Genetic Rhabdomyolysis Within the Spectrum of the Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 Responsive to Pregabalin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Observations Letters Familial Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 Parkinsonism Presenting As Intractable Oromandibular Dystonia

Freely available online New Observations Letters Familial Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 Parkinsonism Presenting as Intractable Oromandibular Dystonia 1,2 2,3 1,3* Kyung Ah Woo , Jee-Young Lee & Beomseok Jeon 1 Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, KR, 2 Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Boramae Hospital, Seoul, KR, 3 Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, KR Keywords: Dystonia, spinocerebellar ataxia type 2, Parkinson’s disease Citation: Woo KA, Lee JY, Jeon B. Familial spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 parkinsonism presenting as intractable oromandibular dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2019; 9. doi: 10.7916/D8087PB6 * To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] Editor: Elan D. Louis, Yale University, USA Received: October 20, 2018 Accepted: December 10, 2018 Published: February 21, 2019 Copyright: ’ 2019 Woo et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution–Noncommercial–No Derivatives License, which permits the user to copy, distribute, and transmit the work provided that the original authors and source are credited; that no commercial use is made of the work; and that the work is not altered or transformed. Funding: None. Financial Disclosures: None. Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest. Ethics Statement: This study was reviewed by the authors’ institutional ethics committee and was considered exempted from further review. We have previously described a Korean family afflicted with reflex, mildly stooped posture, and parkinsonian gait. There was spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) parkinsonism in which genetic no sign of lower motor lesion, including weakness, muscle atrophy, analysis revealed CAG expansion of 40 repeats in the ATXN2 gene.1 or fasciculation. -

Cramp Fasciculation Syndrome: a Peripheral Nerve Hyperexcitability Disorder Bhojo A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS) Volume 9 | Issue 3 Article 7 7-2014 Cramp fasciculation syndrome: a peripheral nerve hyperexcitability disorder Bhojo A. Khealani Aga Khan University Hospital, Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pjns Part of the Neurology Commons Recommended Citation Khealani, Bhojo A. (2014) "Cramp fasciculation syndrome: a peripheral nerve hyperexcitability disorder," Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS): Vol. 9: Iss. 3, Article 7. Available at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pjns/vol9/iss3/7 CASE REPORT CRAMP FASCICULATION SYNDROME: A PERIPHERAL NERVE HYPEREXCITABILITY DISORDER Bhojo A. Khealani Assistant professor, Neurology section, Aga khan University, Karachi Correspondence to: Bhojo A Khealani, Department of Medicine (Neurology), Aga Khan University, Karachi. Email: [email protected] Date of submission: June 28, 2014, Date of revision: August 5, 2014, Date of acceptance:September 1, 2014 ABSTRACT Cramp fasciculation syndrome is mildest among all the peripheral nerve hyperexcitability disorders, which typically presents with cramps, body ache and fasciculations. The diagnosis is based on clinical grounds supported by electrodi- agnostic study. We report a case of young male with two months’ history of body ache, rippling, movements over calves and other body parts, and occasional cramps. His metabolic workup was suggestive of impaired fasting glucose, radio- logic work up (chest X-ray and ultrasound abdomen) was normal, and electrodiagnostic study was significant for fascicu- lation and myokymic discharges. He was started on pregablin and analgesics. To the best of our knowledge this is report first of cramp fasciculation syndrome from Pakistan. -

Cerebellar Ataxia with Neuropathy and Vestibular Areflexia Syndrome

n e u r o l o g i a i n e u r o c h i r u r g i a p o l s k a 4 8 ( 2 0 1 4 ) 3 6 8 – 3 7 2 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/pjnns Case report Cerebellar ataxia with neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS) – A case report and review of literature a a b a, Monika Figura , Małgorzata Gaweł , Anna Kolasa , Piotr Janik * a Department of Neurology, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland b 2nd Department of Clinical Radiology, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: CANVAS (cerebellar ataxia with neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome) is a rare Received 19 March 2014 neurological syndrome of unknown etiology. The main clinical features include bilateral Accepted 27 August 2014 vestibulopathy, cerebellar ataxia and sensory neuropathy. An abnormal visually enhanced Available online 6 September 2014 vestibulo-ocular reflex is the hallmark of the disease. We present a case of 58-year-old male patient who has demonstrated gait disturbance, imbalance and paresthesia of feet for 2 fl Keywords: years. On examination ataxia of gait, diminished knee and ankle re exes, absence of plantar reflexes, fasciculations of thigh muscles, gaze-evoked downbeat nystagmus and abnormal Cerebellar ataxia with neuropathy visually enhanced vestibulo-ocular reflex were found. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and vestibular areflexia syndrome revealed cerebellar atrophy. Vestibular function testing showed severely reduced horizontal Cerebellar ataxia nystagmus in response to bithermal caloric stimulation. -

Facial Myokymia: a Clinicopathological Study

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.6.745 on 1 June 1974. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1974, 37, 745-749 Facial myokymia: a clinicopathological study P. K. SETHI1, BERNARD H. SMITH, AND K. KALYANARAMAN From the Department of Neurology, Edward J. Meyer Memorial Hospital anid School of Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, N. Y., U.S.A. SYNOPSIS Clinicopathological correlations are presented in a case of facial myokymia with facial palsy. The causative lesions were considered to be metastatic tumours to the pons and it was con- cluded that both the facial palsy and the myokymia were due to interruption of supranuclear path- ways impinging on the facial nucleus. Oppenheim (1916) described a patient with con- CASE REPORT tinuous undulation and fasciculation in the right A 57 year old white man was admitted to hospital on facial muscles. The movements had started in the 30 December 1971, suffering from productive cough, infraorbital region and progressed to involve the haemoptysis, and weight loss of some months' dura- entire territory of the facial nerve. He called the tion. He had been a heavy smoker for many years. Protected by copyright. condition facial myokymia, commented on its There was no history of fever or of pains around the association with sustained facial contraction, face. and expressed the view that, like facial palsy, it He was oriented as to time, place, and person but might be an early sign of multiple sclerosis. Kino confused and lethargic and unable to describe his (1928) reported three patients with undulating symptoms well. -

Isolated Brachialis Muscle Atrophy

A Case Report & Literature Review Isolated Brachialis Muscle Atrophy John W. Karl, MD, MPH, Michael T. Krosin, MD, and Robert J. Strauch, MD or sensory complaints. His medical history was otherwise Abstract unremarkable. Physical examination revealed obvious wast- Isolated brachialis muscle atrophy, a rare entity with ing of the right brachialis muscle, most notable on the lateral few reported cases in the literature, is explained by a aspect of the distal arm (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). His biceps muscle variety of etiologies. We present a case of unilateral, was functioning with full strength and had a normal bulk. He isolated brachialis muscle atrophy that likely resulted had a normal range of active and passive motion, including from neuralgic amyotrophy. full extension and flexion of both elbows, as well as complete Figure 1. Frontal view of both arms: note the brachialis atrophy solated brachialis muscle atrophy has been rarely reported. (solid arrow) on the right side, although the biceps contracts well. Among the few cases in the literature, 1 was attributed I to a presumed compartment syndrome,1 1 to a displaced clavicle fracture,2 and 3 to neuralgic amyotrophy.3,4 We pres- ent a case of isolated brachialis muscle atrophy of unknown etiology, the presentation of which is consistent with neuralgic amyotrophy, also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome or brachial plexitis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report. AJO Case Report A 37-year-old right-handed highway worker presented for eval- uation of right-arm muscle atrophy. One year earlier, while lift- ing heavy bags at work, he felt a painful strain in his right arm, although there was no bruising or swelling. -

Abadie's Sign Abadie's Sign Is the Absence Or Diminution of Pain Sensation When Exerting Deep Pressure on the Achilles Tendo

A.qxd 9/29/05 04:02 PM Page 1 A Abadie’s Sign Abadie’s sign is the absence or diminution of pain sensation when exerting deep pressure on the Achilles tendon by squeezing. This is a frequent finding in the tabes dorsalis variant of neurosyphilis (i.e., with dorsal column disease). Cross References Argyll Robertson pupil Abdominal Paradox - see PARADOXICAL BREATHING Abdominal Reflexes Both superficial and deep abdominal reflexes are described, of which the superficial (cutaneous) reflexes are the more commonly tested in clinical practice. A wooden stick or pin is used to scratch the abdomi- nal wall, from the flank to the midline, parallel to the line of the der- matomal strips, in upper (supraumbilical), middle (umbilical), and lower (infraumbilical) areas. The maneuver is best performed at the end of expiration when the abdominal muscles are relaxed, since the reflexes may be lost with muscle tensing; to avoid this, patients should lie supine with their arms by their sides. Superficial abdominal reflexes are lost in a number of circum- stances: normal old age obesity after abdominal surgery after multiple pregnancies in acute abdominal disorders (Rosenbach’s sign). However, absence of all superficial abdominal reflexes may be of localizing value for corticospinal pathway damage (upper motor neu- rone lesions) above T6. Lesions at or below T10 lead to selective loss of the lower reflexes with the upper and middle reflexes intact, in which case Beevor’s sign may also be present. All abdominal reflexes are preserved with lesions below T12. Abdominal reflexes are said to be lost early in multiple sclerosis, but late in motor neurone disease, an observation of possible clinical use, particularly when differentiating the primary lateral sclerosis vari- ant of motor neurone disease from multiple sclerosis. -

Motor Neurone Disease

Neurology Motor neurone disease Margaret Zoing Matthew Kiernan Caring for the patient in general practice Motor neurone disease (MND) is a progressive Background neurodegenerative disease. It is characterised by motor Motor neurone disease is a neurodegenerative disease that systems failure that results in the death of nerves responsible leads to progressive disability – and eventually death – for all voluntary movements, leading to limb paralysis, within 2–3 years. weakness of the muscles of speech and swallowing, and Objective ultimately respiratory failure. Typically MND strikes patients This article describes the role of the general practitioner in at the prime of adult life, usually in the fifth to sixth decades, caring for patients with motor neurone disease. and has a short trajectory from diagnosis with an average life Discussion expectancy of less than 3 years.1 Current estimates are that The diagnosis of motor neurone disease relies on the 1400 people are living with MND in Australia at any time, presence of upper and lower motor neurone features. There with 370 newly diagnosed patients each year.2 More than one is currently no pathognomic test for motor neurone disease Australian dies every day from this most pernicious disease. and it largely remains a diagnosis of exclusion following an accurate clinical history, combined with basic screening The cause of MND remains unknown but appears heterogeneous. blood investigations and structural imaging of the brain Environmental factors may trigger an underlying susceptibility – toxins, and spinal cord. Neuro-physiological studies may be useful chemicals, metals and trauma have all been proposed.1 Most cases as an ancillary diagnostic tool. -

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene Package Intellectual Disability, Version 9.1, 31-1-2020

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Intellectual disability, version 9.1, 31-1-2020 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect DNA + SureSelect OneSeq 300kb CNV Backbone + Human All Exon V7 capture and paired-end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 10 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate and non-unique reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x A2ML1 {Otitis media, susceptibility to}, 166760 610627 66 100 100 96 AARS1 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N, 613287 601065 63 100 97 90 Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29, 616339 AASS Hyperlysinemia, -

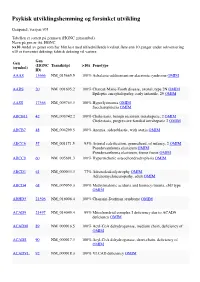

Psykisk Utviklingshemming Og Forsinket Utvikling

Psykisk utviklingshemming og forsinket utvikling Genpanel, versjon v03 Tabellen er sortert på gennavn (HGNC gensymbol) Navn på gen er iht. HGNC >x10 Andel av genet som har blitt lest med tilfredstillende kvalitet flere enn 10 ganger under sekvensering x10 er forventet dekning; faktisk dekning vil variere. Gen Gen (HGNC Transkript >10x Fenotype (symbol) ID) AAAS 13666 NM_015665.5 100% Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AARS 20 NM_001605.2 100% Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N OMIM Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29 OMIM AASS 17366 NM_005763.3 100% Hyperlysinemia OMIM Saccharopinuria OMIM ABCB11 42 NM_003742.2 100% Cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic, 2 OMIM Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 2 OMIM ABCB7 48 NM_004299.5 100% Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia OMIM ABCC6 57 NM_001171.5 93% Arterial calcification, generalized, of infancy, 2 OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, forme fruste OMIM ABCC9 60 NM_005691.3 100% Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia OMIM ABCD1 61 NM_000033.3 77% Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult OMIM ABCD4 68 NM_005050.3 100% Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type OMIM ABHD5 21396 NM_016006.4 100% Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome OMIM ACAD9 21497 NM_014049.4 99% Mitochondrial complex I deficiency due to ACAD9 deficiency OMIM ACADM 89 NM_000016.5 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADS 90 NM_000017.3 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADVL 92 NM_000018.3 100% VLCAD -

By : Ali Younes Ali Dr : Mehdi Delrobaei

K.N.Toosi University of Technology By : Ali younes ali Dr : Mehdi Delrobaei Contents 1-Introduction and general description 2-Signs and symptoms 3-Risk factors 4-Causes 5-Ways of detection 6-Treatment 7-References 1-Introduction and General description Fasciculations (muscle twitch): is a small, local, involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation which may be visible under the skin Deeper areas can be detected by electromyography (EMG) testing, though they can happen in any skeletal muscle in the body Fasciculations can often by visualized and take the form of a muscle twitch or dimpling under the skin, but usually do not generate sufficient force to move a limb Fasciculations arise as a result of spontaneous depolarization of a lower motor neuron leading to the synchronous contraction of all the skeletal muscle fibers within a single motor unit Usually, intentional movement of the involved muscle causes fasciculations to cease immediately, but they may return once the muscle is at rest again. Fasciculations have a variety of causes, the majority of which are benign, but can also be due to disease of the motor neurons They are encountered by virtually all healthy people, though for most, it is quite infrequent In some cases, the presence of fasciculations can be annoying and interfere with quality of life If a neurological examination is otherwise normal and EMG testing does not indicate any additional pathology, a diagnosis of benign fasciculation syndrome is usually made 2-Signs and symptoms The main symptom of fasciculation is focal or widespread involuntary muscle activity (twitching), which can occur at random or specific times (or places). -

Part Ii – Neurological Disorders

Part ii – Neurological Disorders CHAPTER 14 MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE Dr William P. Howlett 2012 Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania BRIC 2012 University of Bergen PO Box 7800 NO-5020 Bergen Norway NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA William Howlett Illustrations: Ellinor Moldeklev Hoff, Department of Photos and Drawings, UiB Cover: Tor Vegard Tobiassen Layout: Christian Bakke, Division of Communication, University of Bergen E JØM RKE IL T M 2 Printed by Bodoni, Bergen, Norway 4 9 1 9 6 Trykksak Copyright © 2012 William Howlett NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA is freely available to download at Bergen Open Research Archive (https://bora.uib.no) www.uib.no/cih/en/resources/neurology-in-africa ISBN 978-82-7453-085-0 Notice/Disclaimer This publication is intended to give accurate information with regard to the subject matter covered. However medical knowledge is constantly changing and information may alter. It is the responsibility of the practitioner to determine the best treatment for the patient and readers are therefore obliged to check and verify information contained within the book. This recommendation is most important with regard to drugs used, their dose, route and duration of administration, indications and contraindications and side effects. The author and the publisher waive any and all liability for damages, injury or death to persons or property incurred, directly or indirectly by this publication. CONTENTS MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE 329 PARKINSON’S DISEASE (PD) � � � � � � � � � � � -

Paraneoplastic Neurological and Muscular Syndromes

Paraneoplastic neurological and muscular syndromes Short compendium Version 4.5, April 2016 By Finn E. Somnier, M.D., D.Sc. (Med.), copyright ® Department of Autoimmunology and Biomarkers, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark 30/01/2016, Copyright, Finn E. Somnier, MD., D.S. (Med.) Table of contents PARANEOPLASTIC NEUROLOGICAL SYNDROMES .................................................... 4 DEFINITION, SPECIAL FEATURES, IMMUNE MECHANISMS ................................................................ 4 SHORT INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMUNE SYSTEM .................................................. 7 DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY ..................................................................................................... 12 THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS .................................................................................. 18 SYNDROMES OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM ................................................ 22 MORVAN’S FIBRILLARY CHOREA ................................................................................................ 22 PARANEOPLASTIC CEREBELLAR DEGENERATION (PCD) ...................................................... 24 Anti-Hu syndrome .................................................................................................................. 25 Anti-Yo syndrome ................................................................................................................... 26 Anti-CV2 / CRMP5 syndrome ............................................................................................