The Shaughraun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Alive

THE NIGHT ALIVE BY CONOR MCPHERSON DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. THE NIGHT ALIVE Copyright © 2014, Conor McPherson All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE NIGHT ALIVE is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE NIGHT ALIVE are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Curtis Brown, Ltd. -

Cause Célèbre by Terence Rattigan

Cause Célèbre by Terence Rattigan Teachers’ Resource Pack Researched & written by Ellen Groves & Anne Langford 1 Cause CélèBRE – Teaching Resources Cause Célèbre SUBTITLE Cause Célèbre at The Old Vic 3 Sir Terence Rattigan : His Story 4 Chronology: Rattigan’s Career 5 Synopsis 6 What does cause célèbre mean? 8 Character breakdown 8 Theatrical context of the play 10 Historical context of the play 11 The ‘True’ story 12 Crimes of passion: Case Studies 13 Modern parallel case: OJ Simpson 15 Women and the Criminal Justice system 16 Death penalty in the UK / Around the world 17 In Conversation with... Niamh Cusack 19 Freddie Fox 21 Richard Teverson 23 Rehearsal Notes from the Assistant Director Eleanor While 24 Bibliography 26 2 cause célèbre by terence rattigan Lucy Black Timothy Carlton Simon Chandler Richard Clifford Oliver Coopersmith Niamh Cusack Anne‐Marie Duff Rory Fleck‐Byrne Joan Webster EranFis RaGenbury John Davenport Croom ‐ Johnson Christopher Edith Davenport Klma RaGenbury Montague & Randolph Browne Freddie Fox Jenny Galloway Patrick Godfrey Nicholas Jones Tommy McDonnell Lucy Robinson Tristan Shepherd Richard Teverson Tony Davenport Irene Riggs Judge O'Connor George Wood Stella Morrison Clerk of Court Casswell @nderstudy responsibiliAes Lucy Black: Edith Davenport & Klma RaGenbury Rory Fleck Byrne: George Wood & Casswell Tristan Shepherd:Tony Davenport & Randolph Browen & Montague Richard Teverson: O’Connor & Croom Johnson Sarah Waddell: Stella Morrison & Irene Riggs & Joan Webster & Clerk of Court Michael Webber: EranFis RaGenbury & Porter Sarah Waddell Michael Webber Tristram Wymark Tristram Wymark: John Davenport & Judge & Sergeant Bagwell Warder Sergeant Bagwell Porter 3 Cause CélèBRE – Teaching Resources Sir Terence Rattigan His Story Sir Terence Mervyn Rattigan was born in Kensington, London on 10 June 1911 and died of cancer on 30 November 1977. -

About the Bridge Theatre

Running time 2 hours and 15 minutes, no interval. Please note, this production contains strobe lighting and scenes of a violent and bloody nature. First performance at Bridge Theatre on 20 January 2018, broadcast live on 22 March 2018 Julius Caesar DAVID CALDER About the Bridge Theatre Calpurnia / Varro WENDY KWEH Marcus Brutus BEN WHISHAW The Bridge Theatre was founded by Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr Portia LEAPHIA DARKO on leaving the National Theatre after 12 years. The theatre has Lucius / Street Band / Cinna, a poet FRED FERGUS a 900-seat adaptable auditorium designed to answer the needs Caius Cassius MICHELLE FAIRLEY of contemporary audiences and theatre-makers that is capable Mark Antony DAVID MORRISSEY of responding to shows with different formats (end-stage, thrust- stage and promenade). It is the first wholly new theatre of scale Octavius / Street Band KIT YOUNG to be added to London’s commercial theatre sector in 80 years. Lepidus / Caius Ligarius / Soothsayer MARK PENFOLD The Bridge was designed by Steve Tompkins and Roger Watts of Casca ADJOA ANDOH Haworth Tompkins Architects (winner of the 2014 Stirling Prize). Cinna, a conspirator NICK SAMPSON Decius Brutus LEILA FARZAD Metellus Cimber HANNAH STOKELY Trebonius / Street Band ABRAHAM POPOOLA Connect with us Flavius / Popilius Lena SID SAGAR Marullus / Artemidorus ROSIE EDE Join in the conversation about #JuliusCaesar Philo / Street Band / Claudius ZACHARY HART ntlive.com/signup facebook.com/ntlive @ntlive Other citizens and plebeians played by members of the company We hope you enjoy your National Theatre Live screening. We make every attempt to replicate the theatre experience as Director NICHOLAS HYTNER closely as possible for your enjoyment. -

Conor Mcpherson 88 Min., 1.85:1, 35Mm

Mongrel Media Presents THE ECLIPSE A film by Conor McPherson 88 min., 1.85:1, 35mm (88min., Ireland, 2009) www.theeclipsefilm.com Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS THE ECLIPSE tells the story of Michael Farr (Ciarán Hinds), a teacher raising his two kids alone since his wife died two years earlier. Lately he has been seeing and hearing strange things late at night in his house. He isn't sure if he is simply having terrifying nightmares or if his house is haunted. Each year, the seaside town where Michael lives hosts an international literary festival, attracting writers from all over the world. Michael works as a volunteer for the festival and is assigned the attractive Lena Morelle (Iben Hjejle), an author of books about ghosts and the supernatural, to look after. They become friendly and he eagerly tells her of his experiences. For the first time he has met someone who can accept the reality of what has been happening to him. However, Lena’s attention is pulled elsewhere. She has come to the festival at the bidding of world-renowned novelist Nicholas Holden (Aidan Quinn), with whom she had a brief affair the previous year. He has fallen in love with Lena and is going through a turbulent time, eager to leave his wife to be with her. -

What Ever Happened to In-Yer-Face Theatre?

What Ever Happened to in-yer-face theatre? Aleks SIERZ (Theatre Critic and Visiting Research Fellow, Rose Bruford College) “I have one ambition – to write a book that will hold good for ten years afterwards.” Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise • Tuesday, 23 February 1999; Brixton, south London; morning. A Victorian terraced house in a road with no trees. Inside, a cloud of acrid dust rises from the ground floor. Two workmen are demolishing the wall that separates the dining room from the living room. They sweat; they curse; they sing; they laugh. The floor is covered in plaster, wooden slats, torn paper and lots of dust. Dust hangs in the air. Upstairs, Aleks is hiding from the disruption. He is sitting at his desk. His partner Lia is on a train, travelling across the city to deliver a lecture at the University of East London. Suddenly, the phone rings. It’s her. And she tells him that Sarah Kane is dead. She’s just seen the playwright’s photograph in the newspaper and read the story, straining to see over someone’s shoulder. Aleks immediately runs out, buys a newspaper, then phones playwright Mark Ravenhill, a friend of Kane’s. He gets in touch with Mel Kenyon, her agent. Yes, it’s true: Kane, who suffered from depression for much of her life, has committed suicide. She is just twenty-eight years old. Her celebrity status, her central role in the history of contemporary British theatre, is attested by the obituaries published by all the major newspapers. Aleks returns to his desk. -

Applause Magazine, Applause Building, 68 Long Acre, London WC2E 9JQ

1 GENE WIL Laughing all the way to the 23rd Making a difference LONDON'S THEATRE CRITI Are they going soft? PIUS SAVE £££ on your theatre tickets ,~~ 1~~EGm~ Gf1ll~ G~rick ~he ~ ~ e,London f F~[[ IIC~[I with ever~ full price ticket purchased ~t £23.50 Phone 0171-312 1991 9 771364 763009 Editor's Letter 'ThFl rul )U -; lmalid' was a phrase coined by the playwright and humourl:'t G eorge S. Kaufman to describe the ailing but always ~t:"o lh e m Broadway Theatre in the late 1930' s . " \\ . ;t" )ur ul\'n 'fabulous invalid' - the West End - seems in danger of 'e:' .m :: Lw er from lack of nourishmem, let' s hope that, like Broadway - presently in re . \ ,'1 'n - it too is resilient enough to make a comple te recovery and confound the r .: i " \\' ho accuse it of being an en vironmenta lly no-go area whose theatrical x ;'lrJ io n" refuse to stretch beyond tired reviva ls and boulevard bon-bons. I i, clUite true that the season just past has hardly been a vintage one. And while there is no question that the subsidised sector attracts new plays that, =5 'ears ago would a lmost certainly have found their way o nto Shaftes bury Avenue, l ere is, I am convinced, enough vitality and ingenuity left amo ng London's main -s tream producers to confirm that reports of the West End's te rminal dec line ;:m: greatly exaggerated. I have been a profeSSi onal reviewer long enough to appreciate the cyclical nature of the business. -

El Ecosistema Narrativo Transmedia De Canción De Hielo Y Fuego”

UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA ESCOLA POLITE CNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual “El ecosistema narrativo transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Jaume Mora Ribera Tutor/a: Nadia Alonso López Raúl Terol Bolinches GANDIA, 2019 1 Resumen Sagas como Star Wars o Pokémon son mundialmente conocidas. Esta popularidad no es solo cuestión de extensión sino también de edad. Niñas/os, jóvenes y adultas/os han podido conocer estos mundos gracias a la diversidad de medios que acaparan. Sin embargo, esta diversidad mediática no consiste en una adaptación. Cada una de estas obras amplia el universo que se dio a conocer en un primer momento con otra historia. Este conjunto de historias en diversos medios ofrece una narrativa fragmentada que ayuda a conocer y sumergirse de lleno en el universo narrativo. Pero a su vez cada una de las historias no precisa de las demás para llegar al usuario. El mundo narrativo resultante también es atractivo para otros usuarios que toman parte de mismo creando sus propias aportaciones. A esto se le conoce como narrativa transmedia y lleva siendo objeto de estudio desde principios de siglo. Este trabajo consiste en el estudio de caso transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego la saga de novelas que posteriormente se adaptó a la televisión como Juego de Tronos y que ha sido causa de un fenómeno fan durante la presente década. Palabras clave: Canción de Hielo y Fuego, Juego de Tronos, fenómeno fan, transmedia, narrativa Summary Star Wars or Pokémon are worldwide knowledge sagas. This popularity not just spreads all over the world but also over an age. -

June 17 – Jan 18 How to Book the Plays

June 17 – Jan 18 How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm Saint George and Network Pinocchio for the following week’s performances. the Dragon 4 Nov – 24 Mar 1 Dec – 7 Apr Day Tickets 4 Oct – 2 Dec £18 / £15 tickets available in person on the day of the performance. No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Access symbols used in this brochure CAP Captioned AD Audio-Described TT Touch Tour Relaxed Performance Beginning Follies Jane Eyre 5 Oct – 14 Nov 22 Aug – 3 Jan 26 Sep – 21 Oct TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre Partner for Innovation Partner for Learning Sponsored by in partnership with Partner for Connectivity Outdoor Media Partner Official Airline Official Hotel Partner Oslo Common The Majority 5 – 23 Sep 30 May – 5 Aug 11 – 28 Aug Workshops Partner The National Theatre’s Supporter for new writing Pouring Partner International Hotel Partner Image Partner for Lighting and Energy Sponsor of NT Live in the UK TBC Angels in America Mosquitoes Amadeus Playing until 19 Aug 18 July – 28 Sep Playing from 11 Jan 2 3 OCTOBER Wed 4 7.30 Thu 5 7.30 Fri 6 7.30 A folk tale for an Sat 7 7.30 Saint George and Mon 9 7.30 uneasy nation. -

Interweaving the Local and the Global in Conor Mcpherson’S the Weir

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-3, Issue-7, Jul.-2017 http://iraj.in INTERWEAVING THE LOCAL AND THE GLOBAL IN CONOR MCPHERSON’S THE WEIR MAHA ALATAWI School of English, drama, and Film Email: [email protected] Abstract- Focusing on the Irish playwright Conor McPherson’s the Weir, this paper explores how late- twentieth and early twenty-first century Irish drama – set within local places and shaped by the role of the supernatural – offers new ways in which to consider the relations between the national and the global. McPherson’s plays represent the interests of Ireland in specific time periods and places but have broader meaning and significance as they offer insight into the human condition. History and the supernatural are prevalent themes of McPherson’s works – he incorporates older traditions of ghost stories and storytelling – yet places them in a modern world. This paper argues for a realism that is grounded in the wider recognition of changing global, social and cultural conditions. Yet within these, certain human weaknesses and behavioural patterns remain static. In The Ethos of a Late-Modern Citizen, White suggests that changing democratic trends in Western societies asks for us to re-examine our role as citizens. White frames his theoretical approach by asking ‘what sort of "characteristic spirit" or "sentiment" should we be trying to cultivate as we seek to confront the deep challenges of late- modern life?’; citizens and minds of the future can no longer be inward looking or inward focused, but equally, as McPherson suggests in his plays, citizens rely on the personal associations and past experiences in order to forge an identity. -

NTL-2017-Hamlet-Program.Pdf

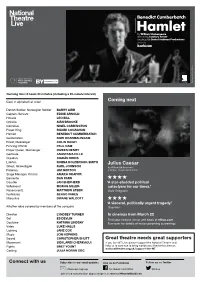

presented by Photograph by Johan Persson Running time: 3 hours 20 minutes (including a 20-minute interval) Cast, in alphabetical order Coming next Danish Soldier, Norwegian Soldier BARRY AIRD Captain, Servant EDDIE ARNOLD Horatio LEO BILL Ophelia SIÂN BROOKE Cornelius NIGEL CARRINGTON Player King RUAIRI CONAGHAN Hamlet BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Guildenstern RUDI DHARMALINGAM Priest, Messenger COLIN HAIGH Fencing Offi cial PAUL HAM Player Queen, Messenger DIVEEN HENRY Gertrude ANASTASIA HILLE Claudius CIARÁN HINDS Laertes KOBNA HOLDBROOK-SMITH Julius Caesar Ghost, Gravedigger KARL JOHNSON by William Shakespeare Polonius JIM NORTON a Bridge Theatre production Stage Manager, Offi cial AMAKA OKAFOR Barnardo DAN PARR HHHH Courtier JAN SHEPHERD ‘ A star-studded political Voltemand MORAG SILLER cataclysm for our times.’ Rosencrantz MATTHEW STEER Daily Telegraph Fortinbras SERGO VARES Marcellus DWANE WALCOTT HHHH ‘ A visceral, politically urgent tragedy.’ All other roles covered by members of the company Guardian Director LYNDSEY TURNER In cinemas from March 22 Set ES DEVLIN Find your nearest venue and book at ntlive.com Costume KATRINA LINDSAY Turn over for details of more upcoming screenings Video LUKE HALLS Lighting JANE COX Music JON HOPKINS Sound CHRISTOPHER SHUTT Great theatre needs great supporters Movement SIDI LARBI CHERKAOUI If you love NT Live, please support the National Theatre and Fights BRET YOUNT help us to continue to bring world-class theatre to cinemas. nationaltheatre.org.uk/support-the-NT Casting JULIA HORAN CDG Connect with us Subscribe to our email updates Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter ntlive.com/signup facebook.com/ntlive @ntlive Join in the conversation about tonight’s screening #HamletBarbican Upcoming broadcasts Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare a Bridge Theatre production In cinemas from March 22 HHHH ‘ Tremendously gripping. -

Critical Acclaim for the Seafarer

B e t w e e n T h e Between The Lines: Vol II Issue I 2008 Background on The Seafarer The Seafarer, like many of McPherson’s plays is set in In a candid interview with American Theatre Ireland, specifically in Baldoyle, a coastal town north Magazine, McPherson describes the moment of of Dublin. The play centers on Sharky, an alcoholic inspiration for The Seafarer: who returns home to care for his aging brother, Richard, who recently went blind. They are joined “The journey of The Seafarer was a long one for by Sharky’s friends Ivan and Nicky who are holed up me. There’s this monument in Ireland… a 5,000- in the basement of Richard’s home during a severe year-old tomb called Newgrange. It’s got a long storm. The friends’ poker game is interrupted by the tunnel with a little hole in the middle of it and arrival of a mysterious friend, Mr. Lockhart who raises on the winter solstice each year; the sun shines the stakes of the game damningly high. directly down that chamber and lights it up — on the darkest day of the year. That image was… so The Seafarer opened at the National Theatre in 2006 simple, spiritual, amazing. I wanted to write a play garnering the Olivier-Award for Best Play before that had that moment… that darkest moment, moving to Broadway in December 2007. One of the darkest day of the year, where at the end the most acclaimed plays of last season, the show ran a light comes in.” brief 133 performances at the Booth Theatre before becoming one of several casualties due to the stage- hands strike that closed nearly all Broadway shows for weeks. -

Drama & Theatre Studies Starter Pack

[Type here] King Edward VI College Drama & Theatre Studies Starter Pack [Type here] Welcome! Welcome to the drama department at King Edward’s! The aim of this booklet is to introduce you to some aspects of the course and to prepare you for studying with us at A level. You’ll find plenty of information about the course in the accompanying handbook and PowerPoint presentation but in this booklet I have put together some work for you to complete. Blue text contains a hyperlink. Just click to be transported to any online resource. Some of the activities are compulsory whilst others are designed to keep your mind stimulated over the coming weeks and months. It is important not to let your mind go stale. Success in drama requires a sharp analytical mind and a willingness to grapple with big ideas creatively. I wish you and yours the very best of health and I look forward to meeting you in September. In the meantime, join us on Twitter: @KingEds_Drama. We are always reflecting on our provision and practice. The information contained in this booklet is accurate as of April 2021 but we reserve the right to make alterations to reading lists, set texts and to the way in which we structure our course. A detailed course review takes place during May of every academic year. Shaun Passey, drama and theatre studies subject leader [email protected] [Type here] Compulsory Work Preparing for A level: speaking the same language You will be expected to use key terms when discussing your performance ideas, directing other students, and writing about work you have imagined, created or seen.