Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Liberia (Trc) Volume I: Findings and Determinations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Between the Lines: Crime and Victimization in Liberia

Liberia ARMeD ViOLeNCe aSSeSSMeNT Issue Brief Number 2 September 2011 Reading between the Lines Crime and Victimization in Liberia Eight years after the end of the civil been conducted for over two decades’ Blair, 2011; Dziewanski, 2011a). It con - war in 2003, Liberia witnessed large (Blair, 2011, p. 5). siders information on the types of improvements in security. As high- Together with local partners, the violence reported, how violence is lighted in the first Issue Brief of this Small Arms Survey conducted a nation- perpetrated, where it takes place, when series, people in Liberia generally feel wide household survey in 2010 to fill it occurs, and who represent the main much safer than in previous years, and some of the data gaps and to generate perpetrators and victims. The Issue Brief many Liberians consider development an evidence-based understanding of also presents examples of program- issues a more pressing concern than violence in post-war Liberia. This ming efforts prevent and reduce crime security threats (Small Arms Survey, second Issue Brief of five relies on the and violence. The main results of this 2011). At the individual household survey findings, key informant inter- study are: level, however, the picture is some- views with local representatives—in- what less positive. Despite the overall cluding city mayors, police officers, Almost one in seven households national improvement, many Liberians religious leaders, students, elders, and (13.5 per cent) reports that at least still worry that someone in their house- heads of grassroots organizations— one household member was the hold may become the victim of a crime. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Liberia Youth and Workforce Development Assessment

Desk Review for USAID/Liberia Liberia Youth and Workforce Development Assessment 5 September 2017 This document was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by Ms. Paige Mason with the support of Ms. Katya Fink for the USAID Liberia Strategic Analysis project under contract AID-669-C-16-00002. DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Acronyms............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF TABLES & FIGURES ......................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Executive summary.................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Questions ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Methods ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia: Analysis and Recommendations

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Community Engagement Student Work Education Student Work Spring 2021 The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia: Analysis and Recommendations Yamah Dolo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/soe_student_ce Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Education Commons, International Public Health Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons, and the Substance Abuse and Addiction Commons Running head: The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia 1 The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia: Analysis and Recommendations Yamah Dolo Master of Education in Community Engagement, Merrimack College May, 2021 The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia 2 MERRIMACK COLLEGE CAPSTONE PAPER SIGNATURE PAGE CAPSTONE SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF EDUCATION IN COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT CAPSTONE TITLE: The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia: Analysis and Recommendations AUTHOR: Yamah Dolo THE CAPSTONE PAPER HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION IN COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT. Audrey Falk, Ed.D. DIRECTOR, COMMUNITY SIGNATURE DATE ENGAGEMENT Sean McCarthy, Ed.D. INSTRUCTOR, CAPSTONE SIGNATURE DATE COURSE The Policy of Substance Abuse in Liberia 3 Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to all the Professors in the Community Engagement program; this project would not have been possible without your support and leadership, encouragement, and willingness to educate the 2021 cohort. To Dr. Sean McCarthy, thank you for taking the time, patience, and believing in the class of 2021, from the beginning to the end of the Policy Capstone. -

Report of Liberia, Oct 2016

Addressing Impunity for Rape in Liberia October 2016 i Abbreviations ACHPR African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights ACRWC African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child CAT Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CLO Case liaison officer CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities HRPS Human Rights and Protection Service, United Nations Mission in Liberia ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights INCHR Independent National Commission on Human Rights LNP Liberia National Police MOGCSP Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection1 NGO Non-governmental organization NHRAP National Human Rights Action Plan of Liberia TOE United Nations Team of Experts on the Rule of Law / Sexual Violence in Conflicts SEA Sexual exploitation and abuse SGBV Sexual and gender-based violence SGBVCU Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Crimes Unit UNMIL United Nations Mission in Liberia UPR Universal Periodic Review WACPS Women and Children Protection Section, Liberia National Police 1 Formerly known as the Ministry of Gender and Development. 2 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... -

Crime and Victimization in Liberia

Liberia ARMeD ViOLeNCe aSSeSSMeNT Issue Brief Number 2 September 2011 Reading between the Lines Crime and Victimization in Liberia Eight years after the end of the civil been conducted for over two decades’ Blair, 2011; Dziewanski, 2011a). It con - war in 2003, Liberia witnessed large (Blair, 2011, p. 5). siders information on the types of improvements in security. As high- Together with local partners, the violence reported, how violence is lighted in the first Issue Brief of this Small Arms Survey conducted a nation- perpetrated, where it takes place, when series, people in Liberia generally feel wide household survey in 2010 to fill it occurs, and who represent the main much safer than in previous years, and some of the data gaps and to generate perpetrators and victims. The Issue Brief many Liberians consider development an evidence-based understanding of also presents examples of program- issues a more pressing concern than violence in post-war Liberia. This ming efforts prevent and reduce crime security threats (Small Arms Survey, second Issue Brief of five relies on the and violence. The main results of this 2011). At the individual household survey findings, key informant inter- study are: level, however, the picture is some- views with local representatives—in- what less positive. Despite the overall cluding city mayors, police officers, Almost one in seven households national improvement, many Liberians religious leaders, students, elders, and (13.5 per cent) reports that at least still worry that someone in their house- heads of grassroots organizations— one household member was the hold may become the victim of a crime. -

Liberia Strategic Note 2014

Country Portfolio Evaluation Report COUNTRY NAME: Liberia Strategic Note 2014– 2017 Date of report 23 August 2018 Report version Final Report Name of the Evaluation Team Leader Rose GAWAYA, Social Policy Network (SPN) Name of the Evaluation Team Member – National Philecia Ross Martor Consultant [email protected] Name of the Evaluation Manager Milica TURNIC, UN Women Liberia Country Office Name of the Regional Evaluation Specialist Cyuma MBAYIHA, UN Women Regional Office Dakar, Senegal Contact details for this report [email protected] 1 Acknowledgements Evaluation Reference Group Normative Co-ordination Programme Embassy of Sweden FAO CJPS/SI Ministry of Justice (HRPD/MoS UN Women Educare Human Right Division) UNDP INCHR Ministry of Finance and UNDP/PBF LIFLEA Development Planning UNFPA Ministry of Justice Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection UNICEF Right & Rice Foundation Ministry of Internal Affairs WFP Rural Women Governance Commission UNMIL SOAP THINK WLCL WONGOSOL 1. Evaluation Team Rose Gawaya Team Leader Philecia Ross Martor National Consultant 2. UN Women Evaluation Management Group Cyuma Mbayiha Regional M & E Specialist, UN Women, West Africa Milica Turnic Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist, UN Women, Liberia Tikikel Alemu Deputy Country Representative, UN Women, Liberia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 1 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................... -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 9 PART I. MINISTRY OF JUSTICE – CENTRAL-------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 14 1. DEPARTMENT OF ADMINISTRATION AND PUBLIC SAFETY----------------------------------------- 15 A) Offices of the Deputy & Assistant Ministers for Administration and Public Safety ---------- 15 I) Constraints……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 16 II) Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………………… 17 B) HUMAN RESOURCE-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- 17 I) Achievements………………………………………………………………………………………………………………20 II) Challenges………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 20 III) Constraints……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 20 C) INTERNAL AUDITING----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- 20 I) Payroll and Personnel Management………………………………………………………………………………….… 20 II) Bank Reconciliation ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 21 III) Pre-Audit of Disbursements…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 21 IV) Prior Audit Recommendations………………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 V) Procurement………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 VI) Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 23 D) FINANCE ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 23 i) Reporting Period January 1st -

Addressing Impunity for Rape in Liberia October 2016

Addressing Impunity for Rape in Liberia October 2016 United Nations Mission in Liberia UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMOSSIONER FOR HUMAN UNMIL RIGHTS 2 2016 SGBV Report Farid Zarif Zeid bin Ra'ad al-Hussein SRSG, United Nations Mission in Liberia High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNMIL) (OHCHR) 2016 SGBV Report 3 Abbreviations ACHPR African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights ACRWC African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child CAT Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CLO Case liaison officer CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities HRPS Human Rights and Protection Service, United Nations Mission in Liberia ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights INCHR Independent National Commission on Human Rights LNP Liberia National Police MOGCSP Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection1 NGO Non-governmental organization NHRAP National Human Rights Action Plan of Liberia TOE United Nations Team of Experts on the Rule of Law / Sexual Violence in Conflicts SEA Sexual exploitation and abuse SGBV Sexual and gender-based violence SGBVCU Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Crimes Unit UNMIL United Nations Mission in Liberia UPR Universal Periodic Review WACPS Women and Children Protection Section, Liberia National Police 1 Formerly known as the Ministry of Gender and Development. 4 2016 SGBV Report 2016 SGBV Report 5 Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 7 3. -

Resurrecting the Rule of Law in Liberia

Maine Law Review Volume 60 Number 2 Symposium -- Nation-Building: A Article 19 Legal Architecture? June 2008 Resurrecting the Rule of Law In Liberia Jim Dube Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr Part of the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Jim Dube, Resurrecting the Rule of Law In Liberia, 60 Me. L. Rev. 575 (2008). Available at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr/vol60/iss2/19 This Special Section is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESURRECTING THE RULE OF LAW IN LIBERIA Jim Dube I. INTRODUCTION II. A BRIEF LEGAL HISTORY III. THE BRYANT CASE IV. CONCLUSION 576 MAINE LAW REVIEW [Vol. 60:2 RESURRECTING THE RULE OF LAW IN LIBERIA Jim Dube* I. INTRODUCTION The rule of law is more than a legal concept. It encompasses more than an established set of rules and legal institutions. In the case of Liberia, there can be no rule of law without the commitment of those relatively few people who administer those rules on behalf of a post-conflict state that has endured twenty-five years of civil war and exploitation. This Essay seeks to prove that existing legal architecture and institutions in a post-conflict state matter less to the rule of law than does the character of the people who run the legal system. -

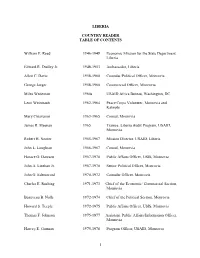

Table of Contents

LIBERIA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS William E. Reed 1946-1948 Economic Mission for the State Department, Liberia Edward R. Dudley Jr. 1948-1953 Ambassador, Liberia Allen C. Davis 1958-1960 Consular/Political Officer, Monrovia George Jaeger 1958-1960 Commercial Officer, Monrovia Miles Wedeman 1960s USAID Africa Bureau, Washington, DC Leon Weintraub 1962-1964 Peace Corps Volunteer, Monrovia and Kahnple Mary Chiavarini 1963-1965 Consul, Monrovia James R. Meenan 1965 Trainee, Liberia Audit Program, USAID, Monrovia Robert H. Nooter 1965-1967 Mission Director, USAID, Liberia John L. Loughran 1966-1967 Consul, Monrovia Horace G. Dawson 1967-1970 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Monrovia John A. Linehan Jr. 1967-1970 Senior Political Officer, Monrovia John G. Edensword 1970-1972 Consular Officer, Monrovia Charles E. Rushing 1971-1973 Chief of the Economic/ Commercial Section, Monrovia Beauveau B. Nalle 1972-1974 Chief of the Political Section, Monrovia Howard S. Teeple 1972-1975 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Monrovia Thomas F. Johnson 1975-1977 Assistant. Public Affairs/Information Officer, Monrovia Harvey E. Gutman 1975-1978 Program Officer, USAID, Monrovia 1 Beverly Carter, Jr. 1976-1979 Ambassador, Liberia Harold E. Horan 1976-1979 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Noel Marsh 1976-1980 Program Officer, USAID, Monrovia Richard C. Howland 1978 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC Julius W. Walker Jr. 1978-1981 Deputy Chief of Mission, Monrovia Parker W. Borg 1979-1981 Country Director, West African Affairs, Washington, DC Robert P. Smith 1979-1981 Ambassador, Liberia Peter David Eicher 1981-1983 Desk Officer, Washington, DC John D. Pielemeier 1981-1984 Deputy Director, USAID, Monrovia John E. -

10Edf En.Pdf

Acronyms ACP Africa, Caribbean, Pacific ACPA Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement AfDB African Development Bank AFL Armed Forces of Liberia AGOA African Growth Opportunity Act APIS Agricultural Policy Initiative Statement AU African Union BCE Bureau of Customs and Excise BoB Bureau of the Budget BMA Bureau of Maritime Affairs BWI Bretton Woods Institutions CA Contribution Agreement CAFF Children Associated with Fighting Forces CAO Chief Authorising Office CAP Consolidated Appeals Process CBL Central Bank of Liberia CDC Congress for Democratic Change (Political Party) CDP Community Development Programme CESD Community Empowerment and Skills Development CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CMC Contracts and Monopolies Commission CMCo Cash Management Committee CRC County Rehabilitation Component CSA Civil Service Agency CSP Country Strategy Paper CSO Civil Society Organisation DDRR Disarmament, Demobilisation, Reinsertion and Reintegration DFID Department for International Development DRC Danish Refugees Council EC European Commission ECHO European Commission Humanitarian Office ECSEL European Community Support Programme for Education in Liberia ECOMOG ECOWAS Military Observer Group ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States EDF European Development Programme EGSC Economic Governance Steering Committee EIB European Investment Bank EPA Economic Partnership Agreement EnPA Environment Protection Agency EPP Emergency Power Project ETF Elections Trust Fund EU European Union EUMS European Union Member States FDA Forestry Development Authority