The Carriage Making Industry of Amesbury, Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAS(Driver Assistant System) ASV(Active Safety Vehicle) 2

DAS(Driver Assistant System) ASV(Active Safety Vehicle) 2 E-mail: [email protected] http://web.yonsei.ac.kr/hgjung Table of Contents • IPAS (Intelligent Parking Assist System) • APPS (Active Pedestrian Protection System) • Side Impact Solutions E-mail: [email protected] http://web.yonsei.ac.kr/hgjung IPAS: Intelligent Parking Assist System 후방 장애물 거리 경보 - 차량 후미에 장착된 초음파 센서를 이용하여 장애물 감지 - Visual, audio warning 제공 Parkmatic Parking Sensor Parking Dynamics PD1 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xlA9hmKRLSA http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EqAXUks1iOo E-mail: [email protected] http://web.yonsei.ac.kr/hgjung IPAS: Intelligent Parking Assist System 주변 장애물 거리/방향 표시 - 차량 둘레에 장착된 초음파 센서를 이용하여 장애물 감지 - 화면에 장애물 방향과 거리 표시, 음향 경보 병행 Audi Q7 Parking System BMW PDC (Parking Distance Control) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1_Y3GyCvDoU http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LGjB17udP64 E-mail: [email protected] http://web.yonsei.ac.kr/hgjung IPAS: Intelligent Parking Assist System Rear View Camera (단순 후방 카메라) 후진 기어를 넣으면, 후방 카메라 영상을 HMI로 보여줌. Rear View Camera - 2010 Mercedes-Benz Austin E-Class E350 E550 E63 AMG Sedan - Austin, TX Dealer http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EcH6dwxl81M E-mail: [email protected] http://web.yonsei.ac.kr/hgjung IPAS: Intelligent Parking Assist System 후방 카메라 + 예상 경로 표시 - 후방 카메라로 주차 상황 제공 - 조향각에 따른 예상 경로 표시 Audi Q7 Advanced Parking System http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otmL8H_zrxU E-mail: [email protected] http://web.yonsei.ac.kr/hgjung IPAS: Intelligent Parking Assist System Around View Monitor - 전후좌우에 장착된 4개의 어안렌즈 -

Overland-Cart-Catalog.Pdf

OVERLANDCARTS.COM MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES 2020 CATALOG DUMP THE WHEELBARROW DRIVE AN OVERLAND MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES PH: 877-447-2648 | GRANITEIND.COM | ARCHBOLD, OH TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Need a reason to choose Overland? We’ll give you 10. 8 & 10 cu ft Wheelbarrows ........................ 4-5 10 cu ft Wheelbarrow with Platform .............6 1. Easy to operate – So easy to use, even a child can safely operate the cart. Plus it reduces back and muscle strain. Power Dump Wheelbarrows ........................7 4 Wheel Drive Wheelbarrows ................... 8-9 2. Made in the USA – Quality you can feel. Engineered, manufactured and assembled by Granite Industries in 9 cu ft Wagon ...............................................10 Archbold, OH. 9 cu ft Wagon with Power Dump ................11 3. All electric 24v power – Zero emissions, zero fumes, Residential Carts .................................... 12-13 environmentally friendly, and virtually no noise. Utility Wagon with Metal Hopper ...............14 4. Minimal Maintenance – No oil filters, air filters, or gas to add. Just remember to plug it in. Easy Wagons ...............................................15 5. Long Battery Life – Operate the cart 6-8 hours on a single Platform Cart ................................................16 charge. 3/4 cu yd Trash Cart .....................................17 6. Brute Strength – Load the cart with up to 750 pounds on a Trailer Dolly ..................................................17 level surface. Ride On -

Public Auction

PUBLIC AUCTION Mary Sellon Estate • Location & Auction Site: 9424 Leversee Road • Janesville, Iowa 50647 Sale on July 10th, 2021 • Starts at 9:00 AM Preview All Day on July 9th, 2021 or by appointment. SELLING WITH 2 AUCTION RINGS ALL DAY , SO BRING A FRIEND! LUNCH STAND ON GROUNDS! Mary was an avid collector and antique dealer her entire adult life. She always said she collected the There are collections of toys, banks, bookends, inkwells, doorstops, many items of furniture that were odd and unusual. We started with old horse equipment when nobody else wanted it and branched out used to display other items as well as actual old wood and glass display cases both large and small. into many other things, saddles, bits, spurs, stirrups, rosettes and just about anything that ever touched This will be one of the largest offerings of US Army horse equipment this year. Look the list over and a horse. Just about every collector of antiques will hopefully find something of interest at this sale. inspect the actual offering July 9th, and July 10th before the sale. Hope to see you there! SADDLES HORSE BITS STIRRUPS (S.P.) SPURS 1. U.S. Army Pack Saddle with both 39. Australian saddle 97. U.S. civil War- severe 117. US Calvary bits All Model 136. Professor Beery double 1 P.R. - Smaller iron 19th 1 P.R. - Side saddle S.P. 1 P.R. - Scott’s safety 1 P.R. - Unusual iron spurs 1 P.R. - Brass spurs canvas panniers good condition 40. U.S. 1904- Very good condition bit- No.3- No Lip Bar No 1909 - all stamped US size rein curb bit - iron century S.P. -

Chapter Rd Roadster Division Subchapter Rd-1 General Qualifications

CHAPTER RD ROADSTER DIVISION SUBCHAPTER RD-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS RD101 Eligibility RD102 Type and Conformation RD103 Soundness and Welfare RD104 Gait Requirements SUBCHAPTER RD-2 SHOWING PROCEDURES RD105 General RD106 Appointments Classes RD107 Appointments RD108 Division of Classes SUBCHAPTER RD-3 CLASS SPECIFICATIONS RD109 General RD110 Roadster Horse to Bike RD111 Pairs RD112 Roadster Horse Under Saddle RD113 Roadster Horse to Wagon RD114 Roadster Ponies © USEF 2021 RD - 1 CHAPTER RD ROADSTER DIVISION SUBCHAPTER RD-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS RD101 Eligibility 1. Roadster Horses: In order to compete all horses must be a Standardbred or Standardbred type. Roadster Ponies are not permitted to compete in Roadster Horse classes. a. All horses competing in Federation Licensed Competitions must be properly identified and must obtain a Roadster Horse Identification number from the American Road Horse and Pony Association (ARHPA). An ARHPA Roadster Horse ID number for each horse must be entered on all entry forms for licensed competitions. b. Only one unique ARHPA Roadster Horse ID Number will be issued per horse. This unique ID number must subsequently remain with the horse throughout its career. Anyone knowingly applying for a duplicate ID Number for an individual horse may be subject to disciplinary action. c. The Federation and/or ARHPA as applicable must be notified of any change of ownership and/or competition name of the horse. Owners are requested to notify the Federation and/or ARHPA as applicable of corrections to previously submitted information, e.g., names, addresses, breed registration, pedigree, or markings. d. The ARHPA Roadster Horse ID application is available from the ARHPA or the Federation office, or it can be downloaded from the ARHPA or Federation website or completed in the competition office. -

Deer Park Winery- Good Time, Great Destination

Vol 45 Apr 14 Deer Park Winery- Good Time, Great Destination. While the leaders set a pace of about 65 mph, we held back to about 50, keeping company with Ray Brock and Walter Anderson in Ray’s ’34. It hadn’t been on the road for a while, so he didn’t want to push it. The winery property included a beautiful mix of vineyards, picnic areas, and spanish style buildings housing a world class collection of over 100 Convertibles, vintage Radios, TVs, Appliances and Auto related Neon Signs. What a show. All 26 V8ers found shady spots for an easy, pleasant old fash- ioned Sunday picnic lunch before heading home. TS Apr 13 Bus Tour is OFF- Instead we’re going to Jack Rabell’s Garage, Sat, Apr 12 San Diego Early Ford V8 Club----------------------www.sandiegoearlyfordv8club.org-----------------------Page 2 The Prez Sez. President: John Hildebrand - 760-943-1284 We had a great tour to the Deer Park V.P. Bob Symonds - 619-851-3232 winery/ museum. They have a great Secretary: Dennis Bailey - 619-954-8646 collection of convertibles. Many EFV8 club members drove their early cars Treasurer: Ken Burke - 619-469-7350 and displayed them out front in the Directors: parking lot. Folks gathered under the John Hildebrand - 760-943-1284 trees to have a nice picnic lunch and conversation. If you missed this one , Bob Symonds - 619-851-3232 make sure you join us for the next. The Dennis Bailey - 619-954-8646 El Segundo for a bus ride and tour has been cancelled Duane Ingerson - 619-426-2645 due to low early enrollment. -

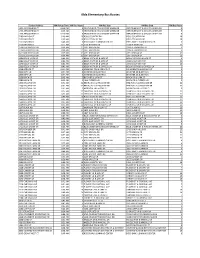

Elda Elementary Bus Routes

Elda Elementary Bus Routes Student Address AM Pickup Time AM Bus Route AM Bus Stop PM Bus Stop PM Bus Route 1399 ARROWHEAD CT 12:18 PM 6 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 1449 ARROWHEAD CT 8:45 AM 5 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 1449 ARROWHEAD CT 12:18 PM 6 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 2189 BANYON CT 8:40 AM 18 ROSS COUNTRY DAY ROSS COUNTRY DAY 18 2204 BANYON CT 8:40 AM 18 ROSS COUNTRY DAY ROSS COUNTRY DAY 18 2207 BANYON CT 8:48 AM 6 ROSS EARLY LEARNING CENTER ROSS EARLY LEARNING CENTER 6 2216 BANYON CT 8:11 AM 23 3738 HERMAN RD 3738 HERMAN RD 23 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 3 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 3 2251 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2397 BRENDA DR 21 2251 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2397 BRENDA DR 21 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 3 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 16 2270 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 2270 BELLA VISTA DR 16 2363 BELLA VISTA DR 8:43 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & CYPRESS LN BELLA VISTA DR & CYPRESS LN 3 2234 BERGER CT 12:13 PM 6 LEHMANN TRL & BERGER CT LEHMANN TRL & BERGER CT 5 2939 BETH LN 8:44 AM 6 JENNIFER DR & BETH LN JENNIFER DR & BETH LN 6 2939 BETH LN 8:44 AM 6 JENNIFER DR & BETH LN JENNIFER DR & BETH LN 6 2196 BIRCH DR 8:42 AM 3 BIRCH DR & LARK ST BIRCH DR & LARK ST 3 2283 BIRCH DR 8:43 AM 3 4016 CYPRESS LN BIRCH DR & CYPRESS -

History & STEM Fun with the Campbell County Rockpile Museum Wagons, Wagons, Wagons

History & STEM Fun with the Campbell County Rockpile Museum Wagons, Wagons, Wagons Covered wagons on Gillette Avenue - Campbell County Rockpile Museum Photo #2007.015.0036 To learn more about pioneer travels visit these links: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=4&v=GdbnriTpg_M&feature=emb_logo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fJFUYKIVKA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XmWtLrfR-Y Most wagons on the Oregon Trail were NOT Conestoga wagons. These were slow, heavy freight wagons. Most Oregon Trail pioneers used ordinary farm wagons fitted with canvas covers. The expansion of the railroad into the American West in the mid to late 1800s led to the end of travel across the nation in wagons. Are a Prairie Schooner and a Conestoga the same wagon? No. The Conestoga wagon was a much heavier wagon and often pulled by teams of up to six horses. Such wagons required reasonably good roads and were simply not practical for moving westward across the plains. The entire wagon was 26 feet long and 11 feet wide. The front wheels were 3 ½ feet high, rear wheels 4 to 4 ½ feet high. The empty wagon weighed 3000 to 3500 lbs. The Prairie schooner was the classic covered wagon that carried settlers westward across the North American plains. It was a lighter wagon designed to travel great distances on rough prairie trails. It stood 10-foot-tall, was 4 ft wide, and was 10 to 12 feet long, When the tongue and yoke were attached it was 23 feet long. The rear wheels were 50 inches in diameter and the front wheels 44 inches in diameter. -

Wagon Trains

Name: edHelper Wagon Trains When we think of the development of the United States, we can't help but think of those who traveled across the country to settle the great lands of the West. What were their travels like? What images come to your mind when you think of this great migration? The wagon train is probably one of those images. What exactly was a wagon train? It was a group of covered wagons, usually around 100 of them. These carried people and their supplies to the West before there was a transcontinental railroad. From 1837 to 1841, many people were in frustrating economic situations. Farmers, businessmen, and fur traders were looking for new opportunities. They hoped for a better climate, good crops, and better conditions. They decided to travel to the West. Missionaries wanted to convert American Indians to Christianity. They decided to head to the West. Why would these groups head out together? First of all, the amount of traveling was incredible. Much of the country they were traveling through was not settled and was difficult to travel. The trip could be confusing because of other trails made by Indians and buffalos. To get there safely, they went together. Second of all, there was a real danger that a wagon would be attacked by Native Americans. In order to have protection, it made sense to travel together. Wagon trains were very organized. People signed up to join one. There was a contract that stated the goals of the group's trip, terms to join, rules, and the details for electing officers. -

Taking Covered Wagons East a New Innovation Theory for Energy and Other Established Technology Sectors

William B. Bonvillian and Charles Weiss Taking Covered Wagons East A New Innovation Theory for Energy and Other Established Technology Sectors Frederick Jackson Turner, historian of the American frontier, argued that the always-beckoning frontier was the crucible shaping American society.1 He retold an old story, arguing that it defined our cultural landscape: when American settlers faced frustration and felt opportunities were limited, they could climb into covered wagons, push on over the next mountain chain, and open a new frontier. Even after the frontier officially closed in 1890, the nation retained more physical and social mobility than other societies. While historians debate the importance of Turner’s thesis, they still respect it. The American bent for technological advance shows a similar pattern. Typically, we find new technologies and turn them into innovations that open up new unoccupied territories—we take “covered wagon” technologies into new tech- nology frontiers. Information technology is an example. Before computing arrived, there was nothing comparable: there were no mainframes, desktops, or Internet before we embarked on this innovation wave. IT landed in a relatively open technological frontier. This has been an important capability for the U.S. growth economics has made it clear that technological and related innovation is the predominant factor driv- ing of growth.2 The ability to land in new technological open fields has enabled the U.S. economy to dominate every major Kondratiev wave of worldwide innovation William B. Bonvillian directs MIT’s Washington office and was a Senior Adviser in the U.S. Senate. He teaches innovation policy on the Adjunct Faculty at Georgetown University. -

Glencairn Early Cars

Early Motor Gars car in 1904, and w,as now being used on 26.7 .A7 . Robert McMillan of Woodlea, Moniaive, owned a motor bicycle, SM 55, which he then transferred ta a24 cwt. 16 H.P. Albion on 4.1 .06. It had a Tonneau body painted red and was registered for private use. Four years Iater, 18.3.10, it was altered to make rt into a pickup and so it was registered for Trade purposes. SM 55 was registered in the name of Thomas Moffat McMillan, Glencrosh ,7 .17.17, as a red lorry. Stanley Jackson was afi early motor car enthusiast, owning several cars when he lived at Craigle arafi, before moving to Troon (see Glencairn Gazette October 20AT. He had a 10 H.P. Argyll, SM 100, from 24.3.06 to 3.8.06 when he changed The first motor cars to be recorded by H,enry Dubs, owner of SM 7 , -\ to 16-20 H.P. Argyll of 19 cwt. Both of Dumfries County Council, in the ft,M;te-rred his cherished number to a 14 \a('<: these cars were green. Stanley Jackson Register of Motor Cars, following the H.P Daimler on 4.3.04. It had a two f also had a two-seated green Peugeot, SM introduction of the Nlotor Car Act seated Phaeton body. varnished, which 179, from 9 .7 .06 ro 18.4.07 which was 1903, were on 14 December 1903. weighed 18 cwt. Two years later in 1906 only 5 H.P. weighing 7 cwt. -

1934 Packard 1107 Convertible Sedan Owned By: James & Mary Harri Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA

Summer 2019 1934 Packard 1107 Convertible Sedan Owned by: James & Mary Harri Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA PNR CCCA & Regional Events CCCA National Events Details can be obtained by contacting the Event Manager. If no event manager is listed, contact the sponsoring organization. June 23rd - Picnic at the Dochnahls PNR Contact: Denny & Bernie Dochnahl Grand Classics® July 4th - Parade at Yarrow Pt. July 11-14, 2019. Chesapeake Bay Region PNR Contact: Al McEwan Nov 9, 2019 . SoCal Region July 21st - Forest Grove Concours September 14, 2019. Cobble Beach, Canada Contact: Oregon Region CARavans August 5th - Motoring Classic Kick-Off September 8-17 2019. .Canadian Adventure PNR Contacts: Steve Larimer & Val Dickison August 18th - Pebble Beach Concours Contact: No PNR Manager Director's Message Greetings, fellow Classic August 31st - Crescent Beach Concours enthusiast! Contact: Colin & Laurel Gurnsey Here in the Pacific Northwest, summer keeps ‘trying’ to appear, September 8th- 17th - PNR CARavan but just as soon as we make PNR Contact: McEwan's & Dickison's driving plans, the weather gods break our heart with a bit of rain. However, the season has started November 6th - Annual Meeting and we’ve had some fun. The one day event during PNR Contact: Frank Daly which we coordinated with the Horseless Carriage Club of American and had breakfast in Puyallup and December 8th - Holiday Party then journeyed to the LeMay collection at Marymount was picture perfect and a lot of fun (see story on page PNR Contact: Frank Daly 14.) If you think that you’ve ‘been to’ the LeMay family collection and you’ve been there, done that, think again. -

1928-29 Ford

cott’s Wes Auto Restying 1928-29 Coupe, Roadster, Tudor, Phaeton, and Pickup Body Repair Parts Cowl Top Panels 1928-29 Roadster, Roadster PU & Phaeton Body Parts (all except Fordor and Cabriolet) With dummy filler neck C T T2829A fiberglass 250.00 ea Smooth, no filler neck C T T2829F fiberglass 250.00 ea A - 117-A Steel 325.00 ea With working cowl vent Cowl Parts: Includes vent door, hinge, A - 114-A Front cowl sides 200.00 pr ratchet, and spring A - 1011-A RH hinge post, w/upper braces 300.00 ea C T T2829V fiberglass 650.00 ea A - 1010-A LH hinge post, w/upper braces 300.00 ea A - 1010-AB Hinge post lower braces 70.00 pr Recessed Cowl/Firewall, Fiberglass A - 1005-A Cowl upper cross bar (outer), no braces 175.00 ea (all except Fordor and Cabriolet) A - 1001-AB Cowl upper cross bar end braces 100.00 pr Laminated using fire-retardant A - 1001-ACB Cowl upper cross bar center braces 30.00 pr resin. Steel reinforcing and Door Parts floorboard supports installed. Fits Stamped Steel. Good quality, requires expert bodywork for perfect fitting. smallblock Chevy V8, even if using We recommend fitting the inner panel to body before installing outer skin. HEI distributor. Upper firewall is RH LH molded in. This is the minimum Front outer, stock A-1040-A 300.00 ea 300.00 ea recessed firewall that will allow you Front outer, smooth A-1040-AR 300.00 ea A-1041-AR 300.00 ea to keep more legroom than any Front inner A-1044-A 400.00 ea 375.00 ea other recessed firewall.