Gambling Dynamism the Macao Miracle Gambling Dynamism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Work Stress and Problem Gambling Among Chinese Casino Employees in Macau Irene Lai Kuen Wong* and Pui Sze Lam

Wong and Lam Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health 2013, 3:7 http://www.ajgiph.com/content/3/1/7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Work stress and problem gambling among Chinese casino employees in Macau Irene Lai Kuen Wong* and Pui Sze Lam * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic The prior literature has suggested that gaming venue employees might be an at-risk University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong group for developing gambling problems. A variety of occupational stressors and workplace factors were uncovered for causing the elevated risk. However, little theory-driven research has been conducted to investigate Asian gaming venue employees’ experience of work stress and gambling behavior. Adopting the transactional theories of stress and coping, this exploratory study examined perceived job satisfaction, work stressors, stress strains, coping responses and gambling behavior among Chinese casino employees in Macau. Semi-structured interviews with fifteen casino employees (9 men and 6 women) were conducted. Many interviewees described working at casino as very stressful. Seven types of workplace stressors were identified. Most were aware of the harmful effects of work stress on their health. They experienced physical and psychological strains despite various coping strategies were employed to alleviate job stress. Many gambled after work to ‘unwind’. Using the DSM-IV criteria, one male employee could be categorized as a pathological gambler, and five men exhibited symptoms of problem gambling. In addition to job stress and male gender, other risk factors for problem gambling were also found. The study results have implication for workplace stress prevention and responsible gambling practices. -

Gambling Among the Chinese: a Comprehensive Review

Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 1152–1166 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinical Psychology Review Gambling among the Chinese: A comprehensive review Jasmine M.Y. Loo a,⁎, Namrata Raylu a,b, Tian Po S. Oei a a School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia b Drug, Alcohol, and Gambling Service, Hornsby Hospital, Hornsby, NSW 2077, Australia article info abstract Article history: Despite being a significant issue, there has been a lack of systematic reviews on gambling and problem Received 23 November 2007 gambling (PG) among the Chinese. Thus, this paper attempts to fill this theoretical gap. A literature Received in revised form 26 March 2008 search of social sciences databases (from 1840 to now) yielded 25 articles with a total sample of 12,848 Accepted 2 April 2008 Chinese community participants and 3397 clinical participants. The major findings were: (1) Social gambling is widespread among Chinese communitiesasitisapreferredformofentertainment.(2) Keywords: Prevalence estimates for PG have increased over the years and currently ranged from 2.5% to 4.0%. (3) Gambling Chinese problem gamblers consistently have difficulty admitting their issue and seeking professional Chinese help for fear of losing respect. (4) Theories, assessments, and interventions developed in the West are Ethnicity Problem gambling currently used to explain and treat PG among the Chinese. There is an urgent need for theory-based Culture interventions specifically tailored for Chinese problem gamblers. (5) Cultural differences exist in Addiction patterns of gambling when compared with Western samples; however, evidence is inconsistent. Pathological gambling Methodological considerations in this area of research are highlighted and suggestions for further Review investigation are also included. -

Lionel Leong Is Warning of a Weak Quarter on Poor

FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo TUESDAY T. 26º/ 32º Air Quality Good MOP 8.00 3372 “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” N.º 10 Sep 2019 HKD 10.00 SURVEILLANCE CAMERAS TOOK THE GOV’T CONFIRMS: PLASTIC ENROLLMENT OF LOCAL CREDIT FOR FOILING FOUR CAR CRASH STUDENTS AT MACAU’S LIARS WHO PRETENDED A PASSENGER BAGS TO BE CHARGED AT UNIVERSITIES HAS DROPPED WAS BEHIND THE WHEEL ONE PATACA EACH 30% IN THE PAST SIX YEARS P2 P3 P3 Taiwan and the Solomon Islands put on a display of friendship yesterday, pledging to deepen ties, even as rumors persist the Pacific nation is close to severing relations in favor of China. More on p11 HEADWINDSLIONEL LEONG IS WARNING OF A WEAK QUARTER ON AHEAD POOR GAMING DATA P6 AP PHOTO AP PHOTO Philippines Five people were honored yesterday as this year’s winners of the Ramon Magsaysay Awards, regarded as Asia’s version of the Nobel Prize, including a South Korean who helped fight suicide and bullying and a Thai housewife who became a human rights defender after losing her husband to violence in southern Thailand. Vietnam is at risk of a 500,000 ton shortage of the meat most of its citizens rely on for daily protein between now and the Lunar New Year in January as African swine fever ravages the nation’s hog herd, according to Ipsos Business Consulting. North Korea State media urged citizens yesterday to “fully mobilize” to rebuild after powerful Typhoon Lingling lashed the country over the weekend, with workers rebuilding electricity networks, salvaging battered crops and helping families whose homes and property were damaged. -

For Discussion on 20 March 2009 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Implementation of Measures to Address Gambling-Relat

LC Paper No. CB(2)1090/08-09(02) For discussion on 20 March 2009 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Implementation of measures to address gambling-related problems Purpose This paper gives members an update on the progress of measures implemented to address gambling-related problems. The Ping Wo Fund 2. Home Affairs Bureau (HAB) established the Ping Wo Fund (“the Fund”) in September 2003 to finance preventive and remedial measures to address gambling-related problems. The main objects of the Fund are to finance the following measures - (a) research and studies into problems and issues relating to gambling; (b) public education and other measures to prevent or alleviate problems relating to gambling; and (c) counselling, treatment and other remedial or support services for problem and pathological gamblers and those affected by them. 3. The use and application of the Fund are determined by the Secretary for Home Affairs (SHA). The Ping Wo Fund Advisory Committee (PWFAC) was set up in September 2003 to advise SHA on the management and use of the Fund. Progress of measures 4. HAB and the PWFAC have been implementing various preventive and remedial measures. Major work undertaken is highlighted in paragraphs 5 to 17 below. A. Research on gambling-related issues 5. In December 2007, we commissioned the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) to conduct an “Evaluation Study on the Impacts of Gambling Liberalization in Nearby Cities on Hong Kong People’s Participation in Gambling Activities and Development of Counselling and Treatment Services for Problem Gamblers”. 6. Through multiple means of a telephone survey, documentary analysis, interviews with members of the four counselling and treatment centres funded by the Fund (“four Centres”) and focus group discussions with users of the four Centres, the Study - (a) examined the pattern of Hong Kong people taking part in gambling activities, and the prevalence of problem and pathological gambling in Hong Kong; and (b) evaluated the effectiveness of the four Centres. -

13Eng Journal.Pdf

Glimpse Chief Editor Siu Hoi Leung Editors Che Yi Wen Choi Yuet Ki Chan Li Heng Jamil Kanwal David McAlpin Ng Sze Sze Siu Chung Fun Wong Ching Yee Wong Lap Hin Layout Designer Siu Chung Fun 1 Wai Kiu College The English Journal 2013 Content Creative Writing 1A Arminder Drama Script - No School Bullying 5-9 1A Arminder The Everlasting Robot Dog 10 1A Asid Ali If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 11 1A Lor Ka Hei If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 12 2B Lam Sin Yi Shopping Centre 13 2C Lau Tsun Him Shopping Centre 14 3A Faraz My Wonderful Trip to Macau with My Family 15 3A Fung Wing Hung My Unforgettable Trip to Hong Kong and Macau 16 3A Ho Ka Po A Joyful Trip to Hong Kong and Macau 17 3B Lee Wan Yi My Three-day Trip to Hong Kong and Macau 18 3B Wong Ying My Trip to Macau 19 4A Ip Kun Yin A Horrible Experience 20 4B Fung Ka Fai A Horrible Experience 21 4C Chan Pui Wai A Horrible Experience 22 4C Zhou Zhen Zhen A Horrible Experience 23 5B Chow Wai Hang If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 24 5B Chu Ka Chung If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 25-26 5B Fung Ho Long If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 27 5C Lam Lap Man If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 28-29 5C Liu Chi Wa If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 30-31 5C Tsang Hing Hung If I Had 7 Days Left Living in the World 32-34 6A Cheng Ngai Mui What a Wonderful Performance! 35-36 Article 4A Lam Ching Lun Movie Review 38 4A Li Lok Yan Movie Review 39 4A Liu Wan Kai Movie Review 40 4C Zhou Zhen Zhen Movie Review 41 5B Fung Ho Long Environmental Protection -

3690-2021-01-08.Pdf

FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo FRIDAY T. 7º/ 13º Air Quality Bad MOP 8.00 3690 “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” N.º 08 Jan 2021 HKD 10.00 THE MEDIA OUTLET PLATAFORMA GOVERNMENT CONSIDERS MAJOR SHAREHOLDER URGES MGM HAS TEMPORARILY SUSPENDED RESORTS TO SELL 20% OF ITS MACAU THE OPERATION OF THEIR ONLINE LAUNCHING THIRD FINANCIAL OPERATION TO CHINESE FIRMS IN LISBON NEWSROOM STIMULUS MEASURES OPEN LETTER P4 P3 P2 AP PHOTO EVA BUCHO EVA China Two former journalists were convicted of defaming a third STABLE AND journalist by publishing an account accusing him of sexual misconduct. A court in Hangzhou ruled that the evidence provided by Zou Sicong and He Qian against prominent IMPROVINGSecretary for Economy and Finance Lei Wai Nong journalist Deng Fei was “not enough to allow forecasts that Macau economy will be ‘stable and someone to firmly believe P3 without any hesitation improving’ in 2021 that what was described truly happened.” The court ordered He and Zou to pay 11,712 yuan in damages. They plan to appeal the ruling. AP PHOTO Japan has declared a state of emergency for Tokyo and three nearby areas as coronavirus cases continue to surge, hitting a daily record of 2,447 in the capital. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga issued the declaration at the government task force for the coronavirus. It kicks in today until Feb. 7, and centers around asking restaurants and bars to close at 8 p.m. and people to stay home and not mingle in crowds. -

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

1 VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau Hong Kong During the Commission’s 2015 reporting year, massive pro- democracy demonstrations (‘‘Occupy Central’’ or the ‘‘Umbrella Movement’’) took place from September through December 2014, drawing attention to ongoing tensions over Hong Kong’s debate on electoral reform and Hong Kong’s autonomy from the Chinese cen- tral government under the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ approach. The Commission observed developments raising concerns that the Chinese and Hong Kong governments may have infringed on the rights of the people of Hong Kong, including in the areas of polit- ical participation and democratic reform, press freedom, and free- dom of assembly. UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE AND AUTONOMY Hong Kong’s Basic Law guarantees freedom of speech, religion, and assembly; promises Hong Kong a ‘‘high degree of autonomy’’; and affirms the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) applies to Hong Kong.1 The Basic Law also states that its ‘‘ultimate aim’’ is the election of Hong Kong’s Chief Execu- tive (CE) ‘‘by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly rep- resentative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures’’ and of the Legislative Council (LegCo) ‘‘by universal suffrage.’’ 2 The CE is currently chosen by a 1,200-member Election Committee,3 largely consisting of members elected in functional constituencies made up of professionals, corporations, religious and social organizations, and trade and business interest groups.4 Forty LegCo members are elected directly by voters and 30 by functional constituencies.5 The electors of many functional constituencies, however, reportedly have close ties to or are supportive of the Chi- nese government.6 Despite committing in principle to allow Hong Kong voters to elect the CE by universal suffrage in 2017, the Chinese govern- ment’s framework for electoral reform 7 restricts the ability of vot- ers to nominate CE candidates for election. -

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau Findings • During the Commission’s reporting year, a number of deeply troubling developments in Hong Kong undermined the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ governance framework, which led the U.S. Secretary of State to find that Hong Kong has not main- tained a high degree of autonomy for the first time since the handover in July 1997. • On June 30, 2020, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (National Security Law), by- passing Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. To the extent that this law criminalizes secession, subversion, terrorist activities, and collusion with foreign states, this piece of legislation vio- lates Hong Kong’s Basic Law, which specifies that Hong Kong shall pass laws concerning national security. Additionally, the National Security Law raises human rights and rule of law concerns because it violates principles such as the presumption of innocence and because it contains vaguely defined criminal offenses that can be used to unduly restrict fundamental free- doms. • The Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (PRC Liaison Office) declared in April 2020 that neither it nor the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, both being State Council agencies, were subject to Article 22 of the Basic Law—a provision designed to protect Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy. The Hong Kong government had long interpreted the provision to cover the PRC Liaison Office, but it reversed itself overnight in an ap- parent attempt to conform its position to that of the central government. -

Macau Leadership Styles and Practices: Empirical Investigations on Sino-Macanese Managerial Preferences

Sander Schroevers, Jiatong Wang/ AU-HIU Journal Vol 1 No 1 (2021) 36-43 36 MACAU LEADERSHIP STYLES AND PRACTICES: EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATIONS ON SINO-MACANESE MANAGERIAL PREFERENCES Sander Schroevers1, Jiatong Wang2 Received: April 2021 Revised: June 2021 Accepted: July 2021 _______________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract This study maps the theoretical and nomological network around effective leadership styles in Macau. Since the return of the Macau peninsula to China in 1999, Europe’s oldest rear window on China has undergone significant geo-economic and social transformation. Today, nearly half of the population comprise Mainland Chinese immigrants, while around seventy percent of tourists come from the inland. In light of the central government in Beijing’s plans for the Greater Bay Area, the Belt Road Initiative and the Renminbi offshore centre in Macau, which, in turn, will increase the presence of mainland senior executives in Macau, it is of paramount importance to investigate the relationship between the prevailing leadership styles and practices in Macau and the socio-cultural leadership philosophies practiced in Mainland China. Below we discuss the implications of the substantive findings for our understanding of effective leadership practices for this Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China. Keywords: Leadership, Culture, Leadership style, Macao, Macau, China, HRM, Chinese management JEL Classification Code: F23 _________________________________________________________________________________________ e-Journal 1. Introduction The Macau peninsula is a small slice of Europe nestled in East Asia, which directly faces Hong Kong across the Pearl River estuary. With a population of a mere 650,000 and a total land mass of only thirty square km, Macau by most standards is incredibly small. -

The Perceptions of Macao Undergraduates Regarding Help Websites for Problem Gambling

The Perceptions of Macao Undergraduates Regarding Help Websites for Problem Gambling Chang Boon Patrick Lee Heng Tang Wing Han Brenda Chan Introduction Many young people are increasingly engaged in gambling (Welte et al., 2008). A survey conducted in Macao in 2013 showed that the gambling participation rate for those in the 22 to 29 age group was around 49 percent (ISCG, 2014). Another survey, also conducted in Macao, showed that 6.6 percent of students aged 12 to 22 had gambled online. Among them, 10.7 percent and 25 percent were problem and pathological gamblers respectively (Wong, 2010). When people start gambling at a young age, they are likely to persist gambling over time (Griffiths, 1995). They also have a higher likelihood of becoming problem gamblers (Winters et al., 2005). Problem gamblers tend to gamble more than they can afford and they run into debts. As a result, they often experience anxiety, poor mental health and other psychological and social problems. They may also have suicidal thoughts (Ledgerwood et al., 2005). When the young gamblers are in trouble, they may not be sure where to turn to for help as they may be fearful of confiding in their parents or elders (Kelsey, 2014). They may surf the Internet to look for help because it is a convenient place to do so and they can do it anonymously (Lee, 2011). Very little is known, however, about the types of help that are available online. There is also little research about the perceptions of young people regarding the online help organizations. Among the published research in this area, they have tended to address the Western contexts. -

Cantoneseclass101.Com Cantoneseclass101.Com

1 CantoneseClass101.com Learn Cantonese with FREE Podcasts Introduction to Cantonese Lesson 1-25 2 CantoneseClass101.com Learn Cantonese with FREE Podcasts Introduction This is Innovative Language Learning. Go to InnovativeLanguage.com/audiobooks to get the lesson notes for this course and sign up for your FREE lifetime account. This Audiobook will take you through the basics of Cantonese with Basic Bootcamp, All About and Pronunciation lessons. The 5 Basic Bootcamp lessons each center on a practical, real-life conversation. At the beginning of the lesson, we'll introduce the background of the conversation. Then, you'll hear the conversation two times: One time at natural native speed and one time with English translation. After the conversation, you'll learn carefully selected vocabulary and key grammar concepts. Next, you'll hear the conversation 1 time at natural native speed. Finally, practice what you have learned with the review track. In the review track, a native speaker will say a word or phrase from the dialogue, wait three seconds, and then give you the English translation. Say the word aloud during the pause. Halfway through the review track, the order will be reversed. The English translation will be provided first, followed by a three-second pause, and then the word or phrase from the dialogue. Repeat the words and phrases you hear in the review track aloud to practice pronunciation and reinforce what you 2 have learned. In the 15 All About lessons, you’ll learn all about Cantonese and China. Our native teachers and language experts will explain everything you need to know to get started in Cantonese, including how to understand the writing system, grammar, pronunciation, background on culture, tradition, society, and more -- all in a fun and educational format! The 5 Pronunciation lessons take you step-by-step through the most basic skill in any language: How to pronounce words and sentences like a native speaker. -

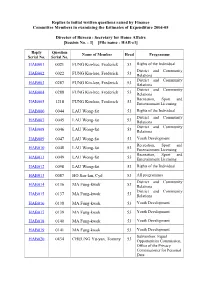

Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance Committee Members in Examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2004-05

Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2004-05 Director of Bureau : Secretary for Home Affairs [Session No. : 3] [File name : HAB-e1] Reply Question Name of Member Head Programme Serial No. Serial No. HAB001 0021 FUNG Kin-kee, Frederick 53 Rights of the Individual District and Community HAB002 0022 FUNG Kin-kee, Frederick 53 Relations District and Community HAB003 0287 FUNG Kin-kee, Frederick 53 Relations District and Community HAB004 0288 FUNG Kin-kee, Frederick 53 Relations Recreation, Sport and HAB005 1218 FUNG Kin-kee, Frederick 53 Entertainment Licensing HAB006 0044 LAU Wong-fat 53 Rights of the Individual District and Community HAB007 0045 LAU Wong-fat 53 Relations District and Community HAB008 0046 LAU Wong-fat 53 Relations HAB009 0047 LAU Wong-fat 53 Youth Development Recreation, Sport and HAB010 0048 LAU Wong-fat 53 Entertainment Licensing Recreation, Sport and HAB011 0049 LAU Wong-fat 53 Entertainment Licensing HAB012 0098 LAU Wong-fat 53 Rights of the Individual HAB013 0087 HO Sau-lan, Cyd 53 All programmes District and Community HAB014 0136 MA Fung-kwok 53 Relations District and Community HAB015 0137 MA Fung-kwok 53 Relations HAB016 0138 MA Fung-kwok 53 Youth Development HAB017 0139 MA Fung-kwok 53 Youth Development HAB018 0140 MA Fung-kwok 53 Youth Development HAB019 0141 MA Fung-kwok 53 Youth Development Subvention: Equal HAB020 0434 CHEUNG Yu-yan, Tommy 53 Opportunities Commission, Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data Reply Question Name of Member Head Programme Serial No. Serial No.