COMMUNITY COLLEGES and the ACCESS EFFECT This Page Intentionally Left Blank Community Colleges and the Access Effect Why Open Admissions Suppresses Achievement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Curriculum Leadership Capacity-Building Through Biographical Narrative: a Currere Case Study

EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Karl W. Martin August 2018 © Copyright, 2018 by Karl W. Martin All Rights Reserved ii MARTIN, KARL W., Ph.D., August 2018 Education, Health and Human Services EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY (473 pp.) My dissertation joins a vibrant conversation with James G. Henderson and colleagues, curriculum workers involved with leadership envisioned and embodied in his Collegial Curriculum Leadership Process (CCLP). Their work, “embedded in dynamic, open-ended folding, is a recursive, multiphased process supporting educators with a particular vocational calling” (Henderson, 2017). The four key Deleuzian “folds” of the process explore “awakening” to become lead professionals for democratic ways of living, cultivating repertoires for a diversified, holistic pedagogy, engaging in critical self- examinations and critically appraising their professional artistry. In “reactivating” the lived experiences, scholarship, writing and vocational calling of a brilliant Greek and Latin scholar named Marya Barlowski, meanings will be constructed as engendered through biographical narrative and currere case study. Grounded in the curriculum leadership “map,” she represents an allegorical presence in the narrative. Allegory has always been connected to awakening, and awakening is a precursor for capacity-building. The research design (the precise way in which to study this ‘problem’) will be a combination of historical narrative and currere. This collecting and constructing of Her story speaks to how the vision of leadership isn’t completely new – threads of it are tied to the past. -

Prisoners of Our Thoughts

Praise for PRISONERS OF OUR THOUGHTS “In this newly revised edition, Alex Pattakos and Elaine Dundon not only honor the legacy of Viktor Frankl, but they also further it by bringing his work to a new generation of readers in search of a more meaningful life. In very practical ways, they show that when we put meaning at the heart of our lives, we’re better able to thrive and reach our full potential.” — Arianna Huffington, founder ofThe Huffington Post and founder and CEO of Thrive Global “If you intend to read just one self-help book in your life, pick this one. You won’t regret it.” — Alexander Batthyany, PhD, Director, Viktor Frankl Institute, Vienna, Austria “Here is a landmark book that, among other things, underscores how the search for meaning is intimately related to and positively influences health improvement at all levels. Reading Prisoners of Our Thoughts is an insightful prescription for promoting health and wellness!” — Kenneth R. Pelletier, PhD, MD (hc), Clinical Professor of Medicine and Professor of Public Health, University of Arizona and University of California, San Francisco Schools of Medicine “Prisoners of Our Thoughts is an important book about creating a meaningful life— a life that matters and makes a difference. Those of us involved in the individual quest for meaning will find valuable information and inspiration in it. Meaning— choosing it, living it, sustaining it— is a significant personal, as well as societal, issue of the twenty-first century.” — Marita J. Wesely, Trends Expert and Trends Group Manager, Hallmark Cards, Inc. “This book is a gem. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

Demographics of the Sample

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Steering an AIDS-free Course: Personal Prevention Strategies of Young People in Tanzania being a Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Laurie Lynn Kelly, BSc, MF, PG Dip (Research) September 2012 Abstract This thesis presents an exploration of the personal HIV/AIDS prevention strategies of young adolescents in Tanzania. Most of the 209 research participants were aged 10- 15. They included students, those out of school and ‘street children’. In this multiple method study, the young people participated in focus groups, individual interviews, questionnaires, ranking exercises, and write-and-draw exercises. Most of the participants were motivated to prevent HIV/AIDS and were able to communicate credible strategies. Many participants described tactics related to refraining from sex. Males tended to describe sexual temptation in terms of their own sexual desires, and refraining from sex in terms of the management of those desires. Females tended to describe sexual temptation in terms of the benefits males might offer in exchange for sex and the possible risks of agreement or refusal. Females described refraining from sex in terms of politely refusing, eluding and outsmarting males, and avoiding situations where rape might occur. Male participants who discussed penile-anal sex nevertheless seemed to associate HIV transmission mainly with heterosexual relationships and penile-vaginal sex. In further findings, many participants described tactics related to the prevention of blood-borne infection. Some participants mentioned testing and transmission in mother-to-child and caring relationships. Although most participants agreed in theory that condoms were a good way to prevent HIV/AIDS and that it was acceptable for a male or female to ask a partner to take an HIV test before having sex, relatively few participants included testing or condoms in their strategies. -

Encyclopedia of Beat Literature

L i t erary Moven1ents..R"• ENCYCLOPEDIA OF BEAT LITERATURE THii ESSENTIAL GU I DE TO Tlil3 L l\' l~ S AND \VORK S 0" THE BEAT WRITERS-jA C ~ K EROUAC, ALLEN G I NSBURG, \VJLLIAM B URROUGH S. AND MANY MORE KLl l\.T H ENI NI ER. Encyclopedia of Beat Literature Edited by Kurt HEmmEr Foreword by Ann cHArtErs Afterword by tim Hunt Photographs by LArry KEEnAn Encyclopedia of Beat Literature Copyright © 2007 by Kurt Hemmer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permis- sion in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York, NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of beat literature / edited by Kurt Hemmer; foreword by Ann Charters; afterword by Tim Hunt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4297-7 (alk. paper) 1. American literature—20th century—Encyclopedias. 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography—Encyclopedias. 3. Beat Generation— Encyclopedias. I. Hemmer, Kurt. PS228.B6E53 2006 810.9′11—dc22 2005032926 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. -

Submitted By: Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar

Naturally changing Trance as our natural changing mode - reforming and naturalising trancework Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar AMT's GHR LNCP LHS LCPS Adv.Dip.Prof.SM Abstract The major controversial themes, for theoreticians as well as for clinical hypnotherapists are less about practical applications of hypnosis and more about the nature of trance, the nature of hypnosis. This article will present trance as a natural change-mode, the capacity for flexibility of our reality-mode. Trance is the process whereupon our flexibility is enhanced and our susceptibility to internal changes is heightened. Trance will be explained as the prerequisite state for any internal change that we make throughout our lives. When trance is established as a generic phenomenon, hypnotherapy would be defined as a professional facilitation of a natural change mode, and the concept of hypnotisability will no longer be needed. Content 1. Introduction 2. Formative theories about trance and hypnosis: I - The Neo-Dissociation theory - Ernest Hilgard II - Milton Erickson III - NLP IV - Trancework - Michael Yapko V - The System/Mathematical model - Dylan Morgan VI - Body-mind Influences 3. Trance - our natural changing mode I - Introduction and Definition II - Flexibility, Change and Trance III Subconscious resources IV Naturalising trance V Therapeutics VI Summary 4. Conclusion 1. Introduction The debate about hypnosis is less focused on the practicality of applying it - although methods of trancework vary, the major controversial themes are about the nature of trance, the nature of hypnosis. Defining trace or hypnosis is a slippery task. There are numerous theories, explaining the way hypnosis works, possibly as many as there are hypnotherapists, and then some more. -

Supporting Farming Communities at Times of Uncertainty an Action Framework to Support the Mental Health and Well-Being of Farmers and Their Families

Supporting farming communities at times of uncertainty An action framework to support the mental health and well-being of farmers and their families Alisha R. Davies, Lucia Homolova, Charlotte N.B. Grey, Jackie Fisher, Nicole Burchett, Antonis Kousoulis Supporting farming communities at times of uncertainty An action framework to support the mental health and well-being of farmers and their families Authors Alisha R. Davies1, Lucia Homolova1, Charlotte N.B. Grey1, Jackie Fisher2, Nicole Burchett2, Antonis Kousoulis2 Affiliations 1. Research and Evaluation Division, Knowledge Directorate, Public Health Wales; 2. Mental Health Foundation Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following for their valuable insights into supporting farmers and farming communities in times of uncertainty: Name Organisation (listed alphabetically) Anne Thomas, Outpatient Nurse; Dolgellau Farming Initiative Lead Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board Iwan Jones, Engagement Officer Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board Megan Vickery, Engagement Officer Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board Emma Picton-Jones, Chief Executive DPJ Foundation Emma Morgan, Volunteer DPJ Foundation David Williams, Wales Regional Director Farming Community Network Nia Williams, Farming family member Farming Family member Sara Jenkins, Development Manager for Farming Connect Menter a Busnes; Farming Connect Contracts Mary Griffiths, Development Manager Mid Powys Mind Charlotte Hughes, Wales Programme Manager Mind Cymru Dylan Morgan, Deputy Director/ Head of Policy National Farmers -

Towards a New NLP

Towards a New NLP Mohammed Tikrity March 2004 Introduction NLP astonishes thousands of people with big success stories and amazing results for those who use it. NLP improves people’s communication, decision making, time management, presentation skills, negotiation skills, sales results, team building, coaching and personal success. The Science Digest considers NLP as “the most important synthesis of knowledge about communications to emerge since the'60's”. NLP is taught and practised everywhere over the globe. Even NASA starts using NLP. NLP Comprehensive published an interview with Dr. Alenka Brown Vanhoozer, Director for Advanced Cognitive Technologies by Al Wadleigh under the title “NASA Launches with NLP!” Al Wadleigh said that “Dr Alenka is taking NLP to the stars… her work involves using NLP to create what she calls Adaptive Human-System Integration Technologies for various applications: aerospace (commercial, military, NASA), brain mapping, behaviour profiling, modelling of learning and decision-making strategies and more .” But despite all this success NLP has received serious criticism from many researchers, psychologists and writers. There is no doubt, that NLP has been misunderstood, misused and abused. So, where does NLP stands and where is it going? The Strength of NLP is its weakness at the same time. NLP relies on subjective experience and follows a pragmatic philosophy. In other word there is a distance between NLP and science. This distance makes NLP a “soft” discipline which leads into questioning the reliability of NLP. On the other hand, if NLP follows the “scientific methods” it will loose its power. It seems that the only escape for NLP is to consider it as an art rather than science, and an engineering practices rather than theoretical investigation. -

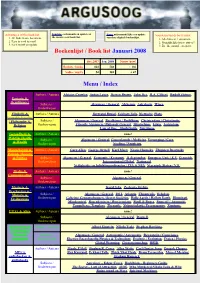

Argusoog Bibliotheek

Advantages of this book list: Send me each month an update of Stuur mij maandelijks een update Voordelen van de boekenlijst: the most recent book list. van deze digitale boekenlijst. 1. All links in one document. 1. Alle links in 1 document. 2. Easy to send by mail! 2. Gemakkelijk door te sturen!! 3. Each month an update. 3. En elke maand een update. Boekenlijst / Book list Januari 2008 Dec.2007 Jan. 2008 Nieuw /new! Boeken / books 424 560 + 136 Audio / mp3’s 54 101 + 47 Menu / Index Authors / Auteurs Aleister Crowley, Anton Lavey, Derren Brown, John Dee, R.A. Gilbert, Rudolf Steiner, Esoterie & Occultism(e) Subjects / Algemeen / G eneral , Alchemie, Astrologie, Wicca, Onderwerpen FiloSofie & Authors / Auteurs Bertrand Russel, Eckhart Tolle, Nietzsche, Plato, Levensbeschouwing / Philosophy & Subjects / Algemeen / General, Boedhisme / Buddhism, Christendom / Christianity, Religion Onderwerpen Filosofie Algemeen / Philosofy General, Hindoeïsme, Islam, Jodendom, Law of One – StudyGuide, Spiritisme, Gezondheid & Authors / Auteurs none! Welzijn, Health Subjects / Algemeen / General, Geneeskunde / Medicine, Verzorging / Care, & Wealth Onderwerpen Voeding / Nutricion, Maatschappij & Authors / Auteurs Gary Allen, George Orwell, Karl Marx, Noam Chomsky, Zbigniew Brezinski, Politiek / Society & Politics Subjects / Algemeen / General, Economie / Economy, 11 September, Europese Unie / E.U, Genocide, Onderwerpen Internationaal/Global, Nationaal, Veiligheids- en Inlichtingendiensten / CIA & NSA, Verenigde Staten / V.S., Media & Authors / Auteurs none! -

Archived News

Archived News 2009-2010 News articles from 2009-2010 Table of Contents Jane Alexander ’61 ........................................... 10 David Lindsay-Abaire ’92................................ 30 New book by economics faculty member Jamee Tessa Corthell ’07............................................. 30 Moudud calls into question neoliberal theory and Undercovers, the latest series from writer- policies ............................................................. 11 producer-director J.J. Abrams '88, picked up by Alumni achievement and service award winners NBC for fall season .......................................... 30 represent outstanding accomplishment in Pam Tanowitz MFA '98 and Anne Lentz '98 ... 30 education, broadcasting, law, and the arts ........ 12 Sarah Lawrence College................................... 31 History faculty member Fawaz Gerges named inaugural director of The London School of Photographer Alec Soth '92 chronicles his travels Economics and Political Science's Middle East around America in video series for The New York Centre................................................................ 14 Times..................................................................31 Zoe Alexander '13 designs and produces first- Variety profiles director Sanaa Hamri '96 in ever plantable high-fashion coat in Biomimicry advance of her latest motion picture release..... 31 Project ............................................................... 14 Celebrating Oxford: Reflections on the Sarah Alumna Julianna Margulies tells Class -

2020 Commencement Book

The 135th Commencement Commencement I offer my warmest congratulations to our Congratulations to the Class of 2020! graduates! You have achieved an important milestone — You have worked diligently to get to this you earned your RIT degree! moment. You, the Class of 2020, completed your rigorous course work and research at RIT, You will be remembered for your strength and during a pandemic. resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. We are all very proud of you! Today’s world needs people who know how to create and innovate, analyze and implement, collaborate and lead. On behalf of the faculty and staff, thank you for giving us the You, the Class of 2020, are those people. opportunity to be your teachers, mentors, and friends. Completing your degree marks not just an end; it is also a beginning. You are ready to embark on the next chapter of your life and career. Upon leaving RIT, you will have opportunities for lifelong learning and As you leave RIT, we urge you to stay curious and socially conscious. achieving new goals. Many of you will immediately enter productive Added to the foundation of your RIT education, this mindset will help careers, while others may go on to further your education. you continue to shape the future wherever you go. We hope when you reflect on your time at RIT, your memories will be We look forward to maintaining a close relationship, as you are now of favorite professors and staff, lasting friendships, and a feeling of RIT for Life. Please keep in touch and let us know how we can continue pride and fulfillment. -

1994 Yearbook

g^:~?~**~ ;x--tt *+ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/ui1994univ University High School 1993-94 1212 West Springfield Urbana, II 61801 217-333-2870 Interim Principal Barbara Wysocki . TABLE OF CONTENTS. STUDENT LIFE 4 SEPTErmER ORGANIZATIONS 16 PI ^ V SPORTS 34 4>\ FACULTY 52 IHTTiniET! A I* IE TT. UNDERCLASSMEN 66 SENIORS 96 ADS & INDEX 128 HOYEriHEK n a im: h CLOSING 142 nxMHuiinti a^nui^ivi Every year has its own atmosphere; this one was full of changes. The faculty was in a state of flux, and was reorganized at various points in the year. The computer lab was updated to give all students and faculty E- mail accounts and to organize Agora Days. Also the subbies went to the first Subbie Retreat in our history. Over all, the year was a whirlwind of changes. Amid the changing seasons, Uni students didn't lose themselves in the shuffle. Students were thrilled that the dramatic weather gave them extra time off from school. At the beginning of the year due to high humidity and temperatures, several days were shortened. The third week after winter break the school was closed for two days because of extremely cold weather. They still had time to enjoy themselves. With the computerization of our grapevine, gossip abounded and school spirit grew. Agora Days was a success, but new regulations imposed by the State left students searching for classes to fill the 300 minute rule. The finals schedule was also affected by the 300 minute rule.