Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paleolithic Archaeology in Iran

Intl. J. Humianities (2011) Vol. 18 (2): (63-87) Paleolithic Archaeology in Iran Hamed Vahdati Nasab 1 Received:21/9/2010 Accepted:27/2/2011 Abstract Although the Iranian plateau has witnessed Paleolithic researches since the early twenty century, still little is known about the Paleolithic of Iran. There are several reasons for this situation and lack of scholarly enthusiasm on the part of Iranian archaeologists seems to be the most imperative one. Concerning the history of Paleolithic surveys and excavations conducted in Iran, three distinct phases are recognizable. First, from the beginning of the twenty century to the 1980 when numerous field missions were executed in this region all by western institutes, second phase observes a twenty years gap in the Paleolithic studies hence; only few surveys could be performed in this period, and the third phase starts with the reopening of the Iranian fields to the non-Iranian researchers, which led to the survey and excavation of handful of new Paleolithic sites. This article reviews Paleolithic researches conducted in Iran since the beginning of twenty century to the present time. Keywords: Paleolithic, Iran, Zagros, Alborz Downloaded from eijh.modares.ac.ir at 4:34 IRST on Monday September 27th 2021 1. Assistant Professor of Archaeology, Faculty of Humianities, Tarbiat Modares University. [email protected] Paleolithic Archaeology in Iran Intl. J. Humianities (2010) Vol. 18 (1) Introduction The most peculiar point about the Iranian Iran is surrounded by some of the most Paleolithic is the absence of any hominid significant Paleolithic sites in the world. To its remains with just few exceptions (e.g. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry. -

Echogéo, 45 | 2018 Geographic Expressions of Social Change in Iran 2

EchoGéo 45 | 2018 Déclinaisons géographiques du changement social en Iran Geographic expressions of social change in Iran Introduction Amin Moghadam, Mina Saïdi-Sharouz and Serge Weber Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/echogeo/17780 DOI: 10.4000/echogeo.17780 ISSN: 1963-1197 Publisher Pôle de recherche pour l'organisation et la diffusion de l'information géographique (CNRS UMR 8586) Electronic reference Amin Moghadam, Mina Saïdi-Sharouz and Serge Weber, “Geographic expressions of social change in Iran”, EchoGéo [Online], 45 | 2018, Online since 05 September 2019, connection on 11 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/echogeo/17780 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.17780 This text was automatically generated on 11 August 2021. EchoGéo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND) Geographic expressions of social change in Iran 1 Geographic expressions of social change in Iran Introduction Amin Moghadam, Mina Saïdi-Sharouz and Serge Weber 1 Publishing a thematic issue of a geography journal on Iran in the second half of the 2010s is both a fascinating endeavor and a challenge. Over the past few years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has been the focus of much attention. H. Rohani’s election for President in 2013 brought the moderates back into power after two mandates with conservative M. Ahmadinejad. The reopening of multilateral negotiations on Iran’s infamous nuclear program was interpreted as a thaw in US-Iran relations, leading up to the Geneva agreement in 2015 which arranged for a gradual lift of international economic and diplomatic sanctions against the country. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910

The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910 Melinda Cohoon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Middle East University of Washington 2017 Committee: Arbella Bet-Shlimon Ellis Goldberg Program Authorized to Offer Degree: The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2017 Melinda Cohoon University of Washington Abstract The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910 Melinda Cohoon Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Assistant Professor Arbella Bet-Shlimon Department of History By using the Political Diaries of the Persian Gulf, I elucidate the complex tribal dynamics of the Bakhtiyari and the Arab tribes of the Khuzestan province during the early twentieth century. Particularly, these tribes were by and large influenced by the oil prospecting and drilling under the D’Arcy Oil Syndicate. My research questions concern: how the Bakhtiyari and Arab tribes were impacted by the British Oil Syndicate exploration into their territory, what the tribal affiliations with Britain and the Oil Syndicate were, and how these political dynamics changed for tribes after oil was discovered at Masjid-i Suleiman. The Oil Syndicate initially received a concession from the Qajar government, but relied much more so on tribal accommodations and treaties. In addressing my research questions, I have found that there was a contention between the Bakhtiyari and the British company, and a diplomatic relationship with Sheikh Khazal of Mohammerah (or today’s Khorramshahr) and Britain. By relying on Sheikh Khazal’s diplomatic skills with the Bakhtiyari tribe, the British Oil Syndicate penetrated further into the southwest Persia, up towards Bakhtiyari territory. -

STRATEGIC REPORT / JULY 2019 Jakub Hodek , Miguel Panadero

IRAN STRATEGIC REPORT / JULY 2019 Jakub Hodek , Miguel Panadero © 2019 Jakub Hodek, Miguel Panadero Center for Global Affairs & Strategic Studies Universidad de Navarra Facultad de Derecho–Relaciones Internacionales Campus Pamplona: 31009 Pamplona Campus Madrid: Marquesado Sta. Marta 3, 28027 Madrid https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs STRATEGIC REPORT: IRAN 3 General Index Introduction 4 General analysis of the geopolitical situation in the Middle East 5 Geography of the Middle East 6 Religion and the Sunni-Shia division 8 Brief overview of the new balance of power in the Middle East 10 The Islamic Republic of Iran 11 Geography of Iran 12 Ethnic composition 13 Strategic interests, Shia crescent 15 Before and after the Islamic Revolution of 1979 16 Domestic scene in Iran 17 SWOT analysis of the Islamic Republic of Iran 20 United States of America 21 The evolution of the JCPOA and the US-Iran relations and possible scenarios 22 Chart 1. Simple scenarios on U.S. - Iran relations. Horizon 2024 27 Russia and Iran 29 China and Iran 30 Saudi Arabia 34 Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict 36 Syria 39 Chart 2. The evolution of the conflict in Syria. Horizon 2024 41 Lebanon 42 Conclusions 45 Bibliography 46 4 GLOBAL AFFAIRS, JULY 2019 G Introduction This report will provide an in-depth analysis of Iran's role in the Middle East and its impact on the regional power balance. Studying current political and economic developments will assist in the elaboration of multiple scenarios that aim to help understand the context surrounding our subject. For the purposes of offering a more accurate prognosis, this report will examine Iran's geopolitical presence and interests in the region, economic vulnerability and energy security, social and demographic aspects and internal political dynamics. -

The Poet & the Poem 1 EPITOME of the SHAHNAMA Prologue 10 IT

CONTENTS List of Illustrations xiii Preface xvii Introduction: The Poet & the Poem 1 EPITOME OF THE SHAHNAMA Prologue 10 I THE PISHDADIAN DYNASTY 11 REIGN OF GAY UM ARTH 11 REIGN OF HUSHANG 11 REIGN OF TAHMURATH 12 REIGN OF JAMSHID 13 The Splendour of jamshid 13 The Tyranny of Zahhak 13 The Coming of Faridun 15 REIGN OF FARIDUN 16 Faridun & his Three Sons 16 REIGN OF MINUCHIHR 18 Zal & Rudaba 18 Birth & Early Exploits of Rustam 20 REIGNS OF NAWDAR, ZAV & GARSHASP 21 War with Turan 21 Robinson, B.W. digitalisiert durch: The Persian Book of Kings IDS Basel Bern 2014 viii THE PERSIAN BOOK OF KINGS II THE KAYANIAN DYNASTY 23 REIGN OF KAY QUBAD 23 Rustam's Quest for Kay Qubad 23 REIGN OF KAY KA'US 24 Disaster in Mazandaran 24 Rustam's Setzen Stages 26 Wars of Kay Ka'us 30 The Flying Machine 31 Rustam's Raid 32 Rustam & Suhrab 32 The Tragedy of Siyawush 36 Birth of Kay Khusraw 40 Revenge for Siyawush 41 Finding of Kay Khusraw 41 Abdication of Kay Ka'us 43 REIGN OF KAY KHUSRAW 43 Tragedy of Farud 43 Persian Reverses 45 Second Expedition: Continuing Reverses 46 Rustam to the Rescue 47 Rustam's Overthrow of Kamus, the Khaqan, and Others 48 Successful Termination of the Campaign 50 Rustam & the Demon Akwan 51 Bizhan & Manizha 53 Battie of the Twelve Rukhs 57 Afrasiyab's Last Campaign 60 Capture & Execution of Afrasiyab 63 The Last Days of Kay Khusraw 65 REIGN OF LUHRASP 65 Gushtasp in Rum 65 REIGN OF GUSHTASP 68 The Prophet Zoroaster 68 Vicissitudes of Isfandiyar 69 Isfandiyar's Seven Stages 70 Rustam & Isfandiyar 74 Death of Rustam 76 REIGN OF -

Analysis of the Impact of Land Use Changes on Soil Erosion Intensity and Sediment Yield Using the Intero Model in the Talar Watershed of Iran

water Article Analysis of the Impact of Land Use Changes on Soil Erosion Intensity and Sediment Yield Using the IntErO Model in the Talar Watershed of Iran Maziar Mohammadi 1, Abdulvahed Khaledi Darvishan 1,* , Velibor Spalevic 2 , Branislav Dudic 3,4,* and Paolo Billi 5 1 Department of Watershed Management Engineering, Faculty of Natural Resources, Tarbiat Modares University, Noor 46417-76489, Iran; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro, 81400 Niksic, Montenegro; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Management, Comenius University in Bratislava, 82005 Bratislava, Slovakia 4 Faculty of Economics and Engineering Management, University Business Academy, 21107 Novi Sad, Serbia 5 International Platform for Dryland Research and Education, Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, Tottori 680-0001, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.K.D.); [email protected] (B.D.); Tel.: +98-9183795477 (A.K.D.) Abstract: Land use change is known as one of the main influencing factors on soil erosion and sediment production processes. The objective of the article is to study on how land use change impacts on soil erosion by using Intensity of Erosion and Outflow (IntErO) as a process-oriented Citation: Mohammadi, M.; Khaledi soil erosion model. The study has been conducted under land use changes within the period of Darvishan, A.; Spalevic, V.; Dudic, B.; 1991–2014 in the Talar watershed located in northern Iran. The GIS environment was used to prepare Billi, P. Analysis of the Impact of Land the required maps including Digital Elevation Model (DEM), geology, land use, soil, and drainage Use Changes on Soil Erosion Intensity network. -

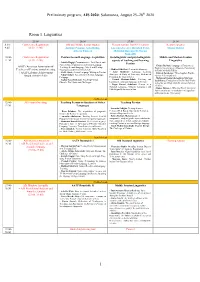

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Mohammad Reza Shah

RAHAVARD, Publishes Peer Reviewed Scholarly Articles in the field of Persian Studies: (Literature, History, Politics, Culture, Social & Economics). Submit your articles to Sholeh Shams by email: [email protected] or mail to:Rahavard 11728 Wilshire Blvd. #B607, La, CA. 90025 In 2017 EBSCO Discovery & Knowledge Services Co. providing scholars, researchers, & university libraries with credible sources of research & database, ANNOUNCED RAHAVARD A Scholarly Publication. Since then they have included articles & researches of this journal in their database available to all researchers & those interested to learn more about Iran. https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/ultimate-databases. RAHAVARD Issues 132/133 Fall 2020/Winter 2021 2853$67,163,5(6285)8785( A Quarterly Bilingual Journal of Persian Studies available (in Print & Digital) Founded by Hassan Shahbaz in Los Angeles. Shahbaz passed away on May 7th, 2006. Seventy nine issues of Rahavard, were printed during his life in diaspora. With the support & advise of Professor Ehsan Yarshater, an Advisory Commit- tee was formed & Rahavard publishing continued without interuption. INDEPENDENT: Rahavard is an independent journal entirely supported by its Subscribers dues, advertisers & contributions from its readers, & followers who constitute the elite of the Iranians living in diaspora. GOAL: To empower our young generation with the richness of their Persian Heritage, keep them informed of the accurate unbiased history of the ex- traordinary people to whom they belong, as they gain mighty wisdom from a western system that embraces them in the aftermath of the revolution & infuses them with the knowledge & ideals to inspire them. OBJECTIVE: Is to bring Rahavard to the attention & interest of the younger generation of Iranians & the global readers educated, involved & civically mobile. -

Prevalence of Tobacco Mosaic Virus in Iran and Evolutionary Analyses of the Coat Protein Gene

Plant Pathol. J. 29(3) : 260-273 (2013) http://dx.doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.OA.09.2012.0145 The Plant Pathology Journal pISSN 1598-2254 eISSN 2093-9280 © The Korean Society of Plant Pathology Open Access Prevalence of Tobacco mosaic virus in Iran and Evolutionary Analyses of the Coat Protein Gene Athar Alishiri1, Farshad Rakhshandehroo1*, Hamid-Reza Zamanizadeh1 and Peter Palukaitis2 1Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran 14515-775, Iran 2Department of Horticultural Sciences, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul 139-774, Korea (Received on September 13, 2012; Revised on February 7, 2013; Accepted on March 5, 2013) The incidence and distribution of Tobacco mosaic virus cantaloupe (Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis), courgettes (TMV) and related tobamoviruses was determined using (Cucurbita pepo L. cv. Zucchini), cucumber (Cucumis sativus an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on 1,926 sympto- L.), melon (C. melo L.), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata matic horticultural crops and 107 asymptomatic weed Duch.), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus) and samples collected from 78 highly infected fields in the winter squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch. ex Lam)], major horticultural crop-producing areas in 17 pro- eggplant (Solanum melongena L.), garlic (Allium sativum vinces throughout Iran. The results were confirmed by L.), green beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), onion (Allium host range studies and reverse transcription-polymer- ase chain reaction. The overall incidence of infection by cepa L.), pepper (Capsicum annum L.), potato (Solanum these viruses in symptomatic plants was 11.3%. The tuberosum subsp. tuberosum), spinach (Spinacia oleraceae coat protein (CP) gene sequences of a number of isolates L.) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.).