Greening Bonnaroo: Exploring the Rhetoric and the Reality of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Music Sustainable: the Ac Se of Marketing Summer Jamband Festivals in the U.S., 2010 Melissa A

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2012 Making Music Sustainable: The aC se of Marketing Summer Jamband Festivals in the U.S., 2010 Melissa A. Cary Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Cary, Melissa A., "Making Music Sustainable: The asC e of Marketing Summer Jamband Festivals in the U.S., 2010" (2012). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1206. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1206 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAKING MUSIC SUSTAINABLE: THE CASE OF MARKETING SUMMER JAMBAND FESTIVALS IN THE U.S., 2010 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Geography and Geology Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science By Melissa A. Cary August 2012 I dedicate this thesis to the memory my grandfather, Glen E. Cary, whose love and kindness is still an inspiration to me. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS During the past three years there have been many people who have supported me during the process of completing graduate school. First and foremost, I would like to thank the chair of my thesis committee, Dr. Margaret Gripshover, for helping me turn my love for music into a thesis topic. -

Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide

Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide Overview of Tennessee Key Facts Language: English is the most common language spoken but Spanish is often heard in the south-western states. Passport/Visa: Currency: Electricity: Electrical current is 120 volts, 60Hz. Plugs are mainly the type with two flat pins, though three-pin plugs (two flat parallel pins and a rounded pin) are also widely used. European appliances without dual-voltage capabilities will require an adapter. Travel guide by wordtravels.com © Globe Media Ltd. By its very nature much of the information in this travel guide is subject to change at short notice and travellers are urged to verify information on which they're relying with the relevant authorities. Travmarket cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Event details can change. Please check with the organizers that an event is happening before making travel arrangements. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Page 1/8 Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide Travel to Tennessee Climate for Tennessee Health Notes when travelling to United States of America Safety Notes when travelling to United States of America Customs in United States of America Duty Free in United States of America Doing Business in United States of America Communication in United States of America Tipping in United States of America Passport/Visa Note Page 2/8 Tennessee, United States of America Destination Guide Airports in Tennessee Memphis International (MEM) Memphis International Airport www.flymemphis.com Location: Memphis The airport is situated seven miles (11km) southeast from Memphis. -

Mass Gatherings, Health, and Well‐Being

Social Issues and Policy Review, Vol. 00, No. 0, 2020, pp. 1--32 DOI: 10.1111/sipr.12071 Mass Gatherings, Health, and Well-Being: From Risk Mitigation to Health Promotion ∗ Nick Hopkins University of Dundee Stephen Reicher University of St. Andrews Mass gatherings are routinely viewed as posing risks to physical health. How- ever, social psychological research shows mass gathering participation can also bring benefits to psychological well-being. We describe how both sets of outcomes can be understood as arising from the distinctive forms of behavior that may be found when people—even strangers—come to define themselves and each other in terms of a shared social identity. We show that many of the risks and benefits of participation are products of group processes; that these different outcomes can have their roots in the same core processes; and that knowledge of these process provides a basis for health promotion interventions to mitigate the risks and max- imize the benefits of participation. Throughout, we offer practical guidance as to how policy makers and practitioners should tailor such interventions. Mass gatherings take many forms: large-scale religious pilgrimages (e.g., the hajj), sporting events (e.g., the World Cup), music festivals (e.g., Glaston- bury), regional and national commemorative events (e.g., St Patrick’s Day cele- brations), etc. Some are short-lived, others span days, even weeks. Some attract a few thousand, others, hundreds of thousands. Perhaps the most striking of all are the Kumbh Mela and the Magh Mela, each of which attract millions of Hindu pil- grims to the banks of the Ganga (north India) for a full month (Buzinde, Kalavar, Kohli, & Manuel-Navarrete, 2014; Hopkins et al., 2015; Maclean, 2008). -

10,000 SEATS Time Has Been a Friend to Lolla- Angeles

Clockwise from left: London's top festival finalist Download; top amphitheater finalist Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Morrison, Colo.; MARCO ANTONIO SOUS at under -10,000 finalist Auditorio Nacional in Mexico City; inset: San Francisco's Fillmore, finalist for top club. Morrison, Colo.; the Tweeter Center for the Performing TOP VENUE UNDER partner in LoL'a producer C3, says Arts in Mansfield, Mass.; and the Greek Theatre in Los 10,000 SEATS time has been a friend to Lolla- Angeles. Tweeter Center has been finalist for top am- (NONRESIDENT) palooza, in its third year as a resur- phitheater three years running, winning in 2004 and 2005. Venues of 10,000 seats or fewer have rected brand and stand -alone event. Red Rocks is known for passionate fans and m-iltiple become the sweet spot for many tour- "Like most of the festivals, it takes a dates by artists. "We enjoyed a record -breaking summer ing artis:s today, and the three finalists in little while to get momentum going," concert season, with 20 more bookings than any other this category exemplify their potential and Walker says. "We had a great lineup this year, year in the amphitheater's 46 -year history," Red Rocks chief range: Auditorio Nacional in Mexico City, the but more importantly, we had repeat fans, peo- marketing officer Erik Dyce says. "We're thrilled to be con- Fox Theatre in Atlanta and the Gibson ple have become familiar with Grant Park, and it re- sidered for the top amphitheater honor and are Amphitheatre at Universal Citywalk in Univer- ally helps that Chicago is such a great town." enormously proud of our accomplishments this ial City, Calif. -

Tour Dates May, June & July

TOUR DATES MAY, JUNE & JULY ALDOUS HARDING http://www.aldousharding.com/ May 18 - Paganini Ballroom, Great Escape, Brighton, UK May 19 - NZ Showcase, The Great Escape, Brighton, UK May 20 - L’Olympic Café, Paris, FRANCE May 21 - Huis 23, Brussels, BELGIUM May 22 - Omeara, London, UK May 23 - Thekla, Bristol, UK May 24 - Eagle Inn, Manchester, UK May 25 - Broadcast, Glasgow, UK May 28 - Schellingwouderkerk, THE NETHERLANDS May 29 - Nochtwache, Hamburg, GERMANY June 3 - Royale, Boston, MA, USA May 30 - Auster Club, Berlin, GERMANY June 6 - Ram’s Head Live, Baltimore, MD, USA June 3 – 4 - Nelsonville Music Festival, OH, USA June 7 - Cat’s Cradle, Carrboro, NC, USA June 5 - DC9, Washington, DC, USA June 8 - Mercury Ballrooom, Louisville, KY, USA June 6 - Johnny Brenda’s, Philadelphia, PA, USA June 9 - Delmar Hall, Saint Louis, MO, USA June 7 - Great Scott, Allston, MA, USA June 11 - Le Divan Orange , Montreal, QC, CANADA DELANEY DAVIDSON http://www.delaneydavidson.com June 12 - Velvet Underground, Toronto, ON, CANADA May 19 - NZ Showcase, The Great Escape, Brighton, UK June 13 - El Club, Detroit, MI, USA May 19 - Harbour Hotel, The Great Escape, Brighton UK June 14 - Empty Bottle, Chicago, IL, USA May 24 - Polka Bar, Munich, GERMANY June 16 - The Earl, Atlanta, GA, USA May 27 - Café Kairo, Bern, SWITZERLAND June 17 - Gasa Gasa, New Orleans, LA, USA June 19 - The Mohawk (Inside), Austin, TX, USA DEVILSKIN http://www.devilskin.co.nz June 20 - The Monarch, El Paso, TX, USA June 6 - The Academy, Dublin, IRELAND June 21 - Hotel Congress, Tucson, -

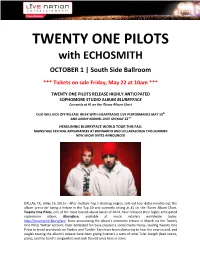

TWENTY ONE PILOTS with ECHOSMITH

TWENTY ONE PILOTS with ECHOSMITH OCTOBER 1 | South Side Ballroom *** Tickets on sale Friday, May 22 at 10am *** TWENTY ONE PILOTS RELEASE HIGHLY ANTICIPATED SOPHOMORE STUDIO ALBUM BLURRYFACE Currently at #1 on the iTunes Album Chart DUO WILL KICK OFF RELEASE WEEK WITH iHEARTRADIO LIVE PERFORMANCE MAY 19th AND JIMMY KIMMEL LIVE! ON MAY 22nd HEADLINING BLURRYFACE WORLD TOUR THIS FALL MAINSTAGE FESTIVAL APPEARANCES AT BONNAROO AND LOLLAPALOOZA THIS SUMMER NEW SHOW DATES ANNOUNCED DALLAS, TX, (May 19, 2015) – After multiple Top 5 charting singles, sold out tour dates months out, the album pre-order being a fixture in the Top 10 and currently sitting at #1 on the iTunes Album Chart, Twenty One Pilots, one of the most buzzed about bands of 2014, have released their highly anticipated sophomore album, Blurryface, available at music retailers worldwide today: http://smarturl.it/blurryface. Since announcing the album’s imminent release in March via the Twenty One Pilots Twitter account, their dedicated fan base created a social media frenzy, leading Twenty One Pilots to trend worldwide on Twitter and Tumblr. Fans have been clamoring to hear the new record, and singles teasing the album’s release have been giving listeners a taste of what Tyler Joseph (lead vocals, piano, and the band’s songwriter) and Josh Dun (drums) have in store. Blurryface takes Twenty One Pilots’ explosive mix of hip-hop, indie rock and punk to the next level, with soaring pop melodies and eclectic sonic landscapes. The fan track, “Fairly Local,” reached #1 on iTunes’ Alternative Chart, and top 5 on Billboard’s Twitter Chart. -

Anuario Ac/E 2016 De Cultura Digital

ANUARIO AC/E 2016 DE CULTURA DIGITAL Cultura inteligente: Impacto de Internet en la creación artística Focus: Uso de nuevas tecnologías digitales en festivales culturales ANUARIO AC/E 2016 DE CULTURA DIGITAL Cultura inteligente: Impacto de Internet en la creación artística Focus: Uso de nuevas tecnologías digitales en festivales culturales Acción Cultural Acción Cultural Española Española www.accioncultural.es Acción Cultural Acción Cultural Española Española www.accioncultural.es Spain’s Public Agency Spain’s Public Agency for Cultural Action for Cultural Action www.accioncultural.es Spain’s Public Agency Spain’s Public Agency for Cultural Action for Cultural Action www.accioncultural.es Merece la pena luchar por una cultura más abierta, igualitaria, participativa y sostenible, pero no es suficiente hacerlo solo con tecnología. Si en en la carrera tecnológica no se tienen en cuenta otros aspectos, el nuevo orden se parecerá cada vez más al viejo, y puede que incluso termine peor. Pero el futuro está aún por decidir. Astra Taylor, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (Metropolitan Books, 2014) Tras la excelente acogida que han tenido las dos y algoritmos inteligentes para obtener valor y primeras ediciones del Anuario AC/E de Cultura sentido de los, a menudo demasiados, y nunca Digital (2014 y 2015), ya que a lo largo de los dos excesivos, datos. Los temas elegidos recorren últimos años se han distribuido más de cinco los caminos de la nueva economía colaborativa; mil ejemplares de ambos estudios, tenemos el analizan su impacto en la creación artística; placer de compartir con los profesionales del exploran un nuevo espacio de conexiones entre sector cultural la tercera edición del Anuario, que personas, máquinas e industrias; y explican los nace con el objetivo de analizar el impacto de las cambios en los mercados y las formas de producir nuevas tecnologías en la creación artística, así y comercializar la obra artística. -

SLRAS Career Highlights

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS November, 2005 – Critically-acclaimed and multi-award winning documentary film Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars premiere’s at prestigious AFI Film Festival in Los Angeles, CA March, 2006 – SLRAS perform at SXSW in Austin, Texas marking their US debut performance June, 2006 – SLRAS perform at Bonnaroo music festival June, 2006 – SLRAS perform at Central Park SummerStage July, 2006 – SLRAS perform at Fuji Rock Festival in Japan September, 2006 – Debut album Living Like a Refugee released on Anti November, 2006 – SLRAS open for Aerosmith in Uncasville, CT December, 2006 – Major motion picture Blood Diamond starring Leonardo DiCaprio and featuring the song “Ankala” by SLRAS released December 15, 2006 – SLRAS appear on the Oprah Winfrey Show June, 2007 - SLRAS collaborate with Aerosmith on “Give Peace A Chance” for Amnesty International’s John Lennon tribute album - Instant Karma January, 2008 - SLRAS invited by United Nations High Commission for Refugees to perform at The World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. April 1, 2008 - U2 tribute album In the Name of Love: Africa Celebrates U2 featuring SLRAS released March 23, 2010 – Second album, Rise & Shine, released on Cumbancha. The album was recorded in New Orleans and produced by Steve Berlin, a member of Los Lobos who has produced for Angélique Kidjo, Michelle Shocked, Jackie Green, Alex Ounsworth, Ozomatli, Rickie Lee Jones and many others. January 2011 - Rise & Shine selected as 2010 Album of the Year on the prestigious World Music Charts Europe. January, 2011 - SLRAS perform on Jam Cruise January, 2011 - CW’s Beverly Hills 90210 features SLRAS song “Respect The Dignity of Women” on episode titled “It’s Getting Hot in Here” May 31, 2011 – SLRAS featured on the song “Gimme Shelter” on Playing for Change 2: Songs Around the World June 4, 2011 – SLRAS open for Dispatch at Red Rocks Amphitheater in Colorado. -

The Economic Impact of Festivals on Small Towns

The Economic Impact of Festivals on Small Towns Gwen Shelton Tennessee Certified Economic Developer Certification Program April 2017 1 Abstract Rural areas have encountered numerous changes to the economic and social fabric of their communities over recent decades. As a result they have suffered declining economies and shifting demographic characteristics, therefore they have looked to tourism and specifically events as foci of rejuvenation. However much of the research in this area has been directed towards the economic impacts of tourism and overlooked the social consequences that tourism and events create. 2 Introduction Background Tourists visit places in search of an interesting environment and plenty of activities they can involve themselves in. There are various activities in the State of Tennessee that tourists can engage in. The State of Tennessee offer tourists a good natural adventure with beauty, music, rivers, and ancient mountains. Whether tourists visit Western, Middle, or Eastern Tennessee’s Regions, they will experience small communities’ festival spirit, camaraderie, and a rich culture rooted in country music, Rock n Roll, culinary delights, shopping, agri-tourism, sports, outdoor recreation, aquariums, museums, and amusement parks for all to enjoy. In addition to the entertainment value, Federal, State and Local Governments rely heavily on tourism for real estate development, tax revenues, and employment generation. Studies are now showing that tourism creates jobs, both through direct employment within the tourism industry and indirectly in sectors such as retail and transportation. When these people spend their wages on goods and services, it leads to what is known as the “multiplier effect,” creating more jobs. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. August 22, 2016 to Sun. August 28, 2016

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. August 22, 2016 to Sun. August 28, 2016 Monday August 22, 2016 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Nothing But Videos Rock Legends Nothing But Videos is a collection of some of the biggest artists today. Catch some of the best Pink Floyd - Pink Floyd, one of the most influential progressive rock bands, released The Dark music videos during this special presentation. Side of the Moon in 1973, which became their most critically and commercially successful album. 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar Rick Steves’ Europe LA Grammy Museum - Sammy explores the Grammy Museum at L.A. Live before being joined London: Historic and Dynamic - In many-faceted London, a visit to the Westminster Abbey, Brit- in the Clive Davis Theater by Nancy Wilson from Heart and Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains. They ish Library, Churchill’s WWII HQ, spend time in Greenwich and experience Soho in the evening. exchange personal stories, followed by an intimate performance. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Rudy Maxa’s World Nothing But Trailers Istanbul, Turkey - Everywhere in the Turkish capital is evidence of civilizations that tried to tame Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! So AXS TV presents Nothing But Trailers. it. From the Romans to the Ottomans, this tumultuous city has seen it all, and its architecture, See the best trailers, old and new, in AXS TV’s collection. -

![Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9839/sadlers-wells-theatre-london-england-fm-mp3-320-124-514-kb-3039839.webp)

Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB

10,000 Maniacs;1988-07-31;Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB 10,000 Maniacs;Eden's Children, The Greek Theatre, Los Angeles, California, USA (SBD)[MP3-224];150 577 KB 10.000 Maniacs;1993-02-17;Berkeley Community Theater, Berkeley, CA (SBD)[FLAC];550 167 KB 10cc;1983-09-30;Ahoy Rotterdam, The Netherlands [FLAC];398 014 KB 10cc;2015-01-24;Billboard Live Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan [MP3-320];173 461 KB 10cc;2015-02-17;Cardiff, Wales (AUD)[FLAC];666 150 KB 16 Horsepower;1998-10-17;Congresgebow, The Hague, Netherlands (AUD)[FLAC];371 885 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-03-23;Eindhoven, Netherlands (Songhunter)[FLAC];514 685 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-07-31;Exzellenzhaus, Sommerbühne, Germany (AUD)[FLAC];477 506 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-08-02;Centralstation, Darmstadt, Germany (SBD)[FLAC];435 646 KB 1975, The;2013-09-08;iTunes Festival, London, England (SBD)[MP3-320];96 369 KB 1975, The;2014-04-13;Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival (SBD)[MP3-320];104 245 KB 1984;(Brian May)[MP3-320];80 253 KB 2 Live Crew;1990-11-17;The Vertigo, Los Angeles, CA (AUD)[MP3-192];79 191 KB 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID BAND;21st Century Schizoid Band;2002-10-01;Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, England [FLAC];619 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID BAND;21st Century Schizoid Band;2004-04-29;The Key Club, Hollywood, CA [MP3-192];174 650 KB 2wo;1998-05-23;Float Right Park, Sommerset, WI;Live Piggyride (SBD)(DVD Audio Rip)[MP3-320];80 795 KB 3 Days Grace;2010-05-22;Crew Stadium , Rock On The Range, Columbus, Ohio, USA [MP3-192];87 645 KB 311;1996-05-26;Millenium Center, Winston-Salem, -

EU Jacksonville

JACKSONVILLE Festival Guide • One Spark • Jax Cocktails • Cummer Garden Month • No Meat March • Hellzapoppin free monthly guide to entertainment & more | march 2014 | eujacksonville.com 2 MARCH 2014 | eu jacksonville monthly contents MARCH 2014 festivals art + theatre page 4-9 local festivals page 26 garden month at the cummer page 10-13 out-of-town festivals page 27 art events and exhibits page 12 festival fashion page 28 theater events page 14 one spark page 29 hellzapoppin page 38 3x5 film festival music on the web life + stuff page 8 katherine archer www.eujacksonville.com page 16 unity plaza update page 30 diablo sez page 17 what’s new page 32-35 music events page 23 life on autopilot eu staff page 24 family events on screen page 25 eco events page 36-37 movies publisher page 25 on the river page 38 mee mee tv William C. Henley managing director Shelley Henley dish page 18 dish update creative director page 19 no meat march on the cover Rachel Best Henley page 20-22 cocktails Photograph by Ryan Smolka from copy editors page 23 what’s brewing Bonnie Thomas Erin Thursby the 2013 Big Ticket Festival. Read Kellie Abrahamson about this year’s Festivals on music editor food editor pages 4-14. Kellie Abrahamson Erin Thursby contributing photographers Richard Abrahamson Ryan Smolka contributing writers Faith Bennett Regina Heffington Kristen Birden Morgan Henley Shannon Blankinship Jen Jones Jon Bosworth Heather Lovejoy Aline Clement Liza Mitchell Brenton Crozier Joanelle Mulrain Jack Diablo Alex Rendon Jennifer Earnest Kristi Lee Schatz Jewel Harrell Madeleine Wagner Published by EU Jacksonville Newspaper.