Linking Conservation with Cplrs: Lessons from Management of Gir- Protected Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gunotsav-5/2014

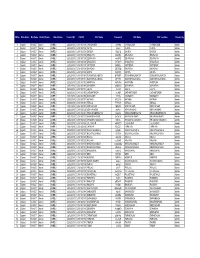

GUNOTSAV-5/2014 NAME : Dr. S.K. Nanda Office Type : IAS (State Level) Desig, Dept & HOD : Additional Chief Secretary to Govt.,Home Department, Sachivalaya, Gandhinagar. Alloted District : THE DANG Alloted Taluka : AHWA Group Name : BRC-242301-Group22 Liason Officer : Sejalben M Desai, CRC coordinator - 9429142551. No of Visits Upper by external Gunotsav-4 Sr. Primary Stds officer Self Date School & Village Name No. available during Assessment (Yes/No) Gunotsav Grade 1,2,3,4 1 20-11-2014 CHIKTIYA PRIMARY SCHOOL, CHIKATIYA Yes 2 B 2 20-11-2014 ISDAR PRIMARY SCHOOL, ISDAR(GADHVI) No 0 A 3 20-11-2014 SARVAR PRIMARY SCHOOL, SARWAR Yes 1 B 4 20-11-2014 GAURIYA PRIMARY SCHOOL, GAURYA(GAVARIA) No 0 B 5 21-11-2014 KUMBHIPADA PRIMARY SCHOOL, ISDAR(GADHVI) No 0 B 6 21-11-2014 ASHRAM SHALA CHIKHATIYA, CHIKATIYA Yes 1 C 7 21-11-2014 SODMAL PRIMARY SCHOOL, SODMAL No 1 B 8 21-11-2014 TOKARDAHAD PRIMARY SCHOOL, GAURYA(GAVARIA) No 0 A 9 22-11-2014 NADAGKHADI PRIMARY SCHOOL, NADAGKHADI Yes 2 C 10 22-11-2014 DHADHARA PRIMARY SCHOOL, DHADHRA No 1 B 11 22-11-2014 HANVATCHOND PRIMARY SCHOOL, HANWATCHOND Yes 2 A GUNOTSAV-5/2014 NAME : Shri G.R. Aloria Office Type : IAS (State Level) Desig, Dept & HOD : Additional Chief Secretary to Government, Urban Development & Urban Housing Department, Alloted District : SURAT Alloted Taluka : OLPAD Group Name : BRC-242208-Group1 Liason Officer : BIPINBHAI PAREKH, CRC MULAD - 7383794647. No of Visits Upper by external Gunotsav-4 Sr. Primary Stds officer Self Date School & Village Name No. -

Protected Areas in News

Protected Areas in News National Parks in News ................................................................Shoolpaneswar................................ (Dhum- khal)................................ Wildlife Sanctuary .................................... 3 ................................................................... 11 About ................................................................................................Point ................................Calimere Wildlife Sanctuary................................ ...................................... 3 ......................................................................................... 11 Kudremukh National Park ................................................................Tiger Reserves................................ in News................................ ....................................................................... 3 ................................................................... 13 Nagarhole National Park ................................................................About................................ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 .................................................................... 14 Rajaji National Park ................................................................................................Pakke tiger reserve................................................................................. 3 ............................................................................... -

Why the Lion Reintroduction Project ? Manoj Mishra*

Why the Lion Reintroduction Project ? Manoj Mishra* Isolated populations of endangered species are at severely depleted as a result of an outbreak of much greater risk compared to populations that are canine distemper virus in the early 1990s. It is well-distributed. The risk is even more acute if the believed that 75% of the lions had been infected species in question survives as a single, small and at least 30% of the population was wiped out population confined to a single locality. Currently by the infection. If an epidemic of such proportions Asiatic lions (Panthera leo persica) are up against were to affect the lions of Gir, it would be very precisely such odds. Once widely occurring in India difficult to save them from extinction, given the in the northern semi-arid scrub-grassland habitats much smaller size of Gir and also the relatively from west to east and other arid scrub areas in the smaller lion population. Genetically speaking, earlier peninsula, the Asiatic lion rapidly started losing the rapid decline in Asiatic lions occurred in the late ground to diversion and degradation of its natural 19th and early 20th century in a short time-span habitat by extension of human settlements, as well and even the small remaining population must have as overuse and abuse. The constraining impact of carried substantial proportions of the original shrinkage, fragmentation and degradation of lion genetic attributes. This allowed it to recover, given habitats was compounded by the pressures of good conservation support. If such a crash occurs uncontrolled hunting, predominantly by British now, the genetic viability of the population will take sports hunters as well as Indian maharajas, which a serious hit, imperiling its long-term survival. -

February 2008

ExamSeatNo Trial Employee Name Designation Secretariate Department Institute Practical Theory Total Result Exam Date PATEL DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117008 1 BIPINCHANDRA JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 25 8 33 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT ISHWERBHAI TREASURY OFFICE PATEL DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117009 1 MAHENDRABHAI JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 5 5 10 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT CHHAGANBHAI TREASURY OFFICE BRAHMBHATT DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117010 1 KETANKUMAR JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 44 26 70 PASS 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT HARIKRISHAN TREASURY OFFICE PANDYA DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117011 1 PARESHKUMAR JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 27 4 31 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT PREMJI TREASURY OFFICE PRAJAPATI DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT DEPUTY FINANCE 69890117012 1 SAVAJIBHAI ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 29 25 54 PASS 30/01/2008 ACCOUNTANT DEPARTMENT CHATARABHAI TREASURY OFFICE PANDYA DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117013 1 BIPINCHANDRA JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 31 26 57 PASS 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT MANSUKHLAL TREASURY OFFICE MALEK DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117014 1 NAGARKHAN JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 26 4 30 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT KALAJIBHAI TREASURY OFFICE PATEL DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117015 1 AMBARAM JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 19 7 26 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT MANAGIBHAI TREASURY OFFICE HOME PATEL RADIO DEPARTMENT/POLI COMMANDANT 10190146001 1 BABULAL HOME DEPARTMENT 40 25 65 PASS 06/02/2008 TECHNICIAN CE WIRELESS S R P F GR-2 POPATLAL BRANCH ASARI HEAD POLICE KHADIA POLICE 10190146002 1 RAJESHKUMAR HOME DEPARTMENT 0 0 0 ABSENT 06/02/2008 QUANSTABLE DEPARTMENT STATION JIVJIBHAI BHATI SHAHIBUAG POLICE 10190146003 1 BHARATSINH UPC HOME DEPARTMENT POLICE 0 0 0 ABSENT 06/02/2008 DEPARTMENT MANUJI STATION CHITRODA SHAHIBUAG BHUPENDRASIN POLICE 10190146004 1 UPC HOME DEPARTMENT POLICE 0 0 0 ABSENT 06/02/2008 H DEPARTMENT STATION PRATPSINH ESHARANI POLICE THE 10190146005 1 JAYDEV DRIVER P.C. -

Wildlife Sanctuaries of India

Wildlife sanctuaries of India Srisailam Sanctuary, Andhra Pradesh The largest of India's Tiger Reserves, the Nagarjunasagar Srisailam Sanctuary ( 3568 sq. km.); spreads over five districts - Nalgonda, Mahaboobnagar, Kurnool, Prakasam and Guntur in the state of Andhra Pradesh. The Nagarjunasagar-Srisailam Sanctuary was notified in 1978 and declared a Tiger Reserve in 1983. The Reserve was renamed as Rajiv Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary in 1992. The river Krishna flows through the sanctuary over a distance of 130 km. The multipurpose reservoirs, Srisailam and Nagarjunasagar, which are important sources of irrigation and power in the state are located in the sanctuary. The reservoirs and temples of Srisailam are a major tourist and pilgrim attraction for people from all over the country and abroad. The terrain is rugged and winding gorges slice through the Mallamalai hills. Adjoining the reserve is the large reservoir of the Nagarjunasagar Dam on the River Krishna. The dry deciduous forests with scrub and bamboo thickets provide shelter to a range of animals from the tiger and leopard at the top of the food chain, to deer, sloth bear, hyena, jungle cat, palm civet, bonnet macaque and pangolin. In this unspoilt jungle, the tiger is truly nocturnal and is rarely seen. Manjira Wildlife Sanctuary Total Area: 3568-sq-kms Species found: Catla, Rahu, Murrel, Ech Paten, Karugu, Chidwa,Painted Storks, Herons, Coots, Teals, Cormorants, Pochards, Black and White Ibises, Spoon Bills, Open Billed Storks etc About Manjira Wildlife Sanctuary: Manjira bird sanctuary spreads over an area of 20 sq.kms and is the abode of a number of resident and migratory birds and the marsh crocodiles. -

Rajkot -Passwords

SR No State Name Div Name District Name Block Name Created On CSC ID CSC Name Password VLE Name CSC Location Created By 1 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300101 CHANDGADH 0VPNts CHANDGADH CHANDGADH Admin 2 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300102 CHITAL rvrmrn CHITAL CHITAL Admin 3 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300103 DAHIDA HXg2Hq DAHIDA DAHIDA Admin 4 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300104 DEVALIYA DwLqBn DEVALIYA DEVALIYA Admin 5 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300105 DEVRAJIYA enoQFE DEVRAJIYA DEVRAJIYA Admin 6 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300106 DHOLARVA 5VFdmH DHOLARVA DHOLARVA Admin 7 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300107 FATTEPUR AMRELI FATTEPUR FATTEPUR Admin 8 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300108 GAVADKA SBGPgd GAVADKA GAVADKA Admin 9 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300109 GIRIYA fkAETW GIRIYA GIRIYA Admin 10 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300110 GOKHARVALA MOTA dYFVWT GOKHARVALA MOTA GOKHARVALA MOTA Admin 11 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300111 GOKHARVALA NANA gFTY02 GOKHARVALA NANA GOKHARVALA NANA Admin 12 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300112 HARIPURA AbPuGw HARIPURA HARIPURA Admin 13 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300113 ISHVARIYA 6MUeX5 ISHVARIYA ISHVARIYA Admin 14 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300114 JALIYA 1CzoYI JALIYA JALIYA Admin 15 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300115 JASVANTGADH noJABY JASVANTGADH JASVANTGADH -

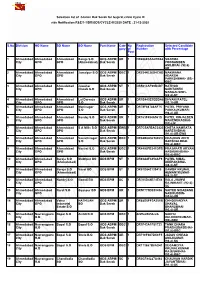

Selection List of Gramin Dak Sevak for Gujarat Circle Cycle III Vide Notification R&E/1-1/DR/GDS/CYCLE-III/2020 DATE : 21-12-2020

Selection list of Gramin Dak Sevak for Gujarat circle Cycle III vide Notification R&E/1-1/DR/GDS/CYCLE-III/2020 DATE : 21-12-2020 S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Bareja S.O GDS ABPM/ UR 1 DR456E3AA2FB84 SHARMA City GPO GPO (Ahmedabad) Dak Sevak POONAMBEN ANILBHAI- (92.8)- UR 2 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Jamalpur S.O GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR5344E26D4CAD MAKWANA City GPO GPO Dak Sevak ADARSH PARESHBHAI- (92)- OBC 3 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Jawahar GDS ABPM/ ST 1 DR5614AF99B4D7 RATHOD City GPO GPO Chowk S.O Dak Sevak SARITABEN MANGALSINH- (88.4)-ST 4 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Lal Darwaja GDS ABPM/ UR 1 DR1B443E3EBDA8 DHVANI PATEL- City GPO GPO S.O Dak Sevak (93.1)-UR 5 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Maninagar GDS ABPM/ UR 1 DR79F68784AF75 PATEL PRIYANK City GPO GPO S.O Dak Sevak PANKAJKUMAR- (94.2)-UR 6 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Nandej S.O GDS ABPM/ UR 1 DR163F454A561D PATEL KINJALBEN City GPO GPO Dak Sevak MAHENDRABHAI- (93)-UR 7 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad S A Mills S.O GDS ABPM/ EWS 1 DR7C5AFEAC3423 CHETA NAMRATA City GPO GPO Dak Sevak HARESHBHAI- (91.8)-UR-EWS 8 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Vasisthnagar GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR04B6A5218EC3 CHAUHAN ADITI City GPO GPO S.O Dak Sevak HARSHALBHAI- (92.4)-OBC 9 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Vastral S.O GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR4495FB341DFB PRAJAPATI ARYAN City GPO GPO Dak Sevak HASMUKHBHAI- (95.4)-OBC 10 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Bareja S.O Muktipur BO GDS BPM ST 1 DR63A8F4454AF9 -

INDIA Pilgrimage in Wildlife Sanctuaries Outline of Presentation

INDIA Pilgrimage in Wildlife Sanctuaries Outline of Presentation • Context • Where we work • Our approach to pilgrimage in PAs • Lessons learned • Way forward Protected Areas of India Type of Protected Number Area (sq. Kms) % of Geographical Area Area of India National Parks (NPs) 103 40500.13 1.23 Wildlife Sanctuaries 531 117607.72 3.58 (WLSs) Conservation 65 2344.53 0.07 Reserves (CRs) Community Reserves 4 20.69 0.00 Total Protected Areas 703 160473.07 4.88 (PAs) Percentage Area under Forest Cover 21.23% of Geographical Area of India Source: http://www.wiienvis.nic.in/Database/Protected_Area_854.aspx ENVIS centre on Wildlife & Protected Areas WILDLIFE SANCTUARIES OF INDIA TIGER RESERVES OF INDIA ARC/GPN in Protected Areas Wildlife Sanctuary/National Park/Tiger Partner Reserve Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, TN ATREE Ranthambore National Park, RJ ATREE Srivilliputhur Grizzled Squirrel Sanctuary, TN WTI Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, TN WTI Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary, K’tka ATREE Gir National Park, Gujarat BHUMI Arunachala Hills, TN FOREST WAY Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve (KMTR) • KMTR is in the Western Ghats in the state of Tamil Nadu. • It was created in 1988 by combining Kalakad Wildlife Sanctuary and Mundanthurai Wildlife Sanctuary. • The Tiger Reserve has an area of 818 sq. Kms of which a core area of 400 sq. Km has been proposed as a national park. • The reserve is the catchment area for 14 rivers and streams and shelters about 700 endemic species of Flora and Fauna. KMTR Sorimuthu Ayyanar Temple • Sorimuthu Ayyanar Temple is worshipped by local tribes and people living in villages surrounding the reserve. -

UNIT 11 WILDLIFE SANCTUARIES and NATIONAL PARK Structure 11.0 Objectives 11.1 Introduction 11.2 Wildlife Reserves, Wildlife Sanc

UNIT 11 WILDLIFE SANCTUARIES AND NATIONAL PARK Structure 11.0 Objectives 11.1 Introduction 11.2 Wildlife Reserves, Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks: Concept and Meaning 11.3 Tiger Reserves 11.4 Project Elephant 11.5 Indian Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks and their specialties 11.6 Wildlife National Parks Circuits of India 11.7 Jeep Safari and Wildlife Tourism 11.8 Let us sum up 11.9 Keywords 11.10 Some Useful books 11.11 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 11.12 Reference and bibliography 11.13 Terminal Questions 11.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit, learners should be able to: understand about Wildlife Reserves, National Parks and Sanctuaries differentiate between National Parks and Sanctuaries learn about various famous National Parks and Sanctuaries and their main attractions understand about Wildlife Protection Act of India explore Tiger Reserves and Elephant Reserves explain Wildlife Tourism 11.1 INTRODUCTION Wildlife of India is important natural heritage and tourism attraction. National Parks, Biosphere Reserves and Wildlife Sanctuaries which are important parts of tourism attraction protect the unique wildlife by acting as reserve areas for threatened species. Wildlife tourism means human activity undertaken to view wild animals in a natural setting. All the above areas are exclusively used for the benefit of the wildlife and maintaining biodiversity. “Wildlife watching” is simply an activity that involves watching wildlife. It is normally used to refer to watching animals, and this distinguishes wildlife watching from other forms of wildlife-based activities, such as hunting. Watching wildlife is essentially an observational activity, although it can sometimes involve interactions with the animals being watched, such as touching or feeding them. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : GUJARAT DISTRICT : Ahmadabad Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 VIJAYFARM CHELDA , PIN CODE: 382145, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: 0395646, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NA 10 - 50 NIC 2004 : 1020-Mining and agglomeration of lignite 2 SOMDAS HARGIVANDAS PRAJAPATI KOLAT VILLAGE DIST.AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1990 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. 3 NABIBHAI PIRBHAI MOMIN KOLAT VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1992 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. 4 NANDUBHAI PATEL HEBATPUR TA DASKROI DIST AHMEDABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 5 BODABHAI NO INTONO BHATHTHO HEBATPUR TA DASKROI DIST AHMEDABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 6 NARESHBHAI PRAJAPATI KATHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: 382430, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 7 SANDIPBHAI PRAJAPATI KTHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: 382430, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX 2005 10 - 50 NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 8 JAYSHBHAI PRAJAPATI KATHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX 2005 10 - 50 NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

Report of the Census of 1911 A. D. of the Junagadh State

REPORT THE CENSUS OF t911 A'~ D. THE JUNIQADH STATE BY M. A. TURKHUD Esquire, F. O. S., •• 06C E:I 1913. PtUN,i;I<:1l AI', TIU~ J I'NAGADH STATI': PRESS. 1fo. 31 of 1911. L. ROBERTSON, EsQUIRE, I. C. S., Administrator, J unagadh. From M. A. TURKHUD, EsQUmE, .F. G. 5., Census General Superintendent, Junagadh. JUlIagadh, 29th Feb'l'tlary 1912. Sir, I have the honour to forward herewith my report of the Census of Junagadh State for 1911 with fh"e Appendices and six Charts. A domestic calamity, anxiety during the period of; the serioul ilkress of tILe Minor Nawab Saheb and pressure of other work ha.ve given rise to many interruptions in the continuity of working and writing. To my Assistant, Mr. Anantrai Nanalal Buch, my best thanks are due~ He has worked with· earnest' zeal and has deservedly earned the First Class Certificate froin your hands at the Coronation Durbar. I trust that his labours in this work of Imperial importance will receive some furthe~ t8.ugible reward. Other recipients of these certificates were in the 2nd class and Brd class. and t~r names are:- 2nd mass. Mr. JeysukhIaJ Rudm.ji l Volunteers. " Bhagv8nlal Fulshanker .s " Krishnalill Chhaganlal Port Officer. " A. Latifkhan, Overseer, Po W~ D. and " Vyankatrai Ambaidas- } " Tmmhttkrai J eyshanker Oil my office estRbliahment. Of these I must draw your special attention to. Mr. Vyankatrai, who has been retained to the mst and will remain on the .tal till the Census office finally closes on 31st H!Lrch next. Srd ClaS8. -