Centralization, Professionalism, and Police Malfeasance in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Army Noncommissioned Officer Guide

HEADQUARTERS FM 7-22.7 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY (TC 22-6) THE ARMY NONCOMMISSIONED OFFICER GUIDE Sergeant of Riflemen 1821 Sergeant Major of the Army 1994 DECEMBER 2002 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release, distribution is unlimited * FM 7-22.7 (TC 22-6) Field Manual Headquarters No. 7-22.7 Department of the Army 23 December 2002 The Army Noncommissioned Officer Guide Contents Page FIGURES ......................................................................................iii VIGNETTES ..................................................................................iv PREFACE......................................................................................v CHARGE TO THE NONCOMMISSIONED OFFICER......................vii THE NCO VISION........................................................................ viii INTRODUCTION........................................................................... ix INTRODUCTORY HISTORICAL VIGNETTES ................................xii CHAPTER 1 -- HISTORY AND BACKGROUND........................... 1-1 History of the Army Noncommissioned Officer............................... 1-3 Army Values ............................................................................. 1-22 NCO Professional Development ................................................. 1-25 The NCO Transition .................................................................. 1-32 CHAPTER 2 -- DUTIES, RESPONSIBILITIES AND AUTHORITY OF THE NCO......................................................... 2-1 Assuming a Leadership -

School Breaks Ground on Multi-Purpose Athletic Field with Lights Achievement • Spring 2018 1 Achievement Spring 2018

Spring 2018 Achievement Asheville School Alumni Magazine School Breaks Ground On Multi-Purpose Athletic Field With Lights Achievement • Spring 2018 1 Achievement Spring 2018 BOARD OF TRUSTEES An Education For An Inspired Life Published for Alumni & Mr. Walter G. Cox Jr. 1972, Chairman P ‘06 Friends of Asheville School Ms. Ann Craver, Co-Vice Chair P ‘11 by the Advancement Department Asheville School Mr. Robert T. Gamble 1971, Co-Vice Chair 360 Asheville School Road Asheville, North Carolina 28806 Mr. Marshall T. Bassett 1972, Treasurer 828.254.6345 Dr. Audrey Alleyne P ’18, ’19 www.ashevilleschool.org (Ex officio Parents’ Association) Editor Mr. Haywood Cochrane Jr. P ’17 Bob Williams Mr. Thomas E. Cone 1972 Assistant Head of School for Advancement Dan Seiden Mr. Matthew S. Crawford 1984 Writers Mr. D. Tadley DeBerry 1981 Alex Hill Tom Marberger 1969 Mr. James A. Fisher 1964 Travis Price Bob Williams Dr. José A. González 1985 P ’20 Proof Readers Ms. Mary Robinson Hervig 2002 Tish Anderson Bob Williams Ms. Jean Graham Keller 1995 Travis Price Mr. Richard J. Kelly 1968 P ’20 Printing Mr. Nishant N. Mehta 1998 Lane Press Mr. Archibald R. Montgomery IV Photographers Blake Madden (Ex officio Head of School) Sheila Coppersmith Eric Frazier Dr. Gregory K. Morris 1972 Bob Williams Mr. J. Allen Nivens Jr. 1993 A special thanks to the 1923 Memorial Archives for providing many of the archival photographs (Ex officio Alumni Association) in this edition. Ms. Lara Nolletti P ’19 Mr. Laurance D. Pless 1971 P ’09, P ’13 Asheville School Mission: To prepare our students for college and for life Mr. -

Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brad T. Eidahl December 2017 © 2017 Brad T. Eidahl. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile by BRAD T. EIDAHL has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. Barr-Melej Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EIDAHL, BRAD T., Ph.D., December 2017, History Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. Barr-Melej This dissertation examines the struggle between Chile’s opposition press and the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). It argues that due to Chile’s tradition of a pluralistic press and other factors, and in bids to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy, Pinochet and his top officials periodically demonstrated considerable flexibility in terms of the opposition media’s ability to publish and distribute its products. However, the regime, when sensing that its grip on power was slipping, reverted to repressive measures in its dealings with opposition-media outlets. Meanwhile, opposition journalists challenged the very legitimacy Pinochet sought and further widened the scope of acceptable opposition under difficult circumstances. Ultimately, such resistance contributed to Pinochet’s defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, initiating the return of democracy. -

Costa Rica, Haiti and Panama 99 the Cases of Costa Rica, Haiti and Panama

Cha p ter 9: The cases of Costa Rica, Haiti and Panama 99 The cases of Costa Rica, Haiti and Panama MATION FOR IN Costa Rica C SI A B Population 4,870,000 Comparative increase (percentage variation 2008-2015) Territorial Extension 51,000 km2 Security State GDP Budget Budget GDP (US$) 56,908,000,000 Public Force Personnel 14,497* Security Budget (US$) 949,094,945 159% 126% 91% *Dependents of the Ministry of Security Principal Actors Security Budget as a Percentage of GDP, 2004-2015 1,000,000,000 Institutions Dependents 900,000,000 800,000,000 - Public Force (Civil Guard, Rural Guard, Coast 700,000,000 Guard, Aerial Surveilance, Drugs Control). 600,000,000 Ministry of Public -Police School. 500,000,000 Security - Directorate of Private Security Services. 400,000,000 300,000,000 - General Directorate of Armaments. 200,000,000 100,000,000 0 Ministry of - Directorate of Migration and Foreign Persons. 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Interior and Police - Communal Development. Security Budget (current US$), 2004-2015 4.0% 3.5% - General Directorate of Social Adaption. Ministry of - General Directorate for the Promotion of 3.0% Justice and Peace and Citizen Coexistence. 2.5% Peace - National Youth Network for the prevention of violence. 2.0% - Violence Observatory. 1.5% - National Directorate of Alternative Confl ict Resolution. 1.0% - Commission for Regulating and Rating Public 0.5% Events. - Technical Secretariat of the National 0.0% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Commission for the Prevention of Violence and Promotion of Social Peace. -

Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century

The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century By Megan Marie Adams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair Professor Richard Candida-Smith Professor Kim Voss Fall 2012 1 Abstract The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century by Megan Marie Adams Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair My dissertation uncovers a history of labor insurgency and civil rights activism organized by the lowest-ranking members of the Chicago police. From 1950 to 1984, dissenting police throughout the city reinvented themselves as protesters, workers, and politicians. Part of an emerging police labor movement, Chicago’s police embodied a larger story where, in an era of “law and order” politics, cities and police departments lost control of their police officers. My research shows how the collective action and political agendas of the Chicago police undermined the city’s Democratic machine and unionized an unlikely group of workers during labor’s steep decline. On the other hand, they both perpetuated and protested against racial inequalities in the city. To reconstruct the political realities and working lives of the Chicago police, the dissertation draws extensively from new and unprocessed archival sources, including aldermanic papers, records of the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, and previously unused collections documenting police rituals and subcultures. -

12233—Víctor Améstica Moreno and Others in Chile

OEA/Ser.L/V/II.150 REPORT No. 137 /19 Doc. 147 6 September 2019 CASE 12.233 Original: Spansih FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT VICTOR AMESTICA MORENO AND OTHERS CHILE Approved electronically by the Commission on September 6, 2019 Cite as: IACHR, Report No. 137/2019 , Case 12.233. Friendly Settlement. Victor Amestica Moreno and others. Chile. September 6, 2019. www.cidh.org REPORT No.137/19 CASE 12.233 FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT VÍCTOR AMÉSTICA MORENO ET AL. CHILE SEPTEMBER 6, 20191 I. SUMMARY AND PROCEDURAL ASPECTS RELATED TO THE FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT PROCESS 1. On November 1, 1999, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Commission” or the “IACHR”) received a petition from the Corporación de Promoción de la Defensa de los Derechos del Pueblo [Corporation for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights], or CODEPU (hereinafter “the petitioners”), against the Republic of Chile (hereinafter “the State” or “the Chilean State”), alleging that Víctor Améstica Moreno, Alberto Araneda Muñoz, Héctor Martínez Vasquez, Oscar Sepulveda Alarcon, and Alejandro César Sánchez Canales—all members of Carabineros de Chile2 (hereinafter “the Carabineros”)—had been victims of an arbitrary evaluation process carried out by officials of the Carabineros, in which their basic rights were violated, and that they had then been expelled from the institution with no substantive judicial decision having been issued regarding the violation of their rights. They further alleged that their respective spouses, Jenny Burgos Orrego, Marisol Valencia Poblete, Johanna Valdebenito Pinto, Carmen Araya Cordero, and María Angélica Olguín (hereinafter “the spouses of the Carabineros”), were discriminated against for being their wives. -

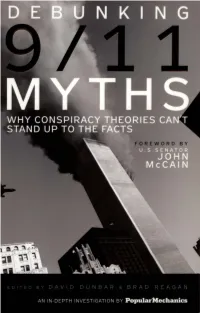

Debunking 911 Myths.Pdf

PRAISE FOR DEBUNKING 9111 MYTHS "Debunking 9111 Myths is a reliable and rational answer to the many fanciful conspiracy theories about 9/11. Despite the fact that the myths are fictitious, many have caught on with those who do not trust their government to tell the truth anymore. Fortunately, the govern ment is not sufficiently competent to pull off such conspiracies and too leaky to keep them secret. What happened on 9/11 has been well established by the 9/11 Commission. What did not happen has now been clearly explained by Popular Mechanics." -R 1 cHARD A. cLARKE, former national security advisor, author of Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror "This book is a victory for common sense; 9/11 conspiracy theorists beware: Popular Mechanics has popped your paranoid bubble world, using pointed facts and razor-sharp analysis." -Au s T 1 N BAY, national security columnist (Creators Syndicate), author (with James F. Dunnigan) of From Shield to Storm: High-Tech Weapons, Military Strategyand Coalition Warfare in the Persian Gulf "Even though I study weird beliefs for a living, I never imagined that the 9/11 conspiracy theories that cropped up shortly after that tragic event would ever get cultural traction in America, but here we are with a plethora of conspiracies and no end in sight. What we need is a solid work of straightforward debunking, and now we have it in Debunking 9111 Myths. The Popular Mechanics article upon which the book is based was one of the finest works of investigative journalism and skep tical analysis that I have ever encountered, and the book-length treat ment of this codswallop will stop the conspiracy theorists in their fantasy-prone tracks. -

Country Assessment on VAW CHILE

Country Assessment on VAW CHILE Consultant: Soledad Larrain, in collaboration with Lorena Valdebenito and Luz Rioseco Santiago, Chile July 2009 0 RESPONSIBILITIES The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and not attributable in any way to the United Nations, its associated organizations, its member states, or the members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries that they represent. The United Nations does not guarantee the exactitude of the information included in this publication and assumes no responsibility for the consequences of its use. 1 Table of Contents Responsibilities 1 Abbreviations 3 I. Executive Summary 4 1.1 Conceptual considerations 4 1.2 Main findings and challenges 5 1.3 Significant advances in GBV response 5 1.4 Pending challenges 9 1.5 Final comments 15 II. Country Profile 16 III. Scale of the Problem 17 IV. Public Policies 23 4.1 The route from the initial formal complaint to an integral victim response 23 4.2 Legal frameworks 27 4.3 The response of government agencies to gender-based violence 35 4.4 Campaigns from non-governmental organizations 56 4.5 Registration of information 57 V. Non-Governmental Organisations 59 VI. Conclusions and Challenges 63 VII. Final Comments 73 VIII. Bibliography 74 2 Abbreviations Centre for Victims of Sexual Assaults CAVAS Response. Centres for Violent Crime Victim CAVIS Response. Gender-based Violence GBV Inter American Human Rights CIDH Commission Inter American Women’s Commission CIM Intra-family -

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People”

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015 “Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People” A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015, organized jointly by the Japan Studies Association of Canada (JSAC), the Japanese Association for Canadian Studies (JACS) and the Japan-Canada Interdisciplinary Research Network on Gender, Diversity and Tohoku Reconstruction (JCIRN). Edited by David W. Edgington (University of British Columbia), Norio Ota (York University), Nobuyuki Sato (Chuo University), and Jackie F. Steele (University of Tokyo) © 2016 Japan Studies Association of Canada 1 Table of Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Contributors ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 7 SECTION A: ECONOMICS AND POLITICS IN JAPAN .......................................................................... -

Police Ranks

Policing and Crime Bill Factsheet: Police Ranks Current rank structure 1. Presently, the police rank structure is set out in the Police Act 1996 (“the 1996 Act”), the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 (“the 2011 Act”) and regulations made under the 1996 Act. The 1996 Act allows the Secretary of State to make regulations on the police rank structure, subject to their being prepared or approved by the College of Policing. However, various provisions in both Acts require those regulations to include a number of police ranks. The statutory ranks below the chief officer ranks in all forces in England and Wales are set out in sections 9H and 13 of the 1996 Act. They include: Constable Sergeant Inspector Chief inspector Superintendent Chief superintendent 2. Additionally, the 2011 Act requires every force to have at least one officer at each of the chief officer ranks. The chief officer ranks in all English and Welsh forces, other than the Metropolitan Police and City of London Police, are: Assistant chief constable Deputy chief constable Chief constable 3. Chief officer ranks in the Metropolitan Police are: Commander Deputy assistant commissioner Assistant commissioner Deputy commissioner Commissioner 4. Chief officer ranks in the City of London Police are: Commander Assistant commissioner Commissioner In these provisions the Home Secretary has very little flexibility in the rank structure that she may provide for in regulations and, accordingly, regulation 4 of the Police Regulations 2003 simply specifies those ranks already stipulated in primary legislation. 1 The Leadership Review 5. In an oral statement on 22 July 2014 (House of Commons, Official Report, columns 1265 to 1277), the Home Secretary announced that she had asked the College of Policing to conduct a fundamental review of police leadership. -

BVCM019068 Rabih Mroué. Image(S), Mon Amour. Fabrications

Rabih Mroué Aurora Fernández Polanco Image(s), mon amour Bilal Khbeiz Pablo Martínez FABRICATIONS Rabih Mroué Rabih Mroué FABRICATIONS Lina Saneh Image(s), mon amour E!"#O$%&o'%(ión)*+n S,-. Rabih Mroué Image(s), mon amour FABRICATIONS ÍNDICE RABIH MROUÉ INDEX 100 Once años, tres meses y cinco días CA2M 104 Eleven Years, Three Months and 4 Five Days Presentación 5 108 Presentation Una frase poética 112 7 A Line of Poetry Casa antigua Old house 116 Biokhraphia AURORA F. POLANCO 138 Biokhraphia 10 Fabrications 158 Image(s), mon amour Abuelo, padre e hijo 36 176 Fabrications Grandfather, Father and Son Image(s), mon amour 188 BILAL KHBEIZ ¿Quién teme a la representación? 62 216 Empezar todo de nuevo Who´s Afraid of 68 Representaion? Starting All Over Again PABLO MARTÍNEZ 74 Cuando las imágenes disparan 86 When Images Shoot 242 358 Teatro en oblicuo La revolución pixelada 250 378 Theatre in Oblique The Pixelated Revolution 258 394 Lo que ha pasado está tan lejos y Guerra 2006 lo que está por venir tan cerca 398 272 War 2006 What has Slipped Away is So Far and What is Yet to Come 402 So Close Estar en el espacio público sin cabeza 284 410 Three posters Being in the Public Space 302 Without a Head Three Posters 416 316 El actor Los habitantes de imágenes 420 338 The Actor The Inhabitants of Images 425 Biografía Biography 426 Listado de obra en exposición Works in exhibition 4 Image(s) mon amour Presentación PRESENTACIÓN las narrativas más subjetivas y persona- les hasta las colectivas. -

Shift Work and Occupational Stress in Police Officers

SHAW68_proof ■ 11 November 2014 ■ 1/5 Safety and Health at Work xxx (2014) 1e5 55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect 56 57 Safety and Health at Work 58 59 60 journal homepage: www.e-shaw.org 61 62 63 Original Article 64 65 1 Shift Work and Occupational Stress in Police Officers 66 2 67 3 1,* 1 1 1 1 68 Q10 Claudia C. Ma , Michael E. Andrew , Desta Fekedulegn ,JaK.Gu , Tara A. Hartley , 4 Luenda E. Charles 1,2, John M. Violanti 2, Cecil M. Burchfiel 1 69 5 Q1Q2 70 6 1 Biostatistics and Epidemiology Branch, Health Effects Laboratory Division, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV, USA 71 2 7 Department of Epidemiology and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, 72 8 New York, NY, USA 73 9 74 10 75 article info abstract 11 76 12 77 Article history: Background: Shift work has been associated with occupational stress in health providers and in those 13 78 Received 26 March 2014 working in some industrial companies. The association is not well established in the law enforcement 14 79 Received in revised form workforce. Our objective was to examine the association between shift work and police work-related 15 3 October 2014 stress. 80 16 Accepted 6 October 2014 Methods: The number of stressful events that occurred in the previous month and year was obtained 81 17 using the Spielberger Police Stress Survey among 365 police officers aged 27e66 years. Work hours were 82 Keywords: 18 derived from daily payroll records.