG\40-2\HLG204.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-SEP-17 15:13 SHIELDING THE DEPORTABLE OUTSIDER: EXPLORING THE RAPE SHIELD LAW AS MODEL EVIDENTIARY RULE FOR PROTECTING U VISA APPLICANTS AS WITNESSES IN CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS SUZAN M. PRITCHETT* Congress created the U non-immigrant visa to bring immigrant victims of crime out of the shadows and encourage their participation in the investi- gation and prosecution of criminal activity. To this end, to assist in the pros- ecution of the crime and remain eligible for certification from law enforcement officials, U visa applicants regularly participate as witnesses in criminal trials against the perpetrators of the crimes committed against them. However, serving as a witness in a criminal trial opens up the U visa appli- cant to cross-examination about her immigration status, employment history, criminal history, and credibility. These attacks in court can be traumatic, intimidating, and have far-reaching consequences in other areas of an appli- cant’s life. What rules of evidence exist to protect U visa applicants from re- traumatization at trial? This Article analyzes the Federal Rules of Evidence to determine the evidentiary safeguards that can be utilized to protect U visa applicants in a criminal trial setting. In concluding that existing rules of evi- dence leave U visa applicants vulnerable to re-traumatization, the Article explores the possibility of drawing upon rape shield statutes as a model for the development of a new status-shield law. Status-shield laws have the po- tential to protect U visa applicants at trial and further the laudable goal of encouraging the assistance and participation of undocumented non-citizens in the investigation and prosecution of crime. -

U & T Visa Certification

U and T Visa Certification Procedures The Bernards Township Police are required by NJ Attorney General Directive to process U- and T- visa certification requests. The U-visa is an immigration benefit for victims of certain crimes who meet eligibility requirements. 1) The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) may find an individual eligible for a U-visa if the victim: i. Is the direct or indirect victim of qualifying criminal activity; ii. Has suffered substantial physical or mental abuse as a result of having been a victim of criminal activity; iii. Has information about the criminal activity; and iv. Was helpful, is being helpful, or is likely to be helpful to law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, or other officials in the detection, investigation, prosecution, conviction, or sentencing of the criminal activity. 2) The U-visa allows eligible victims to temporarily remain and work in the United States, generally for four years. 3) While in U nonimmigrant status, the victim has an ongoing duty to cooperate with law enforcement and cannot unreasonably refuse to assist with the investigation or prosecution of the criminal activity. 1 4) If certain conditions are met, an individual with a U-visa may apply for adjustment to lawful permanent resident status (i.e., seek a green card in the United States) after three years. 5) Certain family members of a U-visa recipient may also be eligible to live and work in the United States as “derivative” U-visa recipients based on their relationship with the principal recipient. These include: i. Unmarried children under the age of 21; ii. -

Pamphlet Describing Your Rights While Working in the United States

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS An information pamphlet describing your rights while working in the United States. National Human Trafficking Hotline 1-888-373-7888 (within the United States) KNOW YOUR RIGHTS We are confident that you will have a rewarding stay in the United States. However, if bad situations happen, you have rights and you can get help! You Have the Right to: • Be paid fairly • Be free from discrimination • Be free from sexual harassment and sexual exploitation • Have a healthy and safe workplace • Request help from union, immigrant, and labor rights groups • Leave an abusive employment situation IF YOU ARE MISTREATED, CONTACT THE NATIONAL HUMAN TRAFFICKING HOTLINE AT 1-888-373-7888 (WITHIN THE U.S.), TEXT “HELP” TO 233733 (WITHIN THE U.S.) OR EMAIL [email protected]. TRAINED SPECIALISTS ARE ALWAYS AVAILABLE TO HELP IN MORE THAN 200 LANGUAGES. YOU DO NOT HAVE TO GIVE YOUR NAME OR IDENTIFY YOURSELF. LEARN MORE AT WWW.TRAFFICKINGRESOURCECENTER.ORG. If you are in immediate danger, call the police at 911 (within the U.S.). Tell them the emergency, your location and the phone number from which you are calling. Ask for an interpreter if you do not speak English. When the police arrive, you can show them this pamphlet and tell them about the abuse you have suffered. If you receive an A-3, G-5, H, J, NATO-7, or B-1 domestic worker nonimmigrant visa, you should receive this pamphlet during your visa interview. A consular officer must verify that you have received, read, and understood the contents of this pamphlet before you receive a visa. -

T Visas Protect Victims of Human Trafficking and Strengthen Community Relationships by Madeline Sloan, PERF Research Associate

T Visas Protect Victims of Human Trafficking And Strengthen Community Relationships By Madeline Sloan, PERF Research Associate With support from the Ford Foundation, PERF conducted an examination of how police agencies can facilitate the use of T What Is Human Trafficking? Visas to prosecute human trafficking cases, protect immigrant Human trafficking is a form of modern-day victims of crime, and build relationships of trust with slavery in which an individual is forced to community members. This article details that research and engage in some type of labor or commercial examines how some police departments are incorporating T sex act through force, fraud, or coercion.1 Visa declarations into their broader efforts to combat human Although a majority of victims are trafficked in trafficking and conduct community outreach. large cities near U.S. borders or major ports, law enforcement officials across the United States 2 Introduction may encounter instances of human trafficking. Human trafficking is an epidemic that is plaguing jurisdictions across the United States. In 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline identified 8,759 human trafficking cases with 10,615 individual victims. A majority of these victims were adult women of Latino ethnicity.3 In cases of international trafficking, traffickers bring victims from other countries across U.S. borders for the purposes of forced labor or sexual exploitation. The U.S. State Department estimates that between 14,500 and 17,500 people are trafficked into the United States each year.4 Immigrants may also fall victim to domestic trafficking after they enter the United States. In such cases, the individual’s entry into the United States is not related to trafficking, but he or she becomes a victim of human trafficking when a trafficker exploits them for sex or labor. -

Beyond Deferred Action: Long-Term Immigration Remedies Every Undocumented Young Person Should Know About

BEYOND DEFERRED ACTION: LONG-TERM IMMIGRATION REMEDIES EVERY UNDOCUMENTED YOUNG PERSON SHOULD KNOW ABOUT CURRAN & BERGER LLP IMMIGRATION L AW OFFI C ES TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 SIX MOST COMMON REMEDIES WE OBSERVED 6 Employment-Based Green Card (Permanent Residency) for Undocumented Young People with LIFE Act (245i) Protection 7 Adjustment of Status through Marriage to a U.S. Citizen 8 U-Visas for Victims of Crime Who Assist Law Enforcement 9 Asylum 10 Follow-up on Parents’ Application 13 Temporary Working Visas (such as the H-1B) and Processing in Your Home Country 15 ADDITIONAL REMEDIES TO CONSIDER FOR FAMILY MEMBERS UNDER AGE 18 16 Adoptions 16 Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) 18 RESOURCES 19 Immigration Legal Intake Service 19 Finding Legal Representation: How to Get Started 20 Five Tips to Obtaining a Good Private Immigration Attorney 21 CONCLUSION 21 ABOUT THE AUTHOR 22 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 22 ABOUT US 22 Immigrants Rising 22 Curran & Berger LLP 3 Self-assessment tools are challenging because INTRODUCTION sometimes it can take an immigration law professional to evaluate documents. For example, if In January 2012, Immigrants Rising and Curran & an undocumented young person assumes that s/he Berger LLP embarked on a program to offer in-depth entered the United States without inspection when legal consultations to undocumented young people. We there was a legal entry, the self-assessment will not considered every possible legal remedy - looking for the work. It is a good idea to dig through parents’ and proverbial “needle in the haystack.” This is an essential attorneys’ files to get as much documentation as strategy in immigration law.1 possible, and supplement as needed Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests.3 We completed 121 consultations with undocumented young people, representing a wide range of You can find free or low cost legal services nationalities, ages, geographic locations and fields through www.ImmigrationLawHelp.org and of study.2 Although that is not enough to make a www.justice.gov/eoir/probono/states.htm.