A Dangerous Method [Motion Picture] J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludacris – Red Light District Brothers in Arms the Pacifier

Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ Ludacris – Red Light District Genre: Music Synopsis: Live concert from Amsterdam plus three music videos. Brothers In Arms Genre: Action Actors: David Carradine, Kenya Moore, Gabriel Casseus, Antwon Tanner, Raymond Cruz Director: Jean-Claude La Marre Synopsis: A crew of outlaws set out to rob the town boss who murdered one of their kinsmen. Driscoll is warned so his thugs surround the outlaws and soon there is a shootout. Set in the American West. The Pacifier Genre: Comedy Actors: Vin Diesel, Lauren Graham, Faith Ford, Brittany Snow, Max Theriot, Carol Kane, Brad Gardett Director: Adam Shankman Synopsis: The story of an undercover agent who, after failing to protect an important government scientist, learns the man's family is in danger. In an effort to redeem himself, he agrees to take care of the man's children only to discover that child care is his toughest mission yet. Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ The Killer Language: Japanese Genre: Action Actors: Chow Yun Fat Director: John Woo Synopsis: The story of an assassin, Jeffrey Chow (aka Mickey Mouse) who takes one last job so he can retire and care for his girlfriend Jenny. When his employers betray him, he reluctantly joins forces with Inspector Lee (aka Dumbo), the cop who is pursuing him. -

The 48 Stars That People Like Less Than Anne Hathaway by Nate Jones

The 48 Stars That People Like Less Than Anne Hathaway By Nate Jones Spend a few minutes reading blog comments, and you might assume that Anne Hathaway’s approval rating falls somewhere between that of Boko Haram and paper cuts — but you'd actually be completely wrong. According to E-Poll likability data we factored into Vulture's Most Valuable Stars list, the braying hordes of Hathaway haters are merely a very vocal minority. The numbers say that most people actually like her. Even more shocking? Who they like her more than. In calculating their E-Score Celebrity rankings, E-Poll asked people how much they like a particular celebrity on a six-point scale, which ranged from "like a lot" to "dislike a lot." The resulting Likability percentage is the number of respondents who indicated they either "like" Anne Hathaway or "like Anne Hathaway a lot." Hathaway's 2014 Likability percentage was 67 percent — up from 66 percent in 2013 — which doesn't quite make her Will Smith (85 percent), Sandra Bullock (83 percent), Jennifer Lawrence (76 percent), or even Liam Neeson (79 percent), but it does put her well above plenty of stars whose appeal has never been so furiously impugned on Twitter. Why? Well, why not? Anne Hathaway is a talented actress and seemingly a nice person. The objections to her boiled down to two main points: She tries too hard, and she's overexposed. But she's been absent from the screen since 2012'sLes Misérables, so it's hard to call her overexposed now. And trying too hard isn't the worst thing in the world, especially when you consider the alternative. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

Nikωletta Skarlatos Make up Designer / Make up Department Head Journeyman Makeup Artist Film & Television

NIKΩLETTA SKARLATOS MAKE UP DESIGNER / MAKE UP DEPARTMENT HEAD JOURNEYMAN MAKEUP ARTIST FILM & TELEVISION FUTURE MAN (Pilot, Seasons 1 and 2) (Make-up Department Head, Make-up Designer) Director: Seth Rogan & Evan Goldberg Production Company: Point Grey Pictures Cast: Josh Hutcherson, Eliza Coupe, Derek Wilson, Glenne Headley, Ed Begley Jr. NAPPILY EVER AFTER (Make-up Department Head, Make-up Designer) Personal: Sanaa Lathan & Lynne Whitfield, Director: Haifaa Al-Mansour Production Company: Netflix Cast: Sanaa Lathan, Lynne Whitfield, Ricky Whittle, Lyriq Bent, Ernie Hudson FREE STATE OF JONES (Make-up Department Head, Makeup Designer) Director: Gary Ross Production Company: Bluegrass Films Cast: Matthew McConaughey, Keri Russell, Mahershala Ali, Gugu Mbatha-Raw THE HUNGER GAMES: MOCKINGJAY PART 2 (Make-up Department Head) Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Lionsgate Cast: Jennifer Lawrence, Mahershala Ali, Liam Hemsworth, Josh Hutcherson, Elizabeth Banks, Woody Harrelson, Phillip Seymour Hoffmann, Donald Sutherland THE PERFECT GUY (Make-up Department Head, Make-up Designer) Director: David Rosenthal Production Company: Screen Gems Cast: Sanaa Lathan, Michael Ealy, Morris Chestnut, Charles Dutton LUX ARTISTS | 1 THE HUNGER GAMES: MOCKINGJAY PART 1 (Make-up Department Head) Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Lionsgate Cast: Jennifer Lawrence. Personal: Liam Hemsworth, Josh Hutcherson, Elizabeth Banks, Woody Harrelson, Mahershala Ali Nominated, Best Period and/or Character Make-up, Make-up and Hair Guild Awards (2015) SOLACE (Makeup Department Head, Makeup Designer) Director: Afonso Poyart Production Company: Eden Rock Media Cast: Anthony Hopkins, Colin Farrell, Abbie Cornish, Jeffrey Dean Morgan THE HUNGER GAMES: CATCHING FIRE (Key Make-up Artist) Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Lionsgate Cast: Jennifer Lawrence. -

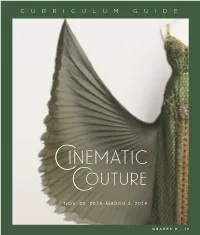

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

A DANGEROUS METHOD a Sony Pictures Classics Presentation a Jeremy Thomas Production

MOVIE REVIEW Afr J Psychiatry 2012;15:363 A DANGEROUS METHOD A Sony Pictures Classics Presentation A Jeremy Thomas Production. Directed by David Cronenberg Film reviewed by Franco P. Visser As a clinician I always found psychoanalysis and considers the volumes of ethical rules and psychoanalytic theory to be boring, too intellectual regulations that govern our clinical practice. Jung and overly intense. Except for the occasional was a married man with children at the time. As if Freudian slip, transference encountered in therapy, this was not transgression enough, Jung also the odd dream analysis around the dinner table or became Spielrein’s advisor on her dissertation in discussing the taboos of adult sexuality I rarely her studies as a psychotherapist. After Jung’s venture out into the field of classic psychoanalysis. attempts to re-establish the boundaries of the I have come to realise that my stance towards doctor-patient relationship with Spielrein, she psychoanalysis mainly has to do with a lack of reacts negatively and contacts Freud, confessing knowledge and specialist training on my part in everything about her relationship with Jung to him. this area of psychology. I will also not deny that I Freud in turn uses the information that Spielrein find some of the aspects of Sigmund Freud’s provided in pressuring Jung into accepting his theory and methods highly intriguing and at times views and methods on the psychological a spark of curiosity makes me jump into the pool functioning of humans, and it is not long before the of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic theory and two great minds part ways in addition to Spielrein ‘swim’ around a bit – mainly by means of reading or surfing the going her own way. -

Press-Release-The-Endings.Pdf

Publication Date: September 4, 2018 Media Contact: Diane Levinson, Publicity [email protected] 212.354.8840 x248 The Endings Photographic Stories of Love, Loss, Heartbreak, and Beginning Again By Caitlin Cronenberg and Jessica Ennis • Foreword by Mary Harron 11 x 8 in, 136pp, Hardcover, Photographs throughout ISBN 978‐1‐4521‐5568‐5, $29.95 Featuring some of today’s most celebrated actresses, including Julianne Moore, Alison Pill, and Imogen Poots, the photographic vignettes in The Endings capture female characters in the throes of emotional transformation. Photographer Caitlin Cronenberg and art director Jessica Ennis created stories of heartbreak, relationship endings, and new beginnings—fictional but often inspired by real life—and set out to convey the raw emotions that are exposed in these most vulnerable states. Cronenberg and Ennis collaborated with each actress to develop a character, build the world she inhabits, and then photograph her as she lived the role before the camera. Patricia Clarkson depicts a woman meeting her younger lover in the campus library—even though they both know the relationship has been over since before it even began. Juno Temple portrays a broken‐hearted woman who engages in reckless and self‐destructive behavior to numb the sadness she feels. Keira Knightley ritualistically cleanses herself and her home after the death of her great love. Also featured are Jennifer Jason Leigh, Danielle Brooks, Tessa Thompson, Noomi Rapace, and many more. These intimate images combine the lush beauty and rich details of fashion photographs with the drama and narrative energy of film stills. Telling stories of sadness, loneliness, anger, relief, rebirth, freedom, and happiness, they are about relationship endings, but they are also about beginnings. -

Symbols of Transformation, Phenomenology, and Magic Mountain

Journal of Jungian Scholarly Studies Vol. 7, No. 3, 2011 Symbols of Transformation, Phenomenology, and Magic Mountain Gary Brown, Ph.D. On Volume I In celebrating the centennial of Carl Jung’s Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido, which was published in 1911-12, we must note the book’s complex history. Not only did the book set in motion his complicated break from Freud, who finally in 1913 wrote to Jung: “Take your full freedom and spare me your supposed ‘tokens of friendship’” (Bair 238), but having traced in it the mythical fantasies of a liberated American woman named Miss Frank Miller, whose case study had been published by the Swiss psychiatrist Théodore Flournoy, Jung realized that unlike Miss Miller, he was unaware of the myths he might be living in his own life. Since he had argued that only mythical imagos (his original term for archetypes) could release one from the domain of instinct, there had to be myths of which he was ignorant operating in his own development. It was especially important for him to learn these since he had argued that Miss Miller was headed for a schizophrenic breakdown without increased awareness of her mythic processes. Yet she was ahead of him. His awareness of this deficiency sparked his return to journaling, which, as John Beebe has pointed out in “The Red Book as a Work of Conscience, ” Jung had abandoned for over a decade while focusing on his worldly accomplishments. This return to journaling yielded the famous, recently published Red Book. Jung attributes his increased understanding of the stages of psychic processes to his practice of active imagination in this journal. -

Theoretical and Clinical Contributions of Sabina Spielrein

APAXXX10.1177/0003065115599989Adrienne HarrisTheoretical and Clinical Contributions of Sabina Spielrein 599989research-article2015 j a P a Adrienne Harris XX/X “LanguAGE IS THERE TO BEWILDER ITSELF AND OThers”: TheoreTICAL AND CLINICAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF SABINA SPIELREIN Keywords: psychoanalysis, Sabina Spielrein, Freud, Jung, language, Piaget, Vygotsky here are many ways to begin this story. On August 18, 1904, a T young Russian woman of nineteen is admitted to the Burghölzli Hospital. She is described as disturbed, hysterical, psychotic, volatile. She is Jung’s first patient and her transference to him was almost imme- diately passionate and highly erotized. After her release from the hospital that relationship is fatally compromised by Jung’s erotic involvement with her. Later she is caught up in the conflicts and breakdown of the relationship of Freud and Jung. We know this version of Sabina Spielrein’s entrance into the medical and psychoanalytic worlds of Europe from films and some early biogra- phies, from her letters and diaries written in the period 1906–1907,and even from her psychiatric records (Covington and Wharton 2003, pp. 79–108). Spielrein has been cast as a young madwoman, later involved Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology, NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis. A timeline to accompany this paper is available online at apa.sagepub.com. An earlier version of this paper was given as a plenary address at the Winter Meeting of the American Psychoanalytic Association, New York, January 2015. The author is indebted to many helpful readers: Ken Corbett, Steven Cooper, Donald Moss, Wendy Olesker, Bonnie Litowitz, and John Launer. -

Sabina Spielrein

1 Sabina Spielrein A Life and Legacy Explored There is no death in remembrance. —Kathleen Kent, The Heretic’s Daughter abina Spielrein (often transliterated as Shpilrein or Spilrein) was born on SNovember 7, 1885, in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, into a Jewish family of seven: one sister, Emily; three brothers, Jan, Isaac, and Emil; and a businessman father, Nikolai Spielrein, and his wife, Eva. Spielrein was highly encouraged in her education and, unlike many young girls at the time, was afforded lessons in Warsaw, though her youth is often characterized as a troubled one, a time when her mother was emotionally unavailable and her father exerted immense authority over the household.1 However, Spielrein was a bright and intelligent child, and as a budding scientist, she kept liquids in jars expecting “the big creation” to take place in her near future.2 Remembering her early desire to create life, Spielrein once noted: “I was an alchemist.”3 Sadly, the death of Emily, who died at six years old, sent Spielrein into a dizzying confrontation with mortality at the tender age of fifteen. This loss, coupled with confusing abuse at the hands of her father—dis- cussed in the next chapter—spun her into a period of turmoil for which she was institutionalized. In August 1904, at age nineteen, she was sent to the Burghölzli Clinic in Zurich, Switzerland, where she became a patient of a then twenty-nine-year-old and married Dr. Carl Jung. She was to be one of his 9 © 2017 State University of New York Press, Albany 10 Sabina Spielrein first patients, subsequently diagnosed with “hysteria” and exhibiting symptoms of extreme emotional duress, such as screaming, repetitively sticking out her tongue, and shaking.4 She was a guinea pig for a new “talking cure,” based on free association, dream interpretation, and talk therapy, as innovated by Dr. -

The Hollywood Reporter November 2015

Reese Witherspoon (right) with makeup artist Molly R. Stern Photographed by Miller Mobley on Nov. 5 at Studio 1342 in Los Angeles “ A few years ago, I was like, ‘I don’t like these lines on my face,’ and Molly goes, ‘Um, those are smile lines. Don’t feel bad about that,’ ” says Witherspoon. “She makes me feel better about how I look and how I’m changing and makes me feel like aging is beautiful.” Styling by Carol McColgin On Witherspoon: Dries Van Noten top. On Stern: m.r.s. top. Beauty in the eye of the beholder? No, today, beauty is in the eye of the Internet. This, 2015, was the year that beauty went fully social, when A-listers valued their looks according to their “likes” and one Instagram post could connect with millions of followers. Case in point: the Ali MacGraw-esque look created for Kendall Jenner (THR beauty moment No. 9) by hairstylist Jen Atkin. Jenner, 20, landed an Estee Lauder con- tract based partly on her social-media popularity (40.9 million followers on Instagram, 13.3 million on Twitter) as brands slavishly chase the Snapchat generation. Other social-media slam- dunks? Lupita Nyong’o’s fluffy donut bun at the Cannes Film Festival by hairstylist Vernon Francois (No. 2) garnered its own hashtag (“They're calling it a #fronut,” the actress said on Instagram. “I like that”); THR cover star Taraji P. Henson’s diva dyna- mism on Fox’s Empire (No. 1) spawns thousands of YouTube tutorials on how to look like Cookie Lyon; and Cara Delevingne’s 22.2 million Instagram followers just might have something do with high-end brow products flying off the shelves. -

Carl Gustav Jung's Pivotal Encounter with Sigmund Freud During Their Journey to America

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 54 Number 2 Article 4 6-2018 The Psychological Odyssey of 1909: Carl Gustav Jung's Pivotal Encounter with Sigmund Freud during their Journey to America William E. Herman Axel Fair-Schulz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Herman, William E. and Fair-Schulz, Axel (2018) "The Psychological Odyssey of 1909: Carl Gustav Jung's Pivotal Encounter with Sigmund Freud during their Journey to America," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 54 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol54/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Herman and Fair-Schulz: The Psychological Odyssey of 1909: The Psychological Odyssey of 1909: Carl Gustav Jung's Pivotal Encounter with Sigmund Freud during their Journey to America by William E. Herman and Axel Fair-Schulz The year 1909 proved decisive for our relationship. - Carl Gustav Jung's autobiography. Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1961) M any volumes in the scholarly literature explore the complex evolution of the relationship between Carl Gustav Jung and Sigmund Freud as well as the eventual split between these two influential contributors to psychoanalytic thought and more generally to the field of psychology and other academic fields/professions. The events that transpired during the seven-week journey from Europe to America and back in the autumn of 1909 would serve as a catalyst to not only re-direct the lives of Jung and Freud along different paths, but also re-shape the roadmap of psychoanalytic thinking, clinical applications, and psychology.