The Memetic Evolution of Alchemy from Zosimos to Timothy Leary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Redalyc.Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII Th–XIX Th Centuries

REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña E-ISSN: 1659-4223 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Khalturin, Yuriy Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII th–XIX th centuries REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 7, núm. 1, mayo-noviembre, 2015, pp. 128-140 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369539930009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, Vol. 7, no. 2, Mayo - Noviembre 2015/ 128-140 128 Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysics in Russian Freemasonry of the XVIIIth – XIXth centuries Yuriy Khalturin PhD in Philosophy (Russian Academy of Science), independent scholar, member of ESSWE. E-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recibido: 20 de noviembre de 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 8 de enero de 2015 Palabras clave Cábala, masonería, rosacrucismo, teosofía, sofilogía, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanación, alquimia, la estrella llameante, columnas Jaquín y Boaz Keywords Kabbalah, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Sophiology, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanation, alchemy, Flaming Star, Columns Jahin and Boaz Resumen Este trabajo considera algunas conexiones entre la Cábala y la masonería en Rusia como se refleja en los archivos del Departamento de Manuscritos de la Biblioteca Estatal Rusa (DMS RSL). El vínculo entre ellos se basa en la comprensión tanto de la Cabala y la masonería como la filosofía simbólica y “verdaderamente metafísica”. -

Rosicrucianism from Its Origins to the Early 18Th Century

CHAPTER TWO ROSICRUCIANISM FROM ITS ORIGINS TO THE EARLY 18TH CENTURY In order to understand the 18th-century Rosicrucian revival it is necessary to know something of the origins and early history of Rosicrucianism. This ground has already been covered many times,1 but it is worth covering it again here in broad outline as a prelude to my main investigation. The Rosicrucian legend was born in the early 17th century in the uneasy period before religious tensions in Central Europe erupted into the Thirty Years' War. The Lutheran Reformation of a century earlier had finally shat tered the religious unity of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. On the other hand, as the historian Geoffrey Parker has observed, the Reformation had not produced the spiritual renewal that its advocates had hoped for.2 In the prevailing atmosphere of political and religious tension and spiritual malaise, many people turned, in their dismay, to the old millenarian dream of a new age. This way of thinking, dating back to the writings of the 12th-cen tury Calabrian abbot Joachim of Fiore, had surfaced at various times in the intervening centuries, giving rise to movements of the kind described by Nor man Cohn in his Pursuit of the Millennium3 and by Marjorie Reeves in her Joachim ofFiore and the Prophetic Future.4 Joachim and his followers saw history as unfolding in a series of three ages, corresponding to the three per sons of the Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in that order. They believed that hitherto they had been living in the Age of the Son, but that the Age of the Spirit was at hand. -

Rosicrucianism in the Contemporary Period in Denmark

Contemporary Rosicrucianism in Denmark 445 Chapter 55 Contemporary Rosicrucianism in Denmark Rosicrucianism in the Contemporary Period in Denmark Jacob Christiansen Senholt Rosicrucian ideas were present in Denmark already during the seventeenth century, fuelled by the publication of the tracts Fama fraternitatis rosae crucis and Confessio fraternitatis in Germany in 1614 and 1615 respectively. After a gap in the history of Rosicrucian presence in Denmark of almost 300 years, modern Rosicrucian societies spread across the world, and following this wave of Rosi cru cian fraternities, Danish offshoots of these fraternities also emerged. The modernday Rosicrucians and their presence in Denmark stem from two differ ent historical roots. The first is an influence from Germany via the Rosicrucian Society in Germany (RosenkreuzerGesellschaft in Deutschland), and the other comes from the United States, with the formation of Antiquus Mys ti cus que Ordo Rosæ Crucis (AMORC) by Harvey Spencer Lewis (1883–1939) in 1915. The Rosicrucian Fellowship The history of modern Rosicrucianism in Denmark starts in 1865 when Carl Louis von Grasshoff (1865–1919), later known under the pseudonym Max Heindel, was born. Although born in Denmark, Heindel was of German ances try, and spent most of his life travelling in both the United States and Germany. He was a member of the Theosophical Society and met with the later founder of Anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner, in 1907. In 1909 he published his major work, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, which dealt with Christian mysticism and esotericism, and later that year Heindel founded The Rosicrucian Fellowship. It was a German spinoff of this group lead by occultist and theosophist Franz Hartmann (1838–1912) and later Hugo Vollrath, that later became influential in Denmark. -

Book Reviews

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 35, Number 2 (2010) 125 BOOK REVIEWS Rediscovery of the Elements. James I. and Virginia Here you can find mini-biographies of scientists, R. Marshall. JMC Services, Denton TX. DVD, Web detailed geographic routes to each of the element discov- Page Format, accessible by web browsers and current ery sites, cities connected to discoveries, maps (354 of programs on PC and Macintosh, 2010, ISBN 978-0- them) and photos (6,500 from a base of 25,000), a time 615-30793-0. [email protected] $60.00 line of discoveries, 33 background articles published by ($50.00 for nonprofit organizations {schools}, $40.00 the authors in The Hexagon, and finally a link to “Tables at workshops.) and Text Files,” a compilation probably containing more information than all the rest of the DVD. I will discuss this later, except for one file in it: “Background Before the launching of this review it needs to be and Scope.” Here the authors point out that the whole stated that DVDs are not viewable unless your computer project of visiting the sources, mines, quarries, museums, is equipped with a DVD reader. I own a 2002 Microsoft laboratories connected with each element, only became Word XP computer, but it failed. I learned that I needed possible very recently. Four recent developments opened a piece of hardware, a DVD reader. It can be installed the door: first, the fall of the Iron Curtain allowing easy inside the computer or attached externally. The former is access to Eastern Europe including Russia; second, the cheaper, in fact quite inexpensive, unless you have to pay universality of email and internet communication; third, for the installation. -

The Writings of Marsilio Ficino and Lodovico Lazzarelli

Iskander Israel Rocha Parker CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF HERMETIC THOUGHT IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ITALY: THE WRITINGS OF MARSILIO FICINO AND LODOVICO LAZZARELLI MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. Central European University Budapest June 2020 CEU eTD Collection CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF HERMETIC THOUGHT IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ITALY: THE WRITINGS OF MARSILIO FICINO AND LODOVICO LAZZARELLI by Iskander Israel Rocha Parker (Mexico) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest Month YYYY CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF HERMETIC THOUGHT IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ITALY: THE WRITINGS OF MARSILIO FICINO AND LODOVICO LAZZARELLI by Iskander Israel Rocha Parker (Mexico) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. Accepted in conformance -

Theosophical Siftings Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians Vol 6, No 15 Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians

Theosophical Siftings Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians Vol 6, No 15 Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians by William Wynn Westcott Reprinted from "Theosophical Siftings" Volume 6 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England [Page 3] THE Rosicrucians of mediaeval Germany formed a group of mystic philosophers, assembling, studying and teaching in private the esoteric doctrines of religion, philosophy and occult science, which their founder, Christian Rosenkreuz, had learned from the Arabian sages, who were in their turn the inheritors of the culture of Alexandria. This great city of Egypt, a chief emporium of commerce and a centre of intellectual learning, flourished before the rise of the Imperial power of Rome, falling at length before the martial prowess of the Romans, who, having conquered, took great pains to destroy the arts and sciences of the Egypt they had overrun and subdued ; for they seem to have had a wholesome fear of those magical arts, which, as tradition had informed them, flourished in the Nile Valley; which same tradition is also familiar to English people through our acquaintance with the book of Genesis, whose reputed author was taught in Egypt all the science and arts he possessed, even as the Bible itself tells us, although the orthodox are apt to slur over this assertion of the Old Testament narrative. Our present world has taken almost no notice of the Rosicrucian philosophy, nor until the last twenty years of any mysticism, and when it does condescend to stoop from its utilitarian and money-making occupations, it is only to condemn all such studies, root and branch, as waste of time and loss of energy. -

Agrippa's Cosmic Ladder: Building a World with Words in the De Occulta Philosophia

chapter 4 Agrippa’s Cosmic Ladder: Building a World with Words in the De Occulta Philosophia Noel Putnik In this essay I examine certain aspects of Cornelius Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia libri tres (Three Books of Occult Philosophy, 1533), one of the foun- dational works in the history of western esotericism.1 To venture on a brief examination of such a highly complex work certainly exceeds the limitations of an essay, but the problem I intend to delineate, I believe, can be captured and glimpsed in its main contours. I wish to consider the ways in which the German humanist constructs and represents a common Renaissance image of the universe in his De occulta philosophia. This image is of pivotal importance for understanding Agrippa’s peculiar worldview as it provides a conceptual framework in which he develops his multilayered and heterodox thought. In other words, I deal with Agrippa’s cosmology in the context of his magical the- ory. The main conclusion of my analysis is that Agrippa’s approach to this topic is remarkably non-visual and that his symbolism is largely of verbal nature, revealing an author predominantly concerned with the nature of discursive language and the linguistic implications of magical thinking. The De occulta philosophia is the largest, most important, and most complex among the works of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535). It is a summa of practically all the esoteric doctrines and magical practices ac- cessible to the author. As is well known and discussed in scholarship, this vast and diverse amount of material is organized within a tripartite structure that corresponds to the common Neoplatonic notion of a cosmic hierarchy. -

John Dee, Willem Silvius, and the Diagrammatic Alchemy of the Monas Hieroglyphica

The Royal Typographer and the Alchemist: John Dee, Willem Silvius, and the Diagrammatic Alchemy of the Monas Hieroglyphica Stephen Clucas Birkbeck, University of London, UK Abstract: John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica (1564) was a work which involved a close collaboration between its author and his ‘singular friend’ the Antwerp printer Willem Silvius, in whose house Dee was living whilst he composed the work and saw it through the press. This article considers the reasons why Dee chose to collaborate with Silvius, and the importance of the intellectual culture – and the print trade – of the Low Countries to the development of Dee’s outlook. Dee’s Monas was probably the first alchemical work which focused exclusively on the diagrammatic representation of the alchemical process, combining diagrams, cosmological schemes and various forms of tabular grid. It is argued that in the Monas the boundaries between typography and alchemy are blurred as the diagrams ‘anatomizing’ his hieroglyphic sign (the ‘Monad’) are seen as revealing truths about alchemical substances and processes. Key words: diagram, print culture, typography, John Dee, Willem Silvius, alchemy. Why did John Dee go to Antwerp in 1564 in order to publish his recondite alchemical work, the Monas Hieroglyphica? What was it that made the Antwerp printer Willem Silvius a suitable candidate for his role as the ‘typographical parent’ of Dee’s work?1 In this paper I look at the role that Silvius played in the evolution of Dee’s most enigmatic work, and at the ways in which Silvius’s expertise in the reproduction of printed diagrams enabled Dee to make the Monas one of the first alchemical works to make systematic use of the diagram was a way of presenting information about the alchemical process. -

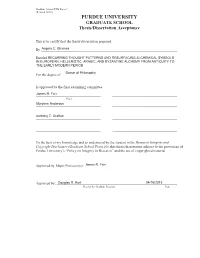

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Alchemylab Articles\374

Alchemical Theory The One Thing (or the Subtle Ether) Space, whether interplanetary, inner matter, or inter-organic, is filled with a subtle presence emanating from the One Thing of the universe. Later alchemists called it, as did the ancients, the subtle Ether. This primordial fluid or fabric of space pervades everything and all matter. Metal, mineral, tree, plant, animal, man; each is charged with the Ether in varying degrees. All life on the planet is charged in like manner; a world is built up in this fluid and move through a sea of it. Alchemical Ether, which some Hermeticists call the Astral Light, determines the constitution of bodies. Hardness and softness, solidity and liquidity, all depend on the relative proportion of ethereal and ponderable matter of which they me composed. The arbitrary division and classification of physical science, the whole range of physical phenomena, proceeds from the primary Ether, for science has reduced matter as we know it to nothing but Ether, which, although not solid matter, is still matter, the First Matter of the alchemists. When most of us speak of matter, of course, we usually visualize solid substance, but it has been proved by that matter is not actually solid, but merely a stress, a strain in the etheric field of time and space. The atom and the electrons and protons of which it is composed, all move in a sea of Ether, so, that in accordance with this theory of alchemy, the very air we breathe, the very bodies we inhabit, all things most likewise be moving in this sea of Ether, the parent element from which all manifestation has come. -

THE ETERNAL HERMES from Greek God to Alchemical Magus

THE ETERNAL HERMES From Greek God to Alchemical Magus With thirty-nine plates Antoine Faivre Translated by Joscelyn Godwin PHANES PRESS 1995 © 1995 by Antoine Faivre. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, with the exception of short excerpts used in reviews, without permission in writing from the publisher. Book and cover design by David Fideler. Phanes Press publishes many fine books on the philosophical, spiritual, and cosmological traditions of the Western world. To receive a complete catalogue, please write: Phanes Press, PO Box 6114, Grand Rapids, MI 49516, USA. Library 01 Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Faivre, Antoine, 1934- The eternal Hermes: from Greek god to alchemical magus / Antoine Faivre; translated by Joscelyn Godwin p. cm. Articles originally in French, published separately. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-933999-53-4 (alk. paper)- ISBN 0-933999-52-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Hennes (Greek deity) 2. Hermes, Trismegistus. 3. Hermetism History. 4. Alchemy-History. I. Title BL920.M5F35 1995 135'.4-<lc20 95-3854 elP Printed on permanent, acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 9998979695 5432 1 Contents Preface ................................................................................. 11 Chapter One Hermes in the Western Imagination ................................. 13 Introduction: The Greek Hermes ....................................................... 13 The Thrice-Greatest .......................................................