Full Article –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

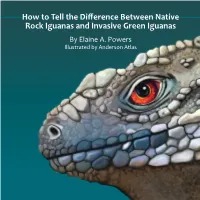

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Brongniart, 1800) in the Paris Natural History Museum

Zootaxa 4138 (2): 381–391 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4138.2.10 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:683BD945-FE55-4616-B18A-33F05B2FDD30 Rediscovery of the 220-year-old holotype of the Banded Iguana, Brachylophus fasciatus (Brongniart, 1800) in the Paris Natural History Museum IVAN INEICH1 & ROBERT N. FISHER2 1Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Sorbonne Universités, UMR 7205 (CNRS, EPHE, MNHN, UPMC; ISyEB: Institut de Systéma- tique, Évolution et Biodiversité), CP 30 (Reptiles), 25 rue Cuvier, F-75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Diego Field Station, 4165 Spruance Road, Suite 200, San Diego, CA 92101-0812, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Paris Natural History Museum herpetological collection (MNHN-RA) has seven historical specimens of Brachylo- phus spp. collected late in the 18th and early in the 19th centuries. Brachylophus fasciatus was described in 1800 by Brongniart but its type was subsequently considered as lost and never present in MNHN-RA collections. We found that 220 year old holotype among existing collections, registered without any data, and we show that it was donated to MNHN- RA from Brongniart’s private collection after his death in 1847. It was registered in the catalogue of 1851 but without any data or reference to its type status. According to the coloration (uncommon midbody saddle-like dorsal banding pattern) and morphometric data given in its original description and in the subsequent examination of the type in 1802 by Daudin and in 1805 by Brongniart we found that lost holotype in the collections. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

Suggested Guidelines for Reptiles and Amphibians Used in Outreach

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS USED IN OUTREACH PROGRAMS Compiled by Diane Barber, Fort Worth Zoo Originally posted September 2003; updated February 2008 INTRODUCTION This document has been created by the AZA Reptile and Amphibian Taxon Advisory Groups to be used as a resource to aid in the development of institutional outreach programs. Within this document are lists of species that are commonly used in reptile and amphibian outreach programs. With over 12,700 species of reptiles and amphibians in existence today, it is obvious that there are numerous combinations of species that could be safely used in outreach programs. It is not the intent of these Taxon Advisory Groups to produce an all-inclusive or restrictive list of species to be used in outreach. Rather, these lists are intended for use as a resource and are some of the more common species that have been safely used in outreach programs. A few species listed as potential outreach animals have been earmarked as controversial by TAG members for various reasons. In each case, we have made an effort to explain debatable issues, enabling staff members to make informed decisions as to whether or not each animal is appropriate for their situation and the messages they wish to convey. It is hoped that during the species selection process for outreach programs, educators, collection managers, and other zoo staff work together, using TAG Outreach Guidelines, TAG Regional Collection Plans, and Institutional Collection Plans as tools. It is well understood that space in zoos is limited and it is important that outreach animals are included in institutional collection plans and incorporated into conservation programs when feasible. -

ISG News 9(1).Indd

Iguana Specialist Group Newsletter Volume 9 • Number 1 • Summer 2006 The Iguana Specialist Group News & Comments prioritizes and facilitates conservation, science, and onservation Centers for Species Survival Formed j Cyclura spp. were awareness programs that help Cselected as a taxa of mutual concern under a new agreement between a select ensure the survival of wild group of American zoos and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The zoos - under iguanas and their habitats. the banner of Conservation Centers for Species Survival (C2S2) - and USFWS have pledged to work cooperatively to advance conservation of the selected spe- cies by identifying specific research projects, actions, and opportunities that will significantly and clearly support conservation efforts. Cyclura are the only lizards selected under the joint program. The zoos participating in the program include the San Diego Wild Animal Park, Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, The Wilds, White Oak Conservation Center and the National Zoo’s Conservation and Research Center. USFWS participation will be coordinated by Bruce Weissgold in the Division of Management Authority (bruce_weissgold @fws.gov). IN THIS ISSUE News & Comments ............... 1 RCC Facility at Fort Worth j The Fort Worth Zoo recently opened their Animal Outreach and Conservation Center (ARCC) in an off-exhibit Iguanas in the News ............... 3 A area of the zoo. The $1 million facility actually consists of three separate units. Taxon Reports ...................... 7 The primary facility houses the zoo’s outreach collection, while a state-of-the-art B. vitiensis ...................... 7 reptile conservation greenhouse will highlight the zoo’s work with endangered C. pinguis ..................... 9 iguanas and chelonians. -

CARE of the GREEN IGUANA

Client Education—Green Iguana CARE of the GREEN IGUANA Iguanas in the Wild The green or common iguana (Iguana iguana) is a tree-dwelling reptile native to the tropical and subtropical regions of central and South America and parts of Mexico. The iguana is a solitary creature. Soon after hatching, the young go off to live alone. Iguanas come together only during the breeding season. The green iguana is a strict vegetarian, feeding primarily on vines, stems, leaves and flowers. The iguana also has a good sense of sight, smell and hearing. It tends to be a wary creature and will hide or flee at the first sign of danger. During the day, iguanas bask on tree branches that hang over the water. When threatened or frightened, the iguana will drop into the water or the ground below. Keeping a Pet Iguana Unlike domestic pets that have lived with human beings for multiple generations, pet reptiles, (even those that are captive bred) are still essentially wild animals. Our goal for keeping iguanas in captivity should be to copy their natural environment and diet as closely as possible. With proper care, iguanas can live for up to 12 to 15 years and reach six feet in length. Your Iguana’s Environment Iguanas are asocial, territorial animals and should be housed singularly. Young iguanas may seem to coexist well at first, but problems soon arise since the larger, more aggressive iguana will physically intimidate its cage mates and monopolize food and heat sources. Iguanas, particularly those less than 2 years of age, should be confined to their enclosure. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

ISG Bklt 8(2)

lewisi, in a disturbed setting on Grand Cayman. 22 J. Herpetology 39(3):402-408. Goodman, R.M. and F.J. Burton. 2005. Cyclura lewisi Iguana Specialist Group Recent Literature (Grand Cayman blue iguana) hatchlings. Herpetologi- cal Review 36(2):176. Newsletter Banbury, B.L. and Y.M. Ramos. The rock iguanas of Parque Nacional Isla Cabritos. Iguana 12(4):256-261. Knapp, C.R. 2005. Working to save the Andros iguana. Volume 8 • Number 2 • Winter 2005 Iguana 12(1):9-13. Bradley, K.A. and G.P. Gerber. 2005. Conservation of the Anegada iguana (Cyclura pinguis). Iguana 12(2):79-85. Knapp, C.R. and A.K. Owens. 2005. Home range and habitat associations of a Bahamian iguana: implications Burton, F.J. 2005. Blue iguana update. Iguana for conservation. Animal Conservation 8:269-278. The Iguana Specialist Group 2005 ISG Annual Meeting 12(2):98-99. prioritizes and facilitates Lemm, J.M., S.W. Steward, and T.F. Schmidt. 2005. ISG Meeting Minutes Burton, F.J. 2005. Restoring a new wild population conservation, science, and Reproduction of the critically endangered Anegada November 6-7, 2005 of blue iguanas (Cyclura lewisi) in the Salina Reserve, awareness programs that help iguana Cyclura pinguis at San Diego Zoo. International South Andros, Bahamas Grand Cayman. Iguana 12(3):166-174. ensure the survival of wild Zoo Yearbook 39:141-152. iguanas and their habitats. Welcome and Introduction - Alberts & Hudson Durden, L.A. and C.R. Knapp. 2005. Ticks parasit- Pagni, L. and D. Ballou. 2005. Value-added conserva- Thanks were expressed to Chuck Knapp (Univ. -

TERRESTRIAL SPECIES Grand Cayman Blue Iguana Cyclura Lewisi Taxonomy and Range the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana, Cyclura Lewisi, Is

TERRESTRIAL SPECIES Grand Cayman Blue iguana Cyclura lewisi Taxonomy and Range Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Chordata, Class: Sauropsida, Order: Squamata, Family: Iguanidae Genus: Cyclura, Species: lewisi The Grand Cayman Blue iguana, Cyclura lewisi, is endemic to the island of Grand Cayman. Closest relatives are Cyclura nubila (Cuba), and Cyclura cychlura (Bahamas); all three having apparently diverged from a common ancestor some three million years ago. Status Distribution: Species endemic to Grand Cayman. Conservation: Critically endangered (IUCN Red List). In 2002 surveys indicated a wild population of 10-25 individuals. By 2005 any young being born into the unmanaged wild population were not surviving to breeding age, making the population functionally extinct. Cyclura lewisi is now the most endangered iguana on Earth. Legal: The Grand Cayman Blue iguana Cyclura lewisi is protected under the Animals Law (1976). Pending legislation, it would be protected under the National Conservation Law (Schedule I). The Department of Environment is the lead body for legal protection. The Blue Iguana Recovery Programme BIRP operates under an exemption to the Animals Law, granted to the National Trust for the Cayman Islands. Natural history While it is likely that the original population included many animals living in coastal shrubland environments, the Blue iguana now only occurs inland, in natural dry shrubland, and along the margins of dry forest. Adults are primarily terrestrial, occupying rock holes and low tree cavities. Younger individuals tend to be more arboreal. Like all Cyclura species the Blue iguana is primarily herbivorous, consuming leaves, flowers and fruits. This diet is very rarely supplemented with insect larvae, crabs, slugs, dead birds and fungi. -

Problem Solving in Reptile Practice Paul M

Topics in Medicine and Surgery Problem Solving in Reptile Practice Paul M. Gibbons, DVM, MS, Dip. ABVP (Avian), and Lisa A. Tell, DVM, Dip. ABVP (Avian), Dip. ACZM Abstract Problem-oriented reptile medicine is an explicit, definable process focused on the identification and resolution of a patient’s problems. This approach includes gathering case information, clearly defining the problems, making plans to address each prob- lem, and following up with the case over time. Case information and published literature serve as evidence to support clinical decisions and pathophysiological ratio- nale. This article describes the problem-solving process used to diagnose and treat a green iguana (Iguana iguana) that presents with ovostasis. © 2009 Published by Elsevier Inc. Key words: evidence-based veterinary medicine; follicular stasis; green iguana; Iguana iguana; preovulatory ovostasis; problem-oriented veterinary medicine roblem-oriented veterinary medicine is a logi- Objective evidence is quantitative and includes vital cal process directed toward the explicit iden- signs and the results of laboratory tests. A case sum- Ptification and resolution of a patient’s prob- mary is limited to information that is pertinent to lems. A complete, problem-oriented, veterinary the problems, but the problem-oriented, veterinary medical record includes evidence about the case, a medical record includes a complete record of all problem list, plans, and progress notes. Each prob- information related to the case. lem is described at the highest possible level of di- For purposes of illustration, the case described in agnostic refinement, and plans are developed to this article involved a 2.2-kg green iguana of unknown address each problem.