Allergic Proctocolitis in the Exclusively Breastfed Infant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

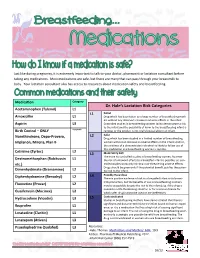

Dr. Hale's Lactation Risk Categories

Just like during pregnancy, it is extremely important to talk to your doctor, pharmacist or lactation consultant before taking any medications. Most medications are safe, but there are many that can pass through your breastmilk to baby. Your lactation consultant also has access to resources about medication safety and breastfeeding. Medication Category Dr. Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories Acetaminophen (Tylenol) L1 L1 Safest Amoxicillin L1 Drug which has been taken by a large number of breastfeeding moth- ers without any observed increase in adverse effects in the infant. Aspirin L3 Controlled studies in breastfeeding women fail to demonstrate a risk to the infant and the possibility of harm to the breastfeeding infant is Birth Control – ONLY Acceptable remote; or the product is not orally bioavailable in an infant. L2 Safer Norethindrone, Depo-Provera, Drug which has been studied in a limited number of breastfeeding Implanon, Mirena, Plan B women without an increase in adverse effects in the infant; And/or, the evidence of a demonstrated risk which is likely to follow use of this medication in a breastfeeding woman is remote. Cetrizine (Zyrtec) L2 L3 Moderately Safe There are no controlled studies in breastfeeding women, however Dextromethorphan (Robitussin L1 the risk of untoward effects to a breastfed infant is possible; or, con- etc.) trolled studies show only minimal non-threatening adverse effects. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the poten- Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) L2 tial risk to the infant. L4 Possibly Hazardous Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) L2 There is positive evidence of risk to a breastfed infant or to breast- milk production, but the benefits of use in breastfeeding mothers Fluoxetine (Prozac) L2 may be acceptable despite the risk to the infant (e.g. -

Food Allergy Outline

Allergy Evaluation-What it all Means & Role of Allergist Sai R. Nimmagadda, M.D.. Associated Allergists and Asthma Specialists Ltd. Clinical Assistant Professor Of Pediatrics Northwestern University Chicago, Illinois Objectives of Presentation • Discuss the different options for allergy evaluation. – Skin tests – Immunocap Testing • Understand the results of Allergy testing in various allergic diseases. • Briefly Understand what an Allergist Does Common Allergic Diseases Seen in the Primary Care Office • Atopic Dermatitis/Eczema • Food Allergy • Allergic Rhinitis • Allergic Asthma • Allergic GI Diseases Factors that Influence Allergies Development and Expression Host Factors Environmental Factors . Genetic Indoor allergens - Atopy Outdoor allergens - Airway hyper Occupational sensitizers responsiveness Tobacco smoke . Gender Air Pollution . Obesity Respiratory Infections Diet © Global Initiative for Asthma Why Perform Allergy Testing? – Confirm Allergens and answer specific questions. • Am I allergic to my dog? • Do I have a milk allergy? • Have I outgrown my allergy? • Do I need medications? • Am I penicillin allergic? • Do I have a bee sting allergy Tests Performed in the Diagnostic Allergy Laboratory • Allergen-specific IgE (over 200 allergen extracts) – Pollen (weeds, grasses, trees), – Epidermal, dust mites, molds, – Foods, – Venoms, – Drugs, – Occupational allergens (e.g., natural rubber latex) • Total Serum IgE (anti-IgE; ABPA) • Multi-allergen screen for IgE antibody Diagnostic Allergy Testing Serological Confirmation of Sensitization History of RAST Testing • RAST (radioallergosorbent test) invented and marketed in 1974 • The suspected allergen is bound to an insoluble material and the patient's serum is added • If the serum contains antibodies to the allergen, those antibodies will bind to the allergen • Radiolabeled anti-human IgE antibody is added where it binds to those IgE antibodies already bound to the insoluble material • The unbound anti-human IgE antibodies are washed away. -

Breastfeeding Is Best Booklet

SOUTH DAKOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH WIC PROGRAM Benefits of Breastfeeding Getting Started Breastfeeding Solutions Collecting and Storing Breast Milk Returning to Work or School Breastfeeding Resources Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine www.bfmed.org American Academy of Pediatrics www2.aap.org/breastfeeding Parenting website through the AAP www.healthychildren.org/English/Pages/default.aspx Breastfeeding programs in other states www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/CDC_BFWorkplaceSupport.pdf Business Case for Breastfeeding www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-home-work- and-public/breastfeeding-and-going-back-work/business-case Centers for Disease Control and Prevention www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm FDA Breastpump Information www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ HomeHealthandConsumer/ConsumerProducts/BreastPumps Healthy SD Breastfeeding-Friendly Business Initiative www.healthysd.gov/breastfeeding International Lactation Consultant Association www.ilca.org/home La Leche League www.lalecheleague.org MyPlate for Pregnancy and Breastfeeding www.choosemyplate.gov/moms-pregnancy-breastfeeding South Dakota WIC Program www.sdwic.org Page 1 Breastfeeding Resources WIC Works Resource System wicworks.fns.usda.gov/breastfeeding World Health Organization www.who.int/nutrition/topics/infantfeeding United States Breastfeeding Committee - www.usbreastfeeding.org U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/ Office of Women’s Health www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding -

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' Clinical Practice

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Constipation Ian M. Paquette, M.D. • Madhulika Varma, M.D. • Charles Ternent, M.D. Genevieve Melton-Meaux, M.D. • Janice F. Rafferty, M.D. • Daniel Feingold, M.D. Scott R. Steele, M.D. he American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons for functional constipation include at least 2 of the fol- is dedicated to assuring high-quality patient care lowing symptoms during ≥25% of defecations: straining, Tby advancing the science, prevention, and manage- lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, ment of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, relying on anus. The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee is com- manual maneuvers to promote defecation, and having less posed of Society members who are chosen because they than 3 unassisted bowel movements per week.7,8 These cri- XXX have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and teria include constipation related to the 3 common sub- rectal surgery. This committee was created to lead inter- types: colonic inertia or slow transit constipation, normal national efforts in defining quality care for conditions re- transit constipation, and pelvic floor or defecation dys- lated to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied function. However, in reality, many patients demonstrate by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the symptoms attributable to more than 1 constipation sub- best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive and type and to constipation-predominant IBS, as well. The not prescriptive. -

The Onset of Clinical Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients

AG-2018-65 ORIGINAL ARTICLE dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0004-2803.201800000-73 The onset of clinical manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease patients Viviane Gomes NÓBREGA1, Isaac Neri de Novais SILVA1, Beatriz Silva BRITO1, Juliana SILVA1, Maria Carolina Martins da SILVA1 and Genoile Oliveira SANTANA2,3 Received 29/10/2017 Accepted 10/8/2018 ABSTRACT – Background – The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is often delayed because of the lack of an ability to recognize its major clinical manifestations. Objective – Our study aimed to describe the onset of clinical manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Methods – A cross-sec- tional study. Investigators obtained data from interviews and the medical records of inflammatory bowel disease patients from a reference centre located in Brazil. Results – A total of 306 patients were included. The mean time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis was 28 months for Crohn’s disease and 19 months for ulcerative colitis. The main clinical manifestations in Crohn’s disease patients were weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and asthenia. The most relevant symptoms in ulcerative colitis patients were blood in the stool, faecal urgency, diarrhoea, mucus in the stool, weight loss, abdominal pain and asthenia. It was observed that weight loss, abdominal pain and distension, asthenia, appetite loss, anaemia, insomnia, fever, nausea, perianal disease, extraintestinal manifestation, oral thrush, vomiting and abdominal mass were more frequent in Crohn’s patients than in ulcerative colitis patients. The frequencies of urgency, faecal incontinence, faeces with mucus and blood, tenesmus and constipation were higher in ulcerative colitis patients than in Crohn’s disease patients. -

TITLE of STUDY Milk Allergy Is a Very Common Problem in Children. Milk

TITLE OF STUDY Milk Desensitization and Induction of Tolerance in Children Milk Allergy is a very common problem in children. Milk-induced symptoms effect up-to 20% of children, with detrimental effects on nutrition during critical periods of growth. Moreover, approximately 2-5% of children make IgE antibodies against cow’s milk, which are responsible for severe allergic reactions and anaphylaxis. Milk is the second most common food causing life-threatening anaphylaxis in North America and Europe, and the most common food to cause life- threatening symptoms world-wide. Due to the ubiquitous nature of dairy products in our diet, milk is extremely difficult to avoid. Treatment of milk allergy is currently based on strict avoidance, and patients must carry injectable adrenalin (e.g. Epipen). Our study will assess a novel and potentially life-changing therapy, by actively treating milk allergy with Oral Immunotherapy. This may allow patients to safely consume dairy products. Treatment with oral-immunotherapy has been piloted in the USA and Europe, but there is no current research into milk- immunotherapy in Canada, depriving our population of a potential cure for this very common problem. We propose to perform a well-defined clinical study, using proper control groups and immunological measures to properly understand the ideal patients and the safest and most efficacious methodologies. If successful, this study will clearly increase the margin of safety for children and young adults who suffer from life-threatening milk allergy. It can also increase the consumption of dairy products within this population, providing nutritional benefits including improved bone mineralization and growth. -

Gastroenterology and the Elderly

3 Gastroenterology and the Elderly Thomas W. Sheehy 3.1. Esophagus 3.1.1. Dysphagia Esophageal disorders, such as esophageal motility disorders, infections, tumors, and other diseases, are common in the elderly. In the elderly, dysphagia usually implies organic disease. There are two types: (1) pre-esophageal and (2) esophageal. Both are further subdivided into motor (neuromuscular) or structural (intrinsic and extrinsic) lesions.! 3.1.2. Pre-esophageal Dysphagia Pre-esophageal dysphagia (PED) usually implies neuromuscular disease and may be caused by pseudobular palsy, multiple sclerosis, amy trophic lateral scle rosis, Parkinson's disease, bulbar poliomyelitis, lesions of the glossopharyngeal nerve, myasthenia gravis, and muscular dystrophies. Since PED is due to inability to initiate the swallowing mechanism, food cannot escape from the oropharynx into the esophagus. Such patients usually have more difficulty swallowing liquid THOMAS W. SHEEHY • The University of Alabama in Birmingham, School of Medicine, Department of Medicine; and Medical Services, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Birming ham, Alabama 35233. 87 S. R. Gambert (ed.), Contemporary Geriatric Medicine © Plenum Publishing Corporation 1983 88 THOMAS W. SHEEHY than solids. They sputter or cough during attempts to swallow and often have nasal regurgitation or aspiration of food. 3.1.3. Dysfunction of the Cricopharyngeus Muscle In the elderly, this is one of the more common forms of PED.2 These patients have the sensation of an obstruction in their throat when they attempt to swallow. This is due to incoordination of the cricopharyngeus muscle. When this muscle fails to relax quickly enough during swallowing, food cannot pass freely into the esophagus. If the muscle relaxes promptly but closes too quickly, food is trapped as it attempts to enter the esophagus. -

Ulcerative Proctitis

Patient & Family Guide 2016 Ulcerative Proctitis www.nshealth.ca Ulcerative Proctitis What is Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the general name for diseases that cause inflammation (swelling and irritation) in the intestines (“gut”). It includes the following: • Ulcerative proctitis • Crohn’s disease • Ulcerative colitis What are your questions? Please ask. We are here to help you. 1 What is ulcerative proctitis and how is it different from ulcerative colitis? Ulcerative proctitis (UP) is a type of ulcerative colitis (UC). UC is an inflammatory disease of the colon (large intestine or large bowel). The inner lining of the colon becomes inflamed and has ulcerations (sores). The entire large bowel is involved in UC. When only the lowest part of the colon is involved (the rectum, 15 to 20 cm from the anus), it is called ulcerative proctitis. 15-20 cm Rectum Large intestine (large bowel) 2 How is ulcerative proctitis diagnosed? • A test called a sigmoidoscopy will tell us if you have this problem. The doctor uses a special tube which bends and has a small light and camera on the end to look at the inside of your lower bowel and rectum. The tube is passed through the anus to the rectum and into the last 25 cm of the large bowel. • A biopsy (small piece of bowel tissue is taken) during the test and sent to the lab for study. • Most people do not find the test and biopsy uncomfortable and medicine to relax or make you sleepy is not usually needed. What are the symptoms of ulcerative proctitis? • Rectal bleeding and itching, passing mucus through the rectum, and feeling like you always need to pass stool (poop) even though your bowel is empty. -

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults NAMIRAH JAMSHED, MD; ZONE-EN LEE, MD; and KEVIN W

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults NAMIRAH JAMSHED, MD; ZONE-EN LEE, MD; and KEVIN W. OLDEN, MD Washington Hospital Center, Washington, District of Columbia Constipation is traditionally defined as three or fewer bowel movements per week. Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age, inactivity, low caloric intake, low-fiber diet, low income, low educational level, and taking a large number of medications. Chronic constipa- tion is classified as functional (primary) or secondary. Functional constipation can be divided into normal transit, slow transit, or outlet constipation. Possible causes of secondary chronic constipation include medication use, as well as medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism or irritable bowel syndrome. Frail older patients may present with nonspecific symptoms of constipation, such as delirium, anorexia, and functional decline. The evaluation of constipa- tion includes a history and physical examination to rule out alarm signs and symptoms. These include evidence of bleeding, unintended weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, acute onset constipation in older patients, and rectal prolapse. Patients with one or more alarm signs or symptoms require prompt evaluation. Referral to a subspecialist for additional evaluation and diagnostic testing may be warranted. (Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):299-306. Copyright © 2011 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ▲ Patient information: onstipation is one of the most of 1,028 young adults, 52 percent defined A patient education common chronic gastrointes- constipation as straining, 44 percent as hard handout on constipation is 1,2 available at http://family tinal disorders in adults. In a stools, 32 percent as infrequent stools, and doctor.org/037.xml. -

Clinical Update and Treatment of Lactation Insufficiency

Review Article Maternal Health CLINICAL UPDATE AND TREATMENT OF LACTATION INSUFFICIENCY ARSHIYA SULTANA* KHALEEQ UR RAHMAN** MANJULA S MS*** SUMMARY: Lactation is beneficial to mother’s health as well as provides specific nourishments, growth, and development to the baby. Hence, it is a nature’s precious gift for the infant; however, lactation insufficiency is one of the explanations mentioned most often by women throughout the world for the early discontinuation of breast- feeding and/or for the introduction of supplementary bottles. Globally, lactation insufficiency is a public health concern, as the use of breast milk substitutes increases the risk of morbidity and mortality among infants in developing countries, and these supplements are the most common cause of malnutrition. The incidence has been estimated to range from 23% to 63% during the first 4 months after delivery. The present article provides a literary search in English language of incidence, etiopathogensis, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and current update on treatment of lactation insufficiency from different sources such as reference books, Medline, Pubmed, other Web sites, etc. Non-breast-fed infant are 14 times more likely to die due to diarrhea, 3 times more likely to die of respiratory infection, and twice as likely to die of other infections than an exclusively breast-fed child. Therefore, lactation insufficiency should be tackled in appropriate manner. Key words : Lactation insufficiency, lactation, galactagogue, breast-feeding INTRODUCTION Breast-feeding is advised becasue human milk is The synonyms of lactation insufficiency are as follows: species-specific nourishment for the baby, produces lactational inadequacy (1), breast milk insufficiency (2), optimum growth and development, and provides substantial lactation failure (3,4), mothers milk insufficiency (MMI) (2), protection from illness. -

Ulcerative Proctitis

Ulcerative Proctitis Ulcerative proctitis is a mild form of ulcerative colitis, a ulcerative proctitis are not at any greater risk for developing chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consisting of fine colorectal cancer than those without the disease. ulcerations in the inner mucosal lining of the large intestine that do not penetrate the bowel muscle wall. In this form of colitis, Diagnosis the inflammation begins at the rectum, and spreads no more Typically, the physician makes a diagnosis of ulcerative than about 20cm (~8″) into the colon. About 25-30% of people proctitis after taking the patient’s history, doing a general diagnosed with ulcerative colitis actually have this form of the examination, and performing a standard sigmoidoscopy. A disease. sigmoidoscope is an instrument with a tiny light and camera, The cause of ulcerative proctitis is undetermined but there inserted via the anus, which allows the physician to view the is considerable research evidence to suggest that interactions bowel lining. Small biopsies taken during the sigmoidoscopy between environmental factors, intestinal flora, immune may help rule out other possible causes of rectal inflammation. dysregulation, and genetic predisposition are responsible. It is Stool cultures may also aid in the diagnosis. X-rays are not unclear why the inflammation is limited to the rectum. There is a generally required, although at times they may be necessary to slightly increased risk for those who have a family member with assess the small intestine or other parts of the colon. the condition. Although there is a range of treatments to help ease symptoms Management and induce remission, there is no cure. -

Maternal Intake of Cow's Milk During Lactation Is Associated with Lower

nutrients Article Maternal Intake of Cow’s Milk during Lactation Is Associated with Lower Prevalence of Food Allergy in Offspring Mia Stråvik 1 , Malin Barman 1,2 , Bill Hesselmar 3, Anna Sandin 4, Agnes E. Wold 5 and Ann-Sofie Sandberg 1,* 1 Department of Biology and Biological Engineering, Food and Nutrition Science, Chalmers University of Technology, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (M.B.) 2 Institute of Environmental Medicine, Unit of Metals and Health, Karolinska Institutet, 171 77 Stockholm, Sweden 3 Department of Paediatrics, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Department of Clinical Science, Pediatrics, Sunderby Research Unit, Umeå University, 901 87 Umeå, Sweden; [email protected] 5 Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute of Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 413 90 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: ann-sofi[email protected] Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 28 November 2020 Abstract: Maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation may affect the propensity of the child to develop an allergy. The aim was to assess and compare the dietary intake of pregnant and lactating women, validate it with biomarkers, and to relate these data to physician-diagnosed allergy in the offspring at 12 months of age. Maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation was assessed by repeated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires in a prospective Swedish birth cohort (n = 508). Fatty acid proportions were measured in maternal breast milk and erythrocytes. Allergy was diagnosed at 12 months of age by a pediatrician specialized in allergy.