How Feed Requirements Change During Lactation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Hale's Lactation Risk Categories

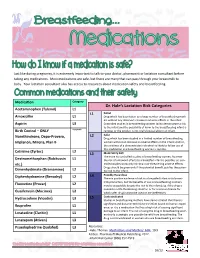

Just like during pregnancy, it is extremely important to talk to your doctor, pharmacist or lactation consultant before taking any medications. Most medications are safe, but there are many that can pass through your breastmilk to baby. Your lactation consultant also has access to resources about medication safety and breastfeeding. Medication Category Dr. Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories Acetaminophen (Tylenol) L1 L1 Safest Amoxicillin L1 Drug which has been taken by a large number of breastfeeding moth- ers without any observed increase in adverse effects in the infant. Aspirin L3 Controlled studies in breastfeeding women fail to demonstrate a risk to the infant and the possibility of harm to the breastfeeding infant is Birth Control – ONLY Acceptable remote; or the product is not orally bioavailable in an infant. L2 Safer Norethindrone, Depo-Provera, Drug which has been studied in a limited number of breastfeeding Implanon, Mirena, Plan B women without an increase in adverse effects in the infant; And/or, the evidence of a demonstrated risk which is likely to follow use of this medication in a breastfeeding woman is remote. Cetrizine (Zyrtec) L2 L3 Moderately Safe There are no controlled studies in breastfeeding women, however Dextromethorphan (Robitussin L1 the risk of untoward effects to a breastfed infant is possible; or, con- etc.) trolled studies show only minimal non-threatening adverse effects. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the poten- Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) L2 tial risk to the infant. L4 Possibly Hazardous Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) L2 There is positive evidence of risk to a breastfed infant or to breast- milk production, but the benefits of use in breastfeeding mothers Fluoxetine (Prozac) L2 may be acceptable despite the risk to the infant (e.g. -

Breastfeeding Is Best Booklet

SOUTH DAKOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH WIC PROGRAM Benefits of Breastfeeding Getting Started Breastfeeding Solutions Collecting and Storing Breast Milk Returning to Work or School Breastfeeding Resources Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine www.bfmed.org American Academy of Pediatrics www2.aap.org/breastfeeding Parenting website through the AAP www.healthychildren.org/English/Pages/default.aspx Breastfeeding programs in other states www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/CDC_BFWorkplaceSupport.pdf Business Case for Breastfeeding www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-home-work- and-public/breastfeeding-and-going-back-work/business-case Centers for Disease Control and Prevention www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm FDA Breastpump Information www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ HomeHealthandConsumer/ConsumerProducts/BreastPumps Healthy SD Breastfeeding-Friendly Business Initiative www.healthysd.gov/breastfeeding International Lactation Consultant Association www.ilca.org/home La Leche League www.lalecheleague.org MyPlate for Pregnancy and Breastfeeding www.choosemyplate.gov/moms-pregnancy-breastfeeding South Dakota WIC Program www.sdwic.org Page 1 Breastfeeding Resources WIC Works Resource System wicworks.fns.usda.gov/breastfeeding World Health Organization www.who.int/nutrition/topics/infantfeeding United States Breastfeeding Committee - www.usbreastfeeding.org U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/ Office of Women’s Health www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding -

Clinical Update and Treatment of Lactation Insufficiency

Review Article Maternal Health CLINICAL UPDATE AND TREATMENT OF LACTATION INSUFFICIENCY ARSHIYA SULTANA* KHALEEQ UR RAHMAN** MANJULA S MS*** SUMMARY: Lactation is beneficial to mother’s health as well as provides specific nourishments, growth, and development to the baby. Hence, it is a nature’s precious gift for the infant; however, lactation insufficiency is one of the explanations mentioned most often by women throughout the world for the early discontinuation of breast- feeding and/or for the introduction of supplementary bottles. Globally, lactation insufficiency is a public health concern, as the use of breast milk substitutes increases the risk of morbidity and mortality among infants in developing countries, and these supplements are the most common cause of malnutrition. The incidence has been estimated to range from 23% to 63% during the first 4 months after delivery. The present article provides a literary search in English language of incidence, etiopathogensis, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and current update on treatment of lactation insufficiency from different sources such as reference books, Medline, Pubmed, other Web sites, etc. Non-breast-fed infant are 14 times more likely to die due to diarrhea, 3 times more likely to die of respiratory infection, and twice as likely to die of other infections than an exclusively breast-fed child. Therefore, lactation insufficiency should be tackled in appropriate manner. Key words : Lactation insufficiency, lactation, galactagogue, breast-feeding INTRODUCTION Breast-feeding is advised becasue human milk is The synonyms of lactation insufficiency are as follows: species-specific nourishment for the baby, produces lactational inadequacy (1), breast milk insufficiency (2), optimum growth and development, and provides substantial lactation failure (3,4), mothers milk insufficiency (MMI) (2), protection from illness. -

Maternal Intake of Cow's Milk During Lactation Is Associated with Lower

nutrients Article Maternal Intake of Cow’s Milk during Lactation Is Associated with Lower Prevalence of Food Allergy in Offspring Mia Stråvik 1 , Malin Barman 1,2 , Bill Hesselmar 3, Anna Sandin 4, Agnes E. Wold 5 and Ann-Sofie Sandberg 1,* 1 Department of Biology and Biological Engineering, Food and Nutrition Science, Chalmers University of Technology, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (M.B.) 2 Institute of Environmental Medicine, Unit of Metals and Health, Karolinska Institutet, 171 77 Stockholm, Sweden 3 Department of Paediatrics, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Department of Clinical Science, Pediatrics, Sunderby Research Unit, Umeå University, 901 87 Umeå, Sweden; [email protected] 5 Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute of Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 413 90 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: ann-sofi[email protected] Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 28 November 2020 Abstract: Maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation may affect the propensity of the child to develop an allergy. The aim was to assess and compare the dietary intake of pregnant and lactating women, validate it with biomarkers, and to relate these data to physician-diagnosed allergy in the offspring at 12 months of age. Maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation was assessed by repeated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires in a prospective Swedish birth cohort (n = 508). Fatty acid proportions were measured in maternal breast milk and erythrocytes. Allergy was diagnosed at 12 months of age by a pediatrician specialized in allergy. -

Breastfeeding Support Credentials

Who’s Who? A glance at breastfeeding support in the United States Lactation support is often needed to help mothers initiate and continue breastfeeding. There are many kinds of help available for breastfeeding mothers including peer counselors, certified breastfeeding educators and counselors, and lactation professionals such as the International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC®). Breastfeeding support is valuable for a variety of reasons, from encouragement and emotional support to guidance and assistance with complex clinical situations. Mothers benefit from all kinds of support, and it is important to receive the right kind at the right time. The breastfeeding support categories listed below each play a vital role in providing care to mothers and babies. Breastfeeding Support Prerequisites Training Required Scope of Practice Type • 90 hours of lactation-specific education Recognized health Provide professional, • College level health science professional or evidence based, clinical courses Professional satisfactory completion lactation management; • 300-1000 clinical practice hours (International Board Certified of collegiate level educate families, health Lactation Consultant, IBCLC®) • Successful completion of a health sciences professionals and others criterion-referenced exam offered coursework. about human lactation. by an independent international board of examiners. Certified • 20-120 hours of classroom training Provide education and • Often includes a written exam guidance for families (i.e. Certified Lactation N/A Counselor, Certified or “certification” offered by the on basic breastfeeding Breastfeeding Educator, etc. ) training organization issues. Provide breastfeeding information, Peer Personal breastfeeding • 18-50 hours of classroom training encouragement, and (i.e. La Leche League, WIC experience. Peer Counselor, etc.) support to those in their community. Copyright © 2016 by USLCA. -

MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH Technical Information Bulletin

A Review of the Medical Benefits and Contraindications to Breastfeeding in the United States Ruth A. Lawrence, M.D. Technical Information Bulletin Technical MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH MATERNAL October 1997 Cite as Lawrence RA. 1997. A Review of the Medical Benefits and Contraindications to Breastfeeding in the United States (Maternal and Child Health Technical Information Bulletin). Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health. A Review of the Medical Benefits and Contraindications to Breastfeeding in the United States (Maternal and Child Health Technical Information Bulletin) is not copyrighted with the exception of tables 1–6. Readers are free to duplicate and use all or part of the information contained in this publi- cation except for tables 1–6 as noted above. Please contact the publishers listed in the tables’ source lines for permission to reprint. In accordance with accepted publishing standards, the National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health (NCEMCH) requests acknowledg- ment, in print, of any information reproduced in another publication. The mission of the National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health is to promote and improve the health, education, and well-being of children and families by leading a nation- al effort to collect, develop, and disseminate information and educational materials on maternal and child health, and by collaborating with public agencies, voluntary and professional organi- zations, research and training programs, policy centers, and others to advance knowledge in programs, service delivery, and policy development. Established in 1982 at Georgetown University, NCEMCH is part of the Georgetown Public Policy Institute. NCEMCH is funded primarily by the U.S. -

Journal of Human Lactation

Journal of Human Lactation http://jhl.sagepub.com Exclusive Breastfeeding: Isn’t Some Breastfeeding Good Enough? Jane Heinig and Kara Ishii J Hum Lact 2004; 20; NP DOI: 10.1177/089033440402000409 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jhl.sagepub.com Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: International Lactation Consultant Association Additional services and information for Journal of Human Lactation can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jhl.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jhl.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from http://jhl.sagepub.com at International Lactation Consultant Association on September 29, 2008 ILCA’s INSIDE TRACK a resource for breastfeeding mothers A Publication of the International Lactation Consultant Association Exclusive Breastfeeding: Isn’t Some Breastfeeding Good Enough? By Jane Heinig, PhD, IBCLC, and Kara Ishii, MSW ongratulations on choosing to for at least 3 months. For mothers, exclusive breastfeed your baby! As you know, breastfeeding during the first 6 months means Cmany of the benefits of breastfeeding that more calories are going to make milk (so last a lifetime. You might have heard that health the mother loses weight more quickly, which is organizations, including the World Health Orga- important for her health). Also, mothers who nization, recommend exclusive breastfeeding for exclusively breastfeed often go 9 months with- the first 6 months of life. You may be wondering out a period after their babies are born. Longer if exclusive breastfeeding is truly important or if breastfeeding is also related to greater protec- breastfeeding mixed with bottle feeding is just tion for mothers against breast cancer. -

Factors Affecting Goat Milk Production and Quality

Small Ruminant Research 101 (2011) 55–63 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Small Ruminant Research jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/smallrumres Review article ଝ Factors affecting goat milk production and quality ∗ A.L. Goetsch , S.S. Zeng, T.A. Gipson American Institute for Goat Research, Langston University, P. O. Box 1730, Langston, OK 73050, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Differences between production systems based on grazing and browsing vs. use of har- Available online 5 October 2011 vested feedstuffs in confinement largely depend on specific feedstuffs and plants available and being consumed. Low forage nutrient ingestion should have relatively greater impact Keywords: on tissue mobilization than milk production in early than later periods of lactation, with a Goats transition to proportionally greater change in milk production in late lactation. However, Milk low body condition at kidding would limit tissue energy mobilization and restrict impact Lactation of level of nutrient intake to milk yield and, likewise, tissue mobilization would be less with one vs. two or three milkings per day. As lactation advances after freshening, fat and protein levels decrease with increasing milk yield, and when production declines in mid- to late lactation, fat and protein concentrations increase. Milk production generally peaks at a parity of 3 or 4, thereafter declining slowly. Elevated somatic cell count alone in dairy goats is not a valid indication of mammary infection. Extended lactations offer opportunities to minimize or avoid seasonal fluctuations in milk production and lessen production costs. -

Your Guide to Breastfeeding

Pumping and Milk Storage If you are unable to breastfeed your baby directly, it is important to remove milk during the times your baby normally would feed. This will help you continue to make milk. Before you express breast milk, be sure to wash your hands. Also, make sure the area where you are expressing is clean. If you need help to get your milk to start fow- ing, have one of the following items nearby – a picture of your baby, a baby blanket, or an item of your baby’s clothing that has his or her scent on it. You can also apply a warm moist compress to the breast, gently massage the breasts, or sit quietly and think of a relaxing setting. Ways to Express Your Milk Type How It Works What’s Involved Average Cost Hand You use your hand to UÊRequires practice, skill, and coordination. Free, unless you need Expression massage and com- UÊGets easier with practice; can be as fast as help from a breastfeeding press your breast to pumping. professional who charges remove milk. UÊGood if you are seldom away from baby or for her services. need an option that is always with you. But all moms should learn how to hand express. Manual Pump You use your hand UÊRequires practice, skill, and coordination. $30 to $50 and wrist to operate UÊUseful for occasional pumping if you are a hand-held device to away from baby once in a while. pump the milk. Automatic, Runs on battery or UÊCan be easier for some moms. -

Part 3 Breastfeeding and Infant Food Allergy

Breastfeeding and Infant Food Allergy Janice M. Joneja, Ph.D., RD Breast-feeding and Allergy Studies indicating that breast-feeding is protective against allergy report: – A definite improvement in infant eczema and associated gastrointestinal complaints when: •Baby is exclusively breast-fed • Mother eliminates food allergens from her diet – Reduced risk of asthma in the first 24 months of life 2 Breast-feeding and Allergy • Other studies are in conflict with these conclusions: – Some report no improvement in symptoms – Some suggest symptoms get worse with breast- feeding and improve with feeding of hydrolysate formulae – Japanese study suggests that breast-feeding increases the risk of asthma at adolescence • What is the real story? 3 Immune System of the Normal Neonate •Is immature • Major elements of the immune system are in place • But do not function at a level to provide adequate protection against infection • The level of immunoglobulins (except maternal IgG) is a fraction of that of the adult 4 Immune System of the Normal Neonate • Phagocytes can engulf foreign particles • But their killing capacity is negligible during the first 24 hours of life • The function of the lymphocytes is not fully developed • Human milk provides the deficient components 5 Development of Immunocompetence with Age % Adult Activity Birth 100 80 IgG IgM SIgA 60 IgA IgE 40 20 3 6 0.5 1 2 34567 86 Fetal age (months) 9 Age (years) Immunological Protection • Agents in human milk: – Provide passive protection of the infant against infection during lactation • Mother’s system provides the protective factors – Stimulate the immune system of the baby to provide active protection • Infant’s own system makes the protective factors – The effects may last long after weaning 7 Characteristics of Protective Factors Provided by Breastfeeding • Persist throughout lactation • Resist digestion in the infant’s digestive tract • Protect by non-inflammatory mechanisms • Stimulate maturation of the infant’s immune system • Are the same as at mucosal sites (e.g. -

The Use of Human Milk and Breastfeeding in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

The Use of Human Milk and Breastfeeding in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Position Statement #3065 NANN Board of Directors April 2015 The use of human milk and breastfeeding are essential components in providing optimal health for the critically ill newborn. As the professional voice of neonatal nurses, the National Association of Neonatal Nurses (NANN) encourages all neonatal nurses to provide mothers of critically ill newborns with the education, support, and encouragement needed to provide human milk for their infant. Association Position Human milk and breastfeeding are essential for the growth and development of the vulnerable infant. All infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months, with continued breastfeeding for a year or more. A top priority for neonatal nurses is to ensure that all families understand the unique role that human milk plays in the health of their child. It is the responsibility of neonatal nurses to provide all mothers with education about the benefits of human milk for their infants, regardless of the mothers’ original intentions regarding feeding, and to encourage them to express milk for as long as possible. Research by Hallowell and colleagues demonstrated that only 49% of NICUs had lactation consultants working in the NICU and that nurses only reported providing breastfeeding support 13% (median) of the time on their prior shift (Hallowell et al., 2014). Neonatal nurses should incorporate lactation support into their daily care to ensure that infants receive human milk through discharge and to help mothers achieve their personal breastfeeding goals. Nurses must possess evidence-based knowledge regarding the science of human milk, lactation, and breastfeeding. -

EAMC Lactation Consultants

BABIES WERE BORN TO BREASTFEED! Lactation Breastfeeding strengthens our children, our communities and our future. Breastfeeding also Services helps both mom and baby avoid many health problems. At East Alabama Breastfeeding is one of the most natural and Medical Center beneficial activities for mom and baby. There is no other SINGLE action by which mom can so dramatically impact the present and future health of her baby. BREASTFEEDING IS BEST! No formula can duplicate the unique properties of breastmilk, no matter how many vitamins, minerals and supplements are added to what is basically a chemical formulation. Breastmilk is the one and only natural, complete and complex food for infants. Just as importantly, breastfeeding promotes an East Alabama exceptional bond between mom and baby that ONLY mom can provide. Medical Center Lactation Center The American Academy of Pediatrics has stated Phone (334) 528-3709 that human milk is the preferred feeding for ALL infants, including premature and sick newborns, [email protected] with rare exceptions. In addition, they state that babies should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months and ideally, breastfeeding should continue for the first 12 months of life. BETTER BREASTFED BABIES WHO WE ARE RETAIL PRODUCTS OUR SERVICES Cheryl Adams BSN, RN, ICCE, IBCLC The Lactation Center at East Alabama Medical In-patient Breastfeeding Support We will visit Cheryl is an experienced maternal child nurse Center carries a growing list of Retail you every day in your room to help you and your with over 25 years experience in all areas of Breastfeeding Products. We carry Medela baby off to a good start.