Rule-Based Analysis of Dimensional Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administering Unidata on UNIX Platforms

C:\Program Files\Adobe\FrameMaker8\UniData 7.2\7.2rebranded\ADMINUNIX\ADMINUNIXTITLE.fm March 5, 2010 1:34 pm Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta UniData Administering UniData on UNIX Platforms UDT-720-ADMU-1 C:\Program Files\Adobe\FrameMaker8\UniData 7.2\7.2rebranded\ADMINUNIX\ADMINUNIXTITLE.fm March 5, 2010 1:34 pm Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Notices Edition Publication date: July, 2008 Book number: UDT-720-ADMU-1 Product version: UniData 7.2 Copyright © Rocket Software, Inc. 1988-2010. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks The following trademarks appear in this publication: Trademark Trademark Owner Rocket Software™ Rocket Software, Inc. Dynamic Connect® Rocket Software, Inc. RedBack® Rocket Software, Inc. SystemBuilder™ Rocket Software, Inc. UniData® Rocket Software, Inc. UniVerse™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2.NET™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2 Web Development Environment™ Rocket Software, Inc. wIntegrate® Rocket Software, Inc. Microsoft® .NET Microsoft Corporation Microsoft® Office Excel®, Outlook®, Word Microsoft Corporation Windows® Microsoft Corporation Windows® 7 Microsoft Corporation Windows Vista® Microsoft Corporation Java™ and all Java-based trademarks and logos Sun Microsystems, Inc. UNIX® X/Open Company Limited ii SB/XA Getting Started The above trademarks are property of the specified companies in the United States, other countries, or both. All other products or services mentioned in this document may be covered by the trademarks, service marks, or product names as designated by the companies who own or market them. License agreement This software and the associated documentation are proprietary and confidential to Rocket Software, Inc., are furnished under license, and may be used and copied only in accordance with the terms of such license and with the inclusion of the copyright notice. -

Types and Programming Languages by Benjamin C

< Free Open Study > . .Types and Programming Languages by Benjamin C. Pierce ISBN:0262162091 The MIT Press © 2002 (623 pages) This thorough type-systems reference examines theory, pragmatics, implementation, and more Table of Contents Types and Programming Languages Preface Chapter 1 - Introduction Chapter 2 - Mathematical Preliminaries Part I - Untyped Systems Chapter 3 - Untyped Arithmetic Expressions Chapter 4 - An ML Implementation of Arithmetic Expressions Chapter 5 - The Untyped Lambda-Calculus Chapter 6 - Nameless Representation of Terms Chapter 7 - An ML Implementation of the Lambda-Calculus Part II - Simple Types Chapter 8 - Typed Arithmetic Expressions Chapter 9 - Simply Typed Lambda-Calculus Chapter 10 - An ML Implementation of Simple Types Chapter 11 - Simple Extensions Chapter 12 - Normalization Chapter 13 - References Chapter 14 - Exceptions Part III - Subtyping Chapter 15 - Subtyping Chapter 16 - Metatheory of Subtyping Chapter 17 - An ML Implementation of Subtyping Chapter 18 - Case Study: Imperative Objects Chapter 19 - Case Study: Featherweight Java Part IV - Recursive Types Chapter 20 - Recursive Types Chapter 21 - Metatheory of Recursive Types Part V - Polymorphism Chapter 22 - Type Reconstruction Chapter 23 - Universal Types Chapter 24 - Existential Types Chapter 25 - An ML Implementation of System F Chapter 26 - Bounded Quantification Chapter 27 - Case Study: Imperative Objects, Redux Chapter 28 - Metatheory of Bounded Quantification Part VI - Higher-Order Systems Chapter 29 - Type Operators and Kinding Chapter 30 - Higher-Order Polymorphism Chapter 31 - Higher-Order Subtyping Chapter 32 - Case Study: Purely Functional Objects Part VII - Appendices Appendix A - Solutions to Selected Exercises Appendix B - Notational Conventions References Index List of Figures < Free Open Study > < Free Open Study > Back Cover A type system is a syntactic method for automatically checking the absence of certain erroneous behaviors by classifying program phrases according to the kinds of values they compute. -

LATEX for Beginners

LATEX for Beginners Workbook Edition 5, March 2014 Document Reference: 3722-2014 Preface This is an absolute beginners guide to writing documents in LATEX using TeXworks. It assumes no prior knowledge of LATEX, or any other computing language. This workbook is designed to be used at the `LATEX for Beginners' student iSkills seminar, and also for self-paced study. Its aim is to introduce an absolute beginner to LATEX and teach the basic commands, so that they can create a simple document and find out whether LATEX will be useful to them. If you require this document in an alternative format, such as large print, please email [email protected]. Copyright c IS 2014 Permission is granted to any individual or institution to use, copy or redis- tribute this document whole or in part, so long as it is not sold for profit and provided that the above copyright notice and this permission notice appear in all copies. Where any part of this document is included in another document, due ac- knowledgement is required. i ii Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is LATEX?..........................1 1.2 Before You Start . .2 2 Document Structure 3 2.1 Essentials . .3 2.2 Troubleshooting . .5 2.3 Creating a Title . .5 2.4 Sections . .6 2.5 Labelling . .7 2.6 Table of Contents . .8 3 Typesetting Text 11 3.1 Font Effects . 11 3.2 Coloured Text . 11 3.3 Font Sizes . 12 3.4 Lists . 13 3.5 Comments & Spacing . 14 3.6 Special Characters . 15 4 Tables 17 4.1 Practical . -

The Gnu Binary Utilities

The gnu Binary Utilities Version cygnus-2.7.1-96q4 May 1993 Roland H. Pesch Jeffrey M. Osier Cygnus Support Cygnus Support TEXinfo 2.122 (Cygnus+WRS) Copyright c 1991, 92, 93, 94, 95, 1996 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modi®ed versions of this manual under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided also that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this manual into another language, under the above conditions for modi®ed versions. The GNU Binary Utilities Introduction ..................................... 467 1ar.............................................. 469 1.1 Controlling ar on the command line ................... 470 1.2 Controlling ar with a script ............................ 472 2ld.............................................. 477 3nm............................................ 479 4 objcopy ....................................... 483 5 objdump ...................................... 489 6 ranlib ......................................... 493 7 size............................................ 495 8 strings ........................................ 497 9 strip........................................... 499 Utilities 10 c++®lt ........................................ 501 11 nlmconv .................................... -

Factor — Factor Analysis

Title stata.com factor — Factor analysis Description Quick start Menu Syntax Options for factor and factormat Options unique to factormat Remarks and examples Stored results Methods and formulas References Also see Description factor and factormat perform a factor analysis of a correlation matrix. The commands produce principal factor, iterated principal factor, principal-component factor, and maximum-likelihood factor analyses. factor and factormat display the eigenvalues of the correlation matrix, the factor loadings, and the uniqueness of the variables. factor expects data in the form of variables, allows weights, and can be run for subgroups. factormat is for use with a correlation or covariance matrix. Quick start Principal-factor analysis using variables v1 to v5 factor v1 v2 v3 v4 v5 As above, but retain at most 3 factors factor v1-v5, factors(3) Principal-component factor analysis using variables v1 to v5 factor v1-v5, pcf Maximum-likelihood factor analysis factor v1-v5, ml As above, but perform 50 maximizations with different starting values factor v1-v5, ml protect(50) As above, but set the seed for reproducibility factor v1-v5, ml protect(50) seed(349285) Principal-factor analysis based on a correlation matrix cmat with a sample size of 800 factormat cmat, n(800) As above, retain only factors with eigenvalues greater than or equal to 1 factormat cmat, n(800) mineigen(1) Menu factor Statistics > Multivariate analysis > Factor and principal component analysis > Factor analysis factormat Statistics > Multivariate analysis > Factor and principal component analysis > Factor analysis of a correlation matrix 1 2 factor — Factor analysis Syntax Factor analysis of data factor varlist if in weight , method options Factor analysis of a correlation matrix factormat matname, n(#) method options factormat options matname is a square Stata matrix or a vector containing the rowwise upper or lower triangle of the correlation or covariance matrix. -

Dell EMC Powerstore CLI Guide

Dell EMC PowerStore CLI Guide May 2020 Rev. A01 Notes, cautions, and warnings NOTE: A NOTE indicates important information that helps you make better use of your product. CAUTION: A CAUTION indicates either potential damage to hardware or loss of data and tells you how to avoid the problem. WARNING: A WARNING indicates a potential for property damage, personal injury, or death. © 2020 Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries. All rights reserved. Dell, EMC, and other trademarks are trademarks of Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries. Other trademarks may be trademarks of their respective owners. Contents Additional Resources.......................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Introduction................................................................................................................... 5 Overview.................................................................................................................................................................................5 Use PowerStore CLI in scripts.......................................................................................................................................5 Set up the PowerStore CLI client........................................................................................................................................5 Install the PowerStore CLI client.................................................................................................................................. -

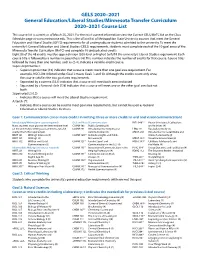

General Education and Liberal Studies Course List

GELS 2020–2021 General Education/Liberal Studies/Minnesota Transfer Curriculum 2020–2021 Course List This course list is current as of March 25, 2021. For the most current information view the Current GELS/MnTC list on the Class Schedule page at www.metrostate.edu. This is the official list of Metropolitan State University courses that meet the General Education and Liberal Studies (GELS) requirements for all undergraduate students admitted to the university. To meet the university’s General Education and Liberal Studies (GELS) requirements, students must complete each of the 10 goal areas of the Minnesota Transfer Curriculum (MnTC) and complete 48 unduplicated credits. Eight (8) of the 48 credits must be upper division (300-level or higher) to fulfill the university’s Liberal Studies requirement. Each course title is followed by a number in parenthesis (4). This number indicates the number of credits for that course. Course titles followed by more than one number, such as (2-4), indicate a variable-credit course. Superscript Number: • Superscript number (10) indicates that a course meets more than one goal area requirement. For example, NSCI 20410 listed under Goal 3 meets Goals 3 and 10. Although the credits count only once, the course satisfies the two goal area requirements. • Separated by a comma (3,LS) indicates that a course will meet both areas indicated. • Separated by a forward slash (7/8) indicates that a course will meet one or the other goal area but not both. Superscript LS (LS): • Indicates that a course will meet the Liberal Studies requirement. Asterisk (*): • Indicates that a course can be used to meet goal area requirements, but cannot be used as General Education or Liberal Studies Electives. -

Computer Matching Agreement

COMPUTER MATCHING AGREEMENT BETWEEN NEW tvIEXICO HUMAN SERVICES DEPARTMENT AND UNIVERSAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATIVE COMPANY AND THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION INTRODUCTION This document constitutes an agreement between the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC or Commission), and the New Mexico Human Services Department (Department) (collectively, Parties). The purpose of this Agreement is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the Universal Service Fund (U SF’) Lifeline program, which provides support for discounted broadband and voice services to low-income consumers. Because the Parties intend to share information about individuals who are applying for or currently receive Lifeline benefits in order to verify the individuals’ eligibility for the program, the Parties have determined that they must execute a written agreement that complies with the Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act of 1988 (CMPPA), Public Law 100-503, 102 Stat. 2507 (1988), which was enacted as an amendment to the Privacy Act of 1974 (Privacy Act), 5 U.S.C. § 552a. By agreeing to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, the Parties intend to comply with the requirements of the CMPPA that are codified in subsection (o) of the Privacy Act. 5 U.S.C. § 552a(o). As discussed in section 11.B. below, U$AC has been designated by the FCC as the permanent federal Administrator of the Universal Service funds programs, including the Lifeline program that is the subject of this Agreement. A. Title of Matching Program The title of this matching program as it will be reported by the FCC and the Office of Management and Budget (0MB) is as follows: “Computer Matching Agreement with the New Mexico Human Services Department.” B. -

Project1: Build a Small Scanner/Parser

Project1: Build A Small Scanner/Parser Introducing Lex, Yacc, and POET cs5363 1 Project1: Building A Scanner/Parser Parse a subset of the C language Support two types of atomic values: int float Support one type of compound values: arrays Support a basic set of language concepts Variable declarations (int, float, and array variables) Expressions (arithmetic and boolean operations) Statements (assignments, conditionals, and loops) You can choose a different but equivalent language Need to make your own test cases Options of implementation (links available at class web site) Manual in C/C++/Java (or whatever other lang.) Lex and Yacc (together with C/C++) POET: a scripting compiler writing language Or any other approach you choose --- must document how to download/use any tools involved cs5363 2 This is just starting… There will be two other sub-projects Type checking Check the types of expressions in the input program Optimization/analysis/translation Do something with the input code, output the result The starting project is important because it determines which language you can use for the other projects Lex+Yacc ===> can work only with C/C++ POET ==> work with POET Manual ==> stick to whatever language you pick This class: introduce Lex/Yacc/POET to you cs5363 3 Using Lex to build scanners lex.yy.c MyLex.l lex/flex lex.yy.c a.out gcc/cc Input stream a.out tokens Write a lex specification Save it in a file (MyLex.l) Compile the lex specification file by invoking lex/flex lex MyLex.l A lex.yy.c file is generated -

LS JK BUILDER KIT 2007-2011 Jeep Wrangler JK Installation Guide

LS JK BUILDER KIT 2007-2011 Jeep Wrangler JK Installation Guide Install Guide © Table of contents: Preface………………………………………………………………… ………………….….….…3 Part 1 Power options…………………………………………………………………….….…..…4 Part 2 The LS JK…………………………………………………………………………….….….6 Part 3 LS engines…………………………………………………………………………….….…7 Part 4 Operating systems………………………………………………………………………..10 Part 5 Gen IV LS engine features……………………………………………………………….11 Part 6 Transmissions……………………………………………………………………………..12 Part 7 Transfer cases……………………………………………………………………………..13 Part 8 MoTech basic builder kit contents……………………………………………………….14 Part 9 MoTech basic builder kit photo ID table…………………………………………………18 Part 10 MoTech Basic Kit Installation Overview and Shop Tools Required………………...20 Part 11 Prepping the vehicle………………………………………………………………..……21 Part 12 Removing the body……………………………………………………………………....21 Part 13 Prepping the chassis…………………………………………………………………..…28 Part 14 Installing the powertrain………………………………………………………………….31 Part 15 Accessory drive………………………………………………… ………………………36 Part 16 Wiring the LS JK…………………………………………………………………………..39 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………………………52 Pentstar fan installation……………………………………………………………………52 Wiring diagrams…………………………………………………………………………….53 241J Input gear installation………………………………………………………………..56 Manual to automatic conversion……………………………………………………….….81 Torque specification GM and Jeep……………………………………………………….83 Radiator hose guide…………………………………………………………………...…...86 LS JK master part list…………………………………………………………………........87 2 Install Guide © Preface: The Wrangler -

GNU M4, Version 1.4.7 a Powerful Macro Processor Edition 1.4.7, 23 September 2006

GNU M4, version 1.4.7 A powerful macro processor Edition 1.4.7, 23 September 2006 by Ren´eSeindal This manual is for GNU M4 (version 1.4.7, 23 September 2006), a package containing an implementation of the m4 macro language. Copyright c 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 2004, 2005, 2006 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” i Table of Contents 1 Introduction and preliminaries ................ 3 1.1 Introduction to m4 ............................................. 3 1.2 Historical references ............................................ 3 1.3 Invoking m4 .................................................... 4 1.4 Problems and bugs ............................................. 8 1.5 Using this manual .............................................. 8 2 Lexical and syntactic conventions ............ 11 2.1 Macro names ................................................. 11 2.2 Quoting input to m4........................................... 11 2.3 Comments in m4 input ........................................ 11 2.4 Other kinds of input tokens ................................... 12 2.5 How m4 copies input to output ................................ 12 3 How to invoke macros........................ -

LINUX INTERNALS LABORATORY III. Understand Process

LINUX INTERNALS LABORATORY VI Semester: IT Course Code Category Hours / Week Credits Maximum Marks L T P C CIA SEE Total AIT105 Core - - 3 2 30 70 100 Contact Classes: Nil Tutorial Classes: Nil Practical Classes: 36 Total Classes: 36 OBJECTIVES: The course should enable the students to: I. Familiar with the Linux command-line environment. II. Understand system administration processes by providing a hands-on experience. III. Understand Process management and inter-process communications techniques. LIST OF EXPERIMENTS Week-1 BASIC COMMANDS I Study and Practice on various commands like man, passwd, tty, script, clear, date, cal, cp, mv, ln, rm, unlink, mkdir, rmdir, du, df, mount, umount, find, unmask, ulimit, ps, who, w. Week-2 BASIC COMMANDS II Study and Practice on various commands like cat, tail, head , sort, nl, uniq, grep, egrep,fgrep, cut, paste, join, tee, pg, comm, cmp, diff, tr, awk, tar, cpio. Week-3 SHELL PROGRAMMING I a) Write a Shell Program to print all .txt files and .c files. b) Write a Shell program to move a set of files to a specified directory. c) Write a Shell program to display all the users who are currently logged in after a specified time. d) Write a Shell Program to wish the user based on the login time. Week-4 SHELL PROGRAMMING II a) Write a Shell program to pass a message to a group of members, individual member and all. b) Write a Shell program to count the number of words in a file. c) Write a Shell program to calculate the factorial of a given number.