C:\PSR\Submissions\2002\Accepted 10 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Spain the Reconquista Course Description

Professor Michael A. Furtado 340V McKenzie Hall 346-4834 [email protected] Office Hours: MW 9:00 – 10:00 AM or by appt. HIST 437, Winter 2015 Medieval Spain The Reconquista Course Description The history of Medieval Spain is one of a complex interaction between Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula spanning nearly eight centuries, during which time the various kingdoms of Christian Iberia formed and pressed southward sporadically in what we now refer to as the Reconquista. Indeed, it is quite impossible to understand Medieval Spain without understanding the Reconquista, and one of the primary goals of this class will be to discuss the complex historical issues surrounding this “reconquest”. Over the course of the term we will consider the phenomenon known as the convivencia, the effect of the reconquest on the formation of a “frontier society”, and the complex political relationships between Christian and Muslim political power on the peninsula during the period from 711 to 1492. This will not be a pure lecture survey of Medieval Spanish history. Rather, this course will require engaging the reading actively in weekly discussions, which each student will be required to lead at some point. Rather than examinations, you will write synthetic essays demonstrating your understanding and consideration of the material. Thus, attendance and reading will be critical to your success in the course. Course Objectives Students taking this course will: Learn about the various historical debates concerning the Medieval Iberian Reconquest Demonstrate the ability to read primary sources critically and secondary sources analytically Develop and write effective, supported essays, as well as practice making persuasive oral arguments regarding course themes Engage in comparative thinking designed to stimulate an understanding of the complexity of the Iberian Reconquest and the various roles of economy, religion, and politics in its development Required Reading The following titles are available at the Duckstore. -

The Second Crusade, 1145-49: Damascus, Lisbon and the Wendish Campaigns

The Second Crusade, 1145-49: Damascus, Lisbon and the Wendish Campaigns Abstract: The Second Crusade (1145-49) is thought to have encompassed near simultaneous Christian attacks on Muslim towns and cities in Syria and Iberia and pagan Wend strongholds around the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. The motivations underpinning the attacks on Damascus, Lisbon and – taken collectively – the Wendish strongholds have come in for particular attention. The doomed decision to assault Damascus in 1148 rather than recover Edessa, the capital of the first so-called crusader state, was once thought to be ill-conceived. Historians now believe the city was attacked because Damascus posed a significant threat to the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem when the Second Crusaders arrived in the East. The assault on Lisbon and the Wendish strongholds fell into a long-established pattern of regional, worldly aggression and expansion; therefore, historians tend not to ascribe any spiritual impulses behind the native Christians’ decisions to attack their enemies. Indeed, the siege of Lisbon by an allied force of international crusaders and those of the Portuguese ruler, Afonso Henriques, is perceived primarily as a politico-strategic episode in the on-going Christian-Muslim conflict in Iberia – commonly referred to as the reconquista. The native warrior and commercial elite undoubtedly had various temporal reasons for engaging in warfare in Iberia and the Baltic region between 1147 and 1149, although the article concludes with some notes of caution before clinically construing motivation from behaviour in such instances. On Christmas Eve 1144, Zangī, the Muslim ruler of Aleppo and Mosul, seized the Christian-held city of Edessa in Mesopotamia. -

The Translations of Eça De Queirós'o Suave Milagre, O Defunto

N° Aluno 49337 Images of Portugal between Prestage’s Lines: the Translations of Eça de Queirós’O Suave Milagre, O Defunto,‘A Festa das Crianças’ and ‘Carta VIII- Ao Sr. E. Mollinet’ Sara Lepori Dissertação de Mestrado em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos (Anglo-Portugueses) Orientador: Prof.ª Doutora Gabriela Gândara Terenas May, 2018 [Digitare il testo] . Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Lin- guas, Literaturas e Culturas, Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos (Anglo-Portugueses) realizada sob a orientação científica da Prof.ª Doutora Gabriela Gândara Terenas. [Digitare il testo] Index Introduction........................................................................................................................................................1 1. ‘A Fake Neutrality’: the Relationship Between England and Portugal at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century...................................................................................................................................................3 2.Stereotyping aNation through Translation?..................................................................................................12 3.Prestage and Eça...........................................................................................................................................17 3.1. Edgar Prestage, an English Lusophile....................................................................................17 -

Review of Luis Gorrochategui Santos, the English Armada: the Greatest

Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Journal of the Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Volume 43 Issue 1 Digital Humanities, under the co-editorship of Article 13 Andrea R. Davis & Andrew H. Lee 2018 Review of Luis Gorrochategui Santos, The nE glish Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History José Luis Casabán Institute of Nautical Archaeology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs Recommended Citation Casabán, José Luis (2018) "Review of Luis Gorrochategui Santos, The nE glish Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History," Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies: Vol. 43 : Iss. 1 , Article 13. https://doi.org/10.26431/0739-182X.1297 Available at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs/vol43/iss1/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies by an authorized editor of Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gorrochategui Santos, Luis. The English Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History. Translated by Peter J. Gold. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. viii + 323 pp. + 16 figures + 9 maps. The ill-fated English Armada of 1589 has traditionally received less attention from scholars than the Great Armada that Philip II sent against England in 1588. Both military campaigns have been treated differently from a historiographical point of view; the failure of the Spanish Armada has been idealized and interpreted as the beginning of the end of the Spanish Empire in the Atlantic, and the rise of England as a maritime power. -

Nobel Prize in Literature Winning Authors 2020

NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE WINNING AUTHORS 2020 – Louise Gluck Title: MEADOWLANDS Original Date: 1996 DB 43058 Title: POEMS 1962-2012 Original Date: 2012 DB 79850 Title: TRIUMPH OF ACHILLES Original Date: 1985 BR 06473 Title: WILD IRIS Original Date: 1992 DB 37600 2019 – Olga Tokarczuk Title: DRIVE YOUR PLOW OVER THE BONES OF THE DEAD Original Date: 2009 DB 96156 Title: FLIGHTS Original Date: 2017 DB 92242 2019 – Peter Handke English Titles Title: A sorrow beyond dreams: a life story Original Date: 1975 BRJ 00848 (Request via ILL) German Titles Title: Der kurze Brief zum langen Abschied 10/2017 NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE WINNING AUTHORS Original Date: 1972 BRF 00716 (Request from foreign language collection) 2018 – No prize awarded 2017 – Kazuo Ishiguro Title: BURIED GIANT Original Date: 2015 BR 20746 /DB 80886 Title: NEVER LET ME GO Original Date: 2005 BR 21107 / DB 59667 Title: NOCTURNES: FIVE STORIES OF MUSIC AND NIGHTFALL Original Date: 2009 DB 71863 Title: REMAINS OF THE DAY Original Date: 1989 BR 20842 / DB 30751 Title: UNCONSOLED Original Date: 1995 DB 41420 BARD Title: WHEN WE WERE ORPHANS Original Date: 2000 DB 50876 2016 – Bob Dylan Title: CHRONICLES, VOLUME 1 Original Date: 2004 BR 15792 / DB 59429 BARD 10/2017 NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE WINNING AUTHORS Title: LYRICS, 1962-2001 Original Date: 2004 BR 15916 /DB 60150 BARD 2015 – Svetlana Alexievich (no books in the collection by this author) 2014 – Patrick Modiano Title: DORA BRUDER Original Date: 1999 DB 80920 Title: SUSPENDED SENTENCES: THREE NOVELLAS Original Date: 2014 BR 20705 -

Luso-American Relations, 1941--1951" (2012)

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 2012 Shifting alliances and fairweather friends: Luso- American relations, 1941--1951 Paula Celeste Gomes Noversa. Rioux University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Rioux, Paula Celeste Gomes Noversa., "Shifting alliances and fairweather friends: Luso-American relations, 1941--1951" (2012). Doctoral Dissertations. 674. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/674 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHIFTING ALLIANCES AND FAIRWEATHER FRIENDS: LUSO-AMERICAN RELATIONS, 1941-1951 BY Paula Celeste Gomes Noversa Rioux BA, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, 1989 MA, Providence College, 1997 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History September, 2012 UMI Number: 3533704 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3533704 Published by ProQuest LLC 2012. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

That Hair That Hair

THAT HAIR THAT HAIR translated by Eric M. B. Becker ∏IN HOUSE BOOKS / Portland, Oregon Portuguese Copyright © 2015 Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida e Texto Editores Lda. English Translation Copyright © 2020 Eric M. B. Becker All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Tin House Books, 2617 NW Thurman St., Portland, OR 97210. Published by Tin House Books, Portland, Oregon Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Almeida, Djaimilia Pereira de, 1982- author. | Becker, Eric M. B., translator. Title: That hair / Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida ; translated by Eric M.B. Becker. Other titles: Esse cabelo. English Description: Portland, Oregon : Tin House Books, [2020] | Translated from Portuguese into English. Identifiers: LCCN 2019042836 | ISBN 9781947793415 (paperback) | ISBN 9781947793507 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Almeida, Djaimilia Pereira de, 1982---Fiction. | GSAFD: Autobiographical fiction. Classification: LCC PQ9929.A456 E8613 2020 | DDC 869.3/5--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019042836 First US Edition 2020 Printed in the USA Interior design by Diane Chonette www.tinhouse.com Image Credit (Page 96): Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan, photograph by Will Counts, September 4, 1957. All rights reserved. © Will Counts Collection: Indiana University Archives (http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/archivesphotos/results/item. do?itemId=P0026600). For Humberto Giving thanks for having a country of one’s own is like being grateful for having an arm. How would I write if I were to lose this arm? Writing with a pencil between the teeth is a way of standing on ceremony with ourselves. -

The Saint and the Wry-Neck: Norse Crusaders and the Second Crusade

Pål Berg Svenungsen Chapter 6 The Saint and the Wry-Neck: Norse Crusaders and the Second Crusade During the twelfth century, a Norse tradition developed for participating in the dif- ferent campaigns instigated by the papacy, later known as the crusades.1 This tradi- tion centred on the participation in the crusade campaigns to the Middle East, but not exclusively, as it included crusading activities in or near the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean. By the mid-1150s, the tradition was consolidated by the joint crusade of Earl Rognvald Kolsson of Orkney and the Norwegian magnate and later kingmaker, Erling Ormsson, which followed in the footsteps of the earlier cru- sade of King Sigurd the Crusader in the early 1100s. The participation in the cru- sades not only brought Norse crusaders in direct contact with the most holy places in Christendom, but also the transmission of a wide range – political, religious and cultural – of ideas. One of them was to bring back a piece of the holiness of Jerusalem, by various means, in order to create a Jerusalem in the North. In 1152, a fleet of fifteen large ships from Norway, Orkney and Iceland sailed out from Orkney towards the Holy Land.2 The fleet, commanded by the earl and later saint of Orkney, Rognvald Kali Kolsson (r.1136–1158), and the Norwegian “landed man” [lenðir 1 For a general overview of the development of the crusades, see Jonathan Riley-Smith, What Were the Crusades?, fourth ed. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Norman Housley, Fighting for the Cross: Crusading to the Holy Land (New Haven–London: Yale University Press, 2008); Christopher Tyerman, God’s War: A New History of the Crusades (Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006). -

The Battle of Las Navas De Tolosa: the Culture and Practice of Crusading in Medieval Iberia

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2011 The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa: The Culture and Practice of Crusading in Medieval Iberia Miguel Dolan Gomez [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Gomez, Miguel Dolan, "The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa: The Culture and Practice of Crusading in Medieval Iberia. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1079 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Miguel Dolan Gomez entitled "The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa: The Culture and Practice of Crusading in Medieval Iberia." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Thomas E. Burman, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jay Rubenstein, Chad Black, Maura Lafferty Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa: The Culture and Practice of Crusading in Medieval Iberia A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Miguel Dolan Gomez August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Miguel D. -

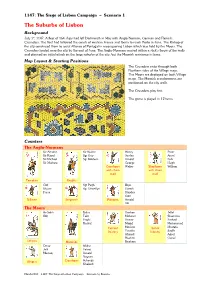

The Suburbs of Lisbon Background July 1St, 1147: a Fleet of 164 Ships Had Left Dartmouth in May with Anglo-Norman, German and Flemish Crusaders

1147: The Siege of Lisbon Campaign – Scenario 1 The Suburbs of Lisbon Background July 1st, 1147: A fleet of 164 ships had left Dartmouth in May with Anglo-Norman, German and Flemish Crusaders. The fleet had followed the coasts of western France and Iberia to reach Porto in June. The Bishop of the city convinced them to assist Alfonso of Portugal in reconquering Lisbon which was held by the Moors. The Crusaders landed near the city by the end of June. The Anglo-Normans moved within a stick’s throw of the walls and planned an initial attack on the large suburbs of the city, but the Moorish resistance is fierce. Map Layout & Starting Positions The Crusaders enter through both Northern sides of the Village maps. The Moors are deployed on both Village maps. The Moorish crossbowmen are positioned on the city walls. The Crusaders play first. The game is played in 12 turns. Counters The Anglo-Normans Sir Amalric Sir Walter Henry Peter Sir Raoul Sgt Guy Jordan Ansel Sit Michael Sgt Baldwin Arnold Fulk Sir Mathew George Hugh Crossbows Walter Shortbows William with chain with chain mail mail Templars Knights Cliff Sgt Pugh Bryn Shawn Sgt Llewellyn Gareth Fursa Hayden Stori Billmen Sergeants Pikemen Arnold Aki The Moors As-Salih Baha Gashan Jellal Kilij Taki Mehmet Shammin Yaghi Anwar Farhad Rashid Magid Mohammad Fatimid Moshen Seljuk Mustafa Infantry Yasaffa Infantry Sadik Ahmed Ageel Hashmi Osewl Officers Mamluks Ibraham Omar Abdur Jalil Fahrat Mustaq Junaid Nayeen Slingers Crossbows Jehangir Khaleed March 2010 – 1147: The Siege of Lisbon Campaign – Scenario by Buxeria 1147: The Siege of Lisbon Campaign – Scenario 1 Victory Conditions The Crusaders have to conquer both Village maps. -

Reading List

SPAIN & PORTUGAL Reading List GENERAL BACKGROUND Eyewitness Travel Guide Portugal with Madeira & the Azores, Eyewitness Guides. A compact, visual travel guide to the country featuring hundreds of photographs and drawings, an excellent overview of the culture and history of Portugal, and good information about where to go and what to do. With many excellent regional, local and neighborhood maps. A Traveler's History of Portugal, Robertson, Ian. A lively, admirably concise survey from prehistory to the present. The author has also written the Blue Guides to both Portugal and Spain. Eyewitness Guide to Madrid (Dorling Kindersley). The Regions of Spain: A Reference Guide to History and Culture, Kern, Robert. Greenwood Press. Basque History of the World, Kurlansky, Mark. Penguin. An American writer's study of life in the Basque Country, from the origins of the Basque people to their search for an identity in modern Europe. The New Spaniards, Hooper, John. Penguin. Fascinating and readable chronicle of the making of modern Spain by British journalist Hooper, who was a foreign correspondent in Madrid during the key years of the transition. South from Granada, Brenan, Gerald . Kodansha. The British author's account of life in a Spanish pueblo in the 1920s is still a classic and an inspiration for thousands who have moved to Spain. Franco, Preston, Paul. A comprehensive biography of Spain's 20th-century dictator. Madrid, Nash, Elizabeth. An informative, entertaining and joyfully written account of the city. HISTORY Homage to Catalonia, Orwell, George. Harvest Books. Orwell's poignant account of his involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Malaga Burning, Woolsey, Gamel. -

Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo EXPLAINING DIVINE PROVIDENCE

Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo EXPLAINING DIVINE PROVIDENCE: VIRTUES, VICES, AND THE BIBLE IN THE NARRATIVES OF THE SECOND CRUSADE MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2018 EXPLAINING DIVINE PROVIDENCE: VIRTUES, VICES AND THE BIBLE IN THE NARRATIVES OF THE SECOND CRUSADE by Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo (Colombia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 EXPLAINING DIVINE PROVIDENCE: VIRTUES, VICES AND THE BIBLE IN THE NARRATIVES OF THE SECOND CRUSADE by Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo (Colombia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 EXPLAINING DIVINE PROVIDENCE: VIRTUES, VICES AND THE BIBLE IN THE NARRATIVES OF THE SECOND CRUSADE by Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo (Colombia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies,