Katie Mitchell: Feminist Director As Pedagogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cole, E. K. (2015). the Method Behind the Madness: Katie Mitchell, Stanislavski, and the Classics. Classical Receptions Journal, 7(3), 400-421

Cole, E. K. (2015). The Method Behind the Madness: Katie Mitchell, Stanislavski, and the Classics. Classical Receptions Journal, 7(3), 400-421. https://doi.org/10.1093/crj/clu022 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1093/crj/clu022 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Oxford Journals at 10.1093/crj/clu022. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ The Method Behind the Madness: Katie Mitchell, Stanislavski, and the Classics Abstract Scholars frequently debate the applicability of contemporary theatre theories and acting techniques to Greek tragedy. Evidence both for and against such usage, however, is usually drawn from textual analyses which attempt to find support for these readings within the plays. Such arguments neglect the performative dimension of these theories. This article demonstrates an alternative approach by considering a case study of a Stanislavskian-inspired production of a Greek tragedy. Taking Katie Mitchell’s 2007 Royal National Theatre production Women of Troy as a paradigmatic example, the article explores the application of a Stanislavskian approach to Euripides’ Troades. I argue that Mitchell’s production indicates that modern theatre techniques can not only transform Greek tragedy into lucid productions of contemporary relevance, but can also supplement the scholarly analysis of the plays. -

Theatre Research International Women in Greek

Theatre Research International http://journals.cambridge.org/TRI Additional services for Theatre Research International: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Women in Greek Tragedy Today: A Reappraisal STEVE WILMER Theatre Research International / Volume 32 / Issue 02 / July 2007, pp 106 118 DOI: 10.1017/S0307883307002775, Published online: 15 June 2007 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0307883307002775 How to cite this article: STEVE WILMER (2007). Women in Greek Tragedy Today: A Reappraisal. Theatre Research International, 32, pp 106118 doi:10.1017/S0307883307002775 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TRI, IP address: 141.222.125.25 on 13 Feb 2013 theatre research international · vol. 32 | no. 2 | pp106–118 C International Federation for Theatre Research 2007 · Printed in the United Kingdom doi:10.1017/S0307883307002775 Women in Greek Tragedy Today: A Reappraisal steve wilmer Reacting to the concerns expressed by Sue-Ellen Case and others that Greek tragedies were written by men and for men in a patriarchal society, and that the plays are misogynistic and should be ignored by feminists, this article considers how female directors and writers have continued to exploit characters such as Antigone, Medea, Clytemnestra and Electra to make a powerful statement about contemporary society. In the 1970sand1980s feminist scholars launched an important critique of the patriarchal values embedded in Western culture. Amongst other targets, they questioned the canonization of ancient Greek tragedy, labelling the plays misogynistic.1 Nevertheless, many female directors and playwrights continue to stage ancient Greek tragedy today. -

The Thrill of Doing It Live’ Ledger, Adam

University of Birmingham ‘The thrill of doing it live’ Ledger, Adam Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Ledger, A 2017, ‘The thrill of doing it live’: devising and performing Katie Mitchell’s international multimedia productions. in K Reilly (ed.), Contemporary Approaches to Adaptation in Theatre. Adaptation in Theatre and Performance, Palgrave Macmillan. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 27/04/2017 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List Leonard Bernstein Candide Role: Candide Volkstheater Rostock: Director Johanna Schall, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2016 A Quiet Place Role: François Theater Lübeck: Director Effi Méndez, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2019 Ludwig van Beethoven Fidelio Role: Jaquino Nationaltheater Mannheim 2017: Director Roger Vontoble, Conductor Alexander Soddy Georges Bizet Carmen Role: Don José (English) Garden Opera: Director Saffron van Zwanenberg 2013/2014 OperaUpClose: Director Rodula Gaitanou, April-May 2012 Role: El Remendado Scottish Opera: Conductor David Parry, 2015 (cover) Melbourne City Opera: Director Blair Edgar, Conductor Erich Fackert May 2004 Role: Dancaïro Nationaltheater Mannheim: Director Jonah Kim, Conductor Mark Rohde, 2019/20 Le Docteur Miracle Role: Sylvio/Pasquin/Dr Miracle Pop-Up Opera: March/April 2014 Benjamin Britten Peter Grimes Role: Peter Grimes (cover) Nationaltheater Mannheim: Conductor Alexander Soddy, Director Markus Dietz 2019/20 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Role: Lysander (cover) Garsington Opera: Conductor Steauart Bedford, Director Daniel Slater June-July 2010 Francesco Cavalli La Calisto Role: Pane Royal Academy Opera: Dir. John Ramster, Cond. Anthony Legge, May 2008 Gaetano Donizetti Don Pasquale Role: Ernesto (English) English Touring Opera: Director William Oldroyd, Conductor Dominic Wheeler 2010 Lucia di Lammermoor Role: Normanno Nationaltheater Mannheim 2016 Jonathan Dove Swanhunter Role: Soppy Hat/Death’s Son Opera North: Director Hannah Mulder, Conductor Justin Doyle April -

The Inside Guide to Directing

THE INSIDE GUIDE TO DIRECTING Introduction by 02 Katy Rudd What is Directing? 06 Artist profile: 08 Ashen Gupta Pre-Rehearsals 12 Artist Profile: 16 GUIDE Ebenezer Bamgboye Guide compiled by Euan Borland Rehearsal Room 20 Directing Exercises by Roberta Zuric Photography Credits Artist Profile: 24 Joanna Higson Manuel Harlan Sean Linnen EDUCATION & COMMUNITY How to be a Leader 28 Director of Education & Community Hannah Fosker Education Manager Top Tips for Directing 30 Euan Borland Young Person’s Programme Manager Naomi McKenna Lawson Further Reading, 32 Education & Community Coordinator Kate Lawrence-Lunniss Watching & Listening Education & Community Intern Annys Whyatt Abena Obeng Glossary of Terms 34 With generous thanks to Old Vic staff and associates Next Steps 36 If you would like to learn more about our education programmes please contact [email protected] CONTENTS 1 When I left university, I knew that I wanted to During this time I had the good fortune to be a director but I had no idea how, or where, meet Marianne Elliott who kindly had a cup to start. At university I wrote and directed of tea with me – she gave me some advice plays as part of my course and I was given and told me to go to the regions and learn a good introduction to making theatre. your craft. Then she wished me good luck. In our spare time we put on our own shows rehearsing after hours in whatever space we So I did. I went to Salisbury Playhouse where could commandeer; empty lecture rooms, I spent three glorious months assisting on communal spaces or failing that our bedrooms. -

Directors Give Instructions

Directors give instructions On the publication of her book The Director’s Craft: A Handbook for the Theatre , Katie Mitchell discusses the inheritance of Stanislavski, working with multi-media, and why painstaking preparation is absolutely essential This event took place at Central School of Speech & Drama, University of London, on 14 October 2008 1 Guest speaker: Katie Mitchell (KM), director Chair: Prof Andy Lavender (AL), Dean of Research, Central School of Speech & Drama 1 This transcript of the conversation was edited by Joel Anderson, Andy Lavender [and Katie Mitchell]. The conversation was between Andy Lavender and Katie Mitchell, with audience questions at the end. 1 About Katie Mitchell: Katie in rehearsal for Euripides’ Women of Troy © Stephen Cummiskey, 2007 Controversial amongst critics, polarising amongst audiences, and highly respected amongst her peers, director Katie Mitchell produces work of extraordinary clarity and decidedness that has won her international acclaim. She began her career at London’s King’s Head before joining new-writing theatre Paines Plough, then moving to the RSC as assistant director. A devotee of the methods of Russian pedagog Konstantin Stanislavski, she travelled to Eastern Europe in 1989 to meet and study with proponents Lev Dodin of the St Petersburg Maly Teatr and Tadeusz Kantor, to explore his ingrained theatrical inheritance. 2 In the 1990s she set up theatre company Classics on a Shoe String, before rejoining the RSC in 1998 to run their black box project The Other Place, encouraging new initiatives in this now-retired experimental space. She has directed for the Welsh National Opera and been an associate of the Royal Court; she is currently Associate Director of the National Theatre. -

A Dream Play Background Pack

Education A Dream Play Background Pack Contents A Dream Play 2 Introduction 3 The Original Play 4 The Director: Interview with Katie Mitchell 5 The Actor: Interview with Angus Wright 9 The Designer: Interview with Vicki Mortimer 12 Activities and Discussion 15 Related Materials 16 ADreamPlay By August Strindberg in a new version by Caryl Churchill with additional material by Katie Mitchell and the Company Angus Wright Photo: Stephen Cummiskey A Dream Play Background pack written by NT Education Background pack By August Strindberg, in a Jonathan Croall, journalist National Theatre © Jonathan Croall new version by Caryl Churchill and theatrical biographer, and South Bank The views expressed in this With additional material by author of three books in the London SE1 9PX background pack are not Katie Mitchell and the series ‘The National Theatre T 020 7452 3388 necessarily those of the Company. at Work’. F 020 7452 3380 National Theatre Director Editor E educationenquiries@ Katie Mitchell Emma Thirlwell nationaltheatre.org.uk Further production details Design www.nationaltheatre.org.uk Patrick Eley, Lisa Johnson A Dream Play CAST (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) KATIE MITCHELL Director VICKI MORTIMER Designer MARK ARENDS CHRIS DAVEY Lighting Designer Young George, the broker’s brother KATE FLATT Choreographer Geoffrey, Victoria’s lover SIMON ALLEN Music Director and Arranger ANASTASIA HILLE CHRISTOPHER SHUTT Sound Designer Christine, the broker’s mother KATE GODFREY Company Voice Work KRISTIN HUTCHINSON Rachel, the broker’s first wife Music played live by: Paul Higgs Associate MD/piano/keyboard SEAN JACKSON Joe Townsend violin Security Supervisor Katja Mervola viola Port Health Officer Penny Bradshaw cello CHARLOTTE ROACH Schubert’s ‘Nacht und Träume’ specially Lina the maid recorded by: Ugly Edith, the broker’s co-respondent Mark Padmore tenor DOMINIC ROWAN Andrew West piano Herbert, the broker’s father Adult George, the broker’s brother This production opened at the National’s JUSTIN SALINGER Cottesloe Theatre on 15 February 2005. -

Willful Distraction: Katie Mitchell, Auteurism and the Canon Tom Cornford

Willful Distraction: Katie Mitchell, Auteurism and the Canon Tom Cornford Willfulness The opening of Katie Mitchell’s Royal Opera House production of Lucia di Lammermoor in April 2016 was, unusually, considered worthy of mention on the following morning’s Today programme. Widespread booing was reported and the Guardian critic Charlotte Higgins described ‘a real feeling of division in the audience’ over Mitchell and her designer Vicki Mortimer’s decision to use a form of split-screen staging to expose the operations and consequences of patriarchal abuse in the narrative that are otherwise excluded from the audience’s direct awareness by being conducted off-stage (BBC News, 2016). These interpolated scenes, which included the staging of Lucia’s murder of her husband, had been considered by the Royal Opera House’s management to be sufficiently concerning to warrant the sending of an email to those who had booked for the production, warning of ‘scenes that feature sexual acts portrayed on stage, and other scenes that – as you might expect from the story of Lucia – feature violence’. The Opera House sought to reassure its customers that ‘If there are any members of your party who you feel may be upset by such scenes then please email us […] and we will, of course, discuss suitable arrangements’ (Royal Opera House, 2016). Mitchell’s interpolations were widely criticised in reviews of the opera. ‘A lot of thought has gone into Katie Mitchell’s staging,’ wrote Rupert Christiansen (2016), ‘most of it misguided’. Mitchell has long had a reputation with British theatre critics for willfulness. In 2007, reviews of her production of Euripides’ Women of Troy at the National Theatre united voices from opposite sides of the political spectrum in approbation. -

Katie Mitchell's Iphigenia at Aulis and the Theatre of Sacrifice Kim Solga the University of Western Ontario

Western University Scholarship@Western Department of English Publications English Department 5-2008 Body Doubles, Babel's Voices: Katie Mitchell's Iphigenia at Aulis and the Theatre of Sacrifice Kim Solga The University of Western Ontario Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/englishpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Citation of this paper: Solga, Kim, "Body Doubles, Babel's Voices: Katie Mitchell's Iphigenia at Aulis and the Theatre of Sacrifice" (2008). Department of English Publications. 12. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/englishpub/12 1 Body Doubles, Babel’s Voices: Katie Mitchell’s Iphigenia at Aulis and the Theatre of Sacrifice [T]he symbol manifests itself first of all as the murder of the thing.1 1. Body doubles 16 July 2004: I’m a sweaty bundle of jitters in the back of the National Theatre’s Lyttleton auditorium, shifting from side to side in my seat. On stage, Hattie Morahan and Kate Duchêne, playing Iphigenia and Clytemnestra in Katie Mitchell’s production of Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis, collapse into one another, a messy tangle of clutching limbs. Iphigenia has just pleaded with her father Agamemnon (Ben Daniels) for her life, but to no avail. She knows now that she must be murdered so that his fleet may make fast for Troy, setting in motion a chain of events that will lead to the staging of one of ancient Greece’s foundation myths of democratic civilization. And yet for Mitchell this is not a moment of grandiose gesture or carefully coded sorrow: Morahan and Duchêne are overwhelmed by their emotions in a manner that is rarely seen in British (or North American) stage realism. -

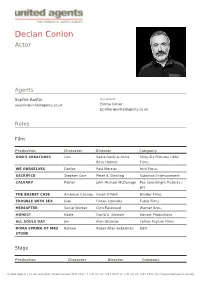

Declan Conlon Actor

Declan Conlon Actor Agents Sophie Austin Assistant [email protected] Emma Collier [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company GOD'S CREATURES Con Saela Davis & Anna Sixty-Six Pictures / BBC Rose Holmer Films WE OURSELVES Declan Paul Mercier Irish Focus SACRIFICE Stephen Gair Peter A. Dowling Subotica Entertainment CALVARY Father John Michael McDonagh Fox Searchlight Pictures / BFI THE BASKET CASE Ambrose Cassidy Owen O'Neill Blinder Films TROUBLE WITH SEX Ivan Fintan Connolly Fubar Films HEREAFTER Social Worker Clint Eastwood Warner Bros. HONEST Eddie David A. Stewart Honest Productions ALL SOULS DAY Jim Alan Gilsenan Yellow Asylum Films ROMA SPRING OF MRS Romeo Rober Allan Ackerman HBO STONE Stage Production Character Director Company United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] MY EYES WENT DARK Nikolai Koslov Matthew Wilkinson 107Group / Traverse Theatre THE FALL OF THE SECOND Tom Carney / Billy Annie Ryan Corn Exchange / Abbey REPUBLIC Kinlan T.D. Theatre THE FERRYMAN Muldoon Sam Mendes Gielgud Theatre ANNA KARENINA Karenin Wayne Jordan Abbey Theatre QUIETLY Ian Jimmy Fay Irish Repertory Theatre / Abbey Theatre JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK Captain Boyle Mark O'Rowe Gate Theatre Dublin THE GIGLI CONCERT JPW King David Grindley Gate Theatre Dublin DANCING AT LUGHNASA Father Jack Annabelle Comyn Lyric Theatre Belfast HEDDA GABLER Judge Brack Annabelle Comyn Abbey Theatre A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S Theseus / Oberon Gavin -

Penelope Mcghie Photo: Ric Bacon

59 St. Martin's Lane London WC2N 4JS Phone: 0207 836 7849 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nikiwinterson.com Penelope McGhie Photo: Ric Bacon Height: 5'10" (177cm) Eye Colour: Grey-Green Weight: 10st. 4lb. (65kg) Hair Colour: Dark Brown Playing Age: 50 - 60 years Hair Length: Mid Length Appearance: White Voice Character: Assured Other: Equity Voice Quality: Clear Film Film, Beth, The Selfish Act of Community, Andrew Bonacina & Victoria Brooks, Jesse Jones Feature Film, DeathEater, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2, Warner Bros, David Yates Feature Film, Death Eater, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1, Warner Bros, David Yates Feature Film, Margaret, Elizabeth -The Golden Age, Working Title / Universal, Shekhar Kapur Film, Woman in Street, The Shell Seekers, Gate Television Productions, Piers Haggard Stage Stage, Ensemble, u/s Pernelle, Tartuffe, National Theatre, Blanche McIntyre Stage, Party Guest u/s Gertrude/Player Queen, Hamlet, Almeida West End, Robert Icke Stage, Ensemble, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime, National Theatre at The Gielgud, Marianne Elliot Stage, Ensemble, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime, National Theatre at the Gielgud, Marianne Elliott Stage, Ensemble, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime, National Theatre at The Gielgud, Marianne Elliott Stage, Mother of the Bride, I Do, Hilton Docklands, Almeida Theatre/Dante or Die, Daphna Attias Stage, Mother of the Bride, I Do, Hilton Islington, Almeida Festival / Dante or Die, Daphna Attias Stage, Woman, City Stories, St James Theatre, James Phillips Stage, Elka, Mare Rider, Arcola Theatre /Europe Now Festival, Amsterdam, Mehmet Ergen Stage, Lorna, Still I Pray (Barbican/OSBTTA Finals), Building Site, St Bartholomew the Great's Church, Anouke Brook Stage, Beth, The Selfish Act of Community, Whitstable Biennale 2012, Jesse Jones Stage, Flora, Autobiographer, Toynbee Studios, London.