Handbook on Strategies to Reduce Overcrowding in Prisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration

Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science Volume 4 Article 3 5-10-2016 Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration Peter Hanna San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Hanna, Peter (2016) "Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration," Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: Vol. 4 , Article 3. https://doi.org/10.31979/THEMIS.2016.0403 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol4/iss1/3 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Justice Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science by an authorized editor of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration Abstract This paper examines the costs and impacts of prison overpopulation and mass incarceration on individuals, families, communities, and society as a whole. We start with an overview of the American prison system and the costs of maintaining it today, and move on to an account of the historical background of the prison system to provide context for the discussions later in this paper. This paper proceeds to go into more detail about the financial and social costs of mass incarceration, concluding that the costs of the prison system outweigh its benefits. This paper will then discuss the stigma and stereotypes associated with prison inmates that are formed and spread through mass media. -

Announcement the International Historical, Educational, Charitable and Human Rights Society Memorial, Based in Moscow, Asks

Network of Concerned Historians NCH Campaigns Year Year Circular Country Name original follow- up 2017 88 Russia Yuri Dmitriev 2020 Announcement The international historical, educational, charitable and human rights society Memorial, based in Moscow, asks you to sign a petition in support of imprisoned historian and Gulag researcher Yuri Dmitriev in Karelia. The petition calls for Yuri Dmitriev to be placed under house arrest for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until his court case is over. The petition can be signed in Russian, English, French, Italian, German, Hebrew, Polish, Czech, and Finnish. It can be found here and here. This is the second petition for Yuri Dmitriev. The first, from 2017, can be found here. Please find below: (1) a NCH case summary (2) the petition text in English. P.S. Another historian, Sergei Koltyrin – who had defended Yuri Dmitriev and was subsequently imprisoned under charges similar to his – died in a prison hospital in Medvezhegorsk, Karelia, on 2 April 2020. Please sign the petition immediately. ========== NCH CASE SUMMARY On 13 December 2016, the Federal Security Service (FSB) arrested Karelian historian Yuri Dmitriev (1956–) and held him in remand prison on charges of “preparing and circulating child pornography” and “depravity involving a minor [his foster child, eleven or twelve years old in 2017].” The arrest came after an anonymous tip: the individual and his motives, as well as how he got the private information, remain unknown. Dmitriev said the “pornographic” photos of his foster child were taken because medical workers had asked him to monitor the health and development of the girl, who was malnourished and unhealthy when he and his wife took her in at age three with the intention of adopting her. -

White Collar Criminality: a Prediction Model Judith M

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 White collar criminality: a prediction model Judith M. Collins Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Judith M., "White collar criminality: a prediction model " (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 9607. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/9607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2015 Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1490 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2625217 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1156-1239 (2015) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod EVIEW R ABSTRACT This Article introduces to legal scholarship the first sustained discussion of prison LA LAW LA LAW C abolition and what I will call a “prison abolitionist ethic.” Prisons and punitive policing U produce tremendous brutality, violence, racial stratification, ideological rigidity, despair, and waste. Meanwhile, incarceration and prison-backed policing neither redress nor repair the very sorts of harms they are supposed to address—interpersonal violence, addiction, mental illness, and sexual abuse, among others. Yet despite persistent and increasing recognition of the deep problems that attend U.S. incarceration and prison- backed policing, criminal law scholarship has largely failed to consider how the goals of criminal law—principally deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retributive justice—might be pursued by means entirely apart from criminal law enforcement. Abandoning prison-backed punishment and punitive policing remains generally unfathomable. This Article argues that the general reluctance to engage seriously an abolitionist framework represents a failure of moral, legal, and political imagination. -

Effects of Human Disturbance on Terrestrial Apex Predators

diversity Review Effects of Human Disturbance on Terrestrial Apex Predators Andrés Ordiz 1,2,* , Malin Aronsson 1,3, Jens Persson 1 , Ole-Gunnar Støen 4, Jon E. Swenson 2 and Jonas Kindberg 4,5 1 Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-730 91 Riddarhyttan, Sweden; [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (J.P.) 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Postbox 5003, NO-1432 Ås, Norway; [email protected] 3 Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden 4 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, NO-7485 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] (O.-G.S.); [email protected] (J.K.) 5 Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-901 83 Umeå, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The effects of human disturbance spread over virtually all ecosystems and ecological communities on Earth. In this review, we focus on the effects of human disturbance on terrestrial apex predators. We summarize their ecological role in nature and how they respond to different sources of human disturbance. Apex predators control their prey and smaller predators numerically and via behavioral changes to avoid predation risk, which in turn can affect lower trophic levels. Crucially, reducing population numbers and triggering behavioral responses are also the effects that human disturbance causes to apex predators, which may in turn influence their ecological role. Some populations continue to be at the brink of extinction, but others are partially recovering former ranges, via natural recolonization and through reintroductions. -

Nigeria's Renewal: Delivering Inclusive Growth in Africa's Largest Economy

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering renewal: Nigeria’s inclusive largest growth economy in Africa’s July 2014 Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering inclusive growth in Africa’s largest economy The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labour markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanisation. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI partners. Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

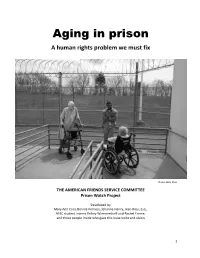

Aging in Prison a Human Rights Problem We Must Fix

Aging in prison A human rights problem we must fix Photo: Nikki Khan THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Prison Watch Project Developed by Mary Ann Cool, Bonnie Kerness, Jehanne Henry, Jean Ross, Esq., AFSC student interns Kelsey Wimmershoff and Rachel Frome, and those people inside who gave this issue voice and vision 1 Table of contents 1. Overview 3 2. Testimonials 6 3. Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey 11 4. Acknowledgements 13 2 Overview The population of elderly prisoners is on the rise The number and percentage of elderly prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically in past decades. In the year 2000, prisoners age 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population. Today, they are about 16 percent of that population. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of prisoners age 65 and older increased by an alarming 63 percent, compared to a 0.7 percent increase of the overall prison population. At this rate, prisoners 55 and older will approach one-third of the total prison population by the year 2030.1 What accounts for this rise in the number of elderly prisoners? The rise in the number of older people in prisons does not reflect an increased crime rate among this population. Rather, the driving force for this phenomenon has been the “tough on crime” policies adopted throughout the prison system, from sentencing through parole. In recent decades, state and federal legislators have increased the lengths of sentences through mandatory minimums and three- strikes laws, increased the number of crimes punished with life and life-without-parole and made some crimes ineligible for parole. -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

The Suppression of Communism Act

The Suppression of Communism Act http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1972_07 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Suppression of Communism Act Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 7/72 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Yengwa, Massabalala B. Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1972-03-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1972 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. Criticism of Bill in Parliament and by the Bar. The real purpose of the Act. -

The Political Construction of Collective Insecurity: from Moral Panic To

Center for European Studies Working Paper Series 126 (October 2005) The Political Construction of Collective Insecurity: From Moral Panic to Blame Avoidance and Organized Irresponsibility by Daniel Béland Department of Sociology University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4 Fax: (403) 282-9298 E-mail: [email protected]; web page: http://www.danielbeland.org/ Abstract This theoretical contribution explores the role of political actors in the social construction of collective insecurity. Two parts comprise the article. The first one briefly defines the concept of collective insecurity and the second one bridges existing sociological and political science literatures relevant for the analysis of the politics of insecurity. This theoretical framework articulates five main claims. First, although interesting, the concept of moral panic applies only to a limited range of insecurity episodes. Second, citizens of contemporary societies exhibit acute risk awareness and, when new collective threats emerge, the logic of “organized irresponsibility” often leads citizens and interest groups alike to blame elected officials. Third, political actors mobilize credit claiming and blame avoidance strategies to respond to these threats in a way that enhances their position within the political field. Fourth, powerful interests and institutional forces as well as the “threat infrastructure” specific to a policy area create constraints and opportunities for these strategic actors. Finally, their behavior is proactive or reactive, as political actors can either help push a threat onto the agenda early, or, at a later stage, simply attempt to shape the perception of this threat after other forces have transformed it into a major political issue. -

Prisons in Yemen

[PEACEW RKS [ PRISONS IN YEMEN Fiona Mangan with Erica Gaston ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines the prison system in Yemen from a systems perspective. Part of a three-year United States Institute of Peace (USIP) rule of law project on the post-Arab Spring transition period in Yemen, the study was supported by the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Bureau of the U.S. State Department. With permission from the Yemeni Ministry of Interior and the Yemeni Prison Authority, the research team—authors Fiona Mangan and Erica Gaston for USIP, Aiman al-Eryani and Taha Yaseen of the Yemen Polling Center, and consultant Lamis Alhamedy—visited thirty-seven deten- tion facilities in six governorates to assess organizational function, infrastructure, prisoner well-being, and security. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Fiona Mangan is a senior program officer with the USIP Governance Law and Society Center. Her work focuses on prison reform, organized crime, justice, and security issues. She holds degrees from Columbia University, King’s College London, and University College Dublin. Erica Gaston is a human rights lawyer with seven years of experience in programming and research in Afghanistan on human rights and justice promotion. Her publications include books on the legal, ethical, and practical dilemmas emerging in modern conflict and crisis zones; studies mapping justice systems and outcomes in Afghanistan and Yemen; and thematic research and opinion pieces on rule of law issues in transitioning countries. She holds degrees from Stanford University and Harvard Law School. Cover photo: Covered Yard Area, Hodeida Central. Photo by Fiona Mangan. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. -

Food in Prison: an Eighth Amendment Violation Or Permissible Punishment?

University of South Dakota USD RED Honors Thesis Theses, Dissertations, and Student Projects Spring 2020 Food In Prison: An Eighth Amendment Violation or Permissible Punishment? Natasha M. Clark University of South Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://red.library.usd.edu/honors-thesis Part of the Courts Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Natasha M., "Food In Prison: An Eighth Amendment Violation or Permissible Punishment?" (2020). Honors Thesis. 109. https://red.library.usd.edu/honors-thesis/109 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Student Projects at USD RED. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis by an authorized administrator of USD RED. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD IN PRISON: AN EIGHTH AMENDMENT VIOLATION OR PERMISSIBLE PUNISHMENT? By Natasha Clark A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the University Honors Program Department of Criminal Justice The University of South Dakota Graduation May 2020 The members of the Honors Thesis Committee appointed to examine the thesis of Natasha Clark find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. Professor Sandy McKeown Associate Professor of Criminal Justice Director of the Committee Professor Thomas Horton Professor & Heidepriem Trial Advocacy Fellow Dr. Thomas Mrozla Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice ii ABSTRACT FOOD IN PRISON: AN EIGHTH AMENDMENT VIOLATION OR PERMISSIBLE PUNISHMENT? Natasha Clark Director: Prof. Sandy McKeown, Associate Professor of Criminal Justice This piece analyzes aspects such as; Eighth Amendment provisions, penology, case law, privatization and monopoly, and food law, that play into the constitutionality of privatized prisons using food as punishment.