Caring for Brodsworth : an Impact Study of the 'Conservation in Action' Project at Brodsworth Hall 2016-17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Servants' Passage

SERVANTS’ PASSAGE: Cultural identity in the architecture of service in British and American country houses 1740-1890 2 Volumes Volume 1 of 2 Aimée L Keithan PhD University of York Archaeology March 2020 Abstract Country house domestic service is a ubiquitous phenomenon in eighteenth and nineteenth century Britain and America. Whilst shared architectural and social traditions between the two countries are widely accepted, distinctive cultural identity in servant architecture remains unexplored. This thesis proposes that previously unacknowledged cultural differences between British and American domestic service can be used to rewrite narratives and re-evaluate the significance of servant spaces. It uses the service architecture itself as primary source material, relying on buildings archaeology methodologies to read the physical structures in order to determine phasing. Archival sources are mined for evidence of individuals and household structure, which is then mapped onto the architecture, putting people into their spaces over time. Spatial analysis techniques are employed to reveal a more complex service story, in both British and American houses and within Anglo-American relations. Diverse spatial relationships, building types and circulation channels highlight formerly unrecognised service system variances stemming from unique cultural experiences in areas like race, gender and class. Acknowledging the more nuanced relationship between British and American domestic service restores the cultural identity of country house servants whose lives were not only shaped by, but who themselves helped shape the architecture they inhabited. Additionally, challenging accepted narratives by re-evaluating domestic service stories provides a solid foundation for a more inclusive country house heritage in both nations. This provides new factors on which to value modern use of servant spaces in historic house museums, expanding understanding of their relevance to modern society. -

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

DONCASTER METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE - 7th June 2011 Application 6 Application 11/00712/FUL Application 29th April 2011 Number: Expiry Date: Application Full Application Type: Proposal Erection of 4 detached houses with associated parking and 1 detached Description: bungalow with detached garage on approx. 0.19ha of land, following demolition of existing dwelling (AMENDED NUMBER, TYPE, STYLE AND LAYOUT OF DWELLINGS) At: Hill Crest Barnsley Road Scawsby Doncaster For: Mr Neil Porritt Third Party Reps: 14 Parish: Brodsworth Parish Council Ward: Great North Road Author of Report Teresa Hubery MAIN RECOMMENDATION: GRANT 1.0 Reason for Report 1.1 This application is being presented to committee at the request of Councillor Mordue, also the proposal has received a number of observations in opposition. 2.0 Proposal and Background 2.1 The proposal is for the erection of 4 detached houses with associated parking and 1 detached bungalow with detached garage on approx. 0.19ha of land, a total of 5 dwellings. Initially, the proposal was submitted for the erection of 2 blocks of 3 town houses and 1 detached bungalow; 7 houses. The original proposal has been amended to eliminate concerns from officers and neighbours with regards the highways access, density, type, design, layout and character of dwellings in order that that complement surrounding properties. 2.2 The existing detached dwelling on the site is known as ‘Hill Crest’, Barnsley Road, Scawsby. The dwelling is proposed to be demolished as part of this development and its large garden re-developed. 2.3 The site is situated along Barnsley Road, which is located within the established residential area of Scawsby. -

Conservation Bulletin, Issue 40, March 2001

Conservation Bulletin, Issue 40, March 2001 Gardens and landscape 2 Register of Parks and Gardens 4 Brodsworth Hall 7 Belsay Hall 10 Audley End 12 Contemporary heritage gardens 16 Monuments Protection Programme 20 Historic landscape characterisation 23 Living history 27 Use of peat 30 Grounds for learning 33 Stonehenge: restoration of grassland setting 34 Historic public parks and gardens 37 Earthworks and landscape 40 Wimpole 42 Notes 44 New publications from English Heritage 46 Osborne House: restoration and exhibition 48 (NB: page numbers are those of the original publication) GARDENS & LANDSCAPE Introduction by Kirsty McLeod Gardens and landscape in the care of English Heritage include a wide range of nature conservation areas and historic sites. There have been a number of major garden restorations that have added to the understanding of the past and delighted visitors. Developments in refining historic landscape characterisation, designing contemporary heritage gardens and regenerating public parks have far-reaching implications This issue of Conservation Bulletin focuses on historic gardens and landscape. The Mori Poll undertaken as part of the consultation for the historic environment review shows that people value places, not just as a series of individual sites and buildings but as part of a familiar and much-loved environment – a landscape. As the Black Environment Network has commented in response to the poll: ‘People need to understand the components of their locality – street names, elements of their home, cultural memory, places of worship, green spaces – they all have stories’. It is the whole place, not any individual feature, which speaks to them of their history and which is why we have called the review Power of Place . -

South Yorkshire Countryside Directory for People with Disabilities

South Yorkshire Countryside Directory for People with Disabilities Third Edition Whatever your needs, access to and enjoyment of the countryside is rewarding, healthy and great fun. This directory can help you find out what opportunities are available to you in your area. Get yourself outdoors and enjoy all the benefits that come with it… With a foreword by Lord David Blunkett This directory was designed for people with a disability, though the information included will be useful to everyone. South Yorkshire is a landscape and culture steeped in a history of coal mining, steel industry, agriculture and the slightly more light hearted tradition of butterscotch production in Doncaster! In recent years the major cities and towns have undergone huge transformations but much of the history and industry is still visible today including steel manufacturing in Sheffield, the medieval streets of Rotherham and the weekly town centre market in Barnsley – a tradition held since 1249! For those that enjoy the outdoors, South Yorkshire is equally diverse. You can enjoy the many tracks and trails of the spectacular Peak District National Park or the Trans Pennine Trail, the rolling fields of corn and windmills of Penistone, and the wildfowl delights of Rother Valley Country Park – an opencast coal mine turned local nature reserve. Whatever your chosen form of countryside recreation, whether it’s joining a group, getting out into the countryside on your own, doing voluntary work, or investigating your local wildlife from home, we hope you get as much out of it as we do. There is still some way to go before we have a properly accessible countryside. -

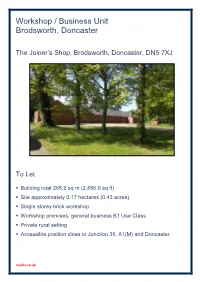

Workshop / Business Unit Brodsworth, Doncaster

Workshop / Business Unit Brodsworth, Doncaster The Joiner’s Shop, Brodsworth, Doncaster, DN5 7XJ To Let . Building total 268.2 sq m (2,886.9 sq ft) . Site approximately 0.17 hectares (0.43 acres) . Single storey brick workshop . Workshop premises, general business B1 Use Class . Private rural setting . Accessible position close to Junction 38, A1(M) and Doncaster savills.co.uk Location The property is situated in the heart of the estate village of Brodsworth, approximately 6 miles north east of Doncaster town centre. The property is well placed for access to the national motorway network with Junction 38 of the A1 (M) situated within two and half miles to the north east, providing links to the north and south of the country. Doncaster station is situated on the East Coast mainline, providing regular rail services to London in under 1 hour 45 minutes. Redhouse Interchange, at Junction 38 of the A1 (M), is one of South Yorkshire’s premier distribution locations with space currently occupied by Next, Asda and B&Q. The town of South Elmsall is approximately 3 miles to the west and is well serviced, providing a range of amenities, including an Asda superstore and Jet petrol station as well as South Elmsall Railway Station. The property lies in a private rural setting immediately north east of Brodsworth Hall well screened to the north by amenity woodland. The surrounding land and property are in the ownership of the landlord with access via a right of way over a shared drive leading south of Home Farm Road and the B6422. -

Heritage Statement Brodsworth Hall Eyecatcher

Heritage Statement Brodsworth Hall Eyecatcher Listed Building Consent for masonry repairs December 2020 Introduction 1. This Heritage Statement has been prepared in support of a Listed Building Consent application for repairs to the Grade II listed Eyecatcher in the grounds of Brodsworth Hall. The Heritage Statement considers the impacts of the proposed works on the building and its setting. Introduction to the site 2. Brodsworth Hall, situated 3km west of Adwick-le-Street and 9km north-west of Doncaster, South Yorkshire, is a late 19th century Grade I listed country house set within a Grade II* registered garden and parkland. The house is Italianate in style and is of a single phase of construction (1861-1863), being built by Charles Sabine Thellusson to replace a demolished 18th century house the site of which is located a short distance to the north. 3. Built from the proceeds of the controversial will of Peter Thellusson who died in 1797, but aimed to control his estate beyond the grave by leaving £700,000 with its accumulated interest to be inherited by the eldest great grandson following the deaths of all intermediate lineal male descendants. The guardianship site forms the core of the much larger Brodsworth Estate and inextricably linked with the Thellusson family who have owned it since the late 18th century. The Eyecatcher 4. The Eyecatcher is situated above the former quarry, elevated high above the Target Range. The Target Range, with the Grove, is c160m long and truncated at the north end by a summer house known as the Target House or Archery Pavilion. -

Notable and Venerable Trees 3

A List of Noteworthy Trees to be found in the Doncaster Borough including some of the largest, oldest and rarest specimens Tree Survey Completed October 2000 “Of all the trees that grow so fair, Old England to adorn greater are none beneath the sun than oak, and ash, and thorn.” From “ A Tree Song” by Rudyard Kipling 1863-1936 Directorate of Development and Transport Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 2 nd Floor, Danum House, St. Sepulchre Gate Doncaster Planning Services DN1 1UB Executive Director: Adam Skinner, B.Arch., R.I.B.A., A.R.I.A.S. April 2001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Council would like to thank the respective owners of trees for their co-operation whilst details were being collected for this document. The council also acknowledge Mrs Spencer for providing historic reference material relating to the Skelbrooke area. The following members of staff contributed to this document: Edwin Pretty (Author) - Planner (Trees) Jonathan Tesh - Planning Assistant (Trees) Colin Howes - Keeper of Environmental Records Julia White - Word Processor Operator Patricia Wood - Word Processor Operator Shirley Gordon - Technician Andrea Suddes - Technician Paul Ramshaw - Technician CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction 1 Geology and Soil Types 1 Hydrology of the Borough 1 What Constitutes a Notable or 2 Venerable Tree Estimated Age of Trees 2 Methodology 2 The List of Notable and Venerable Trees 3 Some Notable Trees of the Past 90 Conclusion 91 Bibliography 92 References 93 APPENDICES Appendix One - Doncaster Landscape Character Areas Appendix Two - Rainfall Figures Appendix Three - Tabulated Statistics of the Trees Listed Appendix Four - Map of Parish Boundaries Appendix Five - Map Showing Site of ‘The Bishops Tree’ GENERAL INTRODUCTION The duties of the author, principally that of administering Tree Preservation Orders and the Hedgerows Regulations, has enabled him to “find” trees which are considered to be noteworthy. -

Doncaster Council Core Strategy 2011-2028

Portrait document = use proportional to the width of each portrait document. Landscape document = use proportional to the height of the document then rotate and position in top left Long and Thin (banner) = use crop marks to 1/3 of the overall length of banner Doncaster Council Core Strategy 2011-2028 Adopted May 2012 Doncaster Local Development Framework www.doncaster.gov.uk Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Chapter 2: Vision and Objectives 13 Chapter 3: Overall Approach 21 Chapter 4: Employment, T own Centres and Transport 39 Chapter 5: Homes and Communities 57 Chapter 6: Attractive, Safe and Healthy Places 69 Chapter 7: Efficient Use of Resources 85 Chapter 8: Implementation 99 Glossary 115 2 Doncaster Council Core Strategy, 2011 - 2028 Contents Policies: Tables: Policy CS1: Quality of Life 22 Table 1: Settlement Hierarchy (Policy CS2) 24 Policy CS2: Growth and Regeneration Strategy 24 Table 2: Broad Locations for Employment Policy CS3: Countryside 33 (Policy CS2) 25 Policy CS4: Flooding and Drainage 35 Table 3: Doncaster’s Output Gap with the Policy CS5: Employment Strategy 41 Yorkshire and Humber Region (2008) 40 Policy CS6: Robin Hood Airport and Table 4: Employment Strategy 41 Business Park 44 Table 5: Housing Phases (Policy CS10) 59 Policy CS7: Retail and Town Centres 47 Table 6: Doncaster’s Aggregates Policy CS8: Doncaster Town Centre 50 (limestone, sand and gravel) 95 Policy CS9: Providing Travel Choice 53 Table 7: Monitoring and Delivery 101 Policy CS10: Housing Requirement, Land Table 8: Infrastructure Delivery Schedule 106 Supply -

Staffing the Big House: Country House Domestic Service in Yorkshire, 1800-1903

i Staffing the Big House: Country House Domestic Service in Yorkshire, 1800-1903 By Carina McDowell Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MA degree in History University of Ottawa © Carina McDowell, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 ii Abstract: Staffing the Big House: Country House Domestic Service in Yorkshire, 1800-1903. Carina McDowell Supervisor: Dr. Béatrice Craig Submitted 2011 This thesis examines domestic service practises among some members of the Yorkshire gentry during the nineteenth century. Historians usually consider the gentry to have shared the same social outlooks and practises as other members of the upper class in spite of significant differences in income and political power. However, as they were less well-to-do, they could not afford to maintain the variety of servants a wealthy aristocrat could. Three main families were selected to reflect the range of incomes and possession or lack thereof of a hereditary title: the Listers of Shibden Hall, the Sykes of Sledmere House and the Pennymans of Ormesby Hall. The Yorkshire gentry organised country houses servants along the same hierarchical lines as prescriptive authors suggested because this gave servants clear paths for promotion which reduced the frequency of staff turnover; furthermore the architecture of their country houses promoted such organization. Secondly, this architecture reinforced the domestic social positions of every rung of the domestic hierarchy. As part of a unique subgroup of the upper class, gentry ladies were less likely to experience class conflict with servants clearly placed within the domestic service hierarchy. The conclusion is that through selective recruitment processes, the distinctive work environment and a particular labour pool, this group created a unique labour market tailored to their social and economic standing. -

Where Are New Homes in Adwick-Le-Street-Woodlands Being Proposed Through the Emerging Doncaster Local Plan?

Where are new homes in Adwick-le-Street-Woodlands being proposed through the emerging How many planning permissions already exist that will contribute towards the Towns’ Doncaster Local Plan? housing need? Some sites have already been built/approved for housing at the settlement as at the base date of the Local Plan (1st April 2015) and will contribute towards Adwick-le-Street-Woodlands’ housing requirement range of 255 - 820 new homes therefore. The largest of these sites (i.e. sites which could provide at least 5+ new homes) are identified as green outline sites on the map and summarised below in Table 1; these sites are proposed to be allocated. National policy states that planning permissions are assumed to be deliverable sites unless clear evidence to the contrary. There are also some smaller sites which have been built over the first 2 years of the plan period (1st April 2015- 31st March 2017) which are also being included in the overall numbers for Adwick- le-Street-Woodlands (but not shown on the map/summary table as they are too small to allocate). In summary, 478 of the 255 - 820 new homes have already been built or have planning permission already granted as at 1st April 2017. How much more housing needs to be identified at Adwick-le-Street-Woodlands? Given the supply of new housing from completions on small sites and existing permissions 5+ units (478 new homes) is above the bottom of the growth range target/requirement, then sufficient housing has been identified, although there is a need to consider whether it is appropriate to allocate towards the top of the growth range at the town which would require land for up to a further 342 new homes. -

Parish and Town Councils Submissions to the Doncaster Council Electoral Review

Parish and Town Councils submissions to the Doncaster Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from Parish and Town Councils. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Click on the submission you would like to view. If you are not taken to that page, please scroll through the document. 31st January 2014 Mr. S. Keal, Review Officer (Doncaster), The Local Government Boundary Commission for England, 3rd Floor, Layden House, 76-86 Turnmill Street, London, EC1M 5LG. Dear Mr. Keal, Electoral Review of Doncaster I thank you for your letter of 26th November 2014, with enclosure in connection with the above, the contents of which were considered by the Parish Council at a meeting held on 28th January 2014. As a result, the Parish Council resolved that representations be made to you requesting that The Local Government Boundary Commission for England, recommends in its current review of warding arrangements for Doncaster, that the Parish of Armthorpe continue as a single Ward as at present. The Parish Council’s reasons for this are as follows:- 1 Number of Electors The electorate figures on the Commission’s website show that for 2013 there are 11,126 electors in Armthorpe and that the electoral forecast for 2019 is 11,232. Armthorpe currently has three ward councillors and on the basis that the Commission is looking for an optimum number of 4,237 electors per councillor, it is self evident that Armthorpe does not qualify to continue as a stand alone Ward, as it would need a total of 12,711 electors. -

Newsletter Spring 2020

Sprotbrough & Cusworth Parish Council News Published by Sprotbrough & Cusworth Parish Council Please recycle Spring 2020 Goldsmith Centre ‘think-tank’ A small ‘think-tank’ of councillors and officers is putting Sprotbrough Road’s Goldsmith Centre under the spotlight. Their aim is to examine the best way forward for the popular community centre, which opened nearly 60 years ago in 1961 and is now showing its age. Parish Chair, Coun David Holland, said: “The building has a large hall and committee room that are open for hire and used by many groups. It’s a real focal point for the local community that we not only want to preserve but also enhance. “We are in fact-finding mode at the moment, considering many options, such as whether the building in its existing form could be modernised. For example, it currently has large areas of flat-roof, which is not a good design feature to have long-term, as we could face costly repairs at some point in Committee room, parish council office and store the future. “The parish council office has also been added to the original design. This is not ideal as the Clerk and Deputy Clerk’s visitors have to access through the committee room, often when meetings are taking place. Current play area “The office is also quite cramped for a parish council of our size, Nursery play area at the rear of the building with no meeting space. Another option under consideration is to look at replacing the Goldsmith Centre with a complete new build. “Nothing has been ruled in or ruled out, we’re currently examining ideas, options and, ultimately, cost.