Toby F. Martin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Planning Regulatory Committee

Planning Regulatory Committee Date: Friday, 22 May 2009 Time: 10.00am Venue: Edwards Room, County Hall, Norwich Persons attending the meeting are requested to turn off mobile phones. Membership Mr C Armes Mr P Hacon Mr D Baxter Mr D Harrison Dr A Boswell Mr C Joyce Mr D Callaby Mrs T Paines Mr S Dorrington Mr J Rogers Mrs J Eells Mr J Shrimplin Mrs I Floering Blackman Mr M Wright Mr A Gunson For further details and general enquiries about this Agenda please contact the Committee Officer: Lesley Rudelhoff Scott on 01603 222963 or email [email protected] Where the County Council have received letters of objection in respect of any application, these are summarised in the report. If you wish to read them in full, Members can do so either at the meeting itself or beforehand in the Department of Planning and Transportation on the 3rd Floor, County Hall, Martineau Lane, Norwich. Planning Regulatory Committee 22 May 2009 A g e n d a 1. To receive apologies and details of any substitute members attending. 2. Minutes: To receive the Minutes of the last meeting held on 24 (Page 1) April 2009 3. Members to Declare any Interests Please indicate whether the interest is a personal one only or one which is prejudicial. A declaration of a personal interest should indicate the nature of the interest and the agenda item to which it relates. In the case of a personal interest, the member may speak and vote on the matter. Please note that if you are exempt from declaring a personal interest because it arises solely from your position on a body to which you were nominated by the County Council or a body exercising functions of a public nature (e.g. -

Letter and List of Consultees

Children's Services County Hall Martineau Lane Norwich NR1 2DL NCC contact number: 0344 800 8020 To: Statutory Consultees Textphone: 0344 800 8011 Your Ref: My Ref: JBi01 Date: 2 February 2015 Tel No.: 01603 223905 Email: [email protected] Statutory consultation on a proposal to amalgamate Mileham Primary School and Litcham School into a single all-through school for pupils aged 4 – 16 from September 2015. Please find enclosed a copy of the consultation document relating to the proposal to amalgamate Mileham Primary School and Litcham School from 1 September 2015. In order to legally combine two schools into a single organisation, the Local Authority has to publish a formal proposal to ‘close’ Mileham Primary School on 31 August 2015. Under Section 16(1) of the Education and Inspections Act 2006, the Local Authority as proposer of the closure of a rural primary school must consult: Parents of pupils at the school The local district or parish council where the school is situated In addition the document is provided to people and organisations that may have an interest in this proposal including: The governing body of the school Pupils at the school All staff at the school The governing bodies, teachers and other staff of any other school that might be affected Diocesan Boards of Education Parents of any pupils at other schools who may be affected by the proposal Trade unions who represent staff at the school Local County Councillors and MPs This document is issued to you as outlined above and I should be grateful if you would share the information widely so all those who would like to comment, have an opportunity to do so. -

Breckland Definitive Statement of Public Rights Of

Norfolk County Council Definitive Statement of Public Rights of Way District of Breckland Contains public sector information c Norfolk County Council; Available for re-use under the Open Government Licence v3: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/ Statement downloaded 16th January 2021; latest version available online at: https://www.norfolk.gov.uk/out-and-about-in-norfolk/public-rights-of-way/ map-and-statement-of-public-rights-of-way-in-norfolk/definitive-statements Document compiled by Robert Whittaker; http://robert.mathmos.net/ PARISH OF ASHILL Footpath No. 1 (South Pickenham/Watton Road to Houghton Common Road). Starts from fieldgate on South Pickenham/Watton Road and runs eastwards to enter Houghton Common Road opposite western end of Footpath No. 5. Bridleway No. 2 (South Pickenham/Watton Road to Peddars Way). Starts from South Pickenham/Watton Road and runs south westwards and enters Peddars Way by Caudle Hill. Footpath No 5 (Houghton Common to Church Farm) Starts from Houghton Common Road opposite the eastern end of Footpath No. 1 and runs eastwards to TF 880046. From this point onwards the width of the path is 1.5 metres and runs north along the eastern side of a drainage ditch for approximately 94 metres to TF 879047 where it turns to run in an easterly direction along the southern side of a drainage ditch for approximately 275 metres to TF 882048. The path then turns south running on the western side of a drainage ditch for approximately 116 metres to TF 882046, then turns eastwards to the south of a drainage ditch for approximately 50 metres to TF 883047 where it turns to run southwards on the western side of a drainage ditch for approximately 215 metres to TF 883044 thereafter turning west along the northern side of a drainage ditch and hedge for approximately 120 metres to TF 882044. -

Breckland District Council (Ashill

PARISH OF ASHILL Footpath No. 1 (South Pickenham/Watton Road to Houghton Common Road). Starts from fieldgate on South Pickenham/Watton Road and runs eastwards to enter Houghton Common Road opposite western end of Footpath No. 5. Bridleway No. 2 (South Pickenham/Watton Road to Peddars Way). Starts from South Pickenham/Watton Road and runs south westwards and enters Peddars Way by Caudle Hill. Footpath No 5 (Houghton Common to Church Farm) Starts from Houghton Common Road opposite the eastern end of Footpath No. 1 and runs eastwards to TF 880046. From this point onwards the width of the path is 1.5 metres and runs north along the eastern side of a drainage ditch for approximately 94 metres to TF 879047 where it turns to run in an easterly direction along the southern side of a drainage ditch for approximately 275 metres to TF 882048. The path then turns south running on the western side of a drainage ditch for approximately 116 metres to TF 882046, then turns eastwards to the south of a drainage ditch for approximately 50 metres to TF 883047 where it turns to run southwards on the western side of a drainage ditch for approximately 215 metres to TF 883044 thereafter turning west along the northern side of a drainage ditch and hedge for approximately 120 metres to TF 882044. The width of the path from this point is not determined as the path turns southwards to Church Farm. April 2004 Footpath No. 6 (Watton/Ashill Road to Footpath No. 5) Starts from Watton/Ashill Road north of Crown Inn and opposite Goose Green and runs westwards to TF 885046. -

Bedfordshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2004 Post-determination & Non-planning Eastern Region Bedfordshire 3 /227 (E.09.V009) TL 26964768 SG8 0ER INSTITUTE OF LEGAL EXECUTIVES, KEMPSTON MANOR Institute of Legal Executives, Kempston Manor, Manor Drive, Kempston, Bedfordshire Pixley, J & Lee, A Bedford : Albion Archaeology, 2004, 20pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Albion Archaeology Archaeological monitoring was carried out on groundworks at the site. Deep overburden deposits were observed. [Au(abr)] Bedford 3 /228 (E.09.V012) TL 21025513 PE19 6XE A421 GREAT BARFORD BYPASS A421 Great Barford Bypass, Anglian Watermain Diversion, Water End, Bedfordshire Maull, A Northampton : Northamptonshire Archaeology, 2005, 18pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Northamptonshire Archaeology An archaeological watching brief was carried out on topsoil stripping for a rerouted water pipeline. A settlement boundary ditch dating to the Late Iron Age/Roman period was recorded. Medieval/post- medieval furrows, field boundaries and ditches were also observed. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: LIA, MD, PM, RO, MD, PM 3 /229 (E.09.V008) TL 08885285 MK41 0NQ CHURCH OF ALL SAINTS, RENHOLD Church of All Saints, Renhold, Bedfordshire Albion Archaeology Bedford : Albion Archaeology, 2004, 5pp, pls, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: Albion Archaeology Archaeological monitoring was carried out on groundworks within the churchyard. The foundation raft for the tower was recorded. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: MD 3 /230 (E.09.V006) SP 95045674 MK43 7DL HARROLD LOWER SCHOOL Harrold Lower School, Library Extension, the Green, Harrold, Bedfordshire Thatcher, C & Abrams, J Bedford : Albion Archaeology, 2004, 13pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Albion Archaeology Monitoring was carried out on groundworks at the site. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION Breckland Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below Number of Number of Parish Parish Parishes Parishes Councillors to Councillors to be elected be elected Parish of Ashill Nine (9) Parish of Little Dunham Seven (7) Parish of Banham Nine (9) Parish of Little Ellingham Five (5) Parish of Bawdeswell Seven (7) Parish of Longham Seven (7) Parish of Beachamwell Seven (7) Parish of Lyng Seven (7) Parish of Beeston with Bittering Seven (7) Parish of Mattishall Nine (9) Parish of Beetley Seven (7) Parish of Merton Five (5) Parish of Besthorpe Seven (7) Parish of Mileham Seven (7) Parish of Billingford Seven (7) Parish of Mundford Nine (9) Parish of Bintree Seven (7) Parish of Narborough Seven (7) Parish of Blo` Norton Five (5) Parish of New Buckenham Seven (7) Parish of Bradenham Seven (7) Parish of Necton Nine (9) Parish of Brettenham and Seven (7) Parish of North Elmham Eleven(11) Kilverstone Parish of Bridgham Five (5) Parish of North Lopham Seven (7) Parish of Brisley Seven (7) Parish of North Pickenham Seven (7) Parish of Carbrooke Nine (9) Parish of North Tuddenham Seven (7) Parish of Caston Seven (7) Parish of Old Buckenham Eleven(11) Parish of Cockley Cley Five (5) Parish of Ovington Five (5) Parish of Colkirk Seven (7) Parish of Oxborough Five (5) Parish of Cranworth Seven (7) Parish of Quidenham Seven (7) Parish of Croxton Five (5) Parish of Rocklands Seven (7) Parish of East Tuddenham Seven (7) Parish of Rougham Seven (7) Parish of Elsing Seven (7) Parish of Roudham and Larling Seven (7) Parish -

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

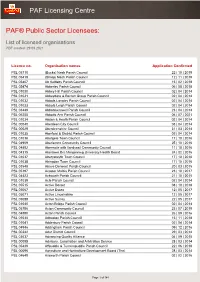

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

Minutes 28.9.15 1 DRAFT MINUTES of the MEETING OF

DRAFT MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF RUSHBROOKE WITH ROUGHAM PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY 28 SEPTEMBER 2015 Present: Cllrs I Steel (Chair), P Langdon, C Old, J Ottley, A Poole and F Shaw In attendance: 2 Members of the Public ACTION 15/045 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE: Cllrs M Chapple, M Cocksedge, C Drewienkiewicz, J Eden, Co Cllr T Clements and Borough Cllr S Mildmay-White 15/046 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST: None 15/047 APPROVAL OF MINUTES: The Minutes of the last PC Meeting held on 20 July 2015 were approved and signed. 15/048 MATTERS ARISING: None 15/049 PUBLIC FORUM: Two residents from Priors Close were present to ask as to progress re the felling of the Crab Apple Trees in the Close. This was discussed and some documentation passed to the Clerk for reference purposes. See Min 15/050 below for details. 15/050 POLICE REPORT: Thank you to those who came out in the pouring rain to attend the Rural North neighbourhood Watch and crime Reduction Roadshow last Wednesday evening it was lovely to meet you. If you require any more information, please do not hesitate to contact us. Below is a brief crime update for your information – Theft Barrow – Nostreetname – Between 1pm 11/09/15 to 1.30pm 18/09/15 A former church pew situated at the front of a property has been taken – Crime number BR/15/841 Burglaries Fornham St Martin – Gleneagles Close – Between 8.30am to 5.15pm 17/09/15 dwelling was entered via back wooden door being forced search made of all rooms and strewn belongings around then sprayed cleaning product over the computer – Crime number BR/15/835 -

Electoral Changes) Order 2002

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2002 No. 3221 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Breckland (Electoral Changes) Order 2002 Made - - - - - 18th December 2002 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) a report dated July 2002 on its review of the district of Breckland together with its recommendations: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give eVect to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Breckland (Electoral Changes) Order 2002. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “district” means the district of Breckland; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map marked “Map referred to in the District of Breckland (Electoral Changes) Order 2002”, of which prints are available for inspection at— (a) the principal oYce of the Electoral Commission; and (b) the oYces of Breckland District Council; (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.