Effect of the Two-Party System on Voter Turnout in the United States of America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voter Turnout in Texas: Can It Be Higher?

Voter Turnout in Texas: Can It Be Higher? JAMES MCKENZIE Texas Lyceum Fellow WHAT’S THE TAKEAWAY? In the 2016 presidential election, Texas’ voter turnout Texas’ voter turnout is among placed near the bottom of all the states, ranking 47th. In the lowest in the nation. Texas’ recent 2018 mid-term election, which featured a Low turnout can lead to policies closely contested US Senate race and concurrent favoring the interests of gubernatorial election, not even half of eligible voters demographic groups whose (46.3%) participated.1 members are more likely to vote. Low voter turnout is not a recent phenomenon in Texas. Tex- There are deterrents to as has consistently lagged the national average in presidential registering and voting that the elections for voter turnout among the voting eligible popula- state can address. tion (VEP). In fact, since 2000, the gap between Texas’ turn- out and the national average consecutively widened in all but Policies such as same-day registration, automatic voter one election cycle.2 Texans may be open to changes to address registration, mail-in early voting, low turnout. According to a 2019 poll by the Texas Lyceum on and Election Day voting centers Texans’ attitudes toward democracy, a majority (61%) agreed could help. that “significant changes” are needed to make our electoral system work for current times.3 VOLUME 10 | ISSUE 6 | SEPTEMBER 2019 2 DOES VOTER TURNOUT MATTER? This report addresses ways to boost voter Voter turnout is often considered the curren- participation in both population sets. cy of democracy, a way for citizen’s prefer- ences to be expressed. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 17-1200 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- INDEPENDENT PARTY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. ALEX PADILLA, CALIFORNIA SECRETARY OF STATE, Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF CITIZENS IN CHARGE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PAUL A. ROSSI Counsel of Record 316 Hill Street Mountville, PA 17554 (717) 961-8978 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the party names INDEPENDENT PARTY and AMERICAN INDEPENDENT PARTY are so sim- ilar to each other that voters will be misled if both of them appeared on the same California ballot. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ............................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 3 CONCLUSION .................................................... -

Is It Unity They Want, Or Capitulation? by Steve Bakke December 18, 2020

If you don’t regularly receive my reports, request a free subscription at [email protected] ! Follow me on Twitter at http://twitter.com/@BakkeSteve and receive links to my posts and more! Visit my website at http://www.myslantonthings.com ! Is it unity they want, or capitulation? By Steve Bakke December 18, 2020 “It’s time to put the anger and harsh rhetoric behind us and come together as a nation……I pledge to be a president who seeks not to divide but unify……to unite us here at home.” That’s Joe Biden proclaiming unity soon after election day. I’ll again express my concern that this was probably more of a warning than a peace offering. Before I conclude on that speculation let’s look at what others of his flock have been saying lately. Are they friendly and inviting? Do they feel warm and fuzzy? Most quotes are from after election day. Hold on to your seat! • ‘We don’t do things like those chumps out there with the microphones, those Trump guys.” – Joe Biden himself speaking at a small gathering of supporters. • “Hang your head in shame.” – CNN’s Don Lemon addressing republican legislators who supported Trump’s efforts to get the Supreme Court to review constitutional issues regarding the election. • “It’s not enough to just send Donald Trump packing, or even just to repair the damage he’s done. We’ve got to unrig and rebuild the systems that made his rise possible…” – Elizabeth Warren. • ‘I used to wonder how could the people of Germany allow Hitler to exist. -

Active Political Parties in Village Elections

YEAR ACTIVE POLITICAL PARTIES IN VILLAGE ELECTIONS 1894 1895 1896 1897 Workingman’s Party People’s Party 1898 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1899 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1900 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1901 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1902 Citizen’s Party Reform Party Independent Party 1903 Citizen’s Party Independent Party 1904 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1905 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1906 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1907 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1908 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1909 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1910 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1911 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1912 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1913 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1914 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1915 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1916 Citizen’s Party Independent Party American Party 1917 Citizen’s Party American Party 1918 Citizen’s Party American Party 1919 Citizen’s Party American Party 1920 Citizen’s Party American Party 1921 Citizen’s Party American Party 1922 Citizen’s Party American Party 1923 Citizen’s Party American Party 1924 Citizen’s Party American Party Independent Party 1925 Citizen’s Party American party 1926 Citizen’s party American Party 1927 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1928 Citizen’s Party American Party 1929 Citizen’s Party American Party 1930 Citizen’s Party American Party 1931 Citizen’s Party American Party 1932 Citizen’s Party American Party 1933 Citizen’s Party American Party 1934 Citizen’s Party American Party 1935 Citizen’s Party American Party 1936 Citizen’s Party Old Citizen’s -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

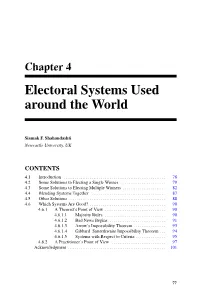

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Voting Alone: The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/50p7t4xg Author Guenther, Scott Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Voting Alone: The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Scott M. Guenther Committee in charge: Professor James Fowler, Chair Professor Samuel Kernell, Co-Chair Professor Julie Cullen Professor Seth Hill Professor Thad Kousser 2016 Copyright Scott M. Guenther, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Scott M. Guenther is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To my parents. iv EPIGRAPH Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead. { Benjamin Franklin v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................... iii Dedication...................................... iv Epigraph......................................v Table of Contents.................................. vi List of Figures................................... viii List of Tables.................................... ix Acknowledgements.................................x Vita........................................ -

The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout - and What We Can Do About It

IHS Political Science Series Working Paper 54 February 1998 The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout - and What We Can Do About It Arend Lijphart Impressum Author(s): Arend Lijphart Title: The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout - and What We Can Do About It ISSN: Unspecified 1998 Institut für Höhere Studien - Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) Josefstädter Straße 39, A-1080 Wien E-Mail: offi [email protected] Web: ww w .ihs.ac. a t All IHS Working Papers are available online: http://irihs. ihs. ac.at/view/ihs_series/ This paper is available for download without charge at: http://irihs.ihs.ac.at/1045/ Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 54 The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout – and What We Can Do About It Arend Lijphart 2 — Arend Lijphart / The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout — I H S The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout – and What We Can Do About It Arend Lijphart Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 54 February 1998 Prof. Dr. Arend Lijphart Department of Political Science, 0521 University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California 92093–0521 USA e-mail: [email protected] Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Arend Lijphart / The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. -

Republican Women and the Gendered Politics of Partisanship

Melanie Susan Gustafson. Women and the Republican Party, 1854-1924. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001. ix + 288 pp. $34.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-252-02688-1. Reviewed by Linda Van Ingen Published on H-Women (June, 2002) Republican Women and the Gendered Politics tions of party politics. In other words, disfran‐ of Partisanship, 1854-1924 chised women were both partisan and nonparti‐ Melanie Gustafson successfully confronts the san players who sought access to the male-domi‐ historical complexity of American women's parti‐ nated institutions of political parties without los‐ sanship in Women and the Republican Party, ing their influence as women uncorrupted by 1854-1924. Her work deepens and enriches the such politics. The resulting portrait of women's field of women's political history in the late nine‐ political history, then, is more complex than pre‐ teenth and early twentieth centuries by bringing viously realized. This book demonstrates how together two seemingly disparate trends in wom‐ much of women's political history is about the en's politics. On the one hand, historians have gendered politics of partisanship. long focused on women's nonpartisan identities in Gustafson develops her analyses with a focus their altruistic reform and suffrage movements. on the Republican Party at the national level. Politics in these studies has been defined broadly From its founding in 1854, through the Progres‐ to include the wide range of women's public activ‐ sive Party challenge in the early twentieth centu‐ ities and the formation of a women's political cul‐ ry, to the height of its success in the 1920s, the Re‐ ture.[1] On the other hand, historians have more publican Party provides a chronological history recently studied women's partisan loyalties and that holds Gustafson's study of women's varied their roles in institutional politics. -

Russia by Robert W

Russia by Robert W. Orttung Capital: Moscow Population: 142.0 million GNI/capita: US$15,460 Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Bank Indicators 2010. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Electoral Process 4.25 4.50 4.75 5.50 6.00 6.25 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 Civil Society 4.00 4.00 4.25 4.50 4.75 5.00 5.25 5.50 5.75 5.75 Independent Media 5.25 5.50 5.50 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 Governance* 5.00 5.25 5.00 5.25 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 6.50 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 4.50 4.75 4.50 4.75 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.50 5.50 Corruption 6.25 6.00 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 Democracy Score 4.88 5.00 4.96 5.25 5.61 5.75 5.86 5.96 6.11 6.14 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Evaluating the Impact of Drop Boxes on Voter Turnout

Evaluating the Impact of Drop Boxes on Voter Turnout William McGuire, University of Washington Tacoma Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien, San Diego State University Katherine Baird, University of Washington Tacoma Benjamin Corbett, Lawrence Livermore Lab Loren Collingwood, University of California Riverside Voter turnout in the United States lags behind most other developed democracies. A popular approach for increasing turnout is to improve the ease of voting. While evidence indicates that vote by mail (VBM) requirements increase voter turnout, there is little evidence of the impact ballot drop boxes have on voting, despite the fact that voters in VBM states often prefer these boxes to voting via the postal service. All VBM states (currently Washington, Colorado and Oregon) require some provision for voting by drop boxes. This project examines the impact the installation of new ballot drop boxes had on voter turnout in Pierce County, the second largest county in Washington State. To identify the causal effects of these boxes on the decision to vote, we exploit the randomized placement of five new ballot drop boxes in Pierce prior to the 2017 general election. Voters selected to receive a new ballot drop box experienced an average reduction in distance to their nearest drop box of 1.31 miles. We estimate that this change in proximity to drop boxes increased voter turnout. Specifically, we find overall a 0.64 percentage point increase in voting per mile of distance to nearest drop box reduced. The effect, hence, is not a particularly large one. However, within the context of the very low turnout in Pierce County in 2017 and compared with alternative ways election officials have attempted to encourage more people to vote, this effect is not negligible. -

Minority Governments and Party Politics: the Political and Institutional Background to the “Danish Miracle”

Minority Governments and Party Politics: The Political and Institutional Background to the “Danish Miracle” Christoffer Green-Pedersen 01/1 Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung Paulstrasse 3 50676 Köln Germany Telephone 02 21/27 67 - 0 Fax 0221/2767-555 MPIfG Discussion Paper 01/1 E-Mail [email protected] ISSN 0944–2073 Home Page http://www.mpi-fg-koeln.mpg.de March 2001 Green-Pedersen: Political and Institutional Background to the “Danish Miracle” 2 Abstract The performance of the Danish economy in the 1990s has been successful to the extent that scholars are talking about a “Danish miracle”. The importance of gov- ernment policies to Denmark’s economic success is taken as a point of departure in investigating why Danish governments have been able to govern the economy successfully in the 1990s. The paper argues that two factors have been important. First, the functioning of Danish parliamentarianism has been reshaped to strengthen the bargaining position of minority governments, which became the rule in Danish politics after the landslide election in 1973. Today, Danish minor- ity governments can enter agreements with changing coalitions in the Danish parliament. The paper thus challenges the conventional wisdom about minority governments as weak in terms of governing capacity. Second, the changed socio- economic strategy of the Social Democrats after returning to power in 1993 has been important because it has created a political consensus around a number of controversial reforms. Zusammenfassung Der Erfolg der dänischen Wirtschaft in den 90er Jahren lässt Fachleute von einem „dänischen Wunder“ sprechen. Die große Bedeutung der Regierungspolitik für den wirtschaftlichen Erfolg Dänemarks dient als Ausgangspunkt für eine Unter- suchung der Bestimmungsfaktoren der erfolgreichen Wirtschaftspolitik däni- scher Regierungen in den 90er Jahren.