Pseudomys Novaehollandiae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

MORNINGTON PENINSULA BIODIVERSITY: SURVEY and RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Design and Editing: Linda Bester, Universal Ecology Services

MORNINGTON PENINSULA BIODIVERSITY: SURVEY AND RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Design and editing: Linda Bester, Universal Ecology Services. General review: Sarah Caulton. Project manager: Garrique Pergl, Mornington Peninsula Shire. Photographs: Matthew Dell, Linda Bester, Malcolm Legg, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI), Mornington Peninsula Shire, Russell Mawson, Bruce Fuhrer, Save Tootgarook Swamp, and Celine Yap. Maps: Mornington Peninsula Shire, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI), and Practical Ecology. Further acknowledgements: This report was produced with the assistance and input of a number of ecological consultants, state agencies and Mornington Peninsula Shire community groups. The Shire is grateful to the many people that participated in the consultations and surveys informing this report. Acknowledgement of Country: The Mornington Peninsula Shire acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as the first Australians and recognises that they have a unique relationship with the land and water. The Shire also recognises the Mornington Peninsula is home to the Boonwurrung / Bunurong, members of the Kulin Nation, who have lived here for thousands of years and who have traditional connections and responsibilities to the land on which Council meets. Data sources - This booklet summarises the results of various biodiversity reports conducted for the Mornington Peninsula Shire: • Costen, A. and South, M. (2014) Tootgarook Wetland Ecological Character Description. Mornington Peninsula Shire. • Cook, D. (2013) Flora Survey and Weed Mapping at Tootgarook Swamp Bushland Reserve. Mornington Peninsula Shire. • Dell, M.D. and Bester L.R. (2006) Management and status of Leafy Greenhood (Pterostylis cucullata) populations within Mornington Peninsula Shire. Universal Ecology Services, Victoria. • Legg, M. (2014) Vertebrate fauna assessments of seven Mornington Peninsula Shire reserves located within Tootgarook Wetland. -

Husbandry Manual for the New Holland Mouse

HUSBANDRY MANUAL FOR THE NEW HOLLAND MOUSE Pseudomys novaehollandiae . Contributors: Sonya Prosser Melbourne Zoo Mandy Lock Deakin University Kate Bodley Melbourne Zoo Jean Groat ex Melbourne Zoo Peter Myronuik ex Melbourne Zoo Peter Courtney Melbourne Zoo May 2007 CONTENTS: 1. Taxonomy 4 2. Conservation Status 4 3. Natural History 4 3.1 General Description 4 3.2 Distinguishing Features 4 3.3 Morphometrics 5 3.4 Distribution 5 3.5 Habitat 6 3.6 Wild Diet and Feeding Habits 6 3.7 Threats 7 3.8 Population Dynamics 7 3.9 Longevity 7 4. Housing Requirements 8 4.1 Indoors 8 4.1.1 Substrate 9 4.1.2 Enclosure Furnishings 9 4.1.3 Lighting 9 4.1.4 Temperature 9 4.1.5 Spatial Requirements 10 4.2 Outdoors 10 5. Handling and Transport 11 5.1 Timing of Capture and Handling 11 5.2 Catching Equipment 11 5.3 Capture and Restraint Techniques 11 5.4 Outdoors 14 5.5 Weighing and Examination 14 5.6 Release 14 5.7 Transport Requirements 14 7. Animal Health and Veterinary Care 15 7.1 Quarantine 15 7.2 Physical examination 15 7.3 Veterinary examination/procedures 15 7.4 Health Problems 16 8. Behaviour 20 9. Feeding requirements 20 9.1 Captive Diet 20 9.2 Presentation of food 21 9.3 Supplements 21 2 10. Breeding 21 10.1 Litter Size 21 10.2 Gestation 21 10.3 Sexual maturity 21 10.4 Oestrus 21 10.5 Parturition 21 10.6 Post partum oestrus 21 10.7 Weaning 21 10.8 Age at first and last breeding 21 10.9 Litter Size as a percentage of total litters 22 10.10 Birth Seasonality 22 10.11 Identification of Breeding Cycles 23 10.12 Copulation 24 10.13 Pregnancy 24 10.14 Parturition 24 10.15 Abnormal pregnancy/parturition 24 11. -

NEW HOLLAND MOUSE Pseudomys Novaehollandiae Endangered/Vulnerable

Zoos Victoria’s Fighting Extinction Species NEW HOLLAND MOUSE Pseudomys novaehollandiae Endangered/Vulnerable Photo: David Paul New Holland Mouse (NHM) populations of the endangered NHM are declining are declining rapidly in all states, with a 99% and are highly unstable due to habitat reduction in mice in Tasmania, and seven out destruction, inappropriate fire regimes and of 12 known Victorian populations now extinct. introduced predators, like cats and foxes. However, new populations of this shy native By boosting NHM numbers and the number rodent have been found in the past few years, of populations, and inspiring people to learn highlighting how little we know about the species and care about them, we can secure a bright and its range. Sadly, remaining populations future for this sweet and tiny mouse. Zoos Victoria Photo: Phoebe Burns is committed to Fighting Extinction We are focused on working with partners to secure the survival of our priority species before it is too late. With its large eyes, big rounded ears and bi-coloured pink and dusky brown tail, the New Holland Mouse is a beautiful rodent native to small areas of the heathlands, woodlands and vegetated sand dunes of south eastern Australia. Sadly, numbers of this precious mouse have declined rapidly and many populations are now extinct. Zoos Victoria is working with partners and PhD students to find the remaining populations and protect them for the future. KEY PROGRAM OBJECTIVES mammal research increased, the range of the Raise awareness and facilitate use of boot cleaning stations for $20,000 • Determine the status and population trends NHM expanded to include Victoria, south-east mitigation of Cinnamon Fungus. -

Australian Rodents Reveal Conserved Cranial Evolutionary Allometry Across 10

Manuscript Copyright The University of Chicago 2020. Preprint (not copyedited or formatted). Please use DOI when citing or quoting. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/711398 Australian rodents reveal conserved Cranial Evolutionary Allometry across 10 million years of murid evolution Ariel E. Marcy1*, Thomas Guillerme2, Emma Sherratt3, Kevin C. Rowe4,5, Matthew J. Phillips6, and Vera Weisbecker1,7 1University of Queensland, School of Biological Sciences; University of Sheffield, Department of Animal and Plant Sciences; 3University of Adelaide, School of Biological Sciences, 4Museums Victoria, Sciences Department; 5University of Melbourne, School of BioSciences; 6Queensland University of Technology, School of Biology & Environmental Science; 7Flinders University, College of Science and Engineering; *[email protected] Keywords: allometric facilitation, CREA, geometric morphometrics, molecular phylogeny, Murinae, stabilizing selection 1 Copyright The University of Chicago 2020. Preprint (not copyedited or formatted). Please use DOI when citing or quoting. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/711398 ABSTRACT Among vertebrates, placental mammals are particularly variable in the covariance between cranial shape and body size (allometry), with rodents a major exception. Australian murid rodents allow an assessment of the cause of this anomaly because they radiated on an ecologically diverse continent notably lacking other terrestrial placentals. Here we use 3D geometric morphometrics to quantify species-level and evolutionary allometries in 38 species (317 crania) from all Australian murid genera. We ask if ecological opportunity resulted in greater allometric diversity compared to other rodents, or if conserved allometry suggests intrinsic constraints and/or stabilizing selection. We also assess whether cranial shape variation follows the proposed “rule of craniofacial evolutionary allometry” (CREA), whereby larger species have relatively longer snouts and smaller braincases. -

Conservation Advice for Pseudomys Novaehollandiae (New Holland Mouse) (S266b of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999)

This conservation advice was approved by the Minister on 14 July 2010 Approved Conservation Advice for Pseudomys novaehollandiae (New Holland Mouse) (s266B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999) This Conservation Advice has been developed based on the best available information at the time this Conservation Advice was approved; this includes existing plans, records or management prescriptions for this species. Description Pseudomys novaehollandiae, Family Muridae, also known as the New Holland Mouse, is a small, burrowing native rodent. The New Holland Mouse is similar in size and appearance to the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus), although it can be distinguished by its slightly larger ears and eyes, the absence of a notch on the upper incisors and the absence of a distinctive ‘mousy’ odour. The species is grey-brown in colour and its dusky-brown tail is darker on the dorsal side. The species has a head-body length of approximately 65-90 mm, a tail length of approximately 80-105 mm and a hind foot length of approximately 20-22 mm (Menkhorst and Knight, 2001). Specimens of the New Holland Mouse from Tasmania are larger in weight than specimens from NSW and Victoria, however head-body length and skull measurements are similar between the Tasmanian and mainland forms of the species (Hocking 1980, Lazenby, 1999). Conservation Status The New Holland Mouse is listed as vulnerable. This species is eligible for listing as vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act) as the species’ geographic distribution is precarious for its survival and the estimated total number of mature individuals is limited and is likely to continue to decline (TSSC, 2009). -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Therya ISSN: 2007-3364 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste Woinarski, John C. Z.; Burbidge, Andrew A.; Harrison, Peter L. A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals Therya, vol. 6, no. 1, January-April, 2015, pp. 155-166 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=402336276010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative THERYA, 2015, Vol. 6 (1): 155-166 DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237, ISSN 2007-3364 Una revisión del estado de conservación de los mamíferos australianos A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals John C. Z. Woinarski1*, Andrew A. Burbidge2, and Peter L. Harrison3 1National Environmental Research Program North Australia and Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environmental Science Programme, Charles Darwin University, NT 0909. Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (JCZW) 2Western Australian Wildlife Research Centre, Department of Parks and Wildlife, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, WA 6946, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (AAB) 3Marine Ecology Research Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (PLH) *Corresponding author Introduction: This paper provides a summary of results from a recent comprehensive review of the conservation status of all Australian land and marine mammal species and subspecies. -

Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee Inquiry Into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria

LC EPC Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria Submission 449 Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria Submission from Assoc Professor Barbara Wilson, Deakin University. The extent of decline of Victoria’s biodiversity has been of great concern to Victorians over many decades, particularly with regards to significant declines due to historic vegetation clearing, pest animals and weed invasion, river and marine declines. Weeds continue to have impacts over large areas of natural ecosystems e.g. Coast wattle and Pine invasions causing decline in ecosystem health in Brown Stringybark in western Victoria and impacts on food availability for endangered Black Cockatoos. Climate change impacts in Victorian ecosystems have only recently become more obvious and pervasive. In this submission I have taken the opportunity to focus on the extent of decline of Victoria’s biodiversity in the heathy woodland ecosystems of the eastern Otway ranges, and indicate opportunities to restore the environment. Decline in Heathy woodlands - Anglesea Heath, eastern Otway Ranges, Victoria The Anglesea Heath is recognised for its biodiversity, and a Land Management Cooperative Agreement was established to protect those values (Land Conservation Council Victoria 1985; McMahon and Brighton 2002). The Anglesea Heath (7141 ha) was leased for brown coal extraction over an area of 400 ha (1961–2015) and has recently been incorporated into the Great Otway National Park. The vegetation communities comprise a diverse mosaic of predominantly eucalypt forests, woodlands and heathlands, interspersed with dense wet shrublands. The rich mammal assemblage in the area consists of 15 small to medium-sized mammal species. -

Appendix F: Fauna Survey Report, Ecobiological (2011)

Terrestrial Fauna Assessment for the Stratford Extension Project Appendix F: Fauna survey report, EcoBiological (2011) F-1 Fauna Survey Report: Stratford Coal Mine, Gloucester, New South Wales. Fauna Survey Report: Stratford Coal Mine, Gloucester, New South Wales. December 2010 Report prepared for Gloucester Coal Limited This report was prepared for the sole use of the proponents, their agents and any regulatory agencies involved in the development application approval process. It should not be otherwise referenced without permission. Prepared by: ecobiological David Paull Senior Ecologist NPWS Scientific Licence S12398 Reviewed by: Kristy Peters Senior Ecologist NPWS Scientific Licence S12398 Executive Summary ecobiological was commissioned by Gloucester Coal Pty Ltd to conduct fauna surveys at Stratford Coal Mine. The study area consists of a current mining operation and surrounding land currently owned and operated by Gloucester Coal Limited off Bucketts Way, Gloucester, NSW. Field surveys of the study area were conducted between April 2007 and March 2010. The key findings are summarised below. A total of 178 fauna species were recorded within the study area (consisting of 13 frog, 13 reptile, 121 bird and 31 mammal species). Two birds (Common Starling and Spotted Dove) and five of the mammals detected were exotic species (Rabbit, Hare, Cat, Fox and House Mouse). Eleven (11) threatened fauna species were recorded during the surveys, the Grey- crowned Babbler, Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Varied Sittella, Magpie Goose, Masked Owl, Brush-tailed Phascogale, Squirrel Glider, New Holland Mouse, Little Bentwing-bat, Eastern Bentwing-bat and the Eastern Freetail- bat. Nine listed migratory species (EPBC listed and listed under international conventions) were detected during surveys in the study area; the Cattle Egret, Australian Reed-warbler, Black-faced Monarch, Double-banded Plover, Latham’s Snipe, Fork-tailed Swift, Great Egret, Rainbow Bee-eater and the White-bellied Sea-eagle. -

On Mammalian Sperm Dimensions J

On mammalian sperm dimensions J. M. Cummins and P. F. Woodall Reproductive Biology Group, Department of Veterinary Anatomy, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland4067, Australia Summary. Data on linear sperm dimensions in mammals are presented. There is infor- mation on a total of 284 species, representing 6\m=.\2%of all species; 17\m=.\2%of all genera and 49\m=.\2%of all families have some representation, with quantitative information missing only from the orders Dermoptera, Pholidota, Sirenia and Tubulidentata. In general, sperm size is inverse to body mass (except for the Chiroptera), so that the smallest known spermatozoa are amongst those of artiodactyls and the largest are amongst those of marsupials. Most variations are due to differences in the lengths of midpiece and principal piece, with head lengths relatively uniform throughout the mammals. Introduction There is increasing interest in comparative studies of gametes both from the phylogenetic viewpoint (Afzelius, 1983) and also in the analysis of the evolution of sexual reproduction and anisogamy (Bell, 1982; Parker, 1982). This work emerged as part of a review of the relationship between sperm size and body mass in mammals (Cummins, 1983), in which lack of space precluded the inclusion of raw data. In publishing this catalogue of sperm dimensions we wish to rectify this defect, and to provide a reference point for, and stimulus to, further quantitative work while obviating the need for laborious compilation of raw data. Some aspects of the material presented previously (Cummins, 1983) have been re-analysed in the light of new data. Materials and Methods This catalogue of sperm dimensions has been built up from cited measurements, from personal observations and from communication with other scientists. -

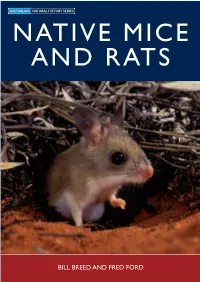

NATIVE MICE and RATS BILL BREED and FRED FORD NATIVE MICE and RATS Photos Courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman

AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD BILL BREED AND RATS MICE NATIVE NATIVE MICE AND RATS Photos courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman Australia’s native rodents are the most ecologically diverse family of Australian mammals. There are about 60 living species – all within the subfamily Murinae – representing around 25 per cent of all species of Australian mammals.They range in size from the very small delicate mouse to the highly specialised, arid-adapted hopping mouse, the large tree rat and the carnivorous water rat. Native Mice and Rats describes the evolution and ecology of this much-neglected group of animals. It details the diversity of their reproductive biology, their dietary adaptations and social behaviour. The book also includes information on rodent parasites and diseases, and concludes by outlining the changes in distribution of the various species since the arrival of Europeans as well as current conservation programs. Bill Breed is an Associate Professor at The University of Adelaide. He has focused his research on the reproductive biology of Australian native mammals, in particular native rodents and dasyurid marsupials. Recently he has extended his studies to include rodents of Asia and Africa. Fred Ford has trapped and studied native rats and mice across much of northern Australia and south-eastern New South Wales. He currently works for the CSIRO Australian National Wildlife Collection. BILL BREED AND FRED FORD NATIVE MICE AND RATS Native Mice 4thpp.indd i 15/11/07 2:22:35 PM Native Mice 4thpp.indd ii 15/11/07 2:22:36 PM AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD Native Mice 4thpp.indd iii 15/11/07 2:22:37 PM © Bill Breed and Fred Ford 2007 All rights reserved. -

Listing Advice for Pseudomys Novaehollandiae

The Minister included this species in the vulnerable category, effective from 11 August 2010 Advice to the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) on Amendment to the list of Threatened Species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 1. Name Pseudomys novaehollandiae The species is commonly known as the New Holland Mouse. It is in the Muridae family. 2. Reason for Conservation Assessment by the Committee This advice follows assessment of information provided by a public nomination to list the New Holland Mouse. The nominator suggested listing in the vulnerable category of the list. This is the Committee’s first consideration of the species under the EPBC Act. 3. Summary of Conclusion The Committee judges that the species has been demonstrated to have met sufficient elements of Criterion 2 to make it eligible for listing as vulnerable. The Committee judges that the species has been demonstrated to have met sufficient elements of Criterion 3 to make it eligible for listing as vulnerable. The highest category for which the species is eligible to be listed is vulnerable. 4. Taxonomy The species is conventionally accepted as Pseudomys novaehollandiae Waterhouse (1843) (New Holland Mouse) (Lee 1995). 5. Description The New Holland Mouse is a small, burrowing native rodent. The species is similar in size and appearance to the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus), although it can be distinguished by its slightly larger ears and eyes, the absence of a notch on the upper incisors and the absence of a distinctive ‘mousy’ odour.