Edited & Excerpted Transcript of the Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election Results

MCLEAN COUNTY ABSTRACT OF BALLOTS CAST NORTH DAKOTA PRIMARY ELECTION ‐ JUNE 10, 2014 District Precinct Ballots Cast LG04 LEGISLATIVE 4‐McLEAN LESS 0402 337 WHITE SHIELD/ZIEGLER RURAL 64 Subtotal 401 LG08 LEGISLATIVE 8‐McLEAN COUNTY 2,347 Subtotal 2,347 Total 2,748 LEGISLATIVE 4 ‐ LEGISLATIVE 8 ‐ WHITE Total McLEAN LESS McLEAN SHIELD/ZIEGLER 0402 COUNTY RURAL REPUBLICAN Representative in Congress Kevin Cramer 1577 167 1390 20 write‐in ‐ scattered 2 02 0 Total 1579 167 1392 20 Secretary of State Alvin A (Al) Jaeger 1565 161 1385 19 write‐in ‐ scattered 1 01 0 Total 1566 161 1386 19 Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem 1570 161 1390 19 write‐in ‐ scattered 0 00 0 Total 1570 161 1390 19 Agriculture Commissioner Doug Goehring 1540 159 1362 19 write‐in ‐ scattered 0 00 0 Total 1540 159 1362 19 Public Service Commissioner Brian P Kalk 1521 159 1343 19 write‐in ‐ scattered 0 00 0 Total 1521 159 1343 19 Public Service Commissioner Unexpired Julie Fedorchak 1527 159 1349 19 2‐Year Term write‐in ‐ scattered 0 00 0 Total 1527 159 1349 19 Tax Commissioner Ryan Rauschenberger 1527 157 1351 19 write‐in ‐ scattered 2 02 0 Total 1529 157 1353 19 DEMOCRATIC‐NPL Representative in Congress George Sinner 745 98 608 39 write‐in ‐ scattered 1 10 0 Total 746 99 608 39 Secretary of State April Fairfield 702 94 573 35 write‐in ‐ scattered 1 01 0 Total 703 94 574 35 Attorney General Kiara Kraus‐Parr 687 93 558 36 write‐in ‐ scattered 2 02 0 Total 689 93 560 36 Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Taylor 761 105 621 35 write‐in ‐ scattered 1 01 0 Total 762 105 622 35 Public -

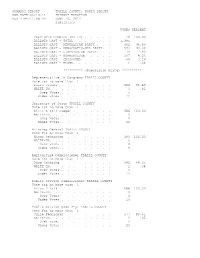

Summary Report Traill County, North Dakota Run Date:06/10/14 Primary Election Run Time:11:08 Pm June 10, 2014 Statistics

SUMMARY REPORT TRAILL COUNTY, NORTH DAKOTA RUN DATE:06/10/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:11:08 PM JUNE 10, 2014 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 12) . 12 100.00 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 1,295 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN PARTY . 602 46.49 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC-NPL PARTY. 574 44.32 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN PARTY. 12 .93 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 107 8.26 BALLOTS CAST - CROSSOVER . 66 5.10 BALLOTS CAST - BLANK. 1 .08 ********** (Republican Party) ********** Representative in Congress TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Kevin Cramer . 586 99.49 WRITE-IN. 3 .51 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 13 Secretary of State TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Alvin A (Al) Jaeger . 586 100.00 WRITE-IN. 0 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 16 Attorney General TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Wayne Stenehjem . 593 100.00 WRITE-IN. 0 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 9 Agriculture Commissioner TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Doug Goehring . 586 99.66 WRITE-IN. 2 .34 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 14 Public Service Commissioner TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Brian P Kalk . 588 100.00 WRITE-IN. 0 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 14 Public Service Comm 2-yr TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Julie Fedorchak . 577 99.65 WRITE-IN. 2 .35 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 23 Tax Commissioner TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 Ryan Rauschenberger . 578 99.83 WRITE-IN. 1 .17 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 23 ********** (Democratic-NPL Party) ********** Representative in Congress TRAILL COUNTY Vote for no more than 1 George Sinner . -

Directory Governor Doug Burgum North Dakota Legislative Hotline: Lt Governor Brent Sanford for 1-888-635-3447 Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem

North Dakota Elected Officials Reach Your Legislators Directory Governor Doug Burgum North Dakota Legislative Hotline: Lt Governor Brent Sanford for 1-888-635-3447 Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem Secretary of Al Jaeger Bismarck Area: 328-3373 State Legislative Web Site: Treasurer Kelly Schmidt www.legis.nd.gov 66th North Dakota Auditor Josh Gallion Legislative Assembly and Superintendent Kirsten Baesler of Public Join the North Dakota Catholic Elected Officials Instruction Conference Legislative Action Agricultural Doug Goehring Network Commissioner Sign-up at: ndcatholic.org/ Insurance Jon Godfread registration/ Commissioner Or contact the North Dakota Tax Ryan Rauschenberger Catholic Conference at: Commissioner (701) 223-2519 Public Service Brian Kroshus Commissioners Julie Fedorchak 1-888-419-1237 Randy Christmann [email protected] North Dakota Catholic Conference 103 South Third Street, No. 10 Bismarck, North Dakota 58501 U.S. Senator John Hoeven Christopher T. Dodson U.S. Senator Kevin Cramer Follow Us Executive Director U.S. Kelly Armstrong Representative (701) 223-2519 1-888-419-1237 Get contact information for all [email protected] state officials at nd.gov. www.facebook.com/ndcatholic ndcatholic.org Senate House of Representatives Howard C. Anderson, [email protected] 8 Patrick Hatlestad [email protected] 1 Dwight Kiefert [email protected] 24 JoNell A. Bakke [email protected] 43 David Richter [email protected] 1 Alisa Mitskog [email protected] 25 Brad Bekkedahl [email protected] 1 Bert Anderson [email protected] 2 Cynthia Schreiber-Beck [email protected] 25 Randy Burckhard [email protected] 5 Donald W. Longmuir [email protected] 2 Sebastian Ertelt [email protected] 26 David A. -

Sample General Election Ballot

SAMPLE GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT D STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA E GRAND FORKS F UND Wellness Center 21 To vote for the candidate of your choice, you must darken the oval next to the name of that United States Senator State Representative candidate. Vote for no more than ONE name District 42 Vote for no more than TWO names To vote for a person whose name is not printed James Germalic on the ballot, you must darken the oval next to Emily O'Brien the blank line provided and write that person's independent nomination Republican Party name on the blank line. Eliot Glassheim Jake Blum Democratic-NPL Party PARTY BALLOT Republican Party Robert N Marquette Grant D Hauschild Libertarian Party President & Vice-President of the Democratic-NPL Party United States John Hoeven Vote for no more than ONE name Kylie Oversen Republican Party Presidential Electors Democratic-NPL Party Write-in Jeffrey Eide Write-in STEIN Michael Lopez Green Party { Jason Anderson } Write-in Representative in Congress Vote for no more than ONE name John Olson Governor and Lt. Governor TRUMP Duane Mutch Kevin Cramer Republican Party Vote for no more than ONE set of names { Beverly Clayburgh} Republican Party Doug Burgum Jack Seaman & Brent Sanford Libertarian Party DE LA Michael P Cohen Republican Party Jordon Lee Rosdahl Chase Iron Eyes FUENTE { Cory Hukriede } Marvin E Nelson American Delta Party Democratic-NPL Party & Joan Heckaman Democratic-NPL Party Write-in Robert Valeu Marty Riske CLINTON Grace Link Democratic-NPL Party { Darlene Turitto } & Joshua Voytek State Senator Libertarian -

November 4, 2014 Official Results Morton County 2014 General Election

Official Results Morton County 2014 General Election November 4, 2014 Candidates TOTALS Precinct 01 - Spirit of LifePrecinctCatholicSpirit01of - Church PrecinctMidway02- Lanes PrecinctMandaan03- Eagles PrecinctMandan04- Eagles PrecinctMandan05- Eagles Lutheran PrecinctFirst 06- Church Lutheran PrecinctFirst 07- Church LifePrecinctCatholicSpirit08of - Church Church Nazarenethe Precinct First 17of - PrecinctMidway18- Lanes PrecinctFlasher20- Community Credit Union Anthony HallPrecinctSt 23- PrecinctMandan24- Airport Church Nazarenethe Precinct First 32of - PrecinctNew33- Salem AuditoriumCity PrecinctAlmont34Memorial- Hall PrecinctGlen36Ullin- HallCity PrecinctHebron38- Community Center Voters Early Voting 1511 155 171 117 128 85 167 75 40 157 92 6 19 90 184 14 5 6 0 Voters Absentee 2122 197 287 157 115 95 145 90 102 232 108 34 44 77 210 65 20 84 60 Voters Election Day 7798 820 817 469 495 321 533 337 347 769 350 165 140 350 647 570 97 307 264 Voters Canvassing 21 2 3 3 0 0 1 2 0 4 0 0 0 1 3 0 0 2 0 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL 11452 1174 1278 746 738 501 846 504 489 1162 550 205 203 518 1044 649 122 399 324 Representative in Congress Kevin Cramer 6626 678 803 355 400 232 418 224 232 692 322 135 116 350 638 425 85 292 229 Robert J "Jack" Seaman 704 75 57 64 37 26 60 38 37 94 36 12 14 23 70 23 6 19 13 George Sinner 3813 387 374 297 277 236 347 233 201 349 177 54 66 127 319 182 28 81 78 write-in - scattered 23 5 2 3 3 0 2 0 0 0 1 1 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 State Senator District 33 Jessica Unruh 1462 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 841 523 98 -

2016 General Election

Official Results 2016 General Election Candidates TOTALS J1 Precinct J2 Precinct J3 Precinct J5 Precinct J6 Precinct P1 Precinct P2 Precinct P3 Precinct P4 Precinct P5 Precinct P6 Precinct J4 Precinct BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL 10345 1281 1837 1255 1237 936 262 189 409 743 540 665 991 BALLOTS CAST - BLANK BALLOTS CAST - BLANK 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 CASTLE 55 8 4 7 6 3 0 2 5 5 6 2 7 JOHNSON 574 79 104 87 85 51 5 8 32 35 14 24 50 DE LA FUENTE 13 2 4 0 3 1 0 0 1 0 0 2 0 STEIN 109 16 17 21 18 16 1 4 1 5 3 2 5 President & Vice - President of the U.S. STUTSMAN COUNTY CLINTON 2498 362 518 316 342 233 47 40 83 128 70 136 223 TRUMP 6718 755 1119 790 724 598 199 133 275 541 433 482 669 OVER VOTES 13 1 1 2 2 3 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 UNDER VOTES 177 28 35 18 28 14 6 2 5 10 2 10 19 Eliot Glassheim 1329 189 280 177 205 123 20 17 37 72 37 66 106 Robert N Marquette 222 32 31 29 35 15 5 8 12 22 11 5 17 John Hoeven 8392 1003 1457 987 943 749 229 157 349 627 481 581 829 United States Senator STUTSMAN COUNTY James Germalic 137 10 18 21 26 16 2 4 2 13 6 7 12 OVER VOTES 5 2 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 UNDER VOTES 253 44 49 40 28 31 5 3 8 9 3 6 27 Jack Seaman 661 81 104 93 86 65 20 21 30 40 26 38 57 Chase Iron Eyes 2174 304 415 276 322 214 42 29 76 139 72 114 171 Representative in Congress STUTSMAN COUNTY Kevin Cramer 7001 819 1216 810 774 609 193 132 288 535 425 493 707 OVER VOTES 6 0 2 1 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 UNDER VOTES 494 76 98 73 52 45 7 7 14 29 17 20 56 John Grabinger 3673 659 1031 722 743 518 Katie Andersen 2563 532 722 482 451 376 State Senator DISTRICT -

Propane Marketers

North Dakota Petroleum Marketers Association Protecting Your Business Interests In North Dakota and Washington, D.C. Membership Directory • 2020-2021 A Perfect Fit for Protecting Your American Dream Our partnership with your association has one goal: helping your business succeed. You deserve an insurance provider who understands your industry. Put our knowledge and experience to work for you. Scan to learn more about an industry-specific insurance program designed for your business. Commercial Insurance Property & Casualty | Life & Disability Income | Workers Compensation Business Succession and Estate Planning | Bonding Federated Mutual Insurance Company and its subsidiaries* | federatedinsurance.com Ward’s 50® Top Performer | A.M. Best® A+ (Superior) Rating 20.01 Ed. 12/19 *Not licensed in all states. © 2019 Federated Mutual Insurance Company Table of Contents Petroleum Board of Directors ...................................... 3 Propane Hall of Fame .................................................51 Chairman’s Welcome....................................................5 Propane Marketers ......................................................52 Petroleum Hall of Fame ............................................... 7 Propane Associates .....................................................56 Public Relations .............................................................9 ND Elected Officials ....................................................58 NDPMA History & Mission ........................................11 State Government Agencies -

2016 General Election

BARNES COUNTY ABSTRACT OF BALLOTS CAST NORTH DAKOTA GENERAL ELECTION - NOVEMBER 08, 2016 District Precinct Name Ballots Cast LG24 Precinct 2401-00 427 Precinct 2402-00 693 Precinct 2403-00 470 Precinct 2404-00 641 Precinct 2405-00 855 Precinct 2406-00 330 Precinct 2407-00 135 Precinct 2408-00 159 Precinct 2409-00 228 Precinct 2410-00 89 Precinct 2411-00 594 Precinct 2412-00 259 Precinct 2413-00 266 Precinct 2414-00 101 Precinct 2415-00 204 Subtotal 5451 Total 5451 1 of 1 BARNES COUNTY ABSTRACT OF VOTES NORTH DAKOTA GENERAL ELECTION - NOVEMBER 08, 2016 Precinct 2403-00 Precinct 2413-00 Precinct Precinct 2401-00 Precinct 2402-00 Precinct 2404-00 Precinct 2405-00 Precinct 2406-00 Precinct 2407-00 Precinct 2408-00 Precinct 2409-00 Precinct 2410-00 Precinct 2411-00 Precinct 2412-00 Precinct 2414-00 Precinct 2415-00 Precinct Total President & Vice-President CASTLE 41 2 3 3 3 3 3 5 0 4 0 7 2 6 0 0 of the United States Constitution CLINTON 1,597 141 233 164 205 289 91 31 28 46 28 144 59 68 25 45 Democratic-NPL DE LA FUENTE 6 0 1 2 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 American Delta JOHNSON 407 29 53 40 51 66 19 15 10 24 5 39 17 25 7 7 Libertarian STEIN 47 2 9 8 5 10 3 0 0 0 0 5 4 1 0 0 Green TRUMP 3,160 240 372 230 347 451 206 80 114 151 54 380 168 156 65 146 Republican write-in - scattered 86 5 11 12 11 18 5 3 3 0 1 11 0 4 0 2 Total 5,344 419 682 459 623 839 327 134 155 225 88 586 250 260 97 200 United States Senator James Germalic independent nomination 56 3 2 13 8 8 6 2 2 2 2 3 1 3 0 1 Eliot Glassheim 835 63 131 92 103 140 52 19 12 19 17 78 29 39 18 23 -

STATE of NORTH DAKOTA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Notice

STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Notice with Agenda Meeting of October 8, 2018 Time: 08:00 a.m. Location: Bismarck State College National Energy Center of Excellence Re: Great Plains & EmPower ND Energy Conference Agenda: Highlights for this year’s conference include a keynote presentation from U.S. Department of Energy Deputy Secretary Dan Brouillette and a roundtable Q&A with guests U.S. Senators John Hoeven and Heidi Heitkamp, and Congressman Kevin Cramer. North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum will also be participating. Prepared by: Darrell Nitschke Date: 30 August 2018 Telephone: 701-328-4098 O-180 U.S. Senator U.S. Senator Congressman N.D. Governor John Hoeven Heidi Heitkamp Kevin Cramer Doug Burgum EmPower ND • BSC • Great Plains Energy Corridor • KLJ • ND Dept of Commerce *Speakers and Times Subject to Change* MONDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2018 7:45 am Registration and Continental Breakfast 8:05 am Welcome from Dr. Larry C. Skogen, President, Bismarck State College 8:10 am All of the Above: The Big Picture in State and National Energy Policy North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum United States Senator John Hoeven United States Senator Heidi Heitkamp Congressman Kevin Cramer Moderator: Jason Bohrer, President and CEO, Lignite Energy Council The energy industry is facing challenges, but North Dakota leads the way in demonstrating what is needed to create a strong, affordable, and diverse energy mix. Hear from the state’s leaders on what they see as a critical need in shaping the state’s energy future and get the chance to text in your questions during this live Q&A discussion. -

2019 Biennial Report

Public Service Commission Brian Kroshus Julie Fedorchak Randy Christmann Chairman Commissioner Commissioner PeriodPeriod ofof JulyJuly 1,1, 20172017 throughthrough JuneJune 30,30, 20192019 Biennial Report Table of Contents Introduction/History ......................................................................................................................1 Commissioners Commissioner Brian Kroshus ..................................................................................................2 Commissioner Julie Fedorchak ............................................................................................... 3 Commissioner Randy Christmann ...........................................................................................4 Agency Overview .........................................................................................................................6 Executive Secretary .................................................................................................................6 Mission Statement ...................................................................................................................7 Public Outreach........................................................................................................................7 Financial Management .............................................................................................................8 General Counsel .......................................................................................................................9 -

E F E F E F E F E F

“The arrangement of candidate names appearing on ballots in your precinct may vary from the published sample ballots, depending upon the precinct and legislative district in which you reside.” SAMPLE BALLOT GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT NOVEMBER 8, 2016 A STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA B BURLEIGH COUNTY C Insurance Commissioner To vote for the candidate of your choice, you Governor and Lt. Governor Vote for no more than ONE name must darken the oval ( R ) next to the name Vote for no more than ONE set of names of that candidate. Ruth Buffalo To vote for a person whose name is not Democratic-NPL Party printed on the ballot, you must darken the oval Doug Burgum ( ) next to the blank line provided and Nick Bata R & Brent Sanford Libertarian Party write that person's name on the blank line. Republican Party Jon Godfread Republican Party PARTY BALLOT Marty Riske & Joshua Voytek Libertarian Party President & Vice-President of the Public Service Commissioner United States Vote for no more than ONE name Vote for no more than ONE name Marvin E Nelson Thomas Skadeland & Joan Heckaman Libertarian Party Democratic-NPL Party Presidential Electors Julie Fedorchak Republican Party Robert Valeu CLINTON Grace Link Marlo Hunte-Beaubrun Democratic-NPL Party E Darlene TurittoF Democratic-NPL Party State Auditor Vote for no more than ONE name DE LA FUENTE Michael P Cohen Jordon Lee Rosdahl Roland Riemers NO-PARTY BALLOT American Delta Party E Cory HukriedeF Libertarian Party Josh Gallion To vote for the candidate of your choice, you Republican Party must darken the oval ( R ) next to the name Jack Seaman of that candidate. -

Another Eagle Scout in the Friedt Family by Kathy Kennedy One of His Favorites

Subscribe to our online issues of The Herald-Press The www.heraldpressnd.com Vol. 32 Issue 48 75¢ Saturday, November 26, 2016 Herald-Press - Official Newspaper of Wells County - Harvey and Fessenden, North Dakota- at www. heraldpressnd.com Another Eagle Scout in the Friedt family by Kathy Kennedy one of his favorites. Personal Fit- others, Friedt recruited the aid of Boy Scout Troop #534 of Har- ness was a challenge as he kept his brothers, Kevin and Nathan, vey has a new Eagle Scout. Brian track of all physical activities for along with Reinowski’s expertise Friedt, 15, and son of Mark and a 12-week period. and assistance. Friedt’s father Send us your Dawn Friedt, Harvey, officially helped and served as his project received this rank at his Court His community project coach. The goal was to have the of Honor ceremony Sunday, nature photos Brian’s community service new Harvey championship signs Oct. 23. project that was required to move up before the All-School Reunion This event was held at Faith As the seasons change, we to Eagle rank involved replacing in July. The goal was met. Lutheran Church. Brian’s broth- have added to our website's photo the signs for the Harvey Boosters Once the physical work for er, Kevin, who is also an Eagle series “North Dakota In Nature.” Club that were along the high- the project of replacing signs was Scout, served as Master of Cer- Submit your photos to us at way west of Harvey. From March completed, Friedt set out to finish emony.