Some Economic Aspects of the Sheep Industg in the West of England Report No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No. 2) Order 2004 Made - - - - 6th December 2004 Laid before Parliament 10th December 2004 Coming into force - - 31st December 2004 The First Secretary of State, having received a report from the Audit Commission(a) produced under section 99(1) of the Local Government Act 2003(b), in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 99(4) of that Act, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No.2) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 31st December 2004. (2) This Order applies in relation to English local authorities(c). Categorisation report 2. The English local authorities, to which the report of the Audit Commission dated 8th November 2004 relates, are, by this Order, categorised in accordance with their categorisation in that report. Excellent authorities 3. The local authorities listed in Schedule 1 to this Order are categorised as excellent. Good authorities 4. The local authorities listed in Schedule 2 to this Order are categorised as good. Fair authorities 5. The local authorities listed in Schedule 3 to this Order are categorised as fair. (a) For the definition of “the Audit Commission”, see section 99(7) of the Local Government Act 2003. (b) 2003 c.26. The report of the Audit Commission consists of a letter from the Chief Executive of the Audit Commission to the Minister for Local and Regional Government dated 8th November 2004 with the attached list of local authorities categorised by the Audit Commission as of that date. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

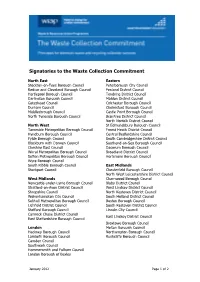

Waste Collection Commitment Signatories

Signatories to the Waste Collection Commitment North East Eastern Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council Peterborough City Council Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council Fenland District Council Hartlepool Borough Council Tendring District Council Darlington Borough Council Maldon District Council Gateshead Council Colchester Borough Council Durham Council Chelmsford Borough Council Middlesbrough Council Castle Point Borough Council North Tyneside Borough Council Braintree District Council North Norfolk District Council North West St Edmundsbury Borough Council Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Forest Heath District Council Hyndburn Borough Council Central Bedfordshire Council Fylde Borough Council South Cambridgeshire District Council Blackburn with Darwen Council Southend-on-Sea Borough Council Cheshire East Council Dacorum Borough Council Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Broadland District Council Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council Hertsmere Borough Council Wyre Borough Council South Ribble Borough Council East Midlands Stockport Council Chesterfield Borough Council North West Leicestershire District Council West Midlands Charnwood Borough Council Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Blaby District Council Stratford-on-Avon District Council West Lindsey District Council Shropshire Council North Kesteven District Council Wolverhampton City Council South Holland District Council Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council Boston Borough Council Lichfield District Council South Kesteven District Council Stafford Borough Council Lincoln City -

Highways England Region County Area LPA Regional Inbox

Highways England region County area LPA Regional inbox East Bedfordshire Central Bedfordshire [email protected] East Bedfordshire Luton Borough [email protected] East Bedfordshire Bedford Borough [email protected] South East Berkshire Slough BC [email protected] South East Berkshire West Berkshire District Council [email protected] South East Berkshire Royal Borough of Windsor and [email protected] South East Berkshire Maidenhead [email protected] South East Berkshire Reading Borough Council [email protected] South East Berkshire Wokingham District Council [email protected] South East Berkshire Bracknell Forest District Council [email protected] Midlands Black Country Dudley [email protected] Midlands Black Country Sandwell [email protected] Midlands Black Country Walsall [email protected] Midlands Black Country City of Wolverhampton [email protected] East Buckinghamshire Buckinghamshire County [email protected] East Buckinghamshire Milton Keynes (unitary) [email protected] East Buckinghamshire Chiltern District [email protected] South East Buckinghamshire Wycombe District [email protected] East Buckinghamshire Aylesbury Vale District [email protected] South East Buckinghamshire South Buckinghamshire District [email protected] East Cambridgeshire -

104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Somerset Geology-A Good Rock Guide

SOMERSET GEOLOGY-A GOOD ROCK GUIDE Hugh Prudden The great unconformity figured by De la Beche WELCOME TO SOMERSET Welcome to green fields, wild flower meadows, farm cider, Cheddar cheese, picturesque villages, wild moorland, peat moors, a spectacular coastline, quiet country lanes…… To which we can add a wealth of geological features. The gorge and caves at Cheddar are well-known. Further east near Frome there are Silurian volcanics, Carboniferous Limestone outcrops, Variscan thrust tectonics, Permo-Triassic conglomerates, sediment-filled fissures, a classic unconformity, Jurassic clays and limestones, Cretaceous Greensand and Chalk topped with Tertiary remnants including sarsen stones-a veritable geological park! Elsewhere in Mendip are reminders of coal and lead mining both in the field and museums. Today the Mendips are a major source of aggregates. The Mesozoic formations curve in an arc through southwest and southeast Somerset creating vales and escarpments that define the landscape and clearly have influenced the patterns of soils, land use and settlement as at Porlock. The church building stones mark the outcrops. Wilder country can be found in the Quantocks, Brendon Hills and Exmoor which are underlain by rocks of Devonian age and within which lie sunken blocks (half-grabens) containing Permo-Triassic sediments. The coastline contains exposures of Devonian sediments and tectonics west of Minehead adjoining the classic exposures of Mesozoic sediments and structural features which extend eastward to the Parrett estuary. The predominance of wave energy from the west and the large tidal range of the Bristol Channel has resulted in rapid cliff erosion and longshore drift to the east where there is a full suite of accretionary landforms: sandy beaches, storm ridges, salt marsh, and sand dunes popular with summer visitors. -

RFI2647 Your Ref: FOI Request – Minimum Geography Areas (Mgas) Tel: 0300 1234 500 Email: [email protected]

Date: 09/04/19 Our Ref: RFI2647 Your Ref: FOI Request – Minimum Geography Areas (MGAs) Tel: 0300 1234 500 Email: [email protected] Windsor House By Email Only 50 Victoria Street London SW1H 0TL Dear RE: Request for Information – RFI2647 Thank you for your request for information, which was processed under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). For clarification, you requested the following information: I am a researcher analysing published HCA/HE data on Affordable Housing Programme funding by area. I attach a spreadsheet including sheets for successive outputs relating to the year ending March 2014, 2017 and 2018. The first two appear to be for the Operating Areas HE inherited from HCA and the 2018 data is for the adjusted HE Operating Areas effective from 2017. The final, fourth sheet lists my understanding of the match between 326 English metropolitan, unitary, London and lower-tier districts. My FOI enquiry relates to HCA/HE Minimum Geography areas (MGAs), which is the lowest reporting geography you appear to use. The 2014 funding sheet lists 58 MGAs, the 2017 sheet 53 MGAs and the 2018 sheet 69 MGAs. It is not possible to impute or infer the geographic coverage of successive MGAs based on their description; and nor was it possible to identify this from an internet search. My FOI request is therefore for HE to provide a lookup or equivalent table listing each/any MGA used by HCA/HE since this reporting geography was first used, together with their constituent local authorities. Or to populate the final sheet of 326 local authorities by the MGA they form part of. -

Putley Court Lodge, Putley, Ledbury, Herefordshire

Putley Court Lodge, Putley, Ledbury, Herefordshire +4 Acres A beautiful detached period house set within an idyllic rural location LOCATION Ledbury 5 miles, Hereford 11.5 miles, Ross-on-Wye 13 miles, Malvern 13.5 miles, Worcester 22 miles, Cheltenham 31 miles Approximate Gross Internal Area E Main House = 1962 Sq Ft/182 Sq M S Workshop Road: M50 (Jct 2) 10.5 miles, M5 (Jct 8) 21 miles 3.4m x 2.9m 11'3" x 9'7" N Railway: Ledbury, Hereford, Malvern, Worcester W SUMMARY OF FEATURES: Garage Balcony 5.9m x 3.5m • Dating back to the 1800s, Putley Court Lodge is a stunning 19'2" x 11'5" 5.7m x 3.3m family home which has been extended to provide spacious 18'6" x 10'9" accommodation (1,962 ft sq). Sitting Room Master Bedroom • 4 bedrooms, 2 with en-suite facilities; Master with vaulted ceiling 5.6m x 3.6m 3.8m x 3.6m 18'6" x 11'9" 12'6" x 11'9" and fully-glazed end gable wall with double doors out to balcony Cellar enjoying fabulous views over the garden. Family bathroom. • Country-style fitted kitchen/breakfast room with Belfast sink and solid wood work surfaces. Utility room and cellar. • 3 reception rooms; sitting room with fully-glazed end gable Dining Room 3.6m x 2.4m wall and double doors leading out to the garden. 11'11" x 8'0" In all +4 Acres Kitchen 3.6m x 3.2m Bedroom 4 11'8" x 10'7" Hatch 3.6m x 2.6m SITUATION To Cellar Snug 11'8" x 8'4" Bedroom 3 3.9m x 3.6m Bedroom 2 3.6m x 2.6m The small rural parish of Putley is situated within the beautiful 12'11" x 11'9" 3.6m x 3.1m 11'10" x 8'8" Herefordshire countryside. -

![HEREFORDSHIRE. [KELLY's DIRECTORY.] YATTON Is a Chapelry and Township in Much Marcle Calne, Wilts, and L:Aeld Since X8g6 by the Rev](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0010/herefordshire-kellys-directory-yatton-is-a-chapelry-and-township-in-much-marcle-calne-wilts-and-l-aeld-since-x8g6-by-the-rev-1410010.webp)

HEREFORDSHIRE. [KELLY's DIRECTORY.] YATTON Is a Chapelry and Township in Much Marcle Calne, Wilts, and L:Aeld Since X8g6 by the Rev

210 1"ATTON•. HEREFORDSHIRE. [KELLY'S DIRECTORY.] YATTON is a chapelry and township in Much Marcle Calne, Wilts, and l:aeld since x8g6 by the Rev. Cecil parish, on the old road from Led'bury to Ross, s miles Leigh Money-Kyrle M.A. of Oriel College, Oxford, who south-west from Fawley station on the Hereford, Ross 1·esides at Much Marcle. The principal landowner is and Gloucester section of the Great Western railway, Gen. Edward Henry Olive, of Perrystone Court, Foy. 8 eout.h-west from Ledbury, 5 east from Boss, o.nd in The soil is principally heavy; subsoil, clay. The chief the Southern division of the county, Greytree hundred. crops are wheat, beans and peas. The area is 1,452 Boss onion, county court district and petty sessional acres; rateable value, £1,391; population in 1gn, rtio. division, rural deanery of Boss and archdeaconry and Parish Clerk, Claud Davis. di00011e of Hereford. The chapel, erected about 1'll3o, Post Office, Perrystone Hill.-Mrs. Anna Brown, sub is a crucifonn building of white atone in t:Jhe Early postmistress. Letters through Ross arrive at; 7 a.m. Engli$11 style, consisting of chancel, nave, north and & 2.50 p.m.; dispatched 3·45 & 5.30 p.m. ; no delivery south transepts and a western entrance and turret con on sunday. Upton Bishop is the nearest money order taining one bell : the chapel was restored and a chancel office & How Caple, 2 miles distant, the nearest tele added in 1904, in memory of the late Sybella, Lady graph office Lyttelton, of The Chantry. -

2019 Mid Devon Show Results

2019 Mid Devon Show Results 1 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN - Maiden Heifer 1st M Harris 2nd CRJ & JA Bishop 3rd W Neale 4th S Phillips 2 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN - Heifer in-calf 1st M Harris 3 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN - Cow in-calf No Entries 4 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN - Heifer in-milk 1st R Reed 2nd FH Chave & Son 3rd R Reed 5 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN - Cow in-milk,second or subsequent lactation 1st R Reed 2nd FH Chave & Son 3rd R Reed C1 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN Champion R Reed Reserve FH Chave & Son C2 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN (Devon Holstein Club) Champion R Reed C2 HOLSTEIN FRIESIAN (Champion in-milk) Champion R Reed 6 AYRSHIRE - Maiden Heifer 1st CRJ & JA Bishop 2nd A Mortimer 7 AYRSHIRE - Heifer in-calf 1st A Mortimer 8 AYRSHIRE - Cow in-calf No Entries 9 AYRSHIRE - Heifer in-milk No Entries 10 AYRSHIRE - Cow in-milk, second or subsequent lactation 1st J Cornish & Sons C21 AYRSHIRE Champion J Cornish & Sons Reserve A Mortimer 11 GUERNSEY - Maiden Heifer 1st S Phillips 12 GUERNSEY - Heifer in-calf 1st S Phillips 13 GUERNSEY - Cow in-calf No Entries 14 GUERNSEY - Heifer in-milk No Entries 15 GUERNSEY - Cow in-milk, second or subsequent lactation No Entries C5 GUERNSEY Champion S Phillips Reserve S Phillips 16 JERSEY - Maiden Heifer 1st The Davis Family 2nd S Phillips 3rd S Phillips 17 JERSEY - Heifer in-calf No Entries 18 JERSEY - Cow in-calf No Entries 19 JERSEY - Heifer in-milk 1st The Davis Family 2nd The Davis Family 20 JERSEY - Cow in-milk, second or subsequent lactaion 1st The Davis Family 2nd The Davis Family C4 JERSEY Champion The Davis Family Reserve The Davis Family 21 ANY -

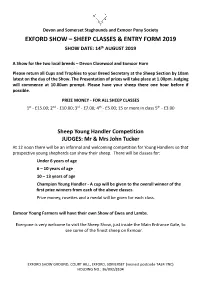

Sheep Classes & Entry Form 2019

Devon and Somerset Staghounds and Exmoor Pony Society EXFORD SHOW – SHEEP CLASSES & ENTRY FORM 2019 SHOW DATE: 14th AUGUST 2019 A Show for the two local breeds – Devon Closewool and Exmoor Horn Please return all Cups and Trophies to your Breed Secretary at the Sheep Section by 10am latest on the day of the Show. The Presentation of prizes will take place at 1.00pm. Judging will commence at 10.00am prompt. Please have your sheep there one hour before if possible. PRIZE MONEY - FOR ALL SHEEP CLASSES 1st - £15.00; 2nd - £10.00; 3rd - £7.00; 4th - £5.00; 15 or more in class 5th - £3.00 Sheep Young Handler Competition JUDGES: Mr & Mrs John Tucker At 12 noon there will be an informal and welcoming competition for Young Handlers so that prospective young shepherds can show their sheep. There will be classes for: Under 6 years of age 6 – 10 years of age 10 – 13 years of age Champion Young Handler - A cup will be given to the overall winner of the first prize winners from each of the above classes. Prize money, rosettes and a medal will be given for each class. Exmoor Young Farmers will have their own Show of Ewes and Lambs. Everyone is very welcome to visit the Sheep Show, just inside the Main Entrance Gate, to see some of the finest sheep on Exmoor. EXFORD SHOW GROUND, COURT HILL, EXFORD, SOMERSET (nearest postcode TA24 7NC) HOLDING NO.: 36/092/8104 Devon and Somerset Staghounds and Exmoor Pony Society EXMOOR HORN JUDGE: Mr Edward Harding Breed Secretary: Mrs Jan Brown All classes confined to sheep registered in their respective Flock Book. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found.