Logics of Attention: Watching and Not-Watching Film and Television in Everyday Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television and the Myth of the Mediated Centre: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Television Studies?

TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? Paper presented to Media in Transition 3 conference, MIT, Boston, USA 2-4 May 2003 NICK COULDRY LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Media@lse London school of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE UK Tel +44 (0)207 955 6243 Fax +44 (0)207 955 7505 [email protected] 1 TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? ‘The celebrities of media culture are the icons of the present age, the deities of an entertainment society, in which money, looks, fame and success are the ideals and goals of the dreaming billions who inhabit Planet Earth’ Douglas Kellner, Media Spectacle (2003: viii) ‘The many watch the few. The few who are watched are the celebrities . Wherever they are from . all displayed celebrities put on display the world of celebrities . precisely the quality of being watched – by many, and in all corners of the globe. Whatever they speak about when on air, they convey the message of a total way of life. Their life, their way of life . In the Synopticon, locals watch the globals [whose] authority . is secured by their very remoteness’ Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: The Human Consequences (1998: 53-54) Introduction There seems to something like a consensus emerging in television analysis. Increasing attention is being given to what were once marginal themes: celebrity, reality television (including reality game-shows), television spectacles. Two recent books by leading media and cultural commentators have focussed, one explicitly and the other implicitly, on the consequences of the ‘supersaturation’ of social life with media images and media models (Gitlin, 2001; cf Kellner, 2003), of which celebrity, reality TV and spectacle form a taken-for-granted part. -

Cinephilia Or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Elsaesser Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment. In: Marijke de Valck, Malte Hagener (Hg.): Cinephilia. Movies, Love and Memory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2005, S. 27– 43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell 3.0 Lizenz zur Verfügung Attribution - Non Commercial 3.0 License. For more information gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment Thomas Elsaesser The Meaning and Memory of a Word It is hard to ignore that the word “cinephile” is a French coinage. Used as a noun in English, it designates someone who as easily emanates cachet as pre- tension, of the sort often associated with style items or fashion habits imported from France. As an adjective, however, “cinéphile” describes a state of mind and an emotion that, one the whole, has been seductive to a happy few while proving beneficial to film culture in general. The term “cinephilia,” finally, re- verberates with nostalgia and dedication, with longings and discrimination, and it evokes, at least to my generation, more than a passion for going to the movies, and only a little less than an entire attitude toward life. -

Marital and Familial Roles on Television: an Exploratory Sociological Analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1974 Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Charles Daniel, "Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis " (1974). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5984. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5984 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television

temp Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television A production of the Console- ing Passions book series Edited by Lynn Spigel Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Warnock and News Gothic by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Restivo, Angelo, [date] author. Title: Breaking bad and cinematic television / Angelo Restivo. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Spin offs : a production of the Console-ing Passions book series | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018033898 (print) LCCN 2018043471 (ebook) ISBN 9781478003441 (ebook) ISBN 9781478001935 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478003083 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Breaking bad (Television program : 2008–2013) | Television series— Social aspects—United States. | Television series—United States—History and criticism. | Popular culture—United States—History—21st century. Classification: LCC PN1992.77.B74 (ebook) | LCC PN1992.77.B74 R47 2019 (print) | DDC 791.45/72—dc23 LC record available at https: // lccn.loc.gov/2018033898 Cover art: Breaking Bad, episode 103 (2008). Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Georgia State University’s College of the Arts, School of Film, Media, and Theatre, and Creative Media Industries Institute, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Not to mention that most terrible drug—ourselves— which we take in solitude. —WALTER BENJAMIN Contents note to the reader ix acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 The Cinematic 25 2 The House 54 3 The Puzzle 81 4 Just Gaming 116 5 Immanence: A Life 137 notes 159 bibliography 171 index 179 Note to the Reader While this is an academic study, I have tried to write the book in such a way that it will be accessible to the generally educated reader. -

Television Content Quality and Engagement

GONZÁLEZ, M., RONCALLO-DOW, S., ARANGO-FORERO, G. Y URIBE-JONGBLOED, E. Television content quality and engagement CUADERNOS.INFO Nº 37 ISSN 0719-3661 Versión electrónica: ISSN 0719-367x http://www.cuadernos.info doi: 10.7764/cdi.37.812 Received: 08-06-2015 / Accepted: 11-04-2015 Television content quality and engagement: Analysis of a private channel in Colombia1 Calidad en contenidos televisivos y engagement: Análisis de un canal privado en Colombia Qualidade de conteúdos televisivos e engagement: Análise de um canal privado na Colômbia MANUEL IGNACIO GONZÁLEZ BERNAL2, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] SERGIO RONCALLO-DOW, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] GERMÁN ARANGO-FORERO, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] ENRIQUE URIBE-JONGBLOED, Departamento de Comunicación Social, Universidad del Norte. Barranquilla, Colombia [[email protected]] ABSTRACT RESUMEN RESUMO This paper presents the results of a Este artículo expone los resultados de Este artigo expõe os resultados de content analysis and an inquiry into un proyecto de investigación enfocado en um projeto de pesquisa enfocado em Colombian audiences regarding the comprender los elementos que intervienen compreender os elementos que intervêm concept of ‘quality television’ and its en la generación de engagement por parte na geração de engagement por parte effect upon engagement. The results de los televidentes colombianos y el aporte dos telespectadores colombianos e a show that for the sampled audience del concepto de ‘calidad televisiva’ a ese contribuição do conceito de ‘qualidade the most relevant elements in terms of proceso. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

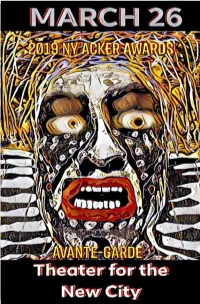

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Everything Useful I Know About Real Life I Know from Movies. Through An

Young adult fiction www.peachtree-online.com Everything useful I know about real ISBN 978-1-56145-742-7 $ life I know from movies. Through an 16.95 intense study of the characters who live and those that die gruesomely in final Sam Kinnison is a geek, and he’s totally fine scenes, I have narrowed down three basic with that. He has his horror movies, approaches to dealing with the world: his nerdy friends, and World of Warcraft. Until Princess Leia turns up in his 1. Keep your head down and your face out bedroom, worry about girls he will not. of anyone’s line of fire. studied cinema and Then Sam meets Camilla. She’s beautiful, MELISSA KEIL 2. Charge headfirst into the fray and friendly, and completely irrelevant to anthropology and has spent time as hope the enemy is too confused to his life. Sam is determined to ignore her, a high school teacher, Middle-Eastern aim straight. except that Camilla has a life of her own— tour guide, waitress, and IT help-desk and she’s decided that he’s going to be a person. She now works as a children’s 3. Cry and hide in the toilets. part of it. book editor, and spends her free time watching YouTube and geek TV. She lives Sam believes that everything he needs to in Australia. know he can learn from the movies…but “Sly, hilarious, and romantic. www.melissakeil.com now it looks like he’s been watching the A love story for weirdos wrong ones. -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

Theoretical Overviews

The Development of Television Studies PART ONE Theoretical Overviews 13 CTTC01 13 03/15/2005, 10:30 AM Horace Newcomb 14 CTTC01 14 03/15/2005, 10:30 AM The Development of Television Studies CHAPTER ONE The Development of Television Studies Horace Newcomb Since the 1990s “Television Studies” has become a frequently applied term in academic settings. In departments devoted to examination of both media, it parallels “Film Studies.” In more broadly dispersed departments of “Communi- cation Studies,” it supplements approaches to television variously described as “social science” or “quantitative” or “mass communication.” The term has be- come useful in identifying the work of scholars who participate in meetings of professional associations such as the recently renamed Society for Cinema and Media Studies as well as groups such as the National Communication Associa- tion (formerly the Speech Communication Association), the International Com- munication Association, the Broadcast Education Association, and the International Association of Media and Communication Research. These broad-based organ- izations have long regularly provided sites for the discussion of television and in some cases provided pages in sponsored scholarly journals for the publication of research related to the medium. In 2000, the Journal of Television and New Media Studies, the first scholarly journal to approximate the “television studies” desig- nation, was launched. Seen from these perspectives, “Television Studies” is useful primarily in an institutional sense. It can mark a division of labor inside academic departments (though not yet among them – so far as I know, no university has yet established a “Department of Television Studies”), a random occasion for gathering like- minded individuals, a journal title or keyword, or merely the main chance for attracting more funds, more students, more equipment – almost always at least an ancillary goal of terminological innovation in academic settings. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation.