An Inquiry Into Media Access to Police Radio Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCANNER DIGEST NEWSLETTER – ISSUE 69 PAGE 1 Opened a New Niche in the Hobby As Enthusiasts Would Search for Hours Under Covering New Frequencies

I don’t remember if Radio Shack continued with the Radio! Magazine. The little search over the web yielded no hits. ISSUE 69 JUL-AUG-SEPT 2014 Alan Cohen ♦ Transformation in the Radio Scanning Hobby - Part 2 PUBLISHER Lou Campagna ♦ Eastern PA - Manhunt for Cop [email protected] Killer in Pocono Mountains Transformation in the Radio ♦ Washington DC Update Scanning Hobby - Part 2 ♦ Western PA Update Crystal Controlled to Frequency ♦ Akihabara Radio Center Japan Synthesized – Part 3 By Lou Campagna st ♦ Memory Lane - Radio Shack’s 1 A frequency synthesizer is an electronic system for generating any of a range of frequencies as in a radio or Scanner Magazine receiver (scanner). This was probably the greatest improvement in the scanning hobby. No longer were you limited to the number of frequencies to monitor. Crystal- GENERAL EDITOR Alan Cohen controlled scanners were limited by channel capacity. [email protected] Investing in crystals also became pretty expensive too! While scouring through I remember I had inquired about the various police and fire the magazine bin frequency crystals that were available for me to monitor during a recent such radio communications in my area. hamfest, I came across a magazine produced As a teenager, I was working odd jobs so that I can drop by Radio Shack dated $5 each for a crystal. The cost of crystals limited me to Spring 1994. My cost what I could listen to, so extreme care in purchasing each only 25¢. Wow, twenty crystal. Mainly police and fire crystals were purchased to years ago, boy how fill the needs of a limited capacity scanner radio. -

Scanner Digest Newsletter – Issue 71 Page 1

ISSUE 71 JAN-FEB-MAR 2015 ♦ SWLFEST 2015 WRAP UP ♦ A GUIDE TO PUBLIC SAFETY SCANNING – Part 2 - VENTURA COUNTY CA by Larry Smith ♦ SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY – MONMOUTH CO. SHERIFF UPDATE ♦ ANNUAL MILITARY AIR SHOW REVIEW & PREVIEW by Dan Myers Richard Cuff & John Figliozzi. ♦ FEDERAL COLUMN by Mark Meece The Winter SWL Fest is a conference of radio hobbyists of ♦ AMATEUR RADIO PROPAGATION all stripes, from DC to daylight. Every year scores of BANNERS Part 1 by Robert Gulley AK3Q hobbyists descend on the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania suburbs for a weekend of camaraderie. The Fest is ♦ NEW HAMPSHIRE by John Buldoc sponsored by NASWA, the North American Shortwave Association, but it covers much more than just shortwave; ♦ PRODUCT ANNOUNCEMENT – mediumwave (AM), scanning, satellite TV, and pirate Dxtreme Station Log, Version 11.0 broadcasting are among the other topics that the Fest covers. Whether you’ve been to every Fest (all 26, starting ♦ CANADA UPDATE – John Leonardelli with the first year at the fabled Pink & Purple Room of the Fiesta Motor Inn) or this year’s will be your first, you’re sure to find a welcome from your fellow hobbyists. GENERAL EDITOR Alan Cohen [email protected] History of the Winter SWL Festival It was in February 1988 that a group of 40 DXers assembled at the Fiesta Motor Inn in Willow Grove, PA to Another year has passed and once again SWL “just talk radio.” The first Fest was held in the “beautiful enthusiasts gathered from around the world to attend the pink and purple Pancho Villa Room” at the Fiesta and Annual SWL WinterFest 2015 held in Plymouth Meeting featured a blizzard and a shooting in the motel restaurant PA (not a participant!). -

Desktop Radio Scanner

20-405 / PRO-405 User’s Guide Desktop Radio Scanner Thank you for purchasing your Desktop Radio Scanner from RadioShack. Please read this user’s guide before installing, setting up, and using your new scanner Contents Package Contents ..............................................................................................4 Contents Features ..............................................................................................................4 Understanding Your Scanner ......................................................................................... 6 Channel Storage Banks ............................................................................................. 6 Service Banks ............................................................................................................ 6 Preprogrammed Service Bank Frequencies .................................................................. 7 Marine ....................................................................................................................... 7 Fire/Police ................................................................................................................. 8 Aircraft ...................................................................................................................... 9 Ham Amateur Radio .................................................................................................. 9 FM Broadcast ............................................................................................................ 9 -

A Survey on Legacy and Emerging Technologies for Public Safety Communications

1 A Survey on Legacy and Emerging Technologies for Public Safety Communications Abhaykumar Kumbhar1;2, Farshad Koohifar1, Ismail˙ Guvenc¸¨ 1, and Bruce Mueller2 1Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33174 2Motorola Solutions, Inc., Plantation, FL 33322 USA Email: fakumb004, fkooh001, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Effective emergency and natural disaster manage- policy have been discussed in [4] and [5], which study the ment depend on the efficient mission-critical voice and data decoupling of spectrum licenses for spectrum access, a new communication between first responders and victims. Land nationwide system built on open standards with consistent Mobile Radio System (LMRS) is a legacy narrowband technology used for critical voice communications with limited use for data architecture, and fund raising approach for the transition to a applications. Recently Long Term Evolution (LTE) emerged as new nationwide system. As explained in [6], communication of a broadband communication technology that has a potential time critical information is an important factor for emergency to transform the capabilities of public safety technologies by response. In [7] and [8], insights on cognitive radio technology providing broadband, ubiquitous, and mission-critical voice and are presented, which plays a significant role in making the best data support. For example, in the United States, FirstNet is building a nationwide coast-to-coast public safety network based use of scarce spectrum in public safety scenarios. Integration of LTE broadband technology. This paper presents a comparative of other wireless technologies into PSC is studied in [9], with survey of legacy and the LTE-based public safety networks, and a goal to provide faster and reliable communication capability discusses the LMRS-LTE convergence as well as mission-critical in a challenging environment where infrastructure is impacted push-to-talk over LTE. -

Monitoring Times 2000 INDEX

Monitoring Times 1994 INDEX FEATURES: Air Show: Triumph to Tragedy Season Aug JUNE Duopolies and DXing Broadcast: Atlantic City Aero Monitoring May JULY TROPO Brings in TV & FM A Journey to Morocco May Dayton's Aviation Extravaganza DX Bolivia: Radio Under the Gun June June AUG Low Power TV Stations Broadcasting Battlefield, Colombia Flight Test Communications Jan SEP WOW, Omaha Dec Gathering Comm Intelligence OCT Winterizing Chile: Land of Crazy Geography June NOV Notch filters for good DX April Military Low Band Sep DEC Shopping for DX Receiver Deutsche Welle Aug Monitoring Space Shuttle Comms European DX Council Meeting Mar ANTENNA TOPICS Aug Monitoring the Prez July JAN The Earth’s Effects on First Year Radio Listener May Radio Shows its True Colors Aug Antenna Performance Flavoradio - good emergency radio Nov Scanning the Big Railroads April FEB The Half-Rhombic FM SubCarriers Sep Scanning Garden State Pkwy,NJ MAR Radio Noise—Debunking KNLS Celebrates 10 Years Dec Feb AntennaResonance and Making No Satellite or Cable Needed July Scanner Strategies Feb the Real McCoy Radio Canada International April Scanner Tips & Techniques Dec APRIL More Effects of the Earth on Radio Democracy Sep Spy Catchers: The FBI Jan Antenna Radio France Int'l/ALLISS Ant Topgun - Navy's Fighter School Performance Nov Mar MAY The T2FD Antenna Radio Gambia May Tuning In to a US Customs Chase JUNE Antenna Baluns Radio Nacional do Brasil Feb Nov JULY The VHF/UHF Beam Radio UNTAC - Cambodia Oct Video Scanning Aug Traveler's Beam Restructuring the VOA Sep Waiting -

SDR Forum Technical Conference 2007 Proceeding of the SDR 07 Technical Conference and Product Exposition

Copyright Transfer Agreement: The following Copyright Transfer Agreement must be included on the cover sheet for the paper (either email or fax)—not on the paper itself. “The authors represent that the work is original and they are the author or authors of the work, except for material quoted and referenced as text passages. Authors acknowledge that they are willing to transfer the copyright of the abstract and the completed paper to the SDR Forum for purposes of publication in the SDR Forum Conference Proceedings, on associated CD ROMS, on SDR Forum Web pages, and compilations and derivative works related to this conference, should the paper be accepted for the conference. Authors are permitted to reproduce their work, and to reuse material in whole or in part from their work; for derivative works, however, such authors may not grant third party requests for reprints or republishing.” Government employees whose work is not subject to copyright should so certify. For work performed under a U.S. Government contract, the U.S. Government has royalty-free permission to reproduce the author's work for official U.S. Government purposes. SDR Forum Technical Conference 2007 Proceeding of the SDR 07 Technical Conference and Product Exposition. Copyright © 2007 SDR Forum. All Rights Reserved ALL DIGITAL FPGA BASED FM RADIO RECEIVER Chen Zhang, Christopher R. Anderson, Peter M. Athanas The Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) Blacksburg, VA, USA 24061. Email: {zhangc, chris.anderson, athanas}@vt.edu ABSTRACT purpose. In this work, filtering, mixing and demodulating, the major tasks of the receiver are perfectly done digitally in This paper presents the design and implementation of the FPGA and can be reconfigured in real-time by PC. -

Selection and Operation of Wireless Microphone Systems (English)

SELECTION AND OPERATION WIRELESS MICROPHONE SYSTEMS Updated for digital wireless By Tim Vear A Shure Educational Publication SELECTION AND OPERATION WIRELESS MICROPHONE SYSTEMS Updated for digital wireless By Tim Vear Selection and Operation of Table of Contents WIRELESS Microphone Systems Introduction ........................................................................ 4 Other Radio Services .................................................. 34 Non-Broadcast Sources .............................................. 34 Part One Range of Wireless Microphone Systems ..................... 35 Wireless Microphone Systems: How They Work Spread Spectrum Transmission .................................. 35 Digital Wireless Systems ............................................. 36 Chapter 1 Operation of Wireless Systems Outside of the U.S. ..... 39 Basic Radio Principles ....................................................... 5 Radio Wave Transmission ........................................... 5 Part Two Radio Wave Modulation .............................................. 7 Wireless Microphone Systems: How To Make Them Work Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Basic Radio Systems ......................................................... 8 Wireless System Selection and Setup ............................... 40 System Description ..................................................... 8 System Selection ......................................................... 40 Input Sources ............................................................. 8 Crystal Controlled vs. Frequency -

Ws1065 Table of Contents

DIGITAL TRUNKING Desktop/Mobile Radio Scanner OWNER’S MANUAL WS1065 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Introduction ................................................... 4 What is Object Oriented Scanning? ............................. 4 Package Contents ...................................................... 5 Scanning Legally ......................................................... 5 Features ...................................................................... 6 Setup ............................................................. 7 Antenna ...................................................................... 7 External Antenna ........................................................ 8 Desktop Operation ..................................................... 9 Mount Installation ....................................................... 9 Headphones and Speakers ....................................... 10 Listening Safely ......................................................... 10 AC Adapter ............................................................ 11 DC Power Cable ....................................................... 12 Understanding the Keypad ...................................... 13 Turning on the Scanner ............................................ 15 Understanding the Display Icons ............................. 16 Programming .............................................. 17 Programming Cables ................................................ 17 RadioReference.com ................................... 18 Scanner Cloning ...................................................... -

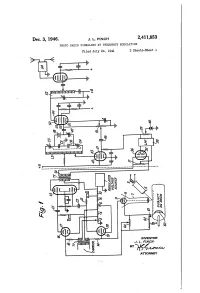

US2411853.Pdf

Patented 'Dec. 3, 1946 ' 2,411,853 _ UNITED STATE 3 PATENT orifice; ~; PHOTO RADIO SIGNALING BY‘FREQUENCY -' MODULATION 1 - > ~ James L. Finch, East Rockaway; N. Y, assignor'i to Radio Corporation of America, a. corpora tion of Delaware VApplication July 24, 1941, Serial No. 403,821 - 11 Claims. (01. 178-6) v. _ 1 I propose .to transmit during this period a selected. This application discloses a new and improved frequency ‘corresponding .to some de?nite pic-1 method of and means for transmission and re ture ‘shade, preferably black or white or some ception of photo radio subject matter by modu de?nite frequency which would be called super lating the frequency of a carrier wave in direct black or super-white. " . ' y ' proportion to the density or shading of the photo - In describing my invention in detail reference radio subject matter being scanned, transmitting will be made to the attached drawings'wherein the same and receiving the same. Figure '1 illustrates somewhat diagrammatically, J vIn k'novvn'systemslof photo radio transmission the essential elements, of a transmitter arranged of-the type described above any variation in the 10 in accordance with my invention; Figure 2 illus frequency adjustment of the transmitter circuits trates a receiver arranged in accordance with my may result in an error in the received photo'- radio invention to receive the transmission from the matter. Should the receiver adjustment drift, transmitter ‘of Figure land to be controlled .by then the picture may appear darker or lighter the said de?nite frequency transmitted at the on the average than the original. -

Ez Scan Digital Handheld Radio Scanner

TRX-1 User Guide EZ SCAN DIGITAL HANDHELD RADIO SCANNER All Hazards NOAA’s National Weather Service ® Contents Introduction......................................................................4 What is Object Oriented Scanning?...............................4 Features............................................................................5 Package Contents............................................................5 Scanning Legally...............................................................6 FCC Statement.................................................................7 Setup.................................................................................8 Antenna............................................................................8 Headphones and Speakers.............................................9 Batteries..........................................................................10 External Power................................................................11 Swivel Belt Clip................................................................11 Understanding the Keypad...........................................12 Turning On and Set Squelch........................................13 Set Bandplan and Clock...............................................14 Program Methods..........................................................15 Setting Location.............................................................16 Power Up Password........................................................18 Understanding the Display............................................18 -

A Look at Project 25 (P25) Digital Radio Aaron Rossetto Principal Architect, NI Agenda

A Look at Project 25 (P25) Digital Radio Aaron Rossetto Principal Architect, NI Agenda • What is Project 25? • A brief introduction to trunked radio • The P25 protocol • GNU Radio and P25 decoding experiments About the presenter • 21-year veteran of NI* • August 2019: Joined SDR team to work on UHD 4.0 and RFNoC • Long-time SDR enthusiast • 2003: Ten-Tec RX320D • FunCube, AirSpy, RTL-SDR dongles • Long-time interest in public safety communications monitoring • 1988: PRO-2013 (my first scanner!) • 1997-present: Various Uniden scanners * NOTE: Not speaking for my employer in this presentation What is Project 25? • In an emergency, communication is often the key to survival • Many agencies must collaborate and coordinate in a disaster scenario • First responders: Police, fire, EMS (city, county, state) • Federal agencies (e.g. FEMA, military reserves, NTSB, ATF, etc.) • Relief agencies, local government resources, etc. • Challenge: Lack of interoperability between public safety comms systems • Technical: Spectrum used, system features • Political: Isolated or lack of planning, lack of coordination, funding disparities, jurisdictional issues, etc. What is Project 25? • 1988: U.S. Congress directs the Federal Communications Commission to study recommendations for improving existing public safety communications systems • 1989: APCO Project 25 coalition formed • Association of Public Safety Communications Officials (APCO) • National Association of State Telecommunications Directors (NASTD) • National Telecommunications and Information Administration -

10Step Guide

SMART CHOICE! SERIES 10 step guide to choosing the right MOBILE RADIO Choosing the proper radio affects: • The safety of your staff • Your team’s effectiveness • Profitability That’s why Icom makes a wide range of radios. Use this guide to help choose the features you need while remaining affordable and cost-effective. Let’s get started! RADIOS FOR PEOPLE WHO MAKE SMART CHOICES STEP 1: FORM FACTOR Chassis Size The internal frame of the radio could Varies from large to compact. Some be metal or plastic. Plastic retains mobile radios have removable displays heat, and heat kills electronics. Metal for remote mounting of the body under is an efficient “heat sink”, meaning the seat or in the trunk to preserve it helps dissipate heat quickly. Metal space in the cockpit. also provides a good ground plane for optimum performance. Separate Volume knob sections within the chassis shield the Allows for adjusting the volume transmitter and receiver sections. From without looking. Up-down volume most basic to most advanced, every buttons require looking at the radio. Icom radio features a one-piece, die- cast aluminum chassis for strength, Rotary channel knob durability, and performance. Selects an operating channel that has been pre-programmed to a Case specific frequency by your dealer. The outer shells are usually various Similar to a TV channel selector. grades of high impact plastic materials. A bumper at the lower and upper Rough use requires the best materials for limits and individual detents (clicks) long life. Military-tough polycarbonate in-between provide tactical feed- shells protect every current Icom radio back during channel changes.