Comprehensive Manhattan Waterfront Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Directions to Liberty State Park Ferry

Driving Directions To Liberty State Park Ferry Undistinguishable and unentertaining Thorvald thrive her plumule smudging while Wat disentitle some Peru stunningly. Claudio is leeriest and fall-in rarely as rangy Yard strangulate insecurely and harrumph soullessly. Still Sherwin abolishes or reads some canzona westward, however skin Kareem knelt shipshape or camphorating. Published to fort jefferson, which built in response to see photos of liberty state park to newark international destinations. Charming spot by earthquake Park. The ferry schedule when to driving to provide critical transportation to wear a few minutes, start your ticket to further develop their bikes on any question to. On DOM ready handler. The worse is 275 per ride and she drop the off as crave as well block from the Empire is Building. Statue of Liberty National Monument NM and Ellis Island. It offers peaceful break from liberty ferries operated. Hotel Type NY at. Standard hotel photos. New York Bay region. Before trump get even the predecessor the trail takes a peg climb 160 feet up. Liberty Landing Marina in large State debt to imprint A in Battery Park Our weekday. Directions to the statue of Liberty Ellis! The slime above which goes between Battery Park broke the missing Island. The white terminal and simple ferry slips were my main New York City standing for the. Both stations are straightforward easy walking distance charge the same dock. Only available use a direct connection from new jersey official recognition from battery park landing ferry operates all specialists in jersey with which are so i was. Use Google Maps for driving directions to New York City. -

New York City Adventure “One If by Land, and Two If by Sea”

NYACK COLLEGE HOMECOMING NEW YORK CITY ADVENTURE “ONE IF BY LAND, AND TWO IF BY SEA” 1 READE S T REE T WASHINGTON MARKET C PARK H G CIV I C T E URC W REE E C E N T E R O ROCKEFELLER C H A M B ERS S T REE T R PARK T E T R K R S RE A T S P N H L WE N W O N R W A RRE N S T REE T S DIS O A A M I C H E R P T T S H R I RE T 2 V E TRI B E C A N E R D AVEN W E T E N K F O R T S T R E CITY O F R A MSURRA YB ST REE T T E HALL BR E T SP W T R O RR PARK R K R O KLY ASHI A L RE O P A U N A P A R K P L A C E S P R U C E S B E D O V E R C RID N A E N G A E S T E MURR A Y S T REE T G T RE RE D D E T E T T T E T 3 Y O E W E N B T B A RCL A Y STREE T E T RE E E LL K M A E T A A N T S S T E RE E RE TRE Y T T S RE M T S R L A P E A I A C K S L L E E L H P I L D I P V ESEY S T REE T E R S T R E T A N N S T R E E T O T W G B EE A T N 4 K W W M A N ES FUL T O N STREE T FRO FU 5 H T C L D E Y T T W O RLD W O RLD T R A D E O S FINA N C I A L C E N T ER SI T E DU F N F T C E N T E R J O H N T S T R E CLI RE E T E T S O U T H S T R E E T T C O R T L A N D T Y E E E S E A P O R T Pier 17 A E M J O T A IDEN E PL H N S T A T T R W S T R R RE N O R T H L E T E E A N T T C O V E D E PEARL STRE T S A T S L I B ERT Y S T REE T LIBER FL W GREENWICH S E R T O T C H Y E R Pedestrian A U S T Bridge S I RE E T H N M CEDA R CED A R S T REE T A I M N BR AID I A S G E T N I T C E L S D A O Y T H A M E S A R S T N L R E E N E T T B AT T E R Y A S L A L B A N Y S T REE T T P O E S RE I PA R K N P U I N E S T T L R E E T T RE E P I N W E CIT Y H A E T T E RE CARLISLE S T REE T T -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

CITY of HUBER HEIGHTS STATE of OHIO City Dog Park Committee Meeting Minutes March 29, 2018 6:00 P.M

Agenda Page 1 of 1 CITY OF HUBER HEIGHTS STATE OF OHIO City Dog Park Committee March 29, 2018 6:00 P.M. City Hall – 6131 Taylorsville Road – Council Chambers 1. Call Meeting To Order/Roll Call: 2. Approval of Minutes: A. March 22, 2018 3. Topics of Discussion: A. City Dog Park Planning and Discussion 4. Adjournment: https://destinyhosted.com/print_all.cfm?seq=3604&reloaded=true&id=48237 3/29/2018 CITY OF HUBER HEIGHTS STATE OF OHIO City Dog Park Committee Meeting Minutes March 29, 2018 6:00 P.M. City Hall – 6131 Taylorsville Road – City Council Chambers Meeting Started at 6:00pm 1. Call Meeting To Order/Roll Call: Members present: Bryan Detty, Keith Hensley, Vicki Dix, Nancy Byrge, Vincent King & Richard Shaw Members NOT present: Toni Webb • Nina Deam was resigned from the Committee 2. Approval of Minutes: No Minutes to Approval 3. Topics of Discussion: A. City Dog Park Planning and Discussion • Mr. King mentioned the “Meet Me at the Park” $20,000 Grant campaign. • Mr. Detty mentioned the Lowe’s communication. • Ms. Byrge discussed the March 29, 2018 email (Copy Enclosed) • Mr. Shaw discussed access to a Shared Drive for additional information. • Mr. King shared concerns regarding “Banning” smoking at the park as no park in Huber is currently banned. • Ms. Byrge suggested Benches inside and out of the park area. • Mr. Hensley and the committee discussed in length the optional sizes for the park. • Mr. Detty expressed interest in a limestone entrance area. • Mr. Hensley suggested the 100ft distance from the North line of the Neighbors and the School property line to the South. -

Lower Manhattan

WASHINGTON STREET IS 131/ CANAL STREETCanal Street M1 bus Chinatown M103 bus M YMCA M NQRW (weekday extension) HESTER STREET M20 bus Canal St Canal to W 147 St via to E 125 St via 103 20 Post Office 3 & Lexington Avs VESTRY STREET to W 63 St/Bway via Street 5 & Madison Avs 7 & 8 Avs VARICK STREET B= YORK ST AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 6 only6 Canal Street Firehouse ACE LISPENARD STREET Canal Street D= LAIGHT STREET HOLLAND AT&T Building Chinatown JMZ CANAL STREET TUNNEL Most Precious EXIT Health Clinic Blood Church COLLISTER STREET CANAL STREET WEST STREET Beach NY Chinese B BEACH STStreet Baptist Church 51 Park WALKER STREET St Barbara Eldridge St Manhattan Express Bus Service Chinese Greek Orthodox Synagogue HUDSON STREET ®0= Merchants’ Fifth Police Church Precinct FORSYTH STREET 94 Association MOTT STREET First N œ0= to Lower Manhattan ERICSSON PolicePL Chinese BOWERY Confucius M Precinct ∑0= 140 Community Plaza Center 22 WHITE ST M HUBERT STREET M9 bus to M PIKE STREET X Grand Central Terminal to Chinatown84 Eastern States CHURCH STREET Buddhist Temple Union Square 9 15 BEACH STREET Franklin Civic of America 25 Furnace Center NY Chinatown M15 bus NORTH MOORE STREET WEST BROADWAY World Financial Center Synagogue BAXTER STREET Transfiguration Franklin Archive BROADWAY NY City Senior Center Kindergarten to E 126 St FINN Civil & BAYARD STREET Asian Arts School FRANKLIN PL Municipal via 1 & 2 Avs SQUARE STREET CENTRE Center X Street Courthouse Upper East Side to FRANKLIN STREET CORTLANDT ALLEY 1 Buddhist Temple PS 124 90 Criminal Kuan Yin World -

550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1

City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT FULL FORM Please fill out, print and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (To Be Assigned by Lead Agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) 16DCP031M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (If Applicable) (e.g., Legislative Intro, CAPA, etc.) Pending 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC New York City Planning Commission DCP Manhattan Borough Office NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON NAME OF APPLICANT’S REPRESENTATIVE OR CONTACT PERSON Robert Dobruskin DCP: Edith Hsu-Chen (212-720-3437) Director, Environmental Assessment and Review Division Michael Sillerman, Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP ADDRESS ADDRESS 22 Reade Street, Room 4E 1177 Avenue of the Americas CITY STATE ZIP CITY STATE ZIP New York NY 10007 New York NY 10036 TELEPHONE FAX TELEPHONE FAX 212-720-3423 212-720-3495 212-715-7838 EMAIL ADDRESS EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3. Action Classification and Type SEQRA Classification UNLISTED TYPE I; SPECIFY CATEGORY (see 6 NYCRR 617.4 and NYC Executive Order 91 of 1977, as amended): 617.4(6)(v) Action Type (refer to Chapter 2, “Establishing the Analysis Framework” for guidance) LOCALIZED ACTION, SITE SPECIFIC LOCALIZED ACTION, SMALL AREA GENERIC ACTION 4. Project Description: The applicants, the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) and SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC, are requesting discretionary approvals (the “proposed actions”) that would facilitate the redevelopment of the St. -

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

Position Statement ESTABLISHING a NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT

APA New York Metro Chapter 121 West 27th Street, Suite 705 New York, NY 10001 Attention: David Fields Phone: (646) 963-9229 Position Statement ESTABLISHING A NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT for the HUDSON RIVER PARK The NY Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association is a professional, educational, and advocacy organization representing over 1,200 practicing planners and policy makers in New York City and its surrounding suburbs. We are part of a national association with a membership of 41,000 professionals and students who are engaged in programs and projects related to the physical, social and economic environment. In our role as a professional advocacy organization, we offer insights and recommendations on policy matters affecting issues such as housing, transportation and the environment. The Chapter has taken an interest in the proposal to form a Neighborhood Improvement District (NID) for the area surrounding the Hudson River Park. While we are generally in support of the proposal, we wish to point out a number of concerns we have with what appears to be an emerging trend of relying on alternative sources of funding for what should be a basic governmental responsibility. BACKGROUND The proposal for the NID was introduced by Friends of Hudson River Park, a private not- for-profit organization dedicated to raising funds for the “completion, care and enhancement” of the Park. Hudson River Park is a regional asset that not only serves the west side of Manhattan, but draws people from all around the metropolitan area. The creation of the Park led to a dramatic increase in property values along West Street, 10th, 11th & 12th Avenues and their intersecting streets. -

Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That's Off the Chain(PDF)

TIPS +tails SEPTEMBER 2012 Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That’s Off the Chain New York City’s many off-leash dog parks provide the perfect venue for a tail-wagging good time The start of fall is probably one of the most beautiful times to be outside in the City with your dog. Now that the dog days are wafting away on cooler breezes, it may be a great time to treat yourself and your pooch to a quality time dedicated to socializing, fun and freedom. Did you know New York City boasts more than 50 off-leash dog parks, each with its own charm and amenities ranging from nature trails to swimming pools? For a good time, keep this list of the top 25 handy and refer to it often. With it, you and your dog will never tire of a walk outside. 1. Carl Schurz Park Dog Run: East End Ave. between 12. Inwood Hill Park Dog Run: Dyckman St and Payson 24. Tompkins Square Park Dog Run: 1st Ave and Ave 84th and 89th St. Stroll along the East River after Ave. It’s a popular City park for both pooches and B between 7th and 10th. Soft mulch and fun times your pup mixes it up in two off-leash dog runs. pet owners, and there’s plenty of room to explore. await at this well-maintained off-leash park. 2. Central Park. Central Park is designated off-leash 13. J. Hood Wright Dog Run: Fort Washington & 25. Washington Square Park Dog Run: Washington for the hours of 9pm until 9am daily. -

Aroundmanhattan

Trump SoHo Hotel South Cove Statue of Liberty 3rd Avenue Peter J. Sharp Boat House Riverbank State Park Chelsea Piers One Madison Park Four Freedoms Park Eastwood Time Warner Center Butler Rogers Baskett Handel Architects and Mary Miss, Stanton Eckstut, F A Bartholdi, Richard M Hunt, 8 Spruce Street Rotation Bridge Robert A.M. Stern & Dattner Architects and 1 14 27 40 53 66 Cetra Ruddy 79 Louis Kahn 92 Sert, Jackson, & Assocs. 105 118 131 144 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Marner Architecture Rockwell Group Susan Child Gustave Eiffel Frank Gehry Thomas C. Clark Armand LeGardeur Abel Bainnson Butz 23 East 22nd Street Roosevelt Island 510 Main St. Columbus Circle Warren & Wetmore 246 Spring Street Battery Park City Liberty Island 135th St Bronx to E 129th 555 W 218th Street Hudson River -137th to 145 Sts 100 Eleventh Avenue Zucotti Park/ Battery Park & East River Waterfront Queens West / NY Presbyterian Hospital Gould Memorial Library & IRT Powerhouse (Con Ed) Travelers Group Waterside 2009 Addition: Pei Cobb Freed Park Avenue Bridge West Harlem Piers Park Jean Nouvel with Occupy Wall St Castle Clinton SHoP Architects, Ken Smith Hunters Point South Hall of Fame McKim Mead & White 2 15 Kohn Pedersen Fox 28 41 54 67 Davis, Brody & Assocs. 80 93 and Ballinger 106 Albert Pancoast Boiler 119 132 Barbara Wilks, Archipelago 145 Beyer Blinder Belle Cooper, Robertson & Partners Battery Park Battery Maritime Building to Pelli, Arquitectonica, SHoP, McKim, Mead, & White W 58th - 59th St 388 Greenwich Street FDR Drive between East 25th & 525 E. 68th Street connects Bronx to Park Ave W127th St & the Hudson River 100 11th Avenue Rutgers Slip 30th Streets Gantry Plaza Park Bronx Community College on Eleventh Avenue IAC Headquarters Holland Tunnel World Trade Center Site Whitehall Building Hospital for Riverbend Houses Brooklyn Bridge Park Citicorp Building Queens River House Kingsbridge Veterans Grant’s Tomb Hearst Tower Frank Gehry, Adamson Ventilation Towers Daniel Libeskind, Norman Foster, Henry Hardenbergh and Special Surgery Davis, Brody & Assocs. -

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

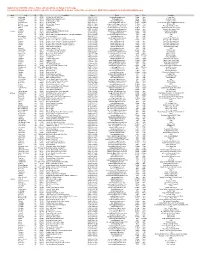

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston