2004 with Drummer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Gwilym Simcock

Gwilym Simcock Chick Corea simply calls him an "original. A creative genius", while Jamie Cullum raves about his playing: "I'll be watching our finest young piano-player Gwilym Simcock." Born 1981 in Wales, Simcock – now living in London –is undoubtedly right at the top of European jazz and considered one of the most gifted pianists and imaginative composers on the British scene. He took classical piano lessons at one of England's most renowned music schools from the age of three, building up a musical background that defines his playing to this day. He certainly could have become a successful classical pianist if he had not discovered Keith Jarrett's and Pat Metheny's music by the age of 15, finally drawing him into jazz. Having completed his studies at the Royal Academy of Music he is able to move effortlessly between jazz and classical. Simcock was acknowledged as a great talent very early on and soon got to play with stars like Dave Holland, Lee Konitz, Bob Mintzer and on Bill Bruford's "Earthworks". Winner of the Perrier Award, BBC Jazz Awards and British Jazz Awards in 2005, Simcock was the first BBC Radio 3 "New Generation Jazz Artist". He also was voted "Jazz Musician of the Year" at the 2007 Parliamentary Jazz Awards. The release of his ACT debut "Good Days at Schloss Elmau" (ACT 9501-2) early in 2011 marks his final breakthrough. Along with recordings by Adele, Katy B and James Blake, the solo piano album was nominated for the prestigious Mercury Prize as one of Great Britain's 12 best albums of the year. -

Singer Kendra Shank Pays Tribute to Spirited Music of Abbey Lincoln

Photo by John Abbott Photo by John Kendra Shank will bring the music of Abbey Lincoln to Lincoln June 5. Singer Kendra Shank pays tribute ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ to spirited music of Abbey Lincoln ○○○○○○○○○○○○ By Tom Ineck ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ April 2007 Vol. 12, Number 2 With her new release, “A Spirit File Photo Free: Abbey Lincoln Songbook,” singer Kendra Shank has taken on a daunting task—interpreting the music of one of the most idiosyn- cratic jazz singer-songwriters in his- ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ tory. In this issue of Jazz.... She and her longtime ensemble will bring the music of Lincoln to Prez Sez.........................................................2 Lincoln, Neb., June 5 in the open- Abbey Lincoln John Pizzarelli review........................6 ing concert of this year’s Jazz in Giacomo Gates/NJO review..................7 June series. this record were created there, on In a recent interview, Shank the gigs at that club. We would just Chick Corea/Gary Burton review...........8 talked about the recording and the try stuff and see what worked well Maria Schneider Orchestra review.....9 years it took to bring to fruition. and what didn’t work well,” she Mac McCune/NJO review......................10 Unlike many jazz musicians liv- said, pretty much describing the cre- Tomfoolery: Generous jazz calendar......11 ing in New York City, Shank has a ative process inherent in jazz mu- regular gig where she and the band sic. Harry “The Hipster” Gibson..................12 can work up new material and hone To Shank’s knowledge, no one Jazz on Disc reviews...........................14 their music to a fine edge. One Fri- else has ever attempted a full-length Discorama reviews..............................18 day a month, they appear at the 55 tribute to Lincoln’s very personal Letters to the Editor...............................19 Bar, Shank’s home away from music, although some of her tunes home for five years. -

It's All Good

SEPTEMBER 2014—ISSUE 149 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JASON MORAN IT’S ALL GOOD... CHARLIE IN MEMORIAMHADEN 1937-2014 JOE • SYLVIE • BOBBY • MATT • EVENT TEMPERLEY COURVOISIER NAUGHTON DENNIS CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2014 BILLY COBHAM SPECTRUM 40 ODEAN POPE, PHAROAH SANDERS, YOUN SUN NAH TALIB KWELI LIVE W/ BAND SEPT 2 - 7 JAMES CARTER, GERI ALLEN, REGGIE & ULF WAKENIUS DUO SEPT 18 - 19 WORKMAN, JEFF “TAIN” WATTS - LIVE ALBUM RECORDING SEPT 15 - 16 SEPT 9 - 14 ROY HARGROVE QUINTET THE COOKERS: DONALD HARRISON, KENNY WERNER: COALITION w/ CHICK COREA & THE VIGIL SEPT 20 - 21 BILLY HARPER, EDDIE HENDERSON, DAVID SÁNCHEZ, MIGUEL ZENÓN & SEPT 30 - OCT 5 DAVID WEISS, GEORGE CABLES, MORE - ALBUM RELEASE CECIL MCBEE, BILLY HART ALBUM RELEASE SEPT 23 - 24 SEPT 26 - 28 TY STEPHENS (8PM) / REBEL TUMBAO (10:30PM) SEPT 1 • MARK GUILIANA’S BEAT MUSIC - LABEL LAUNCH/RECORD RELEASE SHOW SEPT 8 GATO BARBIERI SEPT 17 • JANE BUNNETT & MAQUEQUE SEPT 22 • LOU DONALDSON QUARTET SEPT 25 LIL JOHN ROBERTS CD RELEASE SHOW (8PM) / THE REVELATIONS SALUTE BOBBY WOMACK (10:30PM) SEPT 29 SUNDAY BRUNCH MORDY FERBER TRIO SEPT 7 • THE DIZZY GILLESPIE™ ALL STARS SEPT 14 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES THE FLOWDOWN SEPT 5 • EAST GIPSY BAND w/ TIM RIES SEPT 6 • LEE HOGANS SEPT 12 • JOSH DAVID & JUDAH TRIBE SEPT 13 RABBI DARKSIDE SEPT 19 • LEX SADLER SEPT 20 • SUGABUSH SEPT 26 • BROWN RICE FAMILY SEPT 27 Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps with Hutch or different things like that. like things different or Hutch with sometimes. -

Simcock, Garland, Sirkis Simcock, Garland, Sirkis

Jubilee Release # 8 Simcock, Garland, Sirkis Lighthouse ACT 952 555---222 German Release DateDate:: March 30, 2012 Once upon a time … there was a lighthouse A celtic influinfluenceence surfaces on some of the trio's material,material, unsurprising given Simcock's birthplace (Bangor, North On England’s north east coast, just before the Scottish Wales) and Tim's musical history (incl. British Folk/Jazz group border, on an island near Whitley Bay, stands a gleaming 'Lammas' for many years). Strong, distinctive melodies and white lighthouse - St. Mary’s Lighthouse - which ascends into bounding folk-tinged rhythms underpin the music, along with the sky. The five hundred metres between the tiny island and many other influences from around the world and some the coast can only be crossed at low tide. When Tim Garland tributes to a few of the great musicians of recent British took on a job as composer-in-residence at nearby Newcastle contemporary music history. If St. Mary’s Lighthouse is a university he decided to buy a house - near the lighthouse. genuine sight, this Lighthouse is a major aural sight - a new “You enter this space and the first thing you notice is the chapter in lighthouse history. special acoustics. It's totally hollow inside. When the tide is in, the lighthouse stands in water and is cut off from the land 01 Space Junk: This was written after I did some work in and then all you can hear and see is the sea.” For the CD “If Ibiza with two great DJ's, Carl Cox and Yousef. -

Chick Willis Uk £3.25

ISSUE 163 WINTER 2020 CHICK WILLIS UK £3.25 Photo by Merlin Daleman CONTENTS Photo by CHRISTMAS STOCKING FILLERS Merlin Daleman CHICK WILLIS pictured at the Birmingham Jazz Festival. Chick makes an appearance in a new feature for Jazz BIG BEAR RECORDS CD OFFER Rag. We link up with Henry’s Blueshouse in Birmingham to EXCLUSIVELY FOR READERS OF THE JAZZ RAG present Henry’s Bluesletter (pages 32-33) ALL CDS £8 EACH OR THREE FOR £16 INCLUDING P&P 4 FESTIVAL IN TIME OF PLAGUE Birmingham, Sandwell and Westside Jazz Festival goes ahead 5 THE VIRUS IN NUMBERS JAZZ CITY UK VOLUME 2: THE JAM SESSIONS 6 ‘A TRUE NEW ORLEANS CHARACTER’ Coroner/trumpeter Frank Minyard Howard McCrary Various Artists Various Artists Lady Sings Potato Head 7 I GET A KICK OUT OF… Moments Like This Jazz City UK Volume 2 Jazz City UK Volume 1 The Blues Jazz Band Promoter John Billett Laughing at Life Stompin’ Around 8 COMPETITION: LOUIS ARMSTRONG 9 GOODBYE TO A STAR Roger Cotterrell on Peter King 11 BBC YOUNG JAZZ MUSICIAN OF THE YEAR 12 SUPERBLY SWINGING Alan Barnes remembers Dick Morrissey Remi Harris Trio Tipitina King Pleasure & Nomy Rosenberg Django’s Castle 14 FRENCH BOOGIE STAR Ninick Taking Care of The Biscuit Boys Nomy Rosenberg Trio with Bruce Adams Ron Simpson profiles Ben Toury Business Live At Last Swing Hotel du Vin 16 50 BY LOUIS Scott Yanow’s choice FIND US ON FACEBOOK 18 ROY WILLIAMS IN PICS The Jazz Rag now has its own Facebook page. For news of upcoming festivals, gigs and releases, 20 REFLECTING DREAMS Marilyn Mazur interviewed by Ron Simpson features from the archives, competitions and who knows what else, be sure to ‘like’ us. -

JAZZ EDUCATION in ISRAEL by LEE CAPLAN a Thesis Submitted to The

JAZZ EDUCATION IN ISRAEL by LEE CAPLAN A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research written under the direction of Dr. Henry Martin and approved by ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Newark, New Jersey May,2017 ©2017 Lee Caplan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS JAZZ EDUCATION IN ISRAEL By LEE CAPLAN Thesis Director Dr. Henry Martin Jazz Education in Israel is indebted to three key figures – Zvi Keren, Arnie Lawrence, and Mel Keller. This thesis explores how Jazz developed in Israel and the role education played. Jazz Education in Israel discusses the origin of educational programs such as the Rimon School of Jazz and Contemporary Music (1985) and the New School Jazz Program (1986). One question that was imperative to this study was attempting to discover exactly how Jazz became a cultural import and export within Israel. Through interviews included in this thesis, this study uncovers just that. The interviews include figures such as Tal Ronen, Dr. Arnon Palty, Dr. Alona Sagee, and Keren Yair Dagan. As technology gets more advanced and the world gets smaller, Jazz finds itself playing a larger role in humanity as a whole. iii Preface The idea for this thesis came to me when I was traveling abroad during the summer of 2015. I was enjoying sightseeing throughout the streets of Ben Yehuda Jerusalem contemplating topics when all of a sudden I came across a jam session. I went over to listen to the music and was extremely surprised to find musicians from all parts of Europe coming together in a small Jazz venue in Israel playing bebop standards at break-neck speeds. -

S Earthworks – Heavenly Bodies – an Expanded Collection

Bill Bruford’s Earthworks – Heavenly Bodies – An Expanded Collection (68:24 & 60:49, DCD, Digital, Summerfold/Cherry Red, 2019) Wem Bill Bruford bis zum heutigen Tag noch eine Unbekannte mit einigen Fragezeichen ist, dem sei gesagt, dass er eine wahre Größe in der Szene war bzw. ist. Seine Drum-Aktivitäten in der Vergangenheit reichten von Yes über UK bis King Crimson und sprechen somit eine eindeutige Sprache, die keinen Zweifel über seine Fähigkeiten zulassen. Nach seinen ursprünglich progressiven Ausflügen zog es den Drummer zuletzt verstärkt zum Jazz bzw. dem Jazz Rock, den er dann auch ausgiebig mit seiner Band Earthworks bis zu seinem Ruhestand 2009 durchlebte. Die Neuauflage seines erstmalig 1997 erschienenen Albums „Heavenly Bodies“ ist jetzt als Doppel CD erhältlich und umfasst 23 Titel mit insgesamt 129 Minuten anspruchsvoller Kost. Die Bonus CD beinhaltet unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen der Jahre 1998 bis 2005, während die erste CD ein umfangreiches Paket mit den größten Hits der Formation darstellt. Zum Schutz Ihrer persönlichen Daten ist die Verbindung zu YouTube blockiert worden. Klicken Sie auf Video laden, um die Blockierung zu YouTube aufzuheben. Durch das Laden des Videos akzeptieren Sie die Datenschutzbestimmungen von YouTube. Mehr Informationen zum Datenschutz von YouTube finden Sie hier Google – Datenschutzerklärung & Nutzungsbedingungen. YouTube Videos zukünftig nicht mehr blockieren. Video laden Mit von der Partie sind eine Vielzahl exzellenter Musiker, die mit Bruford dafür sorgen, das keine Langeweile aufkommt, also einfach brav zurücklehnen und chillen ist nicht. Diese Form von Jazz Rock fordert schon seinen Tribut, da ist eine Menge Aufmerksamkeit und eine Portion Ausdauer gefragt. Geboten wird Jazz Rock mit zeitweise komplexen, hörbar ungeraden Takten, unterstützt werden die Kompositionen durch Tasteninstrumente, raffinierte Bläsersätze und natürlich die beispiellose Schlagzeugarbeit Brufords. -

The Sirkis:Bialas Quartet EPK KEVIN

Sirkis/Bialas IQ EMOTIONAL GROOVY DYNAMIC MULTICULTURAL Asaf Sirkis drums / compositions Sylwia Bialas vocals / compositions Frank Harrison piano, keyboards Kevin Glasgow electric bass The Sirkis/Bialas International Quartet is a fresh new collaboration between Israeli UK-resident drummer/composer Asaf Sirkis, known for his work with the Lighthouse trio (ACT), Gilad Atzmon, Tim Garland, Larry Corryel, John Abercrombie & the Asaf Sirkis Trio, and Polish vocalist/composer extraordinaire Sylwia Bialas. The quartet features London based, scottish bassist Kevin Glasgow, and the acclaimed Frank Harrison on piano and keyboards (UK). With an emphasis on band interaction and sheer joy of playing, this band celebrates music from both collaborators, covering a wide range of influences such as contemporary classical music, Polish folk, South Indian & Middle Eastern musics as well as a wide range of dynamics – from the most delicate ballad all the way to high-energy electric virtuoso lines and everything in between. Expect soulful melodies, aerospheric sounds with strong grooves, a full colour electroacoustic jazz with an ethnic touch and some uncommonly used instruments and sound effects. The quartet`s latest album „Come To Me“ was released 2014 at the London Jazz Festival and the band has been touring in the UK and Europe since. Come To Me has been selected by Mark Sullivan at All About Jazz Website as one of the best albums of 2015. Click here to listen to the band‘s latest recording Photos by Gary Corbett P r e s s H i g h l i g h t s Sirkis/Bialas IQ Album`Come To Me` „The album consists of ten journeys, they are much more than tracks, which contain many moments of intense yearning, sorrow, happiness and love.“ „The music is highly emotional, with long-limbed melodies that unfold slowly, encircling the sound stage. -

The Mystery Orchestral Music by Tim Garland

presents THE MYSTERY ORCHESTRAL MUSIC BY TIM GARLAND The Northern Sinfonia Orchestra conducted by Clark Rundell Tim Garland - saxophones, bass flute Chick Corea - piano This seventy minute CD of orchestral music composed by Tim Garland features The Northern Sinfonia Orchestra with Garland and the legendary Chick Corea as soloists. The Mystery integrates new orchestral music with the contemporary jazz world in a way seldom achieved, the jazz and modern-classical elements being present in equal measure. Tim Garland studied classical composition at London's Guildhall School of Music. Craving the spontaneity of jazz, the impatient twenty year-old turned to the saxophone and for many years kept his compositions to those of a small-group nature. He was not comfortable imitating the jazz heroes of America however, so he established Lammas - a Celtic Roots/Jazz cross-over band - quite an innovation at the time. Lammas made five CDs and ran for ten years, and helped to establish Garland's reputation as an innovative and striking performer. Garland was also head-hunted by Ronnie Scott, joining his band for a short time in the nineties. Several recording projects followed, and in 1995 Garland's album Enter The Fire was released. For the first time Garland felt ready to acknowledge the influence of swing and the American mainstream, whilst continuing to hone his own characteristic compositions. This was the beginning of a surge forward in Garland's career, and a slow expansion back towards more through-composed and classically influenced music. Over the last ten years he has written prolifically for, and fronted bands of various sizes, including a trio with jazz virtuosi Geoff Keezer and Joe Locke (Storms/Nocturnes) and his nine-piece Underground Orchestra. -

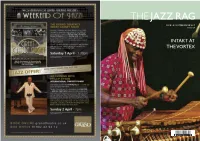

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 145 WINTER/SPRING 2017 UK £3.25 INTAKT AT THE VORTEX Photo by Stefan Postius CONTENTS INTAKT RECORDS (PAGE 13) IVORIAN ALY KEITA, MASTER OF THE BALAFON, IS AMONG THE STARS PERFORMING AT INTAKT RECORDS’ FESTIVAL AT THE VORTEX, LONDON. 4 NEWS 7 UPCOMING EVENTS 9 NAT HENTOFF THE GREAT JAZZ WRITER REMEMBERED 10 JAZZ CENTRE UK DIGBY FAIRWEATHER INTRODUCES A MAJOR NEW PROJECT 12 LAST OF THE GUNSLINGERS? SIMON SPILLETT STIRS UP DEBATE 14 ELLA AT 100 SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG SCOTT YANOW ON A NOTABLE CENTENARY THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY £17.50* 16 JAZZ RAG CHARTS CDS AND BOOKS Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. 18 JAZZ FESTIVALS MARCH-JUNE OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: EU £24 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £27 21 SOUTHPORT JAZZ FESTIVAL REVIEW Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC Please send to: 22 CD REVIEWS JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 31 BOOK REVIEW To pay by debit/credit card, visit www.paypal.me/bigbearmusic and enter the correct amount for your subscription 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 33 – AND COUNTING! Fax: 0121 454 9996 The listing of jazz festivals on pages 18-20 suggests a very healthy scene – and, to an Email: [email protected] extent, that is the case -, but doesn’t hint at the hard work, determination and Web: www.jazzrag.com enterprise needed to keep a jazz festival in operation over many years.