Instant Replay Article Preliminary Outline 09-13-14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cubs Win the World Series!

Can’t-miss listening is Pat Hughes’ ‘The Cubs Win the World Series!’ CD By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Monday, January 2, 2017 What better way for Pat Hughes to honor his own achievement by reminding listeners on his new CD he’s the first Cubs broadcaster to say the memorable words, “The Cubs win the World Series.” Hughes’ broadcast on 670-The Score was the only Chi- cago version, radio or TV, of the hyper-historic early hours of Nov. 3, 2016 in Cleveland. Radio was still in the Marconi experimental stage in 1908, the last time the Cubs won the World Series. Baseball was not broadcast on radio until 1921. The five World Series the Cubs played in the radio era – 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938 and 1945 – would not have had classic announc- ers like Bob Elson claiming a Cubs victory. Given the unbroken drumbeat of championship fail- ure, there never has been a season tribute record or CD for Cubs radio calls. The “Great Moments in Cubs Pat Hughes was a one-man gang in History” record was produced in the off-season of producing and starring in “The Cubs 1970-71 by Jack Brickhouse and sidekick Jack Rosen- Win the World Series!” CD. berg. But without a World Series title, the commemo- ration featured highlights of the near-miss 1969-70 seasons, tapped the WGN archives for older calls and backtracked to re-creations of plays as far back as the 1930s. Did I miss it, or was there no commemorative CD with John Rooney, et. -

Super Bowl Trivia 1

Across 49 Pipe type 22 Seedcase 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Opposed 52 Detractor 23 Before energy or bomb 5 It’s usually in a harbor 54 Cow remark 24 Biblical word 11 12 13 14 8 Seize 55 Shoe repair tool 25 Peculiar 11 Discover 56 Snag 26 Negative 15 16 17 13 Employ 57 After rear, dead, loose 27 Frisbee, e.g. 14 “___ you ready?” or bitter 29 Peter and Paul were two 18 19 20 21 15 Similar 58 Insect (Abbr.) 16 Identifying label 59 Jab 30 Soft-finned fish 22 23 24 18 Sick 31 Three (It.) 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 19 Conjunction Down 33 Copy 21 Weeps 1 Jai ___ 35 Round Table title 32 33 34 35 22 Divide proportionally 2 1994 Jodie Foster, Liam 38 Incapable 25 In the know Neeson flick 40 Unit of weight 36 37 38 39 28 Vow 3 Animal part 41 Engrave 29 Collector’s aim 4 Gall 42 Pinnacle 40 41 32 Thingamajig 5 Arctic treeless plain 43 Fish-eating diving bird 34 Bluepoint, e.g. 6 It’s a free country 44 Trampled 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 36 Parched 7 Precious stone 46 Division word 37 Single-pit fruit 8 Int’l. org. 47 Ghostbusters star 49 50 51 52 53 39 Cay 9 Graceful horse Moranis 40 Smaller 10 Implores 48 Flu symptom 54 55 56 42 Singing voice 12 Close at hand 50 Hack 45 Behave 17 Compass point 51 Be obliged 57 58 59 46 A Gershwin 20 Pasta unit 53 Puppy’s bark My Cousin Vinny (1992) Super Bowl Trivia 1. -

Toss-Up Questions 1. His Message in the Kind Keeper That Having Mistresses Is a "Crying Shame" Made It Very Badly Received

Toss-up Questions 1. His message in The Kind Keeper that having mistresses is a "crying shame" made it very badly received. His Spanish Fryar attacked both England's ancient enemy and Catholicism and Religio Laici was an exposition of the Protestant creed. His Heroic Stanzas commemorate the death of Oliver Cromwell, while his Astraea Redux celebrates the restoration of Charles II. FTP, name this English poet laureate who is known for Pindaric odes such as Alexander's Feast and for his long poem on the Dutch War, Annus Mirabalis. John Dryden 2. Allowed by Einstein's results, their creation requires only the use of "exotic matter" with negative energy that is thought to arise when quantum fluctuations in vacuum are suppressed. Perhaps appearing spontaneously right now on a . minute scale, Stephen Hawking says they are useless because even a single particle brings their destabilization, but we may be able to peer through them into other universes. FTP, name these theoretical shortcuts from one area of space time to another, one of which is now inhabited by Captain Sisko. Wormholes 3. His odd taste was cultivated by his father, who let him listen only to offbeat compositions that customers didn't want, and he paid tribute to Columbus with 1992's The Voyage. He studied with Milhaud (Mee-yo) and transcribed the music of Ravi Shankar, starting an Indian fascination which led to his Satyagraha. His recent operas include In the Penal Colony, based on the Kafka short story, as well as Galileo Galilei. FTP, name this composer famous for helping to popularize minimalist music with his opera Einstein on the Beach. -

DAVID WILLIAMSON Is Australia's Best Known and Most Widely

DAVID WILLIAMSON is Australia’s best known and most widely performed playwright. His first full-length play The Coming of Stork was presented at La Mama Theatre in 1970 and was followed by The Removalists and Don’s Party in 1971. His prodigious output since then includes The Department, The Club, Travelling North, The Perfectionist, Sons of Cain, Emerald City, Top Silk, Money and Friends, Brilliant Lies, Sanctuary, Dead White Males, After the Ball, Corporate Vibes, Face to Face, The Great Man, Up For Grabs, A Conversation, Charitable Intent, Soulmates, Birthrights, Amigos, Flatfoot, Operator, Influence, Lotte’s Gift, Scarlet O’Hara at the Crimson Parrot, Let the Sunshine and Rhinestone Rex and Miss Monica, Nothing Personal and Don Parties On, a sequel to Don’s Party, When Dad Married Fury, At Any Cost?, co-written with Mohamed Khadra, Dream Home, Happiness, Cruise Control and Jack of Hearts. His plays have been translated into many languages and performed internationally, including major productions in London, Los Angeles, New York and Washington. Dead White Males completed a successful UK production in 1999. Up For Grabs went on to a West End production starring Madonna in the lead role. In 2008 Scarlet O’Hara at the Crimson Parrot premiered at the Melbourne Theatre Company starring Caroline O’Connor and directed by Simon Phillips. As a screenwriter, David has brought to the screen his own plays including The Removalists, Don’s Party, The Club, Travelling North and Emerald City along with his original screenplays for feature films including Libido, Petersen, Gallipoli, Phar Lap, The Year of Living Dangerously and Balibo. -

'Pimftim. Voloes CHUCK ROAST Mg New Cuban Crisis

1BUBSDAY« FEBRUABY «, IM I TWENTY Average Daily Net Press Rm For ths W sek B n d ^ ' February 1,1964 The Royal Black Preceptory John W. Stevens Jr., son of win meet tomorrow at 8 p Jn. at Mr. and Mrs. John W. Stsvens, About Town Orange HalL M Westminster Rd., has been Prayer D ay 1 3 ,8 8 9 selected as a member of the Member of the Audit ■Vridn Ta^BOmqrrow,” m mo- championsMp imarmed drill Bureau of Oireulation tlan p M m alMUt w ig raMarcb Chapman Couit, Order of Set Feb. 14 ■ml Mtety, win tie ibown Amaranth, wiU meet and toil- team of St. Michael’s College, Mancheator^A City o f Viltago Charm Winooski Park; V t, where he is Ot tte mMting i t the Manchea* tiate candidhtes tomorrow at 7:45 p.m. at the Masonic Tom* a freshman and a member of “Let U« Pray" la the theme Quality^ with thrifty ideas... tw JajOMa to be bdd Monday the Air Force ROTC. of the World Day of Prayer •t S p jn . at the Manchester pie. Mrs. William Morrison is V O L.LX X iaiI, NO. 109 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 1964 (Claartfled AdvartWng m P egs IS) PRICE ^EViSN CEinel in charge of entertainment, service Friday, Feh. 14, al 1:80 Oountty Chib. John J. Jettersi Mias Joan C. Havens, daugh' repceaentaMve o< Bli Lilly and which will be presented after P4u. at ttia ^ r a t io n Army Oo. which Is a pharmaceutical the initiation. -

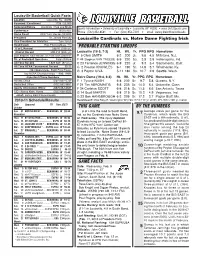

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Cubs Daily Clips

September 10, 2016 Cubs.com Lester, Bryant lower Cubs' magic number to 7 By Brian McTaggart and Jordan Ray HOUSTON -- He could have been an Astro, and on Friday night, Cubs third baseman Kris Bryant served up a reminder of the kind of impact he could have had at Minute Maid Park. Bryant, taken by the Cubs as the No. 2 overall pick in the 2013 Draft after the Astros passed on him with the top pick, clubbed a two-run homer in the fifth inning to back seven scoreless from Jon Lester to send the Cubs to a 2-0 win over the Astros, lowering Chicago's magic number to 7. "It still feels like we're just right in the middle of the season, but we feel like we're getting to baseball that actually really matters," Bryant said. "Anything can happen in the full season, so you've got to get there first, and we certainly feel like we're playing really good baseball right now." The Astros have lost three in a row and remain 2 1/2 games back in the race for the second American League Wild Card spot behind both the Orioles and Tigers, who drew even on Friday with Detroit's 4-3 win over Baltimore. "We did have some chances," Astros manager A.J. Hinch said. "Lester's a good pitcher and he has a way of finding himself out of these jams. We did get the leadoff runner on about half the innings against Lester but couldn't quite get the big hit. -

2016 National League Championship Series - Game 6 Los Angeles Dodgers Vs

2016 NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES - GAME 6 LOS ANGELES DODGERS VS. CHICAGO CUBS Saturday, October 22 - 7:08 p.m. (CDT) - Wrigley Field, Chicago, IL LHP Clayton Kershaw (2-0, 3.72) vs. RHP Kyle Hendricks (0-1, 3.00) FS1 - ESPN Radio GAME SIX: The Cubs head into Game 6 with a 3-2 series lead. Teams up 3-2 in best-of-seven LCS play are 27-10 all-time, and 16-4 when the final two games are at home. Chicago is 6-9 all-time in postseason games with a chance to clinch a series, but 0-6 in that scenario in the NLCS. The Dodgers are 16-23 all-time in postseason games in which they face elimi- nation. The Cubs won Game 5 on Thursday in Los Angeles; of the 52 previous LCS series that have gone to five games, the winner of Game 5 is 34-18. - Elias Sports Bureau LIVE ARM: Clayton Kershaw had six strikeouts in Game 2 on Sunday, giving him 102 career postseason strikeouts. He enters tonight's start ranking third among active players, behind Justin Verlander (112) and John Lackey (106). WE HAVE A HEART BEAT: After batting just 2x32 (.063) with four RBI over the first three games of the NLCS, the Cubs 3-4-5 hitters are batting .440 (11x25) with three doubles, a home run (Anthony Rizzo) and eight RBI over the last two games. UPS AND DOWNS: The Cubs have scored 26 runs in this series despite being shut out twice in five games. -

Landis, Cobb, and the Baseball Hero Ethos, 1917 – 1947

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 Lindsay John Bell Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Lindsay John, "Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18066. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18066 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconstructing baseball’s image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 by Lindsay John Bell A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural Agricultural Technology and Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Lawrence T. McDonnell, Major Professor James T. Andrews Bonar Hernández Kathleen Hilliard Amy Rutenberg The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Lindsay John Bell, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

1989-90 O-Pee-Chee Hockey Card Set Checklist

1 989-90 O-PEE-CHEE HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLI ST 1 Mario Lemieux 2 Ulf Dahlen 3 Terry Carkner RC 4 Tony McKegney 5 Denis Savard 6 Derek King RC 7 Lanny McDonald 8 John Tonelli 9 Tom Kurvers 10 Dave Archibald 11 Peter Sidorkiewicz RC 12 Esa Tikkanen 13 Dave Barr 14 Brent Sutter 15 Cam Neely 16 Calle Johansson RC 17 Patrick Roy 18 Dale DeGray RC 19 Phil Bourque RC 20 Kevin Dineen 21 Mike Bullard 22 Gary Leeman 23 Greg Stefan 24 Brian Mullen 25 Pierre Turgeon 26 Bob Rouse RC 27 Peter Zezel 28 Jeff Brown 29 Andy Brickley RC 30 Mike Gartner 31 Darren Pang 32 Pat Verbeek 33 Petri Skriko 34 Tom Laidlaw 35 Randy Wood 36 Tom Barrasso 37 John Tucker 38 Andrew McBain 39 David Shaw 40 Reggie Lemelin 41 Dino Ciccarelli 42 Jeff Sharples Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jari Kurri 44 Murray Craven 45 Cliff Ronning RC 46 Dave Babych 47 Bernie Nicholls 48 Jon Casey RC 49 Al MacInnis 50 Bob Errey RC 51 Glen Wesley 52 Dirk Graham 53 Guy Carbonneau 54 Tomas Sandstrom 55 Rod Langway 56 Patrik Sundstrom 57 Michel Goulet 58 Dave Taylor 59 Phil Housley 60 Pat LaFontaine 61 Kirk McLean RC 62 Ken Linseman 63 Randy Cunneyworth 64 Tony Hrkac 65 Mark Messier 66 Carey Wilson 67 Steve Leach RC 68 Christian Ruuttu 69 Dave Ellett 70 Ray Ferraro 71 Colin Patterson RC 72 Tim Kerr 73 Bob Joyce 74 Doug Gilmour 75 Lee Norwood 76 Dale Hunter 77 Jim Johnson 78 Mike Foligno 79 Al Iafrate 80 Rick Tocchet 81 Greg Hawgood RC 82 Steve Thomas 83 Steve Yzerman 84 Mike McPhee 85 David Volek RC 86 Brian Benning 87 Neal Broten 88 Luc Robitaille 89 Trevor Linden RC Compliments -

Study Suggests Racial Bias in Calls by NBA Referees 4 NBA, Some Players

Report: Study suggests racial bias in calls by NBA referees 4 NBA, some players dismiss study on racial bias in officiating 6 SUBCONSCIOUS RACISM DO NBA REFEREES HAVE RACIAL BIAS? 8 Study suggests referee bias ; NOTEBOOK 10 NBA, some players dismiss study that on racial bias in officiating 11 BASKETBALL ; STUDY SUGGESTS REFEREE BIAS 13 Race and NBA referees: The numbers are clearly interesting, but not clear 15 Racial bias claimed in report on NBA refs 17 Study of N.B.A. Sees Racial Bias In Calling Fouls 19 NBA, some players dismiss study that on racial bias in officiating 23 NBA calling foul over study of refs; Research finds white refs assess more penalties against blacks, and black officials hand out more to... 25 NBA, Some Players Dismiss Referee Study 27 Racial Bias? Players Don't See It 29 Doing a Number on NBA Refs 30 Sam Donnellon; Are NBA refs whistling Dixie? 32 Stephen A. Smith; Biased refs? Let's discuss something serious instead 34 4.5% 36 Study suggests bias by referees NBA 38 NBA, some players dismiss study on racial bias in officiating 40 Position on foul calls is offline 42 Race affects calls by refs 45 Players counter study, say refs are not biased 46 Albany Times Union, N.Y. Brian Ettkin column 48 The Philadelphia Inquirer Stephen A. Smith column 50 AN OH-SO-TECHNICAL FOUL 52 Study on NBA refs off the mark 53 NBA is crying foul 55 Racial bias? Not by refs, players say 57 CALL BIAS NOT HARD TO BELIEVE 58 NBA, players dismiss study on racial bias 60 NBA, players dismiss study on referee racial bias 61 Players dismiss -

Also Find Russo on Facebook.,Best Nhl Jerseys Follow @Russostrib Sutter Is a Profoundly Experienced Hockey Man at All Levels of the Game

Also find Russo on Facebook.,best nhl jerseys Follow @russostrib Sutter is a profoundly experienced hockey man at all levels of the game. Once a mortal enemy of the Oilers as a nasty,michigan hockey jersey, grinding forward with the New York Islanders,custom sports jerseys,?the four-time Stanley Cup champion has carved out a post-playing career in coaching and scouting. Most recently he has served the arch rival Calgary Flames as Director of Player Personnel,nfl caps,football jersey sizes, where he teamed up with brothers Darryl and Brent in key organizational roles. For all of the various Sutter brothers,basketball jersey, sons,design your own baseball jersey, cousins,discount nfl jerseys, nephews,wholesale baseball jersey, ?etc. that have been all over the league pretty much forever,nike nfl pro combat, this is the first time that one has been involved with the Oilers at any level. I’m not sure what to think about that – I’ve become pretty accustomed to rooting against those guys over the years. P.S. Here is a link to my colleague David Staples’ critique of the Oilers pro scouting department. Take Our Poll Email Michael to talk about hockey. Posted by: Bruce McCurdy This is Michael Russo's 17th year covering the National Hockey League. He's covered the Minnesota Wild for the Star Tribune since 2005 following 10 years of covering the Florida Panthers for the Sun-Sentinel. Michael uses ?¡ãRusso?¡¥s Rants?¡À to feed a wide-ranging hockey-centric discussion with readers,create your own nfl jersey, and can be heard weekly on KFAN (100.3 FM) radio.